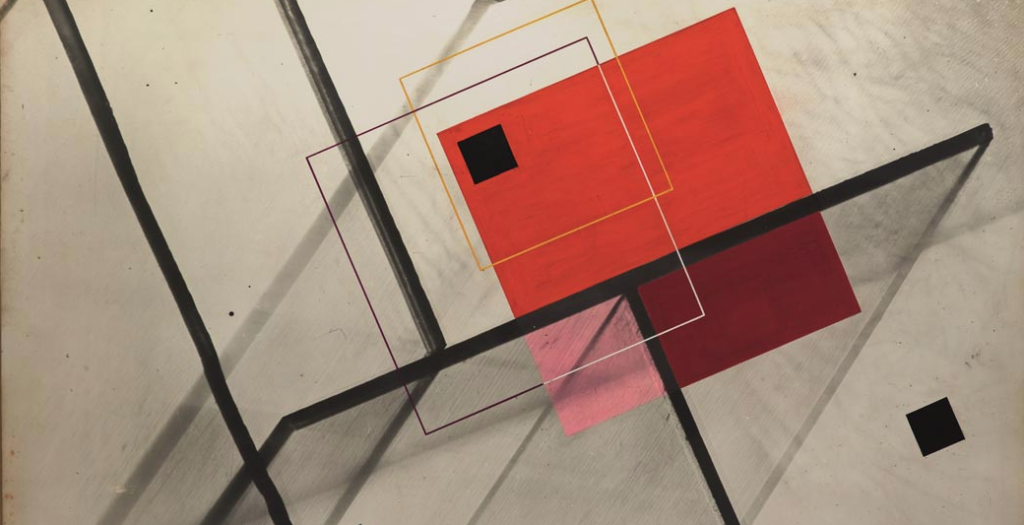

Luigi Veronesi’s “Composizione n. 53 (Composition n. 53),” 1938, currently on view at Sperone Westwater in New York

Sperone Westwater Gallery’s “Painting in Italy 1910s-1950s: Futurism, Abstraction, Concrete Art” — which is accompanied by a 392-page hard cover book that elaborately documents all that is encompassed in the show’s epic title — is an ambitious and highly unusual exhibition (through January 23).

The brainchild of co-founder and partner Gian Enzo Sperone, who set out to locate, acquire, and curate top examples of this mostly under-known and even obscure field, the show creates a discovery channel of sorts for a big chunk of 20th-century Italian art. Giacomo Balla, considered the forerunner of modern Italian art and covering the Utopian tinged Futurist period, and Lucio Fontana, the current Post-War darling of the blue chip auction trade, are the only famous names amidst the checklist of some 32 artists. It seems to be Sperone’s way of bringing attention to a corpus of Italian art, largely ignored or simply isolated from the European and American canon and presented in a grand New York setting, that of the gallery’s bespoke Norman Foster building on the Bowery.

A ravishing selection of Balla’s high velocity works, 17 in all, and largely comprised of post-card sized tempera and watercolor on paper or gouache and collage on cardboard, is alone worth the trip. At least a third of the Balla works on paper float on punch holed, unlined paper, attesting both to their fragility and staying power, with examples dating from 1912 to 1918, virtually the prime years of the Futurist movement. Others were literally postcard compositions mailed by Balla to his Futurist comrade F.T. Marinetti, providing a kind of provenance one might only dream of and posted decades before the arrival of Mail Art.

Fontana is represented by two modest examples: “Concetto Spaziale,” 1959, an ash gray hued aniline on paper laid down on canvas, and a more interesting and earlier “Studio per decorazione spaziale,” 1952, executed in pencil, watercolor, and gouache on paper. The duo, without their brand recognizable slashes or punctures, share a wall with larger abstractions by Mario Nigro (1954), Enrico Bordoni (1946), and Bruno Munari (1951). Without the wall labels you wouldn’t have a clue as to who was who, let alone a sense of market values.

Drifting through the exhibition and, at times, ignoring the comprehensive, illustrated checklist provided by the gallery, you could imagine yourself touring an equally unheralded exhibition staged by the artist-organized American Abstract Artists’ Group during the 1930s or ’40s in New York.

The exhibition is organized in part by a mini-series of one-man on one-wall shows, giving the viewer a chance to take in the robust abstraction of, say, Enrico Prampolini, especially the wood panel composition “Apparizione biologica,” 1940, in fresco, gouache, oil, and enamel, or the stunning photograms of Luigi Veronesi, 1936-38, works that would give Moholy-Nagy a run for his money.

Though decidedly male-centric in representation, the exhibition includes two first-rate abstractions by Carla Badiali, dating from 1935 and 1937/42, just enough of a sampling to inspire hope for more.

At any step, if one wanted to go deeper, the encyclopedic-like texts written by the art historian Maria Antonella Pelizzari, which provide mini-biographies and documentation of the artists exhibited, will enrich whatever understanding you might come away with.

Sperone described a kind of moral imperative that inspired him to organize the exhibition. “Every time I buy a new publication about modern art from the ’20s, ’30s, and ’40s,” said the seasoned contemporary art dealer, “I see very little of art related to my own experience.”

He went on to say, “A number of the artists I met at the very beginning of my career in Italy, they’re nowhere or forgotten and undervalued, so I thought it would be something necessary for me to do as a dealer, and as an Italian.”

It will be interesting to see if any of these under-known/undervalued Italian artists will emigrate further onto the global art stage, but suffice it to say, the visa application is on its way.