This essay was orginally published on the occasion of Richard Hunt’s 1989 solo show at Dorsky Gallery.

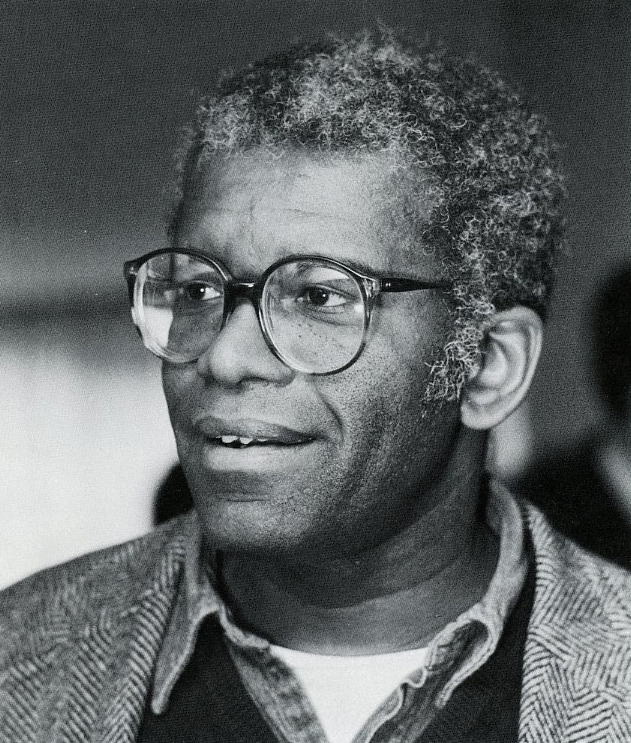

Richard Hunt, 1986 – credit: Bobbe Wolfe

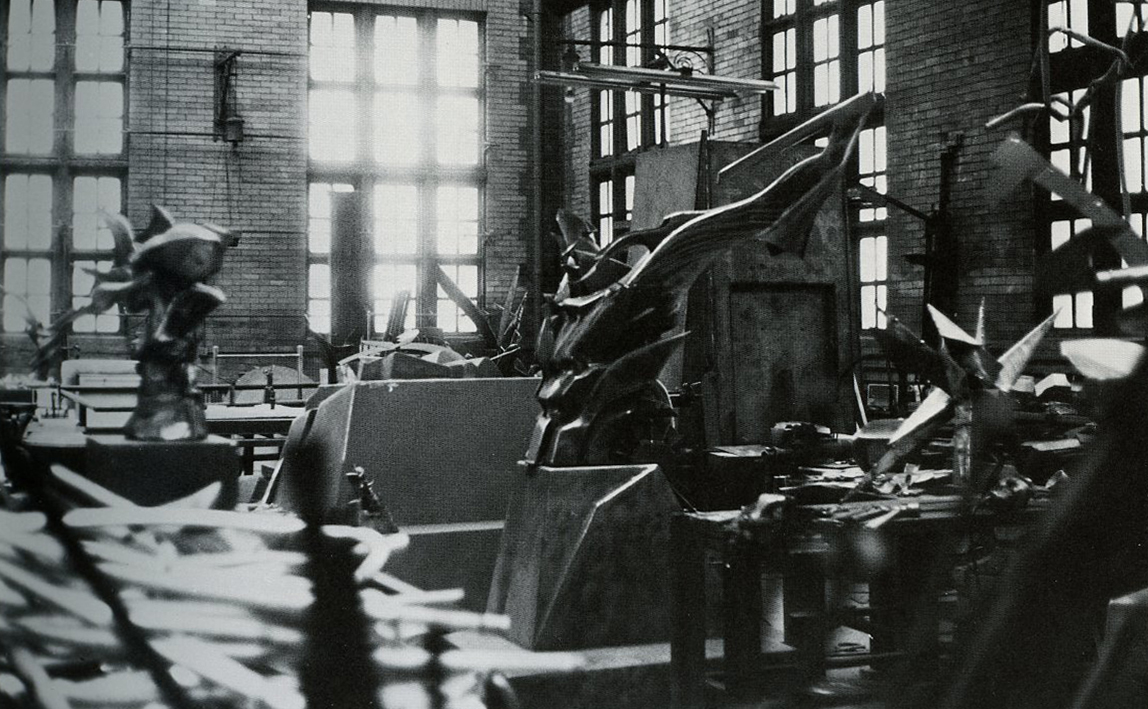

A dog-eared photograph sits atop a pile of papers in Richard Hunt’s office cubicle, a relatively quiet place outside the industrial din of his huge studio. The photo, circa 1909, is of a large construction site with workers in handlebar mustaches muscling wagonloads of steel. Two giant generators—resembling props from Chaplin’s “Modern Times,” dominate center-stage.

The eighty-year old image is a portrait of Richard Hunt’s studio, originally built for a Chicago Railways Company substation. The generators, marvels of technology at the time, powered the nearby elevated and trolley lines. Around 1970, the transit authority built a new compact plant direcdy under the elevated line and the city declared the former site surplus property. The whole pace was stripped of copper and other salvageable material except for the massive 25-ton bridge crane that spans the width of the skylighted building. Enter Richard Hunt and the stuff legends are made of.

Hunt describes himself as a “very casual student of industrialization.” The quirky circumstances of uncovering the rare photograph and its honored perch in Hunt’s cluttered office weaves a metaphor around his work that embraces complex notions of salvage and rebirth, the fragile relationship between art and industry. The armada of welding tools and hilly piles of chrome bumpers and stripped aluminum lawn furniture reinforce the context of found objects transformed.

Hunt climbs a battle-scarred ladder, props one foot precariously on a tool strewn work table and hefts his hammer. Two assistants hover nearby, their faces hidden by welding masks. A cardboard template outlines . the spiky thrust of a steel form that is about to be married to the rest of the sculpture, at this point, tentatively titled Reconstructed Wing Generator. Hunt whacks away with brutal precision. The assistants wait for instructions, torches in hand. Hunt scurries off the 15 foot high sculpture with a surprising grace, the intended steel appendage in hand. More whacks on the anvil, a squinty stare at the in process construction and another scramble to the top. This goes on again and again. The air is a light show of orange sparks from the oxy-acetylene torches. An angry-sounding grinding tool kicks in, more sprits fly and the uninitiated plug their ears and shut their eyes.

The images and sounds reminded me of the Greek Hephaestus, god of fire and metalworking. Since Hunt’s work—from Arachne in 1956—celebrates myth (Athena turned the weaver Arachne into a spider) and the alchemic transformation of one thing into another, the fleshing out of Hephaestus’ story fashions a parable for the artist.

As with all artists of stature, it is dangerous to lean too hard on one assumption. The beady eyes of the myth-generated Arachne did make Hunt famous when he was still a student at the Art Institute of Chicago, enough for the Museum of Modern Art to snap it up the year he made it and use it for the cover of his retrospective catalogue in 1971 when Hunt was 35 years old, but other influences vie for equal time. Much has been written and Hunt is often quoted on the influence of the Spanish sculptor, Julio Gonzalez, and the first time he saw that work in 1953 at the Art Institute in a show imported from MOMA and curated by Andrew Carnduff Ritchie, “Sculpture of the 20th Century.”

Flyaway (Etoria), 1987, bronze cast, edition of 5, 77x35x32 inches

Gonzalez’s wrought iron, Woman Combing Her Hair and the welded sheet iron, Le

Montserrat, both from 1937, were fertile images for the emerging artist. David

Smith called Gonzalez, “the first master of the torch” but it was Gonzalez’s

vision of “drawing in space” that shook up Hunt. “In the disquietude of the

night,” wrote Gonzalez, “the stars seem to show to us points of hope in the sky…it is these points in the infinite which are precursors of the new art divided to draw in space.”

Gonzalez was not the only artist Hunt took in during that important sculpture exhibition. The floating forms of Jean Arp and the cubist-constructivist Study for Construction in Space by Naum Gabo with its revolutionary use of brass net, plastic and stainless steel wire, spurred Hunt’s future works. Two earlier pieces, from 1913 and 1914 completed the almost bionic assembly of the eager artist who had to teach himself to weld since that activity had not yet become the vogue in art schools. Raymond Duchamp-Villon’s extraordinary bronze, The Horse and Umberto Boccioni’s flame-like Unique Forms of Continuity in Space still are stars in Hunt’s pantheon.

In Boccioni’s “Technical Manifesto of Futurist Sculpture,” written in 1912, he condemned the oppressive weight of the Greeks and Michelangelo on European contemporary sculpture as well as the academic ardor for the nude figure. He proposed a sculpture of movement and atmosphere. “…There is more truth in the intersection of the planes of a book with the corners of a table … than in the twisting of muscles in all the breasts and thighs of the heroes and venuses which inspired the idiotic sculpture of our time.”

Showing humor and humility, Hunt welded a piece and titled it, Antique Study After Boccioni, compressing and transforming a still radical polemic into an object of wit and desire. The recent resurgence of interest in Futurism especially Pontus Hulten’s epic show at the Palazzo Grassi in Venice in 1986 and the more recent Boccioni exhibition at the Metropolitan, exemplifies Hunt’s long-sighted grasp of this important and no longer obscure artist.

It is a curious phenomenon that most of what has been written about Hunt has consisted of liberally quoting the artist’s own statements as if his icon-like work was not cut out for pedestrian interpretation. The public perception of his art is grounded in older work as Hunt’s classic piece from 1958, Hero Construction. It stands tall between a Mark Rothko and Clyfford Still, and across the way from David Smith’s Tanktomen No. 1 in the new Rice Building galleries of the Art Institute. Poised like a war amputee, the peg-legged warrior seems to breathe the engine fumes of war, fierce and jerry-built from the junkyard. Hero Construction was included in Hunt’s first New York exhibition at the Alan Gallery in 1958 but its distinctly figurative visage is a far cry from the way his sculpture looks today. In a sense, the net viewing public is moored, mistakenly so, to that older expressionist style. For that reason, a gulf exists between understanding his earlier work—which relied heavily on found objects and Gonzalez’s concept of drawing in space—and the more recent, and much larger hybrid forms that evolved after his move to the Lill Avenue studio.

One aspect of that change involved Hunt’s concern that “…the whole idea of drawing in space became trivialized,” that more and more sculptors were missing Gonzalez’s point and “drawing on space.” Hunt’s shift away from the linear-spatial aspects of his welded-constructed sculpture to the exploring volumetric issues of three-dimensionality, broadened the surface of his sculptures, giving the work more mass and less reliance on the calligraphic slimness of his sweeping lines. The simultaneous expansion and compression of forms, at times resembling rock formations, rudely exposed with cross-sectional views that poked holes in their massiveness, illustrate the artist’s hunger for experimentation, pushing lines of inquiry away from the familiar. He did not abandon his pedestal-jumping “aerographic projections” but hunkered down to more “volumetric

things.”

Richard Hunt’s Lill Ave. studio, Chicago – from L to R: Torso Hybrid, Wing Generator, Point Form II

Part of the extension in scale stems from Hunt’s involvement with public sculpture commissions that now number close to 70 works. Shortly after his back-to-back retrospectives at MOMA and the Art Institute in 1971, Hunt relaxed the output of his “self-generated” studio work and focused his energies on both civic and corporate sculptural projects. You need a map to track the work, from his elegant Fox Box Hybrid perched in front of a pair of Mies can der Rohe apartment towers on Chicago’s lakefront to the more massive and emotionally charged I Have Been to the Mountain, a memorial to Martin Luther King, Jr., in Memphis, Tennessee.

Hunt made an important connection between the functionalism of industry—of exploiting certain technologies to create a product or service—and the organic process of the artist in his studio. Like the interlocking relationship between artist and craftsman in the Renaissance, Hunt discovered he too could work closely with metalsmiths and steel fabricators, collaborate with architects and city planners and engage the bureaucracy in order to achieve his three-dimensional public statements.

Eagle Columns, slated for a landscaped site virtually across the street from his studio, in Jonquil Park, is one of Hunt’s most ambitious public works to date, both in scale and evocativeness. Its ascending trio of cast bronze and aluminum aeries transforms what had been an ordinary playing field into a mythical landscape. Apart from the extraordinary forms and their ability to evoke a sense of spiritual growth, the piece also tells a story. Hunt, in this instance, mines a vein of local history, of two Chicagoans who happened to be neighbors in the late 19th century, one a politician, the other, a poet. Vachel Lindsay’s “The Eagle That Is Forgotten” was written for his friend, John P. Altgeld, a former governor of the state and the namesake of the street that abuts Jonquil Park. Hunt peeled back layers of time and cultural dissonance, improvising like a jazz musician the textural richness of two forgotten men into a new and abstract composition. The poem opens: “Sleep softly.. .eagle forgotten . . . under the stone. Time has its may with you there, and the clay has its own.”

Hunt hankers for a world view, multi-dimensional, embracing both past and present, and in a stubborn way, thrashing towards the future. That is why his work hits so many visual buttons, like an alternating current of expressionist and surreal energy. It is a spectacular view, high up in the aluminum nests of Eagle Columns.

Hunt walks a tightrope between his public sculpture and studio art. At one moment he describes his “self-generated” work as “going into the studio and doing it because I feel like it…obviously that takes on a different quality because it is more open-ended. The change as I see it is in the process of the work. But in a large-scale commission piece, certain things are determined and you can’t go off on a tangent.”

Flyaway (Etoria) is stationed at the interior stairway of Hunt’s Chicago studio. Just over six feet high, it appears already in flight, its great bronzed wings manipulating the air, soaring to that star-studded sky Gonzalez wrote about. Apart from its graceful organic form, the sculpture bristles with an acidic blue-green patina, imbuing it with an alchemic glow. It is a bold reminder that Hunt forges an amalgam between the natural and the industrial. Chameleon-like, the patina changes with the available light and as you move past the piece, circle it, come back to face it frontally, the lines change, the form seems to accelerate faster in space as if boosted by a second stage.