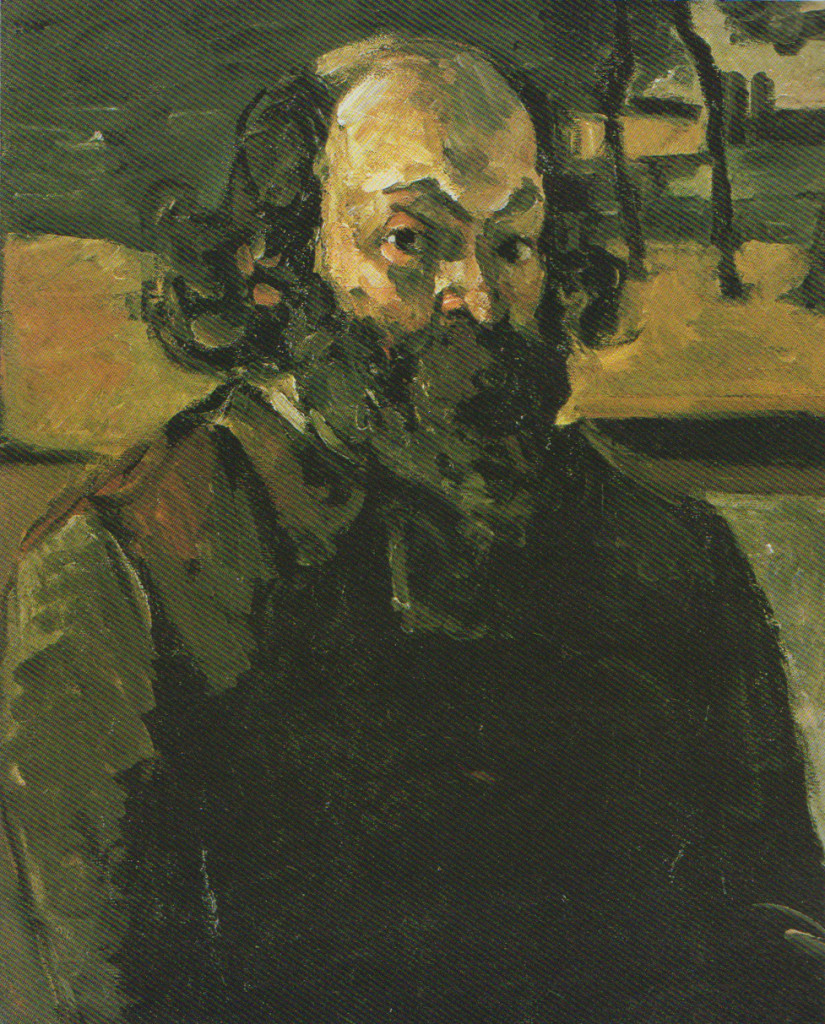

Paul Cézanne, “Self Portrait” 1875

When Arnbroise Vollard, the upstart Parisian art dealer, mounted a daring show of Paul Cézanne’s work at his tiny shop on rue Lafitte in November 1895, the critics spouted venom, ex-claiming: “the nightmarish sight of these atrocities in oil exceeds the amount of practical joking legally permissible today.

Cézanne had sent Vollard more than 150 un-framed canvases of landscapes, still lifes, portraits and multiple-figure compositions dating from as as 1868, but the dealer had room to hang only 50 of them. Still, it was the first time in nearly 20 years that the increasingly reclusive and thin-skinned Cézanne, then aged 56, had shown in Paris, the citadel of the art world. It was also his first one-man show.

While the art critics fumed, the highly respected painter Camille Pissarro dashed off a letter to his son Georges: “The collectors are stupefied; they don’t understand anything about his work…he is a first-class painter of astonishing subtlety, truth and classicism: In another missive, Pissarro raved, “These are exquisite things!” But in a letter to his wife, he accurately predicted the public’s response to Cézanne’s work: “I think it will be little understood.”

Pissarro had met Cézanne at the Atelier Suisse in Paris in the 1860s, and in 1872 the two artists often painted together at Auvers-sur-Oise. During these plein-air sessions, Pissarro encouraged Cézanne to lighten his palette, and it was in Auvers that Cézanne produced his early masterpiece, – The House of the Hanged Man: Pissarro remained a close friend and was one of a small group of distinguished artists (others included Edgar Degas, Paul Gauguin, Claude Monet, Odilon Recion, Pierre Auguste Renoir and the American expatriate painter Mary Cassatt) to recognize Cézanne’s genius well ahead of the critics and art aficionados of the day.

Paul Cézanne, “Madame Cézanne in a Red Armchair”, 1877

The year that Vollard put on the Cézanne show, an-other major painter, Gustave Caillebotte, bequeathed his collection of Impressionist paint-ings to the Luxembourg Museum. Its conservative curators blindly rejected a number of the paintings, including several by Cézanne. Ap-prised of the rejection, Vollard placed the most famous of them, “Bathers at Rest: in his shop window. (It now hangs at the Barnes Foundation in Merion, Pennsylvania.)

The enormous gap between heckling condemnation of and un-abashed ardor for this quirky and countrified outsider eventually closed, but it took several decades. Part of the reason for the artist’s delayed acceptance had to do with his irksome demeanor. Despite his deliberate peasant style of dress, crude manners and rough language, Cézanne had a magnificent education, matched by no other artist of his time except perhaps Degas. His coarse exterior grew rougher over the years, and the artist even began to fear casual human touch. Mary Cassatt met Cézanne in 1894 while visiting Monet in Giverny and ob-served: “He looked like a cutthroat with large red eyeballs standing out from his head in a most ferocious manner, a rather fierce-looking pointed beard, quite gray, and an excited may of talking that positively made the dishes rattle.

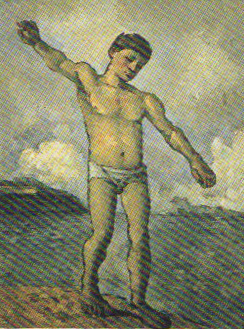

Paul Cézanne, “Bather with Outstretched Arm,” 1877-78

Today Cézanne is universally acknowledged as the kindred spirit, if not outright father, of modernism. His work became a kind of aesthetic springboard for the 20th-century movements of Fauvism, Expressionism, Constructivism, Cubism as well as abstraction in general. “However unfinished Cézanne’s work might appear, it adduces the idea of an absolute overthrow of the art of painting: wrote Paris critic Thadee Natanson in 1894. Natanson’s statement captures the essence of Cézanne’s revolutionary im-pact on the history of art, from the time it was first shown in Paris in 1874 to its debut in Berlin in 1900, London in 1905 and finally in America at Alfred Stieglitis avant-garde Photo-Secession Gallery in 1911.

The centenary celebration of Vollard’s modest yet trailblazing show is “Cézanne” the blockbuster exhibition that drew more than half a million visitors to Paris’s Grand Palais last fall and is currently enchanting huge crowds at London’s Tate Gallery (till April 28). The unprecedented gathering of more than 100 oil paintings, 35 watercolors and a like number of drawings will make its final stop at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA) on May 30 (running through August 18).

It is the first time in almost 60 years that an exhibit has reviewed the entire body of work by the mysterious master from Aix-en-Provence. Smaller, concentrated shows have focused on vadous aspects of Cézanne’s broad oeuvre, such as the late works (at New York’s Museum of Modern Art), the early works (at London’s Royal Academy of Arts), the bathers motif (at the Kunstmuseum in Basel) and the Mont Sainte-Victoire theme (at the Muse, Granet in the artist’s home-town). But no one had attempted to tackle the complex breadth and eye-jolting scope that flowed from the painter’s sable brushes and metal-edged palette knives.

According to Francoise Cachin, director of the Musees de France, it was high time for such a show. “Cézanne was the only French master of the 19th century who hadn’t been afforded an international retrospective in the post-war era: she points out. Cachin, along with Joseph R. Rishel, a senior curator at the PMA, and Nicholas Serota, director of the Tate Gallery, are the high-octane intellectual engines running the exhibition. They began planning “Cézanne” in 1992, when, as Rishel puts it, “We just divided up the world like the Pope did. I told them I’d bring in the bacon [the pictures] from North America, Francoise focused on France and Nicholas on England….What we set out to do was very mod-est in that we had no clear po-lemic to further (e.g., that the late paintings were better than the early works), but also very ambitious in that one set out to do a show that would allow visitors to get a grip on Cézanne as a whole.”

The exhibition features works ranging from Cézanne’s academic studies and sexually charged narratives of mythological subjects of the 1860s (such as the Delacroix-influenced) “Abduction” with Hercules carrying away Alcestis) to his grand finale, “The Large Bathers: painted in 1906 just before his death. For the first time since 1907, the exhibition reunites this famous canvas with its little sister, “The Bathers: a prize possession of London’s Tate Gallery. Unfortunately, none of the Barnes’s 69 Cézannes – including “Nudes in Landscape” (1905-06), considered the most resolved of the three monumental “Bathers,” could be lent for the current retrospective due to restrictions set forth in Dr. Barnes’s will.

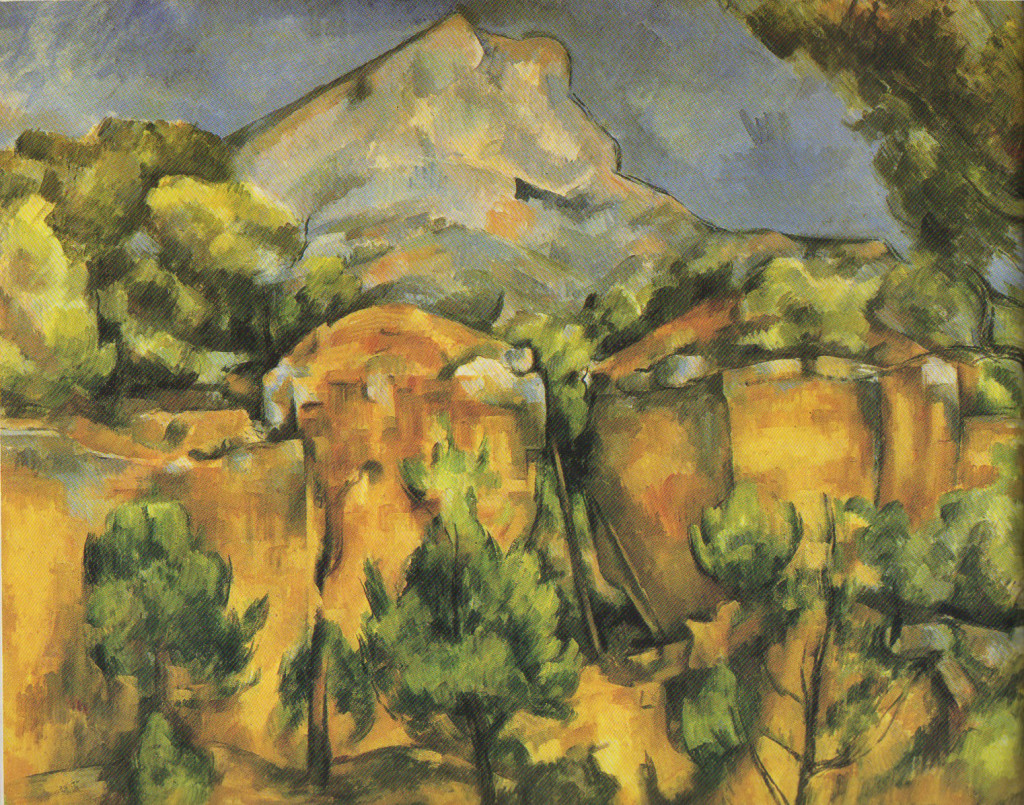

Cézanne painted some 200 works based on the nude battlers theme. Unlike his landscapes and still lifes, these paintings come from his imagination and reflect the realm of Rubens’s and Poussin’s classical world that the artist studied in the Louvre. It’s the only motif that outnumbers his renderings of Mont Sainte-Victoire, which has become the artist’s signature image. “…Wherever one finds oneself [in Aix-en-Provence], there appears in the distance the large and gray wall of Mont Sainte-Victoire, rising abruptly above the undulating valley: wrote the late Cézanne scholar, John Rewald. Accordingly, the retrospective includes 18 vistas of the famous mountain in various media.

Cézanne was a jack-of-all-trades, and the usual hierarchy of, say, portraits over still lifes does not apply. In fact, Cézanne often treated his portrait subjects-his Uncle Dominique, art dealer Vollard -as inanimate objects. The artist’s gravity-defying still lifes, rich with luscious-looking apples and fresh-cut blooms, were often painted from artificial fruit and paper flowers. Cézanne was so slow and methodical that real food or flowers would rot or wither well before the paintings completion. The tight arrangements of still life objects (many of these cherished props, such as a bleached-out human skull and chubby plaster putto, can still be seen at Les Lauves) were often propped up at odd angles and painted in such a way as to give the viewer the illusion of shifting eye levels in a single painting. Cézanne’s revolutionary pictorial devices, which became known as Cezannisme, created extraordinary distortions, such as overlapping planes and aerial perspective. They profoundly influenced the vanguard movements of Fauvism and Cubism crafted by Georges Braque, Andre Derain, Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso during the first decade of the 20th century.

Paul Cézanne, “Mont Sainte-Victoire Seen from Bibemus,” 1897

One of the more daunting obstacles in mounting a Cézanne retrospective is the near prohibitive costs of insuring these works on tour, given the astronomical prices Cézanne paintings now fetch at auction. “Still Life with Apples: for example. sold for $28.6 million at Sotheby’s New York in May 1993, the highest price for a Cézanne at auction. Fifty other works have sold at auction in excess of $1 million since 1973.

Other obstacles are less concrete. “Our basic knowledge about Cézanne’s work is very limited: write Cochin and Rishel in the catalogue preface. The artist did not date his pictures, and this strange fact has kept generations of art historians busy arguing over their chronological order. The situation is made even more difficult by the fact that the aging Cézanne became increasingly choosy as to whom he would admit into his studio, the result being that even firsthand recollections of what was on his easel from artists, critics, collectors and friends are rare. He especially abhorred journalists and avoided them whenever possible. “I curse the X…s and the few rascals who, for fifty francs, write articles that draw the public’s attention to me: wrote the artist in May 1896 to a young poet acquaintance.

During his lifetime-and even after his death-the pictorial revolution Cézanne fomented on canvas and paper stumped many critics because a critical language had yet to be developed that could convey the artist’s may of seeing. Much of his unorthodox art was simply unintelligible to the critics and general public alike.

The catalogue frankly acknowledges the continuing mystery of the man but through imaginative scholarly digging affords an overview of published critical thought on the artist from a host of European writers. One such impression could refer to the current retrospective: “Today I went to see his pictures again,- wrote lyric poet Rainer Maria Rilke (1875-1926) after viewing the Cézanne show at the Salon d’Automne in 1907. “It is remarkable what an ambiance they create. Without looking at any particular one, standing there between the two galleries, you feel their presence joining together into a single, colossal reality.”

Philadelphia’s coup in being the only U.S. museum to host “Cézanne” (a trophy akin to the Art Institute of Chicago’s recent U.S. exclusive of the Monet show) had a great deal to do with its outstanding Cézanne holdings. Its inaugural exhibition in 1928 included three Cézannes owned by Philadelphia collectors and museum trustees Carroll S. Tyson and Samuel and Vera White. After an exhaustive search for the best Cézanne on the market, the museum bought “Mont Sainte-Victoire” (1902-04) in 1936 for the then whopping sum of 536,000.

The following year, the acquisition of the even more significant “Large Bathers” 119061 from the peerless Auguste Pellerin collection assured the museum’s posi-tion as a world-class repository of Cézannes. “It was an astonishing move for an American museum at that time,” said Anne d’Harnoncourt, director of the PMA.

Not surprisingly, the purchase of “The Large Bathers” unleashed a media firestorm. The nation was still in the midst of the Great Depression, and the city’s coffers were bone dry. A cartoon in the Philadelphia Record depicts a slum-dwelling mother and child at the door of their miserable hovel staring at a jaunty messenger bearing the just-acquired canvas and its $110.000 price tag: “Lookit! I bought you a pretty picture!”

But that hostility was short-lived compared with Albert C. Barnes’s thundering denunciation of the picture after a museum press release described Barnes’s “Nudes in a Landscape: which he had acquired from Vollard in 1933, as “the second version: Barnes then held his own Press conference and called the PMA’s “Bathers” a weak example of the artist’s work and a “disgrace to Philadelphia: Barnes himself never got over the snub but the two museums have long since made up.

Paul Cézanne, “The Sea at L’Estaque Seen through the Trees,” 1878-79

Paul Cézanne was born in Aix in 1839, the son of Louis-Auguste Cézanne, a prominent hatmaker, and Anne-Elisabeth-Honorine Aubert, a former employee. They did not marry until 1844. Cézanne attended the local lycee, where he became fast friends with Emile Zola, the future literary giant. The two boys, along with another schoolmate, Jean-Baptistin Bailie, explored the arcadian splendor of the Provencal countryside, playing out the Greek and Latin stories of their classic schooling.

In 1859, Louis-Auguste, who had made a small for-tune as a haberdasher and owned the only bank in town, bought the as de Bouffan, a large estate formerly owned by the governors of Provence. Graced with a lovely drive lined with chestnut trees, the imposing house salon 37 acres of land just outside of town. This landscape was a recurring motif for the artist, who made numerous paintings of the house, the stone dolphin and lion standing guard by the pool and, of course, the magnificent trees (see “Chestnuts and Farm at the as de Bouffan,” from the Museum of Fine Arts, Minneapolis). But despite young Cézanne’s wish to study art in Paris and rejoin Zola-his chum even pre-pared a rigorous schedule for study at the Louvre on a shoestring budget-the banker insisted that his son study law.

Stormy relations between father and son as well as the son’s strong attachment to his mother and sister provide endless fodder for the Freudian crowd. The artist went to incredible lengths to conceal from his father his relationship with model and mistress Hortense Fiquet, especially when their son, Paul, was born in 1872. When the elder Cézanne learned of the liaison in 1878, he cut off his son’s stipend and the painter was reduced to relying on his increasingly famous-and generous-friend Zola for funds.

Cézanne and Hortense finally married in 1886, the year Louis-Auguste died. But the artist continued to live with his mother and sister at the Jas de Bouffan while Hortense and young Paul spent most of their time in Paris. “My wife likes only Switzerland and lemonade: wrote the artist to a friend. In fact, Hortense also had an appetite for gambling and frequented casinos more often than art galleries. Despite Cézanne’s rather distant relationship with Hortense, he produced many fine portraits of her, including one where she is in abbe-green striped dress and a distinctly melancholy mood (“Madame Cézanne with Unbound Hair” 1890-92, at the PMA).

It was also in 1886 that his 34-year-old friendship with Zola ruptured when the writer published his roman a clef, L’Oeuvre. The tragic character in the work was Claude Lantier, a brilliant but mad artist who committed suicide in front of his large unfinished painting of a nude. It was clear that Lantier’s character was loosely based on Cézanne. In his last known letter to Zola, the artist wrote, “I have just received L’Oeuvre, which you were kind enough to send me. I thank the author of Les Rougon-Macquart for this kind token of remembrance and ask him to allow me to clasp his hand whilst thinking of bygone days: It was never to be.

Despite the civil tone of his letter to Zola, Cézanne was enraged. According to Vollard’s published account of the affair, the artist protested, “How dare he say that a painter is done for because he has painted one bad picture? When a picture isn’t realized, you pitch it in the fire and start another one!”

Though Cézanne inherited a sizable fortune from his father, he continued to work and lived frugally. His restraint had little influence on Hortense, however, and they drifted farther apart. For more than a decade, the painter moved restlessly between Aix and Paris, renting nondescript hotel rooms and modest apartments and relentlessly pursuing his art. It was during this period that Cézanne became a devout Catholic, a curious development since he once considered the practice of religion akin to “moral hygiene.”

By 1897, the artist was spending most of his time alone in and around Aix. He rented a cottage in nearby Le Tholonet and obsessively painted the striking motif of the Bibemus quarry. That October, his mother died at the age of 83, leaving the Jas de Bouffan to her three children, who had no choice but to sell the beloved property and split the proceeds. Cézanne then moved to a house in the center of town, where he lived alone with his housekeeper. It was during this period that he made daily excursions to Chateau Noir, the ocher-colored house with Gothic windows that was the subject of many paintings. He even attempt-ed to buy the property but to no avail, and in 1901- the year Maurice Denis first exhibited his “Homage to Cézanne”-Cézanne bought a plot of land on the outskirts of Aix and began construction on Les Lauves. It would be his last studio.

The following year, Zola died unexpectedly, asphyxiated by a faulty chimney in his home. Cézanne was devastated and mourned alone. A year later, 10 early Cézannes from Zola’s collection fetched surpris-ingly high prices at auction, including “The Abduction” 11867, featured in the current retrospective), which brought FF 4,200- a huge price considering that a Monet landscape sold that day for only FF 2,805. Several years earlier, in a similarly impressive incident, a Cézanne landscape sold for FF 6,700, prompting a suspicious bidder to publicly demand the buyer’s name. “It is I, Claude Monet,” came the reply, according to an account published by Remold.

Despite their estrangement, Cézanne and Zola remain a remarkable duo in the history of arts and letters, even though Zola completely misunderstood the extent of his friend’s genius. His remarks in an 1896 Le Figaro review on the “abortive genius” of Cézanne did little to resuscitate their friendship. This flawed and much copied assessment of the artist continued until Cézanne’s death in 1906. Obituaries described the artist as “a mad Chardin” with “an absolute inability to stay the course to the end” and labeled his achievements as sincere but unfinished.”

No matter what critics said about Cézanne, he always main- tained remarkable self-esteem: “All my compatriots are hogs compared with me,” wrote the artist to his son, shortly before his death. Cézanne, after all, considered the Louvre “the only sanctuary worthy of my art.” In a less-inflated moment, Cézanne wrote to Vollard of his struggles: “I work obstinately, I have glimpsed the Promised Land. Will I be like the great leader of the Hebrews? Or will I truly penetrate it? I have made some progress. Why so late and with so much difficulty?”