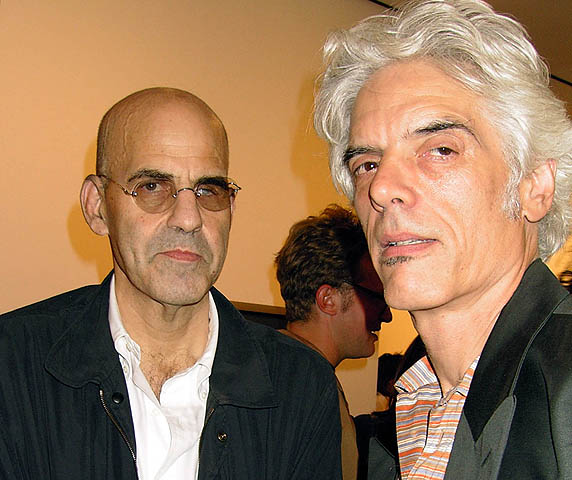

The late & great Art + Auction editor-in-chief Bruce Wolmer with Tully at some art world event. Undated but pre-2007.

I started out writing art reviews for Flash Art and Arts in the 1980s in New York. At the time I’d go to the Museum of Modern Art library to do research, and someone who worked there, who had noticed an art market story I’d written, said, “The Washington Post is looking for a stringer” and put me in touch. The Post sent me to report on an American-paintings sale at Sotheby’s — I don’t think I’d ever been there.

The editor told me that the National Gallery, in Washington, was intending to buy Rembrandt Peales portrait Rubens Peale with a Geranium, [1801], and that the museum’s director, J. Carter Brown, was going to be there, and I should interview him if he bid. Brown bought the painting for a record price [$4,070,000], which was big news in D.C. So my first story for the paper ended up on the front page.

I covered the New York market for the Post beginning in the mid ’80s, when the market was starting to go up. The auction houses were getting more publicity with sales of $40 million van Goghs. I think galleries were feeling left behind, and they started launching art fairs as counterweights to the auction spectacle, which it really was. The totals accelerated with the arrival of Japanese buyers, and that also drew a lot of media attention. In the salesrooms, there would be two rows of Japanese in dark suits, and guys you’d never heard of would come with their own video crews filming them at auction. No one then had a clue what this massive buying was about, but it later became clear that it was an elaborate money-laundering operation for Japanese businesses to hide profits. Recently, people speak with surprise about how Russian buyers accounted for a quarter of purchases in a single sale. But the Japanese accounted for 40 percent of Imp/mod auction purchases for a number of seasons. When they disappeared, they killed a large segment of that market.

A story that was truly stranger than fiction was that of the art dealer Michel Cohen, who bilked collectors and the houses out of millions — he owed Sotheby’s $10 million — then vanished. Later he was arrested in Brazil and imprisoned, but he managed to escape by pretending to be sick and fleeing the ambulance. I started talking to prominent people who had been affected, but no one wanted to admit to being conned. They would tell me what a great guy Cohen was, that they didn’t understand what happened, or why, when he promised to send $3 million by wire transfer, the money never came.

I’ve talked to a lot of dealers over the years and have become friends with some of them, and we have discussions about artists and the business, but owning a gallery is the most bewildering activity. I don’t know what art dealers really do. They sit around in nice suits and take calls. How do they do it? What occupies them?

When you’re a journalist, there’s a divide between you and whomever you’re talking to. A lot of collectors are superwealthy, and there’s no similarity between your station and theirs. The only reason you’re sitting in their living room is because you’re writing something. You do get a certain access, but I think journalists are generally regarded as pretty low in the pecking order. It’s not that you can’t be friendly. My favorite collector whom I met and profiled was Richard Brown Baker, who died in 2002. He went to Yale and worked in intelligence during World War II. After the war he came to New York to be a novelist, and he started to go to galleries and buy art. I’d see him at auctions in the ’80s. When Roy Lichtensteins Torpedo … Los! sold for $5.5 million in 1989, he said, chuckling, “I got my Lichtenstein for $5,000 from Leo Castelli.”

The art world is small but very secretive. Sometimes it’s hard to get the real story. It’s only once a situation gets to the lawsuit stage, when there are papers documenting what one side is charging against the other, that you ever see it in black and white. And that’s a pleasure, in a way, but most of the time it isn’t that clear-cut.

Judd Tully is editor at large of Art+Auction. He has been contributing to the magazine for 21 years.