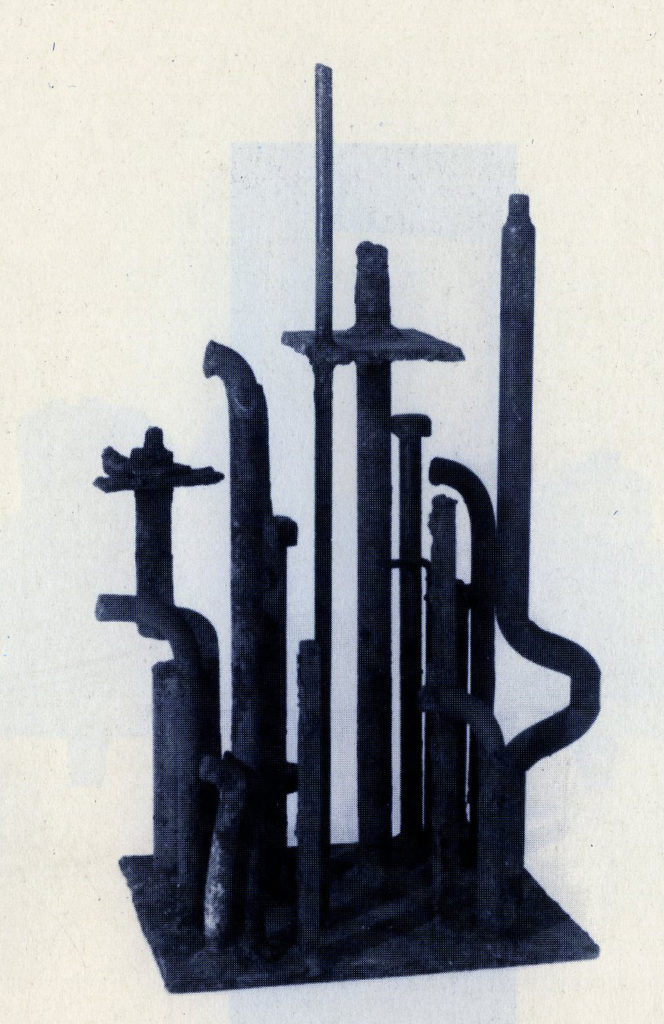

Richard Stankeiwicz, Grass People II, 1956, 18 x 7 x 9 inches, rusted steel

Sabato Rodia’s “Watts Towers” was recently declared a national landmark, thirty-odd years after its completion in 1954. The soaring structures of three 100-foot high towers were constructed out of broken bottles, pottery shards, sea shells, iron and chicken wire. Rodia had created his own Gaudi-like skyline.

The notion of “found objects” and artists finding alternative uses for things that others consider junk, has been around since Picasso inserted some upholstery fringe to his 1912 “Still Life.” The ultimate image from this rich cache of museum-quality detritus is Picasso’s 1943 assemblage, “Head of Bull,” consisting of a leather bicycle seat and curved handlebars.

Bicycles were a rich source for cannibalization, exemplified by Marcel Duchamp’s “Bicycle Wheel” from 1913, its fork impaled through the seat of a wooden stool. Duchamp’s ready- mades were carefully chosen, according to the artist, so they would lack any aesthetic appeal. The Buddha-like shape of his 1917 “Fountain” (the famous porcelain urinal) is an object of extreme beauty, despite the artist’s intention to find the mundane.

Ivan Puni, the Russian avant-gardist, experimented with collage techniques and real objects in his 1914 “Still Life-Relief with Hammer.” The reliefs were left behind in Russia and presumably lost when he emigrated to Berlin in 1920.

Along with Rodia, Picasso, Duchamp and Puni, there’s considerable baggage bearing the tag of found objects. “Lost & Found” offers a glimpse at fourteen sculptors discovering their own trails in this richly encrusted medium.

“Lost” means no longer visible, that is, until someone else sees it again or constructs an image in such a way that it becomes visible and real to others. This re-vision of the object’s utility is the essence of the transformation.

The notion of found can be as surreal as the “floatsam-jetsam” Joyce observed as it rushed along a Dublin canal in “Ulysses’ or the serendipitous “find spot” where Claes Oldenburg spied a kid’s catcher’s mitt toy on a shelf in a Chicago Woolworth’s. The mitt became a portable icon.

As in Antonio Gaudi’s Guell Park in Barcelona, with its undulating benches abstractly col- laged with the discarded and multi-colored shards from a tile factory, the artists in this exhibition mine a deep vein of found material. It ranges from broken barstools rescued from the Bowery to store bought samples of pre-stained moldings and flocked wallpapers, normally utilized for home improvement jobs.

“Lost & Found” is particularly appropriate in a consumer society (as in Barbara Kruger’s blown-up maxim: “I Shop – Therefore I Am”), where obsolescence occurs before the ordained object gathers dust on the shelf.

Things are bought, used and thrown out. Sometimes that process — it used to be the rag-picker or junkman soliciting refuse destined for the dump — is short-circuited. An artist gets hold of the object, transforms or places it in a context in which its original purpose is obliterated. Jean Dubuffet called his “Texturologies” from the mid-1950’s “…nothing but small patches of earth from a perpendicular view.”

“Lost & Found” is fragmented, puzzle-shaped and resurrected from somewhere. It carries the impulse of Kurt Schwitters’ compositions — the re-configured bits of bus tickets, chocolate wrappers and cigarette logos, picked off the bomb-pocked streets of London by the ex-patriate German Dadaist.

“Lost & Found” is not a history show except for the inclusion of Richard Stankiewicz’s rusted sculpture, first exhibited in 1956 at the Hansa Gallery in New York. For a short time in the mid-1950’s, Stankiewicz dominated the vanguard of urban junk artists who elevated eviscerated auto parts and salvaged boilers to a new and used art form.

During an interview for the Archives of American Art in 1963, Stankiewicz told Richard Brown Baker (who generously lent “Grass People II” for this exhibition) “…I make sculpture according to my ability to see and to construct, and the work will be as profound or as shallow as I am.”

Stankiewicz wrote about the moment he “found” his sculptural path and it evokes a recyclable metaphor for the underpinnings of this show. It took place during the early 50’s while the artist was excavating the backyard behind his loft building, re-establishing what had once been a garden. His spade hit brick and old hunks of metal. “I sat down to catch my breath and my glance happened to fall on the rusty iron things lying where I had thrown them, in the slanting sunlight at the base of the wall. I felt, with a .real shock—not of fear but of recognition—that they were staring at me. Their sense of presence; of life, was almost overpowering.” Stankiewicz bought welding gear and a do-it-yourself book on the subject and made his first sculpture.

Assembling a disparate group of sculptors whose work touches the boundaries of found objects with varied imprints is a risky undertaking. The glue that holds these artists together is the Elmer’s of memory, the quality that evokes associations to other places and experiences.

The intention behind this selection is to extend and refine the roster of artists utilizing found objects to express their own sculptural vision. It is akin to what the viewer experienced observing Joseph Beuys’ rescue convoy of sleds and gray blankets as they snaked along the Guggenheim Museum’s ramp during his retrospective in 1979. A cobbled memory bursts from these sculptures: The German Luftwaffe pilot shot down in the Crimean mountains, wounded, freezing and ultimately rescued by Tatars who wrapped him in layers of felt and fat. The two materials became symbols of regeneration for the artist. Whether that history is real or invented no longer matters because Beuys seized it and made it his own. He called it “a kind of autobiographical key.” “Lost & Found” turns that idea into a temporary stage for new forms.