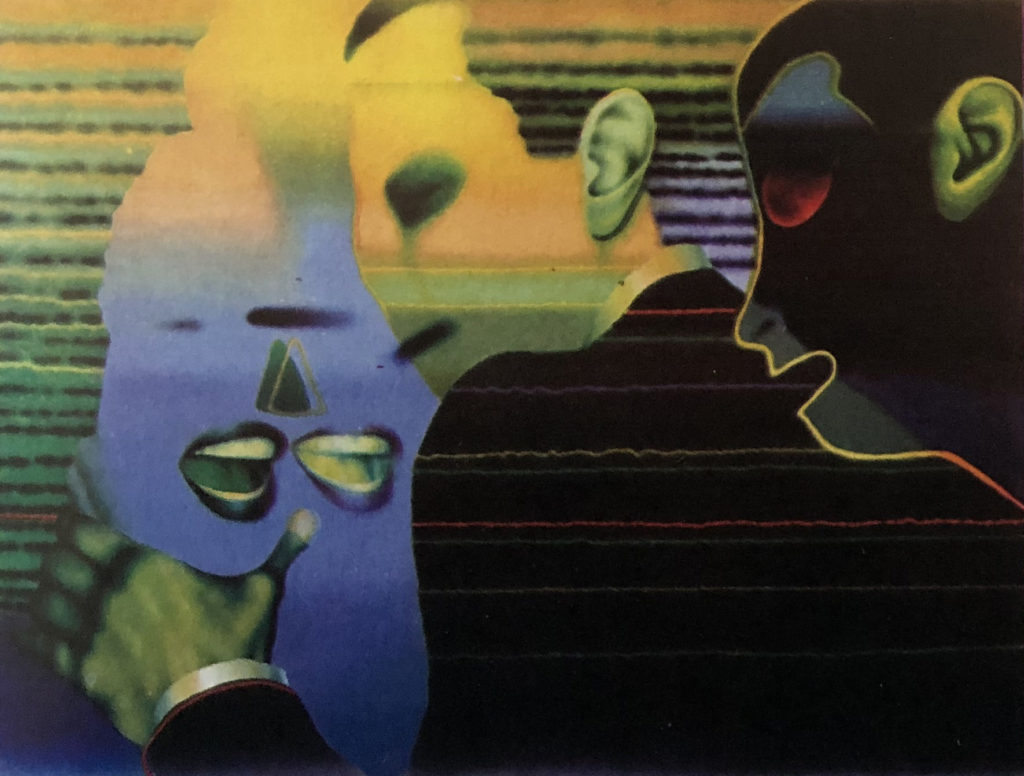

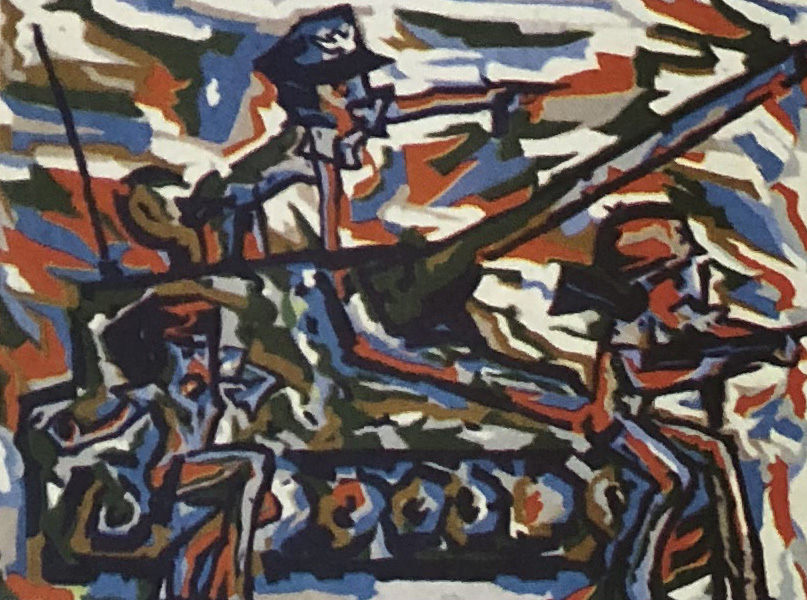

Ed Paschke, “Violencia”, 1980, Oil on canvas, 74 x 96 inches, Courtsey Phylis Kind Gallery, New York

Approaching Chicago by air, the baby blue expanse of Lake Michigan licks a long strip of white sand beaches before the vertical thrust of high-rise buildings consumes the landscape. Art Deco terracotta facades joust with the stripped-down sleekness of the glass-and-chrome Modern style, and the lusty contrast of architectural spires provides an intriguing metaphor for similar battle lines drawn in the visual arts.

In the early 1950s, while abstract expressionism was burning brightly in New York, a totally different phenomenon was producing a lot of smoke in Chicago. The images were tough and blemished by the scar tissue of World War Two. Artists like Leon Golub, Cosmo Campoli, June Leaf, George Cohen, and Joseph Goto comprised what came to he known as the “Monster Roster.” Centering on the academic strongholds of the School of the Art Institute and the Institute of Design (a Bauhaus transplant engineered by Laszlo Moholy-Nagy), “Exhibition Momentum” flung the Monster Roster group onto the fledgling art world’s map of America.

Poking through a dog-earred issue of Art News from October 1955, this writer came upon an ambitious article penned by Patrick T. Malone and Peter Selz which asked, “Is there a new Chicago School”? In 1964, similar questions framed in a longer format (Chicago Review, “Sphinx of the Plains: A Chicago View”) by Chicago critic and art historian, Joshua Kind, polished the Monster Roster patina and added some new names. Kind tipped his historian’s hat to Ivan Albright’s surreal and grotesque canvases, which pock-mark the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago. Albright’s “Picture of Dorian Gray” tugged simultaneously at the viewer’s heart and gut strings. Albright, harbinger of the new Chicago style, enshrined the human figure with an expressionistic fury that turned stomachs and cast bleak shadows over previously sunny rooms.

The frenzied activity of the 1950s and 1960s was far afield from commercial galleries. Allan Frumkin, a pioneer Chicago dealer with a fascination for the surreal similar to that which Julian Levy espoused in New York years earlier, mounted shows and encouraged artists. The Esquire Theater Gallery, Don Roth’s Blackhawk Restaurant, and Bourdelon’s furniture store on Chicago’s south side, became the “alternative” exhibition areas for this new art.

After Frumkin moved east to set up another gallery in New York, the first drumbeats of the Hairy Who, False Image, and Non-Plussed Some could be heard at the Hyde Park Art Center Gallery, in the backyard of the University of Chicago. Don Baum, artist, teacher, and perhaps, most important of all, talent scout, got the typewriters clacking and the collectors sniffing at the new brand of Imagists. Jim Nutt, Karl Wirsum, Roger Brown, Gladis Nillson, Ed Paschke, Roy Yoshida and Christina Ramberg were percolating to a different drummer that set the art world beyond the borders of the Windy City topsy turvy.

There are forty galleries listed in the current ‘`Art Now / Chicago Gallery Guide.” The Museum of Contemporary Art, opened in 1967, got wrapped by Christo in 1969 (with tarpaulin and two miles of rope), expanded in 1979, and now boasts 16,000 square feet of gallery space. Even the new stairway leading to the second floor galleries, lub-dubs to an avant-garde beat with Max Neuhaus’s permanent installation of sound sculpture.

On a recent visit to the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chuck Close and Roger Brown shared retrospective niches. Not surprisingly (if you’re attuned to Windy City art politics), the New Yorker Close beat out Chicagoan Brown for the more prestigious glass frontage of the second floor gallery. Downstairs, the environmental installation of Jane Wenger projected cropped, mural-sized black and white photographs of contorted faces, choreographed to a strange sound track of grunts and muffled shrieks.

Combing the galleries along Ontario, Ohio and Superior Streets, Michigan Avenue, and the scruffier industrial zone of West Hubbard, is a sole-wearing affair. Free-trade war zones of imagist, abstract and middle-of-the-road art elbow for attention. Gallery pedigree is easily established and stylistic predilections can he quickly determined.

For the abstract-minded, Marianne Deson and Jan Cicero Galleries are required stops. Phyllis Kind offers the strongest imagist suit, whereas in the large scale sculpture department, ConStruct, directed by Roberta Richards, masterminds the commissioning of sculpture for public spaces. Dart, Richard Gray, and Young-Hoffman Galleries exhibit a mixed grill of New York art stars alongside Chicago-based heavy-weights. Mecca for the new wave resides at the Nancy Lurie Gallery, which, strange as it may seem, is across the street from Moody Church.

While figurative and abstract artists duel for a place in the sun (or at least a page in the art magazines), there is a new breed of young artists swimming along both sides of this aesthetic picket fence. Pluralism has come to Chicago, and in the process it has knocked the wind out of the regional art history primers.

Three recent salon exhibitions the biennial “Chicago and Vicinity Show” at the Art Institute, “Chicago Prospective” at Navy Pier, and something called “Black Light-Planet Picasso,” held in a day-glo attired loft on the city’s west side heralded the disintegrating dogmas that are shifting Chicago’s fault lines. Post-quake findings indicate that the Imagists, mouth-pieces in place, are waiting for the hell and a chance to punch new contenders senseless.

Chicago as an art metropolis appears ready to shed its regionalist skin. In the process, it must hear up to the strain of microscopic inspections and imperialist attitudes from New York and Europe. What follows is an admittedly subjective scenario of the dangers intrinsic to “second city” thinking.

Young artists flock to Chicago to attend the School of the Art Institute. The school is a high-speed career blender, producing sophisticated, razor-sharp troops for the art market. There is no other institution like it, this side of the Great Lakes. Perhaps in the 1920s and early 1930s the Art Students League in New York provided such a forum for emergent art, but without the important lessons in economics.

Stumbling along this line of reasoning, too many good artists emerge at too young an age in the Windy City. The siren call of New York caresses the inner ear of the New Wave, just like the boulevards of Paris did for the Momentum group thirty years earlier. The result of this “cuisinart” process short-circuits many promising careers in the Second City (so called from national census readings prior to Los Angeles’ takeover). “Second City” mythology persists today and brings on the “Second City Syndrome” that tickles the lips of so many visual artists in Chicago.

What often happens in this stand-by posture of 90-minute air travel between New York and Chicago, or 19 hours speeding on the interstate highways, if you’re transporting art, begins at one of the alternative spaces or co-op galleries that moor the So Ho-ish strip of West Hubbard to the Chicago art scene.

A group show at N.A. M.E. Gallery or Artemesia merits a review in Chicago’s New Art Examiner, an eight-year-old tabloid with a national art audience and a puckish editorial viewpoint. Representation at N. A. M. E. blossoms into a commerical gallery spot on East Ontario Street, a stone’s throw from the MCA. All hell breaks loose after a rotten review in one of the Windy City’s two daily newspapers, the Sun-Times or the Tribune. Although on the editorial pages the dailies are different, the art coverage is strictly neoconservative. The rotten review triggers—on the artist’s part—an intense dislike for everything regional and especially Midwestern. A vacation is planned to New York to visit friends and view the galleries. And so the die is cast.

Simplistic scenarios cannot dent the ravishing veneer of Chicago. Quality is high in the galleries. Professionalism abounds, and no other city in this hemisphere can match the breathtaking loft spaces available. The clean streets and incredible alleyways that give a hack-end view to this handsome metropolis confound visitors from more crowded shores.

The often-heard remark, “it is so much easier living here in Chicago,” is quickly counterpointed by, “but you just have to be able to show your work in New York.”

To round off the jagged impressions from one visitor’s frenzied tour of the Windy City, compressed sketches from a vibrant cross-section of Chicago-based artists follow.

Culled after nine days of riding the wonderous elevated trains that snake along Chicago’s spine, visiting studios, eating in ethnic restaurants, and sipping the beers that at one time made Milwaukee famous, certain hunches stand out. The lion’s share of this pulse-taking deems the patient despite a chronic case of cabin fever in excellent health, strong as a Polish sausage tamale.

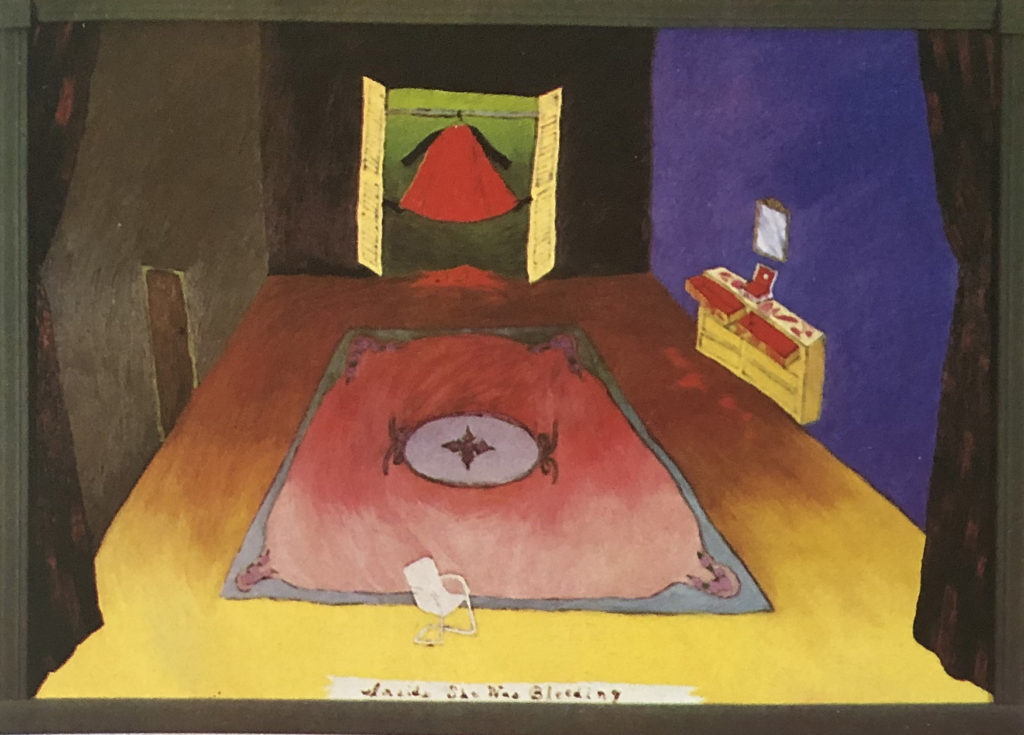

Holis Sigler, “Inside She was Bleeding”, 1981, Courtesy Barbara Gladstone Gallery, New York, Photo D. James Dee

Hollis Sigler

Sipping tea in a tiny booth at a 57th Street coffee shop, her purple leather hag and green corduroy coat spilling onto the formica table top, Sigler discussed the fractured world of living and showing in Chicago while maintaining an equally taxing gallery schedule in New York. Having missed this exponent of narrative art in Chicago, the previous week, a brief interview was arranged while her New York show at Barbara Gladstone’s in the heart of gallery country received last minute cosmetics.

“I wonder a lot about the effects of regionalism. Whether it even exists anymore. Everything is so pluralistic and eclectic in Chicago. I’m an easterner who moved to Chicago. It is a city that has suffered an identity crisis. There are a lot of people who live here in New York and show here but are from Chicago. But they’re not considered Chicago artists. I woke up one day and knew, no matter where I lie, I’ll always he called a Chicago artist.”

Ed Paschke

Paschke’s studio is at the north end of the elevated line separating Chicago from Evanston. The neighborhood is rough and transient, just the kind of “sensibility” that delights this veteran painter of the human condition. “For me it is important to take risks with the paintings. I’m experiencing growth and progress only when I’m doing something for the first time.

“I certainly don’t want to get typecast as a Chicago painter. In late April I’ll open at Galerie Dorthea Speyer in Paris and in June at the Contemporary Art Center in Geneva. But Chicago has been a positive experience for me. I’ve been able to get my work out. It is physically easier to function here, to get things done, to focus, to get plugged into the right network of connections. Most of the artists who leave here and go to New York don’t wind up doing much.”

Phyllis Bramson

Pointing her scarlet-tinted fingernails to a large table resembling an assembly line for a collage-constructionist, Bramson talks about her much-copied style in a breezy and matter-of-fact way. The studio windows (the view and square footage are shared by fellow artist, Susan Michod) reveal the behemoth downtown glass towers, stamped with the unmistakeable signature of Mies van der Rohe.

“There are so many trappings to making art. It’s almost like Kabuki theater. The figure is the first thing I’ll put down. Then I like to abstract the space. I’m going to start making large paintings after I get this stuff the collages—out to a show in New York. I’m interested in seeing Chicago succeed. You don’t have to he necessarily provincial if you live here.”

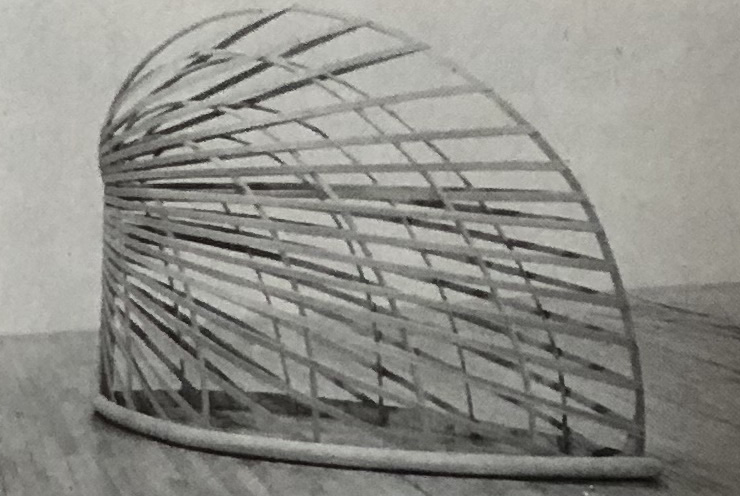

Martin Puryear, “Bower” 1980, Sitka spruce and pine, 64 x 48 x 25 inches, Courtesy Young Hoffman Gallery, Chicago

Martin Puryear

Puryear is a devotee of hand labor, and his studio is studded with a bewildering assortment of wood-working tools. Crouched over a blueprint that takes up much studio floor space, the artist contemplates a landscape design competition for a public square in New Orleans. With his second consecutive representation at the prestigious Whitney Museum Biennial in New York and frequent shows hop-scotching the country, Puryear seems ripe for new directions.

“So far my work has been getting out in a fairly protective context: galleries and museums. 1 feel it’s getting to he time to expand the work, to make it bigger and available to a wider audience without doing violence to the integrity or strength of the ideas behind it. I left Europe after living in Stockholm for a couple of years. I’ve lived in New York. It’s only been since I’ve left New York that I’ve gotten visibility and my work has been circulating. I’m just an artist who happens to he living right now in Chicago. I find it a real civilizing place to work.”

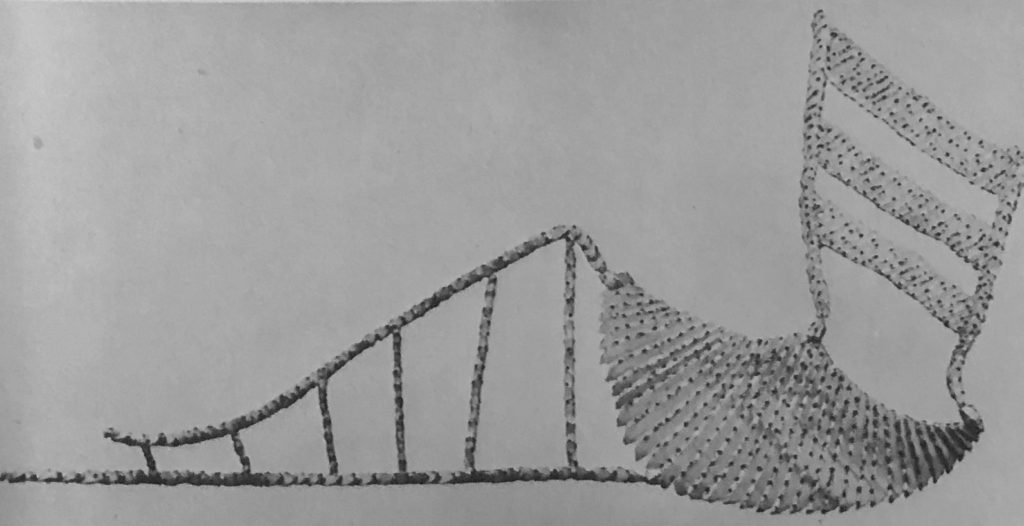

Margaret Wharton, “Odalisque”, 1980, 51 x 99 inches

Margaret Wharton

Balancing a thick binder of color slides and the long ash of a cigarette en route to the gallery’s slide projector, Wharton projects a serious vein of introspection laced with a sharp and subtle humor. If you came out to see me in the suburbs and my little garage and my children, you might get confused and think I am a housewife. I’ve lived in Chicago for ten years. I think of myself as a recluse. I don’t think of myself as mainstream. I’m off on some little twig. From my standpoint, everybody has a different perception so when somebody comes up to one of the chair pieces in the gallery and asks, “what the hell is it’?” I have a one word title for it. I’m interested in people appreciating the fact that the sculpture is a chair.”

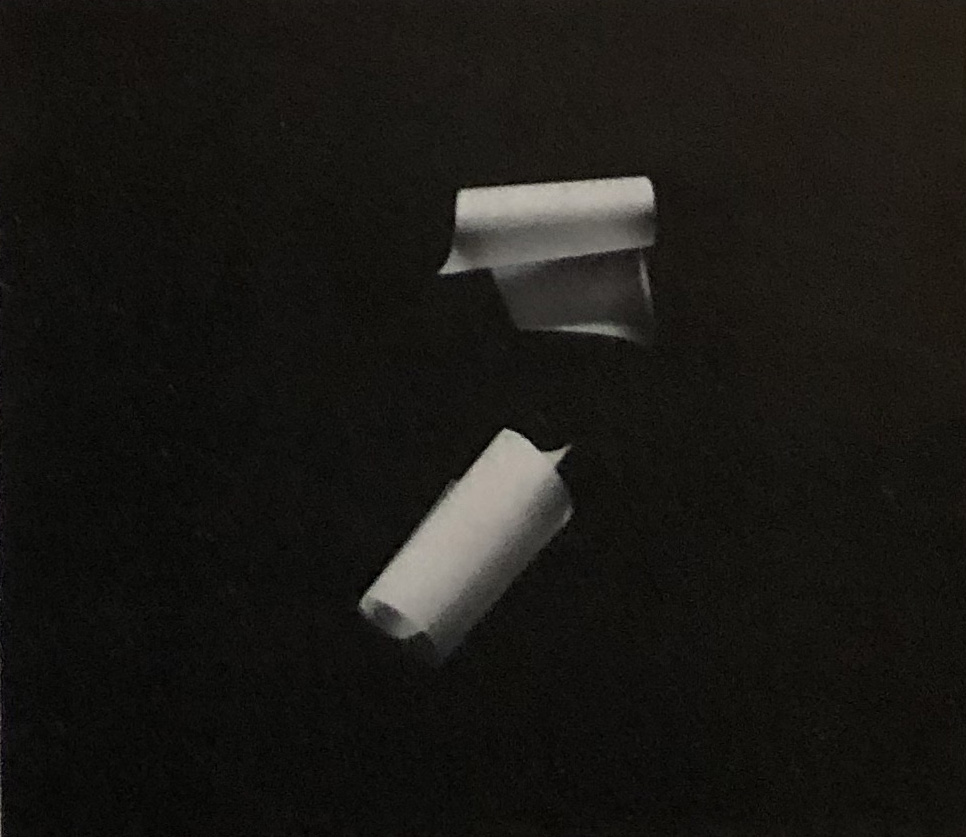

Thomas Kovachevich, “Trapezoid Duet”, paper on fabric, 24 x 11 inches, Courtesy Betsy Rosenfield, Chicago

Tom Kovachevich

After a hypnotic demonstration in his darkened studio (illuminated only by the thin beam of a klieg light) of cut-out tracing-paper circles, triangles and squares performing hackflips and cartwheels on a black field of partially submerged polyester fabric, the one-man audience was tho- roughly tongue-tied. A visual artist who breaks up his studio time with a private medical practice is as unique as his accidental discovery and plastic-arts application of a physics phenomenon.

“The work has been criticized as too educational, that it is derogatory to explain how it was done. The process is as legitimate as the product. It sounds pretentious to just hear about it, it even sounds crazy. But it’s an unexpected phenomenon. It would he like seeing paint peel off your living room wall. It is impossible to isolate art. You have to compete with science. In my work, I’m the agent, producer, director and lighting man.”

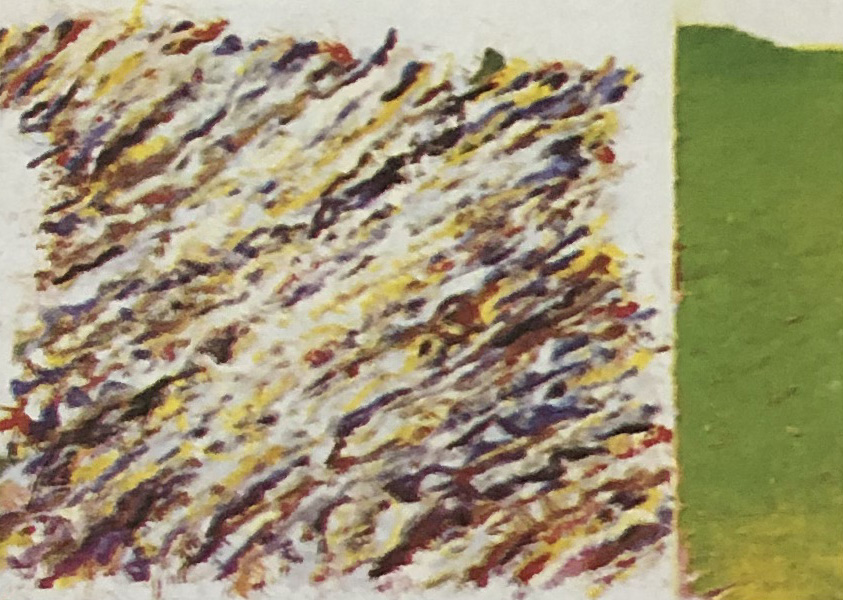

Nina Beall, “Landscape with Corn Stacks”, 1980, Acrylic on canvas, 52 x 57 inches, Courtesy Frumkin-Struve Gallery, Chicago

Nina Beall

Speaking with the lilting twang of eastern Texas, Beall described the origins of her striking acrylic landscapes and their reception in the big city. Applying paint with a bevy of cake decorator tools, the canvases weigh in at ninety pounds, causing great consternation in the halls of the School of the Art Institute. One critic described the work as if “Van Gogh had cut off both ears.” Recovering from her first solo show in Chicago, Beall already has gallery representation in New York.

Mike Zieve, Battalion Linda, 1980, Acrylic on masonite, 4 x 3 feet, Courtesy Nancy Lurie Gallery, Chicago

Michael Zieve

Zieve’s ramshackle apartment (he paints in the “dining room”) on the city’s west side is crammed with kitschy objects and an afficionado’s stack of rock’n’roll records. Raving about his favorite neighborhood gang, “The Almighty Insane Unknowns,” the 27-year-old painter exudes a zany enthusiasm for Chicago. “You don’t have to deal with seeing a million artists every day on the streets like you do in Manhattan. It’s like living in Brooklyn. The worst thing is that Chicago has that Second City image. We are second. Nothing can come directly here. God forbid, an artist should move here (like I did). Only art students move here to go to the Art Institute. I’ll always wish it were different. This coming June I’ll he in Europe showing at the Center for Contemporary Art in Geneva, so I’m real excited. I’ve never been to Europe before.”

Vera Klement, “Witness”, 1980, Courtesy Marianne Deson Gallery, Chicago. Photo Lisa Claffey

Vera Klement

Located due south of the massive landmark, the Monadnock Building (designed by John Wellborn Root in the 1890s), Klement’s studio, in the heart of “Printer’ Row,” is as sleek as her large encaustic canvases. On the eve of departure for Europe, the mover-shaker of the Chicago abstract movement known as “The Five” in the dark ages of the mid-1970s, paced nervously, tailed in detective fiction style by her long- haired cat, Deen-Du.

“The minute the gesture hits the canvas, it sets. That’s the beeswax part of the paint mixture. The surface stays malleable for a day or two so you can score it with a brush and knife. The texture is creamy, runny and delicious. The paintings are divided and work in tension with one another. One section is calm, distant and spatial. The other has an immediacy, a spontaneity, an anguish.

“With a gallery representing you there is a tension to keep your style going. You need as an artist—the nerve to veer off the center.”

Seymour Rosofsky

Having shown more in Europe (at Galrie Du Dragon in Paris and Odyssia in Rome) than his home town of Chicago, it was enlightening to hear the 57-year-old painter wax ecstatic over crumbling neighborhoods between bites of pancakes and eggs in his favorite coffeeshop, Rayan’s Two-Way Restaurant. A week following this breakfast, Rosofsky was shaking hands and sipping white wine at his first one-man show at Monique Knowlton’s Madison Avenue Gallery in Manhattan.

“I’m a Chicago artist. It’s one world. like regionalism. When I go to China want to see Chinese art. Provincial isn’t the word. I find the very ordinary, everyday places—like this coffeeshop here–very exciting. I like the run-down, old-world quality of Chicago. Like James Joyce’s Ulysses, you can see the “floatsam-jetsam” of people’s lives, walking through the alleys and riding the elevated.”

Jim Brinsfield

Sharing a large studio with Darinka Novitovic, the artist-couple mounted the much-talked-about “Black Light-Planet Picasso” show. The prematurely gray and gangly expressionist was quick to kidnap his guest to a friend’s studio in order to view John T. Phillips’s massive painting, Humbert’s Dilemma. Roaring west on Division in a heat-up Gremlin coupe, Brinsfield suddenly pulled to the curb and shouted joyfully that a body was lying in the middle of the avenue. Luckily, it turned out to he a high-heeled and hewigged dummy, strategically placed by neighbor- hood pranksters. Somehow, this black-humored prank seemed perfect for the driver’s manifesto.

“In Chicago, the galleries will wait for New York approval first. They’re not interested in stepping out of their place. There’s room for more galleries here. There’s a new generation of artists just waiting to he plucked.”