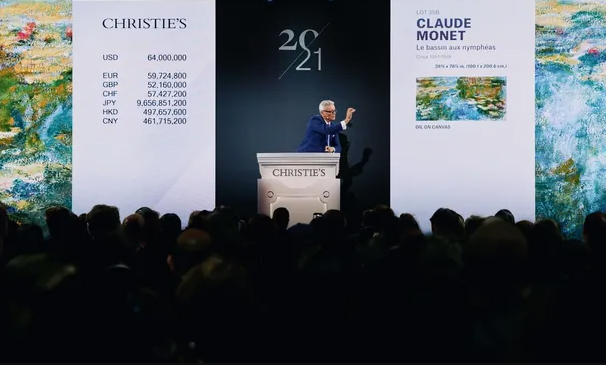

Jussi Pylkkänen took the rostrum for the last time this evening at Christie’s 20th-century evening sale. Courtesy of Christie’s Images Ltd

Swan song of veteran auctioneer Jussi Pylkkänen made $640.8m—the house’s highest total for a non-single-owner sale in six years.

It was the end of an era yesterday (9 November) at Christie’s 20th century evening sale in New York. The auction was the last to be helmed by Christie’s global president, Jussi Pylkkänen, who leaves the firm after 38 years.

Perhaps propelled by the veteran auctioneer’s swan song—and certainly dampening fears of a weakening market emphasised by Christie’s lacklustre 21st-century evening sale earlier this week—the house brought in $543.4m ($640.8m with fees). This is its highest result for a non-single owner sale since November 2017, when it made $785.9m (with fees), more than half of which came from the $450.3m sale of the Salvator Mundi.

Last night’s total almost hit its $660m high estimate (calculated without fees), and saw a healthy 97% sell-through rate by lot, with two of the 63 works withdrawn. Six artists auction records were set, including those for Barbara Hepworth, Richard Diebenkorn and Joan Mitchell.

On the guarantees front, just over half of the works were sure to sell: four were covered in house, a further 27 by third parties.

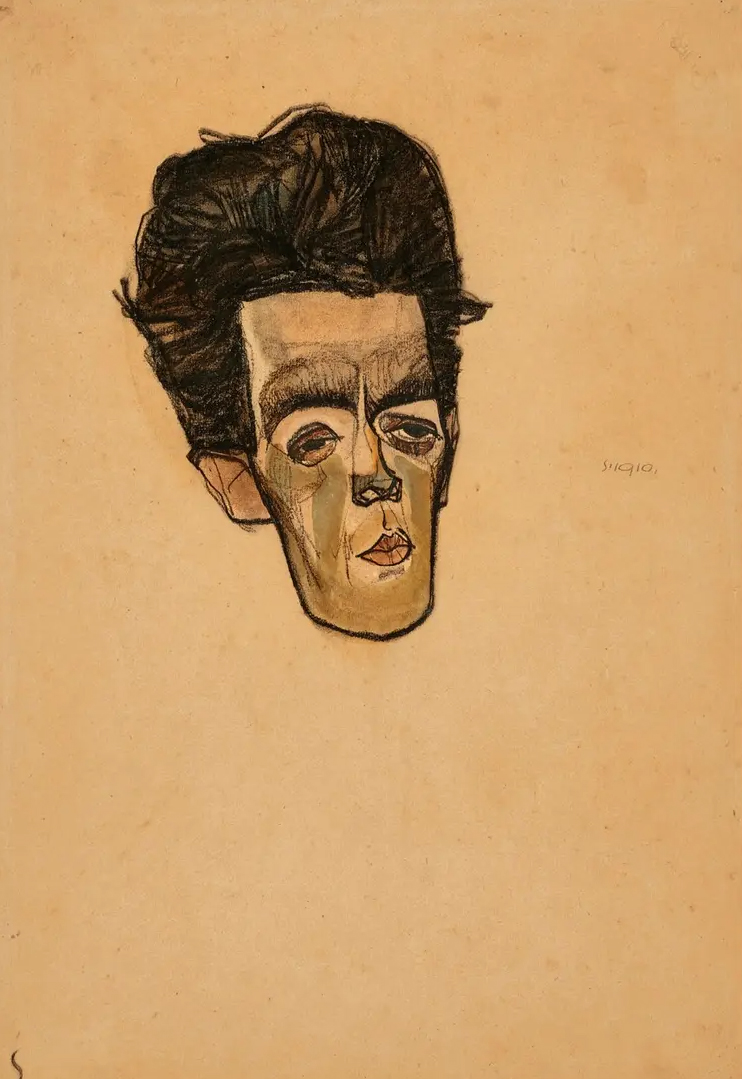

Egon Schiele’s Selbstbildnis (1910). Courtesy of Christie’s Images Ltd

The long evening got off to a bullish start with Egon Schiele’s Selbstbildnis (1910), a spare watercolour and black crayon paper work that sailed comfortably past its $2m high estimate to make $2.3m ($2.8m with fees). It was one of three restituted watercolours by Schiele from the former collection of the Viennese cabaret and film star Fritz Grünbaum. The other two also brought success. Ich liebe Gegensätze (1912), executed when the artist was imprisoned at the age of 21 for having sex with a minor, sparked a bidding war among a half dozen bidders and realised a whopping $9.2m ($10.9m fees), almost four times its $2.5m high estimate. A few lots later, Stehende Frau (Dirne), also from 1912, brought $2.2m ($2.7m) against an estimate of $1m-$2m.

Richard Diebenkorn’s Recollections of a Visit to Leningrad (1965). Courtesy of Christie’s Images Ltd

One of the night’s star lots, Arshile Gorky’s delicate abstraction, Charred Beloved I (1946), sold for a record $20m ($23.4m with fees). The work, which was painted the same year that a fire broke out in the artist’s studio, came to the market backed by a third-party guarantee and with an unpublished estimate in the region of $20m. It carried an attractive provenance too: it was consigned by the major collector and film executive David Geffen, and had also previously been in the collection of publishing magnate S.I. Newhouse. It easily topped the artist’s previous auction record, for $14m, set at Christie’s in November 2018.

Another high flyer was Richard Diebenkorn’s Recollections of a Visit to Leningrad (1965), a large sun-splashed abstract painting, which was making its first appearance at auction. It sold to an anonymous telephone bidder for a record-shattering $40m ($46.4m with fees) against an unpublished estimate in the region of $25m. This crushed the previous $27.2m record for the artist, made by Sotheby’s New York in May 2021 for Ocean Park #40 (1971).

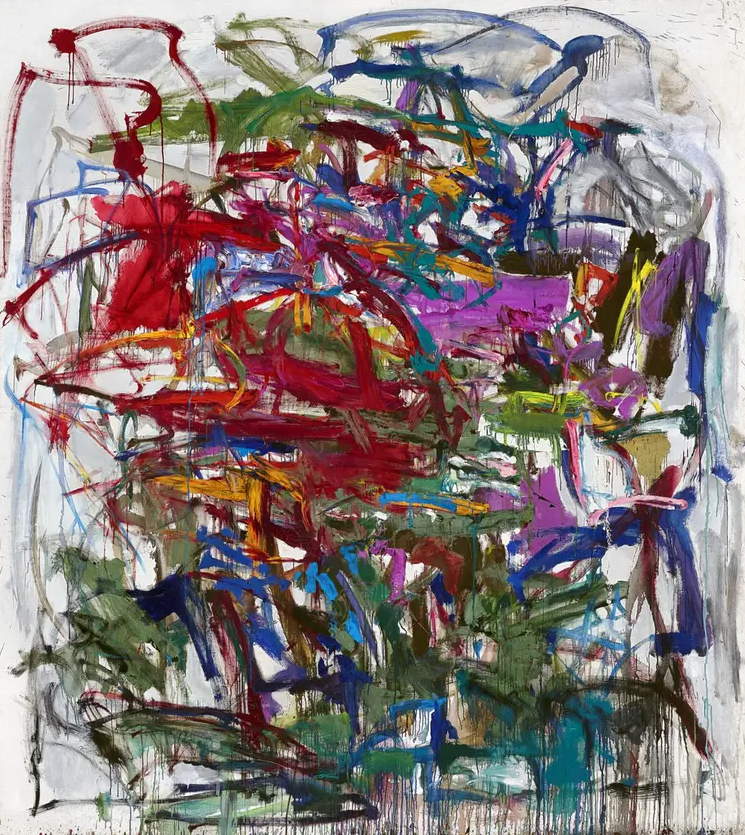

Joan Mitchell, Untitled (around 1959). Courtesy of Christie’s Images Ltd

American abstraction saw strong results throughout the evening and helped to dampen perceptions, at least for this evening, of a weakened or nervous market. Joan Mitchell’s densely packed composition Untitled (around 1959) had, like the Gorky and the Diebenkorn, never before come to the block. The guarantee-backed work made the artist’s record, at $25m ($29.1m with fees), comfortably within its $25m-$35m estimate. Mitchell’s previous record was $16.6m, made at Christie’s New York in May 2018 for Blueberry (1969).

Stellar performances from European heavyweights were also in evidence. Pablo Picasso’s Nu couché, depicting a voluptuous reclining figure, from 1968, soared above its $35m high estimate It sold to the dealer Larry Gagosian for $11.5m ($13.6m with fees) and René Magritte’s L’empire des lumières (1949) made $30m ($34.9m with fees). It surpassed its last auction appearance at the same house in November 2017 when it sold for a then record $20.5m (with fees).

The Picasso hailed from the estate of Jerry Moss, the late record producer and co-founder of A&M Records. Also consigned from his collection was Tamara de Lempicka’s coquettish portrait of her daughter Kizette, Fillette en rose (around 1928-1930), which sold for a record $12.5m ($14..7m with fees); Frida Kahlo’s early work Portrait of Cristina, My Sister (1928), which made $6.8m ($8.2m with fees); and Jean-Michel Basquiat’s Orange Joy (1984), acquired directly from the artist by the consignor around 1985, which brought $3.9m ($4.7m with fees). In total, the Moss group realised $54.7m (with fees).

Mark Rothko’s Untitled (Yellow, Orange, Yellow, Light Orange) (1955). Courtesy of Christie’s Images Ltd

Soon after came Mark Rothko’s sublime Untitled (Yellow, Orange, Yellow, Light Orange) composition from 1955. The painting was once owned by Paul and Bunny Mellon, who acquired the work from Marlborough Gallery in 1970. It sold to yet another telephone bidder for $40m ($46m with fees). The house-guaranteed lot was estimated in the region of $45m and was last sold at auction for $36.5m in November 2014 at a Sotheby’s New York single-owner sale from the collection of Bunny Mellon. An interim buyer had acquired it privately for considerably more.

Another group of top-tier works had been consigned from the collection of the late and storied Canadian filmmaker Ivan Reitman and his wife Genevieve. This included Picasso’s Femme endormie (1934), featuring the slumbering visage of the artist’s mistress and muse Marie-Thérèse Walter. But its performance was far from sleepy: backed by a third-party guarantee, it sprang past its $25m-$35m estimate to make $37m ($42.9m with fees).

Still in Reitman territory, Willem de Kooning’s late, large and decidedly spare Untitled III (1984) sold for $7.1m ($8.5m with fees). It fell a bit shy of its $8m-$12m pre-sale estimate, but was backed by an anonymous third-party guarantee. The Reitman group made $74.2m (with fees) in total.

In one of the few unscripted parts of the marathon evening, a trio of Paul Cézanne still lives, offered from the cash-strapped Museum Langmatt in Baden, Switzerland, added a touch of drama, with the exquisite Fruits et pot de gingembre (1890-93) going for $33.5m ($38.9m with fees). Estimated at $35m-$55m, the painting was expected to fulfill the museum’s goal of raising $44m (the campaign has been heavily criticised), and perhaps spare the other two Cézannes offered.

But that wasn’t to be. Quartre pommes et un couteau (around 1885) sold for $8.7m ($10.4m with fees) and La mer à l’Estaque (around 1897) made $2.6m ($3.1m with fees.) Part of the proceeds will also benefit the heirs of the late German Jewish art dealer Jacob Goldschmidt, who sold Fruits et pot de gingembre under duress in 1933 to Sidney Brown, the father of the museum’s founder.

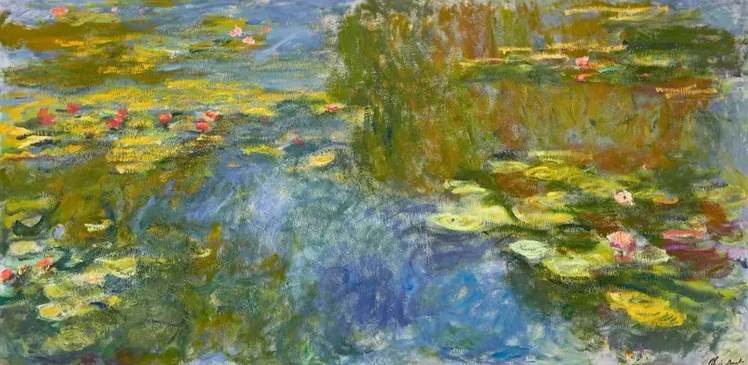

Claude Monet’s Le basin aux nymphéas (1917-19). Courtesy of Christie’s Images Ltd

The evening’s top lot was Claude Monet’s late Giverny jewel Le basin aux nymphéas (1917-19), painted at a panoramic scale of 39 by 78 inches and which made $64m ($74m with fees). It came stamped with the artist’s signature, meaning it didn’t leave Monet’s studio before his death and, accordingly, is less valuable than signed examples. Still it ranks as the sixth-most expensive Monet to sell at auction.

At this juncture, Pylkkänen announced that would be his final lot sold at Christie’s and handed the gavel over to Adrien Meyer, global head of private sales. Applause filled the room and Pylkkänen received a brief standing ovation in the Rockefeller Center. “What a night for Christie’s,” he said. “And what a night for the art market.” The evening sale action resumes on Monday at Sotheby’s with its Modern art auction.