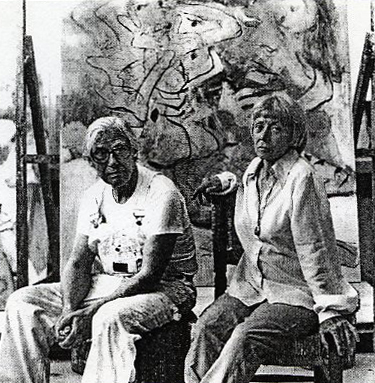

Willem and Elaine de Kooning, 1980 photo by Hans Namuth

As America prepares to celebrate its greatest living artist, the debate over his late work —and whether the artist is being well served by his court-appointed guardians—heats up.

After at least five years of ostensibly benign neglect by the art world, a dazzling array of major museum and gallery exhibitions is unfolding in the next few months to celebrate painter Willem de Kooning’s 90th birthday in April. As America’s greatest living artist is lionized at Washington. D.C:’s Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden (through January 9) with 50 paintings, drawings and sculptures spanning the years 1939 to 1985, and as the National Gallery of Art prepares for its landmark survey of 75 paintings (May 8-September 5, followed by appearances at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Tate Gallery in London), the critical debate on the quality and market potential of de Kooning’s late work, especially that from the 1980s. is sure to take center stage. And the stubborn question of whether the creative juices and conceptual powers of an acknowledged master continue to flow through old age is sure to be posed anew. Moreover, doubts about whether de Kooning has been well served in recent years by the court-appointed conservators who oversee his affairs are bound to be aired.

In an essay for the 1990 survey of de Kooning’s career at New York’s Salander-O’Reilly Galleries, critic Robert Rosenblum referred to the German word Alierstil, which he defined as the old-age style of a great and long-lived-artist.” In de Kooning’s case. that “old-age style is evocative of earlier periods, yet it also resembles the conceptual and pared-down rigor of Piet Mondrian and even Brice Marden. The surface has been scraped down, and the forms that emerge are calligraphic and linear. None of the thick, juicy, wet-into-wet layers that distinguished and literally weighed down de Kooning’s earlier work survive. As Rosenblum wrote. a “purification has taken place in which fields of luminous white waft us to an airborne realm.”

Consideration of late de Kooning rapidly raises the specter of Picasso. In another essay, Rosenblum noted that there were those who believed—falsely in his opinion—that both artists “had become artistically senile. dissolving the skeleton of their earlier works in desperate slashes of paint.” When Picasso’s late paintings were shown in Avignon in 1973, shortly after his death. they were quietly but universally hashed as the addled attempts of a spent master. Today, though, that opinion has changed considerably, both in criticism and in commerce.

There is, of course, at least one huge difference between the two great artists. Picasso maintained his intellectual faculties until the end. while de Kooning has gradually lost his brilliance through Alzheimer’s disease. In fact, de Kooning has not painted for several years, even as, aided by round-the-clock nurses, he continues to live in the glass-walled studio-home that he designed in East Hampton, Long Island. Says Robert Storr, the widely published critic and Museum of Modern Art curator (he, with Kirk Varnedoe, was instrumental in MoMA’s decision to acquire in April 1991 de Kooning’s Untitled VII from 1985), “The point at which de Kooning was no longer the final judge of his work is the point at which the debate changes its character.”

Unlike later de Koonings, works such as Woman, Sag Harbor 1964, are canonical. Nonetheless, some insist that the 80s de Koonings rank with the late Picasso and even Titian.

In that debate, the de Koonings of the ’80s have their champions as well as detractors. Although well-known collectors such as Asher B. Edelman, Graham Gund, Peter Ludwig and Leslie Wexner have acquired them, it is widely assumed that commercial rather than critical considerations have, so far, been the prime mover for the late work. A sense even prevails in some quarters that much of the market interest surrounding this work is tinged with impatience for the artist to die. “What hurts his reputation the most is the fact that he’s still around,” says one New York dealer.

“I told Elaine in 1987, ’88 that I didn’t like the late work,” says Allan Stone, the maverick Manhattan dealer, as he recalls a conversation with the artist’s wife, who died of lung cancer at the age of 70 in February 1989 “I said, ‘If you want to do him a favor, Elaine, you’ll warehouse about 80 percent of it,” recounts Stone, who also gave Elaine de Kooning legal advice after the couple separated in 1956 (they reunited in 1978) and who is perhaps the biggest private collector of Willem de Kooning’s work next to the late Joseph Hirshhorn. Elaine de Kooning had encouraged Stone to take on de Kooning when he was between dealers in the 1970s, but Stone had declined because the artist had insisted on choosing what works would be shown.

“Even in the early 1970s,” notes Stone, “only 1 out of 20 cut the mustard. His work became thinner and thinner, less and less revised. If anything, his not having had a dealer since 1987 [when dealer Xavier Fourcade] died is probably better because it makes the work scarcer.”

Nonetheless, there are those critics, collectors, curators and dealers who passionately believe de Kooning’s late work is in the same league with late Picasso, Matisse and even Titian. “Just when everyone thought de Kooning had finally done all he could do, he sort of came at it one more time with one great energetic span,” says Marla Prather, associate curator at the National Gallery and co-curator of the de Kooning show there, along with independent British curator David Sylvester and Nicholas Serota of the Tate, “I don’t want to speculate why that was—some people say it’s because of Alzheimer’s, and others say it was his studio assistants that were painting the paintings or because he was an alcoholic,” Prather continues. “My position is that it was because he was a master painter and the paintings are absolutely that. The work of the ’80s has an overarching connection back to the ’40s.”

The curatorial trio has chosen 10 paintings from 1981 through 1986, which will have a room of their own at the National Gallery. Prather says of the decision to cut off the survey at 1986, “We felt that 1986 was a strong point on which to exit, that if you went on to the next year, the work wasn’t at the same kind of high level.” Prather estimates she looked at “hundreds” of de Koonings from the ’80s. We saw everything the conservancy owned,” she says, referring to the guardianship of the now incapacitated master, who was judged incompetent to handle his own affairs in September 1989. Lisa de Kooning, the artist’s 37-year-old sole heir and only child, and John Eastman, his longtime lawyer, are co-conservators.

The lion’s share of the large body of ’80s work is strictly controlled by these co-conservators. Eastman is principally an entertainment lawyer, with clients such as Paul McCartney (his brother-in-law) and Sir Andrew Lloyd Webber. (His late father, Lee Eastman, previously represented de Kooning.) Eastman successfully defended a suit filed in the late ’60s by Sidney Janis, who was de Kooning’s dealer at the time. Janis charged that he had “exclusive agency” for the artist, and that de Kooning had sold works out of his studio for a total of $600,000. The following year, de Kooning signed up with New York’s Knoedler gallery, where Fourcade ran the contemporary department, and developed a fruitful relationship that would last for 21 years. Fourcade went out on his own in 1972, and between 1976 and 1985 de Kooning had seven solo shows at Fourcade’s East 75th Street town-house gallery. By the last show. the asking price for 1984-85 de Koonings ranged from 5300.000 to $350,000.

Commanding works such as Untitled III, 1976, predate what MOMA’s Robert Storr has called teh crucial point in the de Kooning debate, “the point at which de Kooning was no longer the final judge of his work.”

The outcome of the debate over the late work’s stature will determine, in part, just how great a fortune is ultimately at stake, given that the ballpark price for ’80s de Koonings currently hovers around the million-dollar mark, according to Madison Avenue dealer Matthew Marks. At the top end, paintings from this period have hit $2.25 million. By comparison, late Picassos have sold at auction during the last four years for approximately $210.000 to $3.3 million. Homme et femme from 1969 fetched $1.1 million at Christie’s this past May, the same threshold as an ’80s de Kooning. Even without the benefit of the 20-year reappraisal late Picasso has enjoyed, de Kooning’s late paintings are already in the seven-figure stratosphere. His Untitled XII from 1982, for example, sold to Manhattan dealer Larry Gagosian at Christie’s in May 1990 for $3.74 million, the fourth-highest price for a de Kooning at auction. (les also the only ’80s de Kooning that has been sold at Christie’s; Sotheby’s has sold only one from the period, and that was in the November 1987 Xavier Fourcade estate sale, when Untitled V fetched $385,000 just weeks after the stock market’s “Black Friday.”) Without even touching the canonical paintings, drawings, prints and sculptures from earlier periods, whose value runs into the tens of millions of dollars, the ’80s portion of the de Kooning estate—once it becomes that, and assuming the executors can successfully market it—easily tops the $100 million mark, and perhaps far more. That figure takes off again when you consider art historian and drawings expert Paul Cummings’s remark that “there are batches and batches of de Kooning drawings that no one’s ever seen.” (“De Kooning: Works on Paper,” at 57th Street’s Barbara Mathes Gallery through December, presents a major overview of the artist’s dazzling draftsmanship.)

The conservancy controls de Kooning works from all periods, although it declines to divulge any numbers. Except for a single work from the 1970s, however, so far the conservatorship has released for sale only works from the 1980s, according to Eastman. Matthew Marks is one of three New York dealers—the others are private dealer Stephen Mazoh and Pace Gallery—who privately sell 1980s works on behalf of the de Kooning conservatorship. It’s an impressive trio. Marks is just 30 years old and already has established a reputation, especially in works on paper. Well-known throughout the contemporary art world. Mazoh was the one who first approached the National Gallery in 1989, on behalf of the de Kooning conservators, to broach the idea of a de Kooning exhibition. Pace just closed its odd-couple exhibition “De Kooning and Dubuffet: The Late Works,” the gallery’s second dual showing of the artists. (None of the works came from the conservancy, however.) When de Kooning’s guardianship was studied by a court-appointed lawyer in 1989, Pace was discussed as a leading candidate to take on the job of exclusive dealer. The conservatorship bypassed that recommended route, favoring a more play-the-Field approach.

Prior to the establishment of the conservatorship, there were gallery exhibitions concentrating on de Kooning’s late work at Anthony d’Offay in London, Margo Leavin in Los Angeles and Richard Gray in Chicago, as well as at Fourcade. Gray says that in his 1987 show prices ranged from $150,000 to $350,000 for paintings from 1984-86. Since the conservatorship was set up, later work has been seen publicly, aside from the Pace shows, only at C & M Arts in New York, which mounted a show last spring of de Kooning landscape paintings from 1975-79, the period immediately preceding his big stylistic change. (None of these works was from the conservancy.) This lack of gallery showings of the late work reflects the conservatorship’s strategy of loaning pieces only to museums. The circulation of the ’80s pictures is further restricted in that their sale is limited to a high-profile group of museums and private collectors, according to Eastman, who declined to identify any of the institutions. According to Marks, the conservancy requires even private buyers of its de Kooning pictures to sign a contract promising that the work will ultimately go to a museum, thus sidestepping any possible turbulence in the secondary market.

During an exclusive interview with Art & Auction, the first he has given since the conservancy became active, Eastman sought to explain the lengthy gestation period between the establishment of the conservancy in 1989 and its initial sales 18 months later. He was addressing critics like Gray (“Everybody thought de Kooning was being badly handled at the time”) who have complained that primary market de Koonings controlled by the conservancy were scarce at the height of the art boom and that, as Eastman put it, “We didn’t know our ass from second base.” Eastman recalled, “First, we had to take care of Bill, literally clean him up, and then he had a body of work, some of it just stuffed in a warehouse on his property, and we had to bring order to that. Everything we touched was chaotic. There was no rhyme or reason to any of it. We hired Roger Anthony, who worked for the Rothko estate, and then we hired Jennifer D. Johnson as research manager. and now all of the work is in a separate ware- house under climate-controlled conditions. It has all been catalogued and photographed. That took a lot of doing.”

While Lisa de Kooning declined to participate in the interview (her lawyer said she had been hurt too many times by the press), she did speak casually with this reporter at the de Kooning conservancy’s Madison Avenue office. Wearing an understated but elegant beige dress, her gold jewelry jangling, Lisa de Kooning was all business, a far cry from old tabloid photographs of the then-troubled heiress when she was implicated in a court document (but never charged) in a Hell’s Angels drug deal on the Lower East Side in 1985. During the incompetency hearing for her father in August 1989 in Mineola, Long Island, Lisa was questioned about her spending habits and her $25,000-a-month, tax-free allowance from her. father’s assets. “I have to practice being less generous.” she told the court. In the current arrangement, she receives $13,000 a month. All papers relating to the de Kooning conservatorship are under court-ordered seal.

“Lisa is like good wine,” said Eastman in his art-filled, West 54th Street law office. “She keeps getting better. She’s Bill’s heir and decides aesthetically what pictures are going to be sold. That really is her baby.”

John A. Silberman, a partner in the powerhouse law firm of Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison, also participated in the interview with Eastman. Silberman is Lisa’s personal attorney as well as the lawyer for the de Kooning conservatorship. Silberman also represents the David Smith estates as well as Richard Serra and Brice Marden. He quickly clarified Eastman’s characterization of Lisa’s role by saying that all decisions were made with Eastman’s co-approval, a key stipulation of the guardianship’s ground rules.

There has been considerable but mostly not-for-attribution criticism of Eastman and Silberman on a number of sensitive fronts, including the issues of dealer representation and the lack of any vehicle to authenticate de Kooning works. One observer, disgusted with the dominant role being played by the two entertainment lawyers, says, “It’s all show biz to them.”

Asked if the conservancy would be setting up a de Kooning committee to determine authenticity, Eastman shot back, “You mean, like the Rembrandt committee where everything is screwed up eight different ways?” So far, no official channel for authenticating de Kooning’s exists. The de Kooning office will confirm that a record exists for a particular artwork but does not issue certificates. “We don’t make any assumptions or judgments on our own,” says Jennifer Johnson. “We’re just reporting the facts.”

“Nobody is willing to tell you anything or take a stand,” says one private collector currently involved in a suit over a disputed group of small-scale de Kooning paintings from the 1960s. “Everyone is afraid of being sued. I cannot get anything from the family, from the de Kooning office or from Sotheby’s or Christie’s. They don’t want there to be a problem.” In the absence of any other authentication vehicle, dealer provenance becomes the only reliable touchstone. This, however, causes problems in the case of the large numbers of works (mostly on paper) that de Kooning, when he had his wits about him, gave away.

Eastman insisted there’s no doubt about the authenticity of the conservatorship’s holdings at least. “The conservatorship is dealing with real vanilla ice cream here,” he said. He did, however, corroborate the widely held view that a de Kooning catalogue raisonne would be a most difficult undertaking, adding, “But there’s no reason to rush into it just because people are saying we should.”

On the issue of dealer representation, many have charged that the conservancy cloisters the de Kooning treasures like a modern-day Cerberus. “I don’t think they’re doing a very good job,” says Paul Cummings. “They think they’re doing a brilliant one, but I don’t see it. De Kooning should have major dealer representation. Even Picasso always had dealers. It’s important for the continuity of the market to have representation.” Asked in the interview why the conservatorship hasn’t chosen a solo dealer to navigate the great de Kooning ship, Eastman said, “Look, obviously Bill de Kooning is a great plum. When we started this, there was tremendous pressure from art dealers on all sides, especially to do a gallery show. It was really fierce, like circling sharks. They thought we were babes in the woods. But we decided fairly quickly that Bill should be treated like an Old Master, because he is. There has never been a great museum show of de Kooning’s work, and so the first thing that Lisa, John and I decided to do was to correct that.”

Once again, Silberman interjected to soothe Eastman’s verbal bite. “Art dealers are very much part of the process,” said Silberman. “We’ve always sought their advice.” Silberman also made it clear that paintings are “only sold through dealers.”

Undeniably, though, the spigot, both at dealers and at auction, for de Kooning’s ’80s work was shut tight at the crest of the market boom, while paintings from his classic period of the “40s. ’50s and ’60s commanded breathtaking prices. For example, Interchange. his 1955 masterpiece, fetched an impossible $20.68 million at Sotheby’s New York in November 1989. (That particular sale has its own story. Tokyo dealer and collector Shigeki Kameyama acquired Interchange at the auction but subsequently lost his client for it. He also bought Picasso’s Le miroir for the same client, paying $26.4 million the following week at the same house. His $47 million or so shortfall forced him to cut a deal with Sotheby’s and swap hundreds of lesser pictures from his inventory to meet collateral demands and pay off his whopping debt. Interchange. Art & Auction has now learned, never went to Japan and is currently in Kameyama’s New York warehouse. according to a well-informed source. The National Gallery has requested the picture for its show, but Kameyama, according to the same source, is extremely reluctant to risk lending it. “There’s no guarantee of its safe return,” says the source, who insists on anonymity. “Anything could happen, and insurance only pays for damage or restoration.” Efforts to contact Kameyama for comment were unsuccessful.)

While Eastman characterizes the conservancy’s efforts as “purposeful,” and all indicators appear to blink that way, some observers take a dimmer view of how the ’80s work has been handled in the marketplace. “The people who are pushing late de Koonings, rather than being sparing and selective. are trying to overwhelm people. That’s a big mistake,” says Allan Frumkin, the veteran 57th Street dealer. “There are opportunities for selling a dubious bill of goods. Connoisseurship, as you know, has not exactly gone up.”

The conservancy makes no bones about its commitment to the late work. “We’ve only sold ’80s pictures because, as far as we’re concerned, the thrust has been toward that decade,” said Eastman. “That will be the next museum show.” In fact, Gary Garrels, the recently appointed Elise S. Haas chief curator and curator of paintings and sculpture at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, is organizing the first museum show devoted to late de Koonings. With the tentative title “Willem de Kooning: The Late Works, 1980-1986,” the show will open at the museum in fall 1995 and travel to the Walker Art Center, the 43-year- old curator’s previous home. An East Coast venue and additional European stops for the some 40 works are likely, Asked if he is going to consider post-’86 de Koonings. Carrels says, “Of course, that’s one of the questions in doing this exhibition: what do you include in the oeuvre? That’s a question I can’t answer at this point, but I hope some will be in the show. This is an important body of work. I see in it a kind of freedom and synthesis, and breathtaking self-confidence. I know there are people out there with questions, and I’m aware of the weight of these questions.”

He’s surely not the only one.