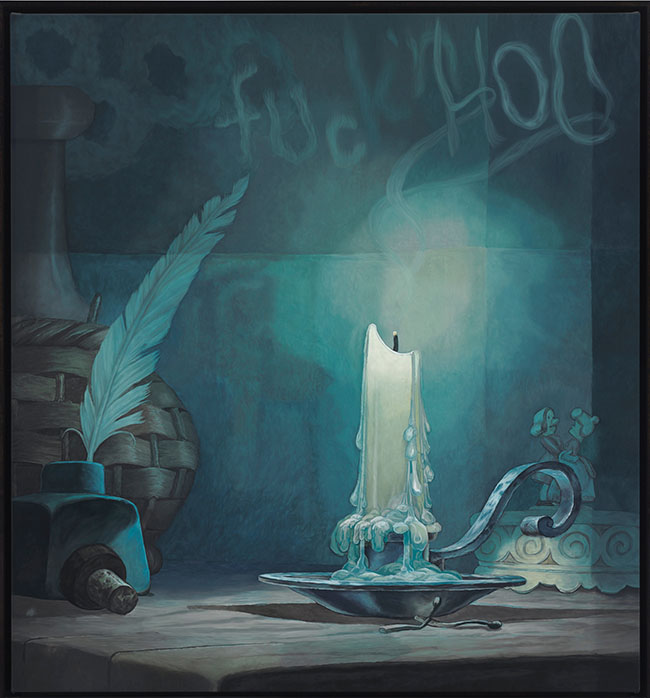

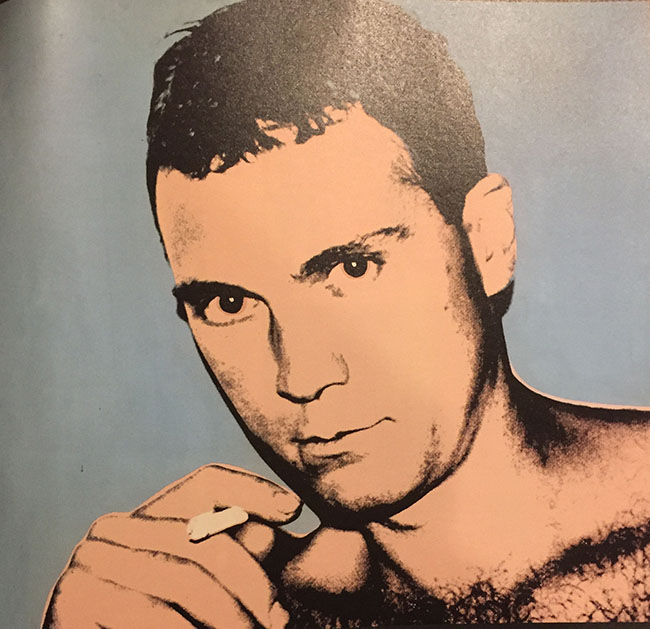

Dan Colen, 2006, Boo Fuck’n Hoo, oil on canvas, 68 x 62¾ in. (172.7 x 159.3 cm.)

Will Success last for the zero-to-$60,000 plus auction stars?

November in New YorK, the Philips’ evening sale of contemporary art began with a bang when a large oil on canvas by Lucien Smith titled Hobbes, The Rain Man, and My Friend Barney/Under the Sycamore Tree, 2011, came up for consideration. The dealer-collector Alberto Mugrabi, seated in the front row, outmaneuvered multiple phone bidders to win the painting—described in the catalogue as “an important lodestar in the artist’s aesthetic, as well as psychological, constellation”—for $389,000, more than double its $150,000 high estimate. It was Lot I of the sale, and also the first work by Smith, 25, to appear at auction.

To some observers, the sale—which was bookended by a $293,000 result for a scribbled painting by 28-year-old Oscar Murillo, who last year signed with mega dealer David Zwirner-represented the apogee of a market run amok. The Smith and Murillo sales are just two examples of a much-remarked surge in auction block prices for young artists, predominantly male, who favor a practice of large-scale abstraction.

The parlor game of determining which young artist’s star is rising or falling has disturbed the delicate ecosystem of the art market, with a six-figure auction result able to outrun a curatorial or critical imprimatur. “Let’s not refer to this success as early,” cautions Bob Nickas, an independent curator and writer who has been active in organizing group shows of young talent, “but in terms of what it really is: premature.”

Seismic shifts in both price and supply also affect the ability of ardent collectors to continue to acquire works after their initial showings in the primary market. According to New York collector Frank Moore, who over the years has focused on rising talents from Richard Prince to Wade Guyton, the current premium for ubiquitous youngsters has a chilling effect on patronage. “In the past, you were able to follow the artist sequence to sequence. Now, when they get spun around, instead of being rewarded for being there early in the career of the artist, you get punished.” He rationalizes, “I don’t mind spending a lot of money for a Christopher Wool if it becomes available because I realize that’s the fair market value, but for other cases it is an unfair market value—unfair for the artist and unfair for the collector.”

Far from spurning the speedy commercialization of their work, however, today’s young artists are apt to participate in it. “In the 1980s,” says Francesco Bonami, the peripatetic guest curator and artistic director of Turin’s Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo, “the young hot artists were also part of the curators’ attention. Museums wanted to do shows. Today it’s a little bit the opposite. It’s kind of a dangerous difference,” he adds. “Back then, [artists had] an intention to be part of the entire system. Now they’re just part of the market.”

The lines are further blurred by the present-day capacity of many dealers to mount institutional-quality presentations, while leery museum curators shy away from playing into an overheated market.

Dealer Steve Turner, of Steve Turner Contemporary in Los Angeles, represents recent darling Parker Ito, a 2010 BFA from the California College of the Arts. In an illustration of the cycle’s current breakneck speed, when Turner featured Ito in the summer group show “Wet Paint 4” in 2012, paintings from the artist’s “The Agony and the Ecstasy” series were priced at $1,800 apiece. They have since traded hands at auction for more than $55,000, and this summer Ito was tipped by the investment website ArtRank for liquidation.

“I’ve visited artists,” Turner says, “where they have 50 works stacked up in their studio because they’re going out to a [non-dealer] middleman who will source them out to certain other people and create a kind of false market. I’m not involved in it, but I see it. This is rampant.”

The phenomenon raises questions about whether any of these young contenders can thrive beyond an 18-month-long auction spurt. Close behind that query are more difficult questions about manipulation in that boisterous part of the market—or in old-fashioned financial parlance, how much of that activity is produced by “painting the tape,” creating an artificial price for a “security.” There have always been buyers who seek to game the system by cornering an artist’s market, buying low and selling high, but some say the current rewards may be encouraging irresponsible, if not outright illegal, behavior. “It would be securities fraud on Wall Street,” says a New York–based art adviser who requested anonymity. “Any time an artist is represented by multiple dealers and they collaborate on supporting the artist’s market, even at the $100,000 level, you can argue that’s a syndicate.”

Some point fingers, even admiringly, at a small cabal of dealer-collectors who always seem to be in the picture when a new artist’s market takes off. The Mugrabi family would surely be at the top of that list, having invested in now-established artists like Urs Fischer. Alberto Mugrabi explains his approach thus: “When I buy them at auction, it’s because I’ve already bought a lot of them privately, and then I can make a statement paying $300,000 for a Lucien Smith. But I would never do that to start my buying with one of these young artists.”

Mugrabi the potential for long-term disruption, however. “Will it hurt the market? Absolutely not. When one goes out, a new one comes in.” He goes on, “There are a lot of elements that determine whether an artist will persevere or not. It’s all tricky. Today they can be kings of the world—and tomorrow? They disappear” Only time will tell whether or not these young painters and sculptors can maintain their early momentum. Following is an examination of the market arcs for four such artists.

DAN COLEN

Forged in the crucible of the Rhode Island School of Design painting department in the late 1990’s. Colen, 35, son of a sculptor and a grandson of a Brooklyn antiques dealer, has been on the art market radar longer than some of today’s flavors of the moment. Having come prominence in the early woos as part of the downtown crew that included the late Dash Snow—the duo’s infamous “hamster nest” installation was shown at Deitch Projects in 2007—Colen has since vaulted into the big time.

In the past decade, the 2006 Whitney Biennial alum was featured in several headline-garnering shows, such a the Charles Saatchi–selected ” USA Today” exhibition at t Royal Academy in London in 2006 and the Jeff Koons-curated “Skin Fruit” show culled from the Dakis Joannou collection at the New Museum in zom. Colen’s first retrospective, “Help!,” opened at the Brant Foundation Art Study Center in Greenwich, Connecticut, this past May, and September saw his eighth show at Gagosian Gallery, which featured nine paintings from his “Miracle” series, large-scale abstractions that bring to mind color-charged, ethereal works by second-generation Ab-Exers like Kenneth Noland and Paul Jenkins. All were sold before the opening.

Colen has also achieved an enviable track record at auction. The campaign began in May zoo8 at a contemporary art day sale at Phillips de Pury in New York, a spawning ground for new talent. There, the graffiti-inspired Holy War, 2.005-06, a collaboration with Nate Lowman, an oil on a silkscreen ink print on canvas, claimed its low estimate of $15,000.

A year later, at a May 2009 evening sale at Sotheby’s New York, four bidders chased Untitled (Blow Me), an oil on canvas from 2.005 featuring a snuffed-outcandle inspired by an animation cel from Walt Disney’s Fantasia, to a record $386,500 (est. $100-150,000). It was only the fifth work by Colen to appear on the block.

Of Colen’s approximately 90 outings at auction, peppered with examples from his chewing-gum and faux-bird-shit paintings, few buy-ins have marred his ratings, and 34 works have hurdled the $100,000 mark after premium. Two works have sold for more than $i million, led by Boo Fuck’n Hoo, 2006, another of the Disney-inspired candle paintings; it sold at the smash-success, heavily guaranteed “If I Live I’ll See You Tuesday” sale at Christie’s New York in May tor $3,077,000 (est. $2-3 million). It was understood to have been consigned by a major Italian collection and was originally acquired from Peres Projects, the Los Angeles/ Berlin enterprise run by Javier Peres, who specializes in launching fresh talent. The dealer, who currently represents budding art stars Alex Israel and David Ostrowski, recalls that he sold the Colen painting in 1006 for $22,500.

Still, with all his market muscle, Colen is represented in only two museum collections, the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Astrup Fearnley Museum of Modern Art in Oslo. “Up to now,” says Peres, “it was just accepted that museums have the first and last word” on an artist’s reputation. “Now there’s a shift to collectors who put their money where their mouth is and who decide who’s in and who’s out. The big collectors think he’s in.”

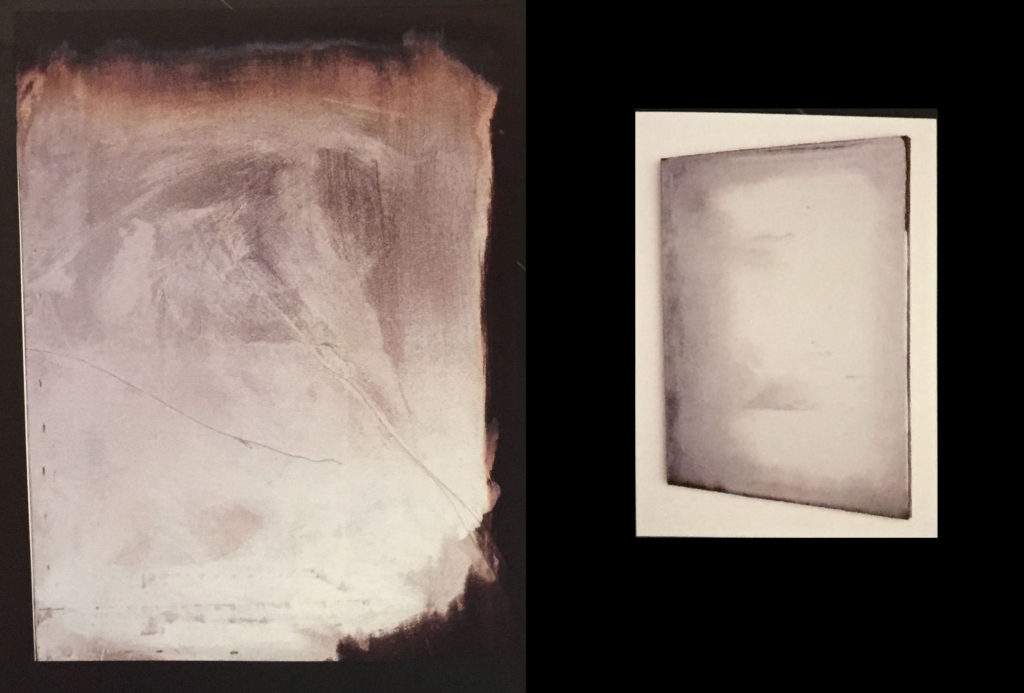

Two untitled silver paintings from 2009 by Jacob Kassay. The one on the right sold for $86,000 at Phillips in November 2010; the one on the left fethced $290,500 at the same house in 2011.

JACOB KASSAY

Kassay is a graduate of the State University of New York at Buffalo, home of the storied HaLLWalls gallery where Pictures Generation artists including Cindy Sherman and Robert Longo first showed, and where Kassay made his debut in zoo6. The 30-year-old artist has already participated in approximately 50 group shows, ranging from the 8th Gwangju Biennale, curated by Massimiliano Gioni in zoro, to the Klaus Biesenbach and Hans Ulrich Obrist-conceived “Expo New York” at MOMA PSI IN 2013. Unlike some of his market-meteorite contemporaries, Kassay garnered a museum outing, albeit a modest one, with his chemically produced abstract paintings. They were featured in “Deflections,” a 2011 solo show at London’s ICA, where catalogue essayist Peter Eleey wrote, “Kassay’s silver works most immediately bring to mind Yves Klein’s fire paintings, but also evoke a range of other abstractionists Ad Reinhardt, Robert Ryman—”with a preference for monochrome.” That same year, Kassay had a solo exhibit at the now shuttered L&M Arts, Los Angeles, during the short-lived, expansionist West Coast run of blue-chip dealers Dominique Levy and Robert Mnuchin.

Indeed, Kassay’s monochromatic metallic paintings entranced the art market after his first New York solo, at Eleven Rivington in February 2009, when seven pieces were hung and promptly sold for $5,800 each, netting the artist $2,900 apiece. At one point, the waiting list for the silver paintings was 8o clients deep, according to Kassay’s Paris dealer, Olivier Antoine of Art: Concept. The pent-up demand for the works was made abundantly clear when Untitled, 2009,a 48-by-36-inch canvas with acrylic and silver deposit, sold ata Phillips de Pury day sale in November 2010 for $86,500, more than 10 times its high estimate of $8,000.

Six months later, in May zor I, another glinting 48-by-36-inch abstraction, also Untitled, 2009, carrying a catalogue note that the work was acquired directly

from the artist, made a record $290,500 at Phillips de Pury (est. $6o-8o,000). That fall at Sotheby’s London, another silver deposit work from the same series, acquired by the anonymous seller from the Eleven Rivington exhibition, made £145,250 ($228,000).

There were 65 recorded auction results for Kassay between November 2010 and October 2014. At Phil lips London, Untitled, 2008, a larger, 84-by-6o-inch version

of the artist’s by now familiar alchemical abstraction, fetched a mid-estimate.£164,500 ($282,000) in July. A smaller one from zoo8 (est. $4o-60,00o) went unclaimed at the house’s Under the Influence sale in New York in September.

Kassay’s New York representative is Lisa Spellman of 303 Gallery, where last November the artist presented “IJK,” a new series of fragmented, deconstructed paintings that looked more Richard Tuttle than Yves Klein. Although Spellman, as well as his other dealers, declined to respond to an interview request for this article, it is rumored that Kassay has stopped making the silver-toned paintings—not unlike Damien Hirst’s swearing off of butterfly paintings and medicine cabinets once the market

for those overshopped works had cooled.

LUCIEN SMITH

LUCIEN SMITH

While still a painting student at Cooper Union, Smith, 25, racked up a number of obscure local group shows as well as an appearance with OHWOW gallery of Los Angeles in 2010 at the It Ain’t Fair in Miami. Those early exposures, plus a solo show debut, “Needle in the Hay” at London’s Ritter-Zamet the following year—comprising a large-scale, semi-demolished football goalpost inspired by David Hammons’s “Higher Goals” and early experiments with a paint-filled fire extinguisher—drew considerable attention shortly after he graduated.

But it was Smith’s breakout series of seven fire-extinguisher “rain” paintings, with their cleverly layered allusions to Yves Klein and Abstract Expressionism, shown at OHWOW in 2012, that started the art market wheels spinning. In June 2013, the solo-show train moved to Bill Brady Gallery in Kansas City. By then, says Brady, a transplanted New York dealer formerly of ATM Gallery, “we knew people were taking a look at Lucien, but then really realized, all of a sudden, people all over the world were contacting us and buying his work.” At the time, early versions of Smith’s camouflage paintings executed with stencils were priced at $24,000 for an 8-by-11-foot canvas That September, a two-venue exhibition, “Nature Is My Church,” alighted at Jeanne Greenberg Rohatyn’s Salon 94 in New York.

The artist’s auction initiation came just after, in November 2013, when his Winnie the Pooh–inspired Hobbes, The Rain Man, and My Friend Barney/Under the Sycamore Tree, 2011, fetched $389,000 at Phillips. The following February in London, Feet in the Water, 2012, a pale-blue rain painting in acrylic on unprimed canvas, bearing an

OHWOW provenance, sold to a telephone bidder at Phillips for £194,500 ($319,000), far above its estimate of £40,000 to £60,000 ($65,600-98,400). That same week at Sotheby’s, Two Sides of the Same Coin, a 96-by-72-inch spattered rain painting in acrylic on unprimed canvas, also from 2.012, notched £224,500 ($369,000) against the same estimate.

The Smith star appeared to dim this past May at Phillips New York, when a larger-format rain painting, Double Date, 2011, topped out at $137,000 (est. Sr oo–r 50,000). That same evening, the artist’s solo debut at Skarstedt Gallery uptown opened with is camouflage-style abstrac-tions from his new “Tigris” series priced between $50,000 and $8o,000. Skarstedt notes these were “very time-consuming to produce, and it was a small series, fewer than 30 paintings, which was very important to me and to him.”

Lucien Smith’s solo show from 2013 called “Scrap Metal” at Bill Brady Gallery

The impression of market fatigue for Smith’s work was reinforced when Boys Don’t Cry, another 2012 rain painting, appeared at Phillips London last July and sold for £116,500 ($zoo,000) on an estimate of £4o,000 to 6o,000 ($68,000-103,000). The price looked relatively tame despite almost doubling the high estimate—which is exactly the kind of danger young artists face when their market cools from red-hot to plain sizzling. “I’ve warned any number of younger artists not to be in too much of a hurry to be discovered,” says curator Bob Nickas. “Besides cutting short those essential years of development, it’s like being in a rush to be forgotten.”

Smith himself sounded battle weary during an inter-view in August on OHWOW ‘s Know-Wave radio. “I was a fucking poster boy for it,” he said, referring to his role in what he called “the flip generation.” “Every gallery is like a brothel,” continued the artist. “You have, like, new talent come in and rearrange the space, but it all looks the same: Watch me pour bleach and, like, pee on this with flowers in it and sell it for 10 grand and have Niels Kantor resell it for 5o…It’s crazy, butyou could buy a work of mine today for $8o,000 and sell ittomorrow for $350,000 through an auction.” He concluded, “If I ever make art again, I’m going to sell it at auction. I’m going to get the most amount of money I can for this object. David Hammons did it, and so can I.”

SANDRO CHIA

For a historical example of how runaway early success can affect an artist’s market for a lifetime—and a reminder that we have been here before—one need only look as far as Chia in the early 1980s. Part of the vaunted “Three Cs”—the Italian “Transavanguardia” artists championed by critic Achille Bonito Oliva that also included Francesco Clemente and Enzo Cucchi—Chia couldn’t have been in a more enviable position. Andy Warhol did his portrait in 1980, when Chia was in his early 3os, the same year he debuted at the Venice Biennale. Between 1983 and 1984, Chia had exhibitions at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Nationalgalerie of Berlin, and the Musee d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris.

Andy Warhol’s Untitled (Sandro Chia), 1980, hit the block at Sotheby’s last month with an estimate of $134,000 to $199,00.

By then Charles Saatchi, who would go on to virtually create a market by his assembly of a collection of works by the artists who came to be known as YBAS, had accumulated seven of Chia’s figurative paintings. But in 1984, Saatchi suddenly liquidated them on the secondary market, and the publicized dispersal sent Chia’s star tumbling. As recounted in Kevin Goldman’s Conflicting Accounts: Creation and Crash of the Saatchi & Saatchi Advertising Empire, Chia became incensed and sent Saatchi a telegram denouncing him as a negative influence on the art world. As Chia described that episode and impact to Anthony Haden-Guest in an August 1988 Vanity Fair article, “I thought I might as well go paint in Alaska. My telephone was ringing constantly and from that moment on, no one was ringing anymore. It was unbelievable, like you see in the movies.”

Although one needn’t worry overmuch about Chia’s fortunes—he divides his time between Miami, Rome, and his vineyard estate in Montalcino, and he had a recent show of small watercolors at New York’s Steven Harvey Fine Art Projects—his story is one to consider against today’s frothier and faster market, where prices slide from four to six figures and back in a heartbeat. Chia has racked up more than 2,000 auction results, but only a half-dozen have surpassed the $200,000 mark, most recently The Crocodile’s Wisdom, 1982, which made €218,800 ($336,000) at Finarte in Milan in March 2008.

Reached at his home in Italy, Chia offered several observations about the state of the market, then and now. “In a sense, the generation of the 198os created this art situation of the present,” he said. “In the ’80s, all this was invented from nothing—the artist, the painter, as popular as a rock star.” Asked what it felt like to experience that fame, and if he had any advice for the current young guns, Chia said, “In my case, I thought I was invulnerable. I was extremely arrogant and believed I could win any fight. What I would tell a young person would be to enjoy the success as long as it exists, because it can’t last forever.”