Francis Bacon, “Seated Woman”

“Bacon’s Women,” the straight forward title at the Upper East Side outpost of Ordovas (November 2, 2018-January 11,2019), consisted of just three single panel oil paintings and two triptychs, but even with that seemingly scant checklist, the addendum to the pictures, including vintage black and white John Deakin photographs of the three women depicted, as well as filmed vignettes of some of the participants, infused the unusual exhibition with a distinct layer of historicized grandeur.

The setting helped, an elegant townhouse with works rationed along the ground level and first floor, so you have to climb some stairs to get to all of Bacon’s women.

The theme is also a kind of Me Too movement eye-opener, helped in part by a slim but oversized catalogue (£30) with the cover replicating the distressed and creased image of Ingres’ multi-figured “Le Bain Turc” reproduction from 1862-63 that was once pinned up somewhere in Bacon’s London South Kensington studio.

It was also news to me that Bacon painted more nude women in his decades of practice than men, according to catalogue essayist and Bacon catalogue raisonne author Martin Harrison, a bit shocking in the sense of the artist’s storied preference for male lovers and tough guy muses.

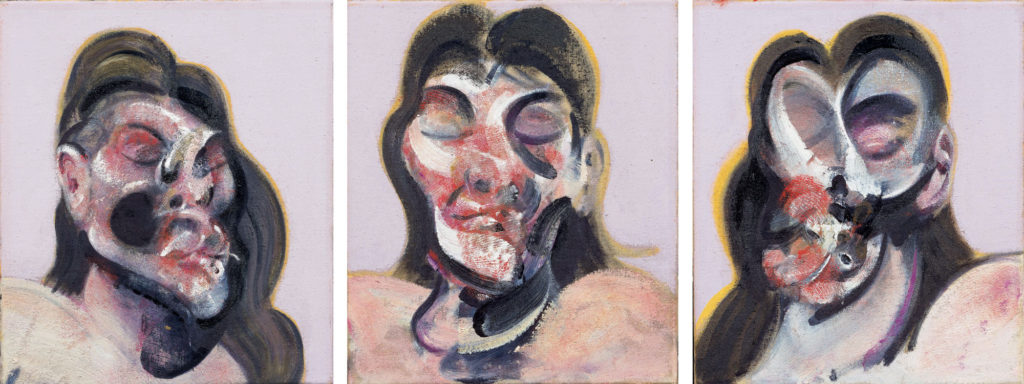

Francis Bacon, Three Studies of Henrietta Moraes, 1969

Bacon also picked three of his closest female friends and confidantes, including Muriel Belcher, the Delphic like bar keeper/owner of the Colony Room (1908-1979), Henrietta Moraes, the Soho model and nightclub reveler who Bacon painted some 23 times (1931-1999) and Isabel Rawsthorne, the art and stage design school trained beauty who famously sat for Andre Derain and Alberto Giacometti in Paris and who Bacon painted some nineteen times (1912-1992).

Though not in that line-up, Valerie Beston, Marlborough Gallery’s petite and proper gallery director and key Bacon caregiver since the artist joined the gallery in 1958, and who Bacon gifted and inscribed a tremendous self-portrait to her from 1969 and that sold at her estate sale at Christie’s London in 2006 for a whopping £5.16/$9 million (at the time), was another kind of muse.

One of the most startling works in the exhibition, all of which date between 1961-1970, is “Seated Woman” from 1961, measuring 64 7/8 by 55 7/8 inches, depicting Muriel Belcher as a hunched over and contorted nude seated on the edge of a bed, her body language twisted with Baconesque torque. Her swirling face, fleshy, pink skin tones and the lavender/lilac colored background, deliver a howitzer blast of debauched angst.

The painting, not surprisingly, has figured large in Bacon’s market, having last sold at Phillips New York in May 2015 for $28.1 million and prior to that, at Sotheby’s Paris in December 2007 for €13.7/$20.1 million.

(Apart from his canonical status as an enduring and key 20th Century artist, you can’t go far these days without some reference to Bacon’s market).

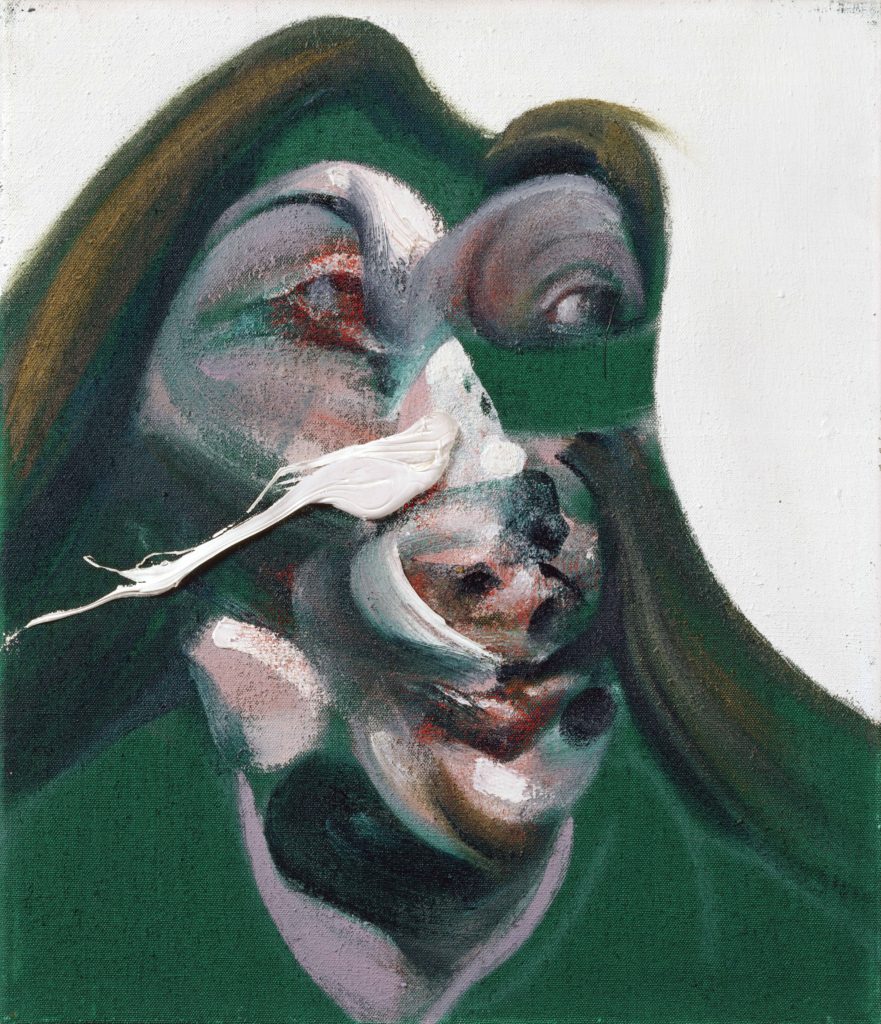

Francis Bacon, Study for Head of Isabel Rawsthorne, 1967

On a smaller, 14 by 12 inch scale, Bacon’s remarkable “Study for Head of Isabel Rawsthorne” from 1967, held a pride of place spot above a fireplace mantle, consuming the wall as if it were ablaze.

Her long mane of dark hair and piercing eyes are wide open in wonder or perhaps shell shock from the terrific force of pigment thrown on canvas.

The painful close-up of the model’s face is obscured in part from a plume of ejaculatory white paint flung on her nose, causing the viewer to wonder its purpose.

In Michael Peppiatt’s “francis bacon in your blood-a memoir” (2015), the writer noted that Bacon painted Isabel Rawsthorne “about as often as George” (Dyer) and that her portraits have “the mesmerizing power of an Egyptian goddess.”

George Condo, “Memories of Isabelle”

The painting was removed during the last week of the exhibition and returned prematurely to its anonymous owner, only to be surprisingly replaced by a freshly executed, signed and inscribed George Condo reprise of the portrait, in study form with scribbled notes on the margins about colors to place. Condo titled it “Memories of Isabelle.”

Bacon never painted ‘live’ from the figure, only from commissioned photographs that he directed through his surrogate stager, John Deakin, who is also known for having pawned off some of his nude photos of Bacon’s women to bar mates for ten shillings a pop.

“I was really furious at the time,” recalled Moraes in Daniel Farson’s “The Gilded Gutter Life of Francis Bacon” (Vintage 1994), “then I thought it was so funny! But only ten shillings! How dare he!”

In Bacon’s head and shoulders’ “Three Studies of Henrietta Moraes” from 1969, the artist delivers three distinct views of his model, all with eyes closed as in some mystical or stoned reverie, her coal dark colored hair and strong features blasted onto the favored, all-over lavender background.

Bacon’s Women installation view, Photography by Maris Hutchinson

The overall effect of the exhibition infuses the viewer with another testament to Bacon’s all-convincing power.

The inclusion of Irving Penn’s 1962 paint spattered portrait of Bacon with a reproduction of a Rembrandt self-portrait tacked on the wall behind him, further burnishes the authenticity of the exhibition.

As a footnote, the Penn photograph sold at Christie’s London in the single owner “The Collection of the Late Miss Valerie Beston” in February 2006 for a record £187,200/$326.664 (est. £15-20,000).

Irving Penn’s 1962 paint spattered portrait of Bacon with a reproduction of a Rembrandt self-portrait tacked on the wall behind him.