There’s a great deal of good humor when he sets his merry-go-round world spinning—but there are needles and sharp edges, too

When Red Grooms—caked in whiteface—tumbled backward out of his Burning Building set in December 1959 onto the creaky floor of his Delancey Street Museum, the cagey New York art world sat up and took notice.

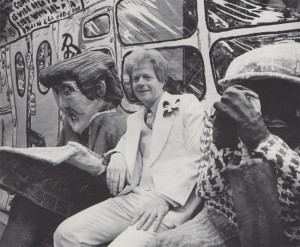

Red Grooms seated between passengers on his “Subway” at the May 1976 opening of “Ruckus Manhattan”. Photograph by John Cornell; ©1976 Newsday Inc.

The fresh-faced 22-year-old with the shock of carrot-colored hair combined theater, circus and brash expressionist painting, creating one of the first Happenings that in many ways signaled the end of the formidable Abstract Expressionist epoch and the beginnings of what became known as Pop Art.

This month in Philadelphia, at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, audiences will have their first chance to see 29 years of his work in Grooms’ first major retrospective. The show has been supported by the Atlantic Richfield Foundation.

A master of many media, Grooms’ sprawling exhibition of 170 objects will show not only painting, sculpture, prints and drawings but a skyline of towering “sculpto-pictoramas” from The City of Chicago to the dragon-dad Woolworth Building in Ruckus Manhattan. The artist’s considerable film oeuvre will be screened behind the elaborate Tit’s Fever marquee, a sneak preview of his portable movie palace still in the design stage.

The itinerary for the traveling retrospective, after it departs Philadelphia in late September, includes the Denver Art Museum (November 2 through January 5, 1986), the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles (March 12 through June 29, 1986) and back to the artist’s mots in Nashville at the Tennessee State Museum, where it runs from August 17 through October 26, 1986.

Three months before the exhibition, which opens on the 21st of this month, I visited Red Grooms late one afternoon in his Manhattan studio a block away from the main drag of Chinatown. He greeted me at the door, introduced Tangra, his Tibetan terrier, and placed a cold can of beer in my hand before I could get my notebook out. Backpedaling to the dining table he picked up a brush and quickly dispatched some gouache over a lithograph titled Loma Doone. Leaning over the table, painting and talking, he could just as easily have been shining shoes. He apologized for the slight delay, gesturing to the grinning, leopard-skinned lady sprawled on a wheatfield (in a pose that was disturbingly reminiscent of Andrew Wyeth’s Christina’s World): “I’ve got to send her out tomorrow.”

Leaving Lorna Doone to dry, we repaired to the living room. I wanted to know how Grooms felt, with the approaching triad of retrospective, Carter Raclin Abbeville Press coffee-table monograph and the museum’s own hefty catalog. “It’s staggering and numbing but it hasn’t been an overnight thing. The retrospective,” he continued, “has been in the works for two years and the Abbeville book for at least four, so there’s been a spread of like five years with this calamity coming down on me in junior middle age, like a TV episode of This is Your Life.”

Looking at Grooms it’s hard to believe he’s pushing 48. Stretched out in a leather-and-chrome Wassily chair, one long paint-spattered jeans leg crossed over the other, his flannel shirt and wool lumber jacket buttoned up to ward off the loft’s chill, he filled the air with his Tennessee twang.

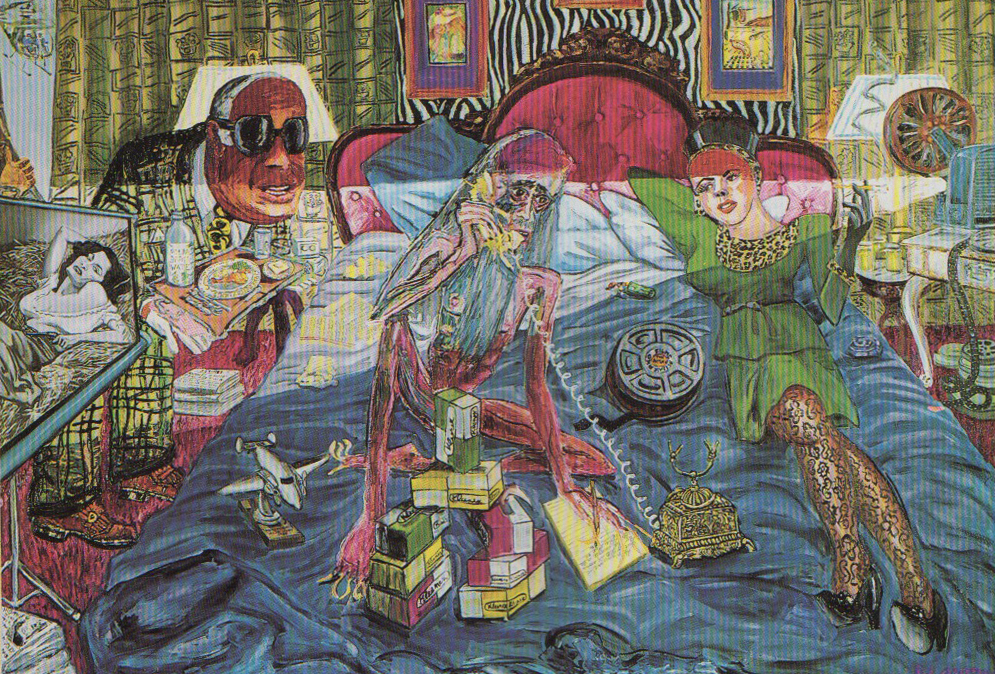

Nightmarish montage on last days of the recluse Howard Hughes (not in show) is entitled The Tycoon. To set scene, Grooms hired an Atlantic City hotel suite, posed filmmaker Rudy Burckhardt as Hughes.

I was curious about his range in subject and style, from watercolor landscapes of Caribbean isles to Manhattan cityscapes gridlocked with bizarre bag ladies and purple-coifed punksters; from the small intimate portraits recalling the calm bourgeois interiors of Vuil-lard to a life-size replica of a grungy Manhattan subway car, lurching on truck springs and peopled with a cast of plaster figures that rivals the gruesome stories in the pages of the New York Post.

“It’s very confusing where my taste for this academic painting comes from, but I’ve always had it and it runs counter to my burlesque style. I guess they’re just two sides of a coin. Those are the two things I really like—either completely burlesque or just very controlled.” What the artist calls burlesque is a highly sophisticated form of theater. He is in the truest sense an action painter.

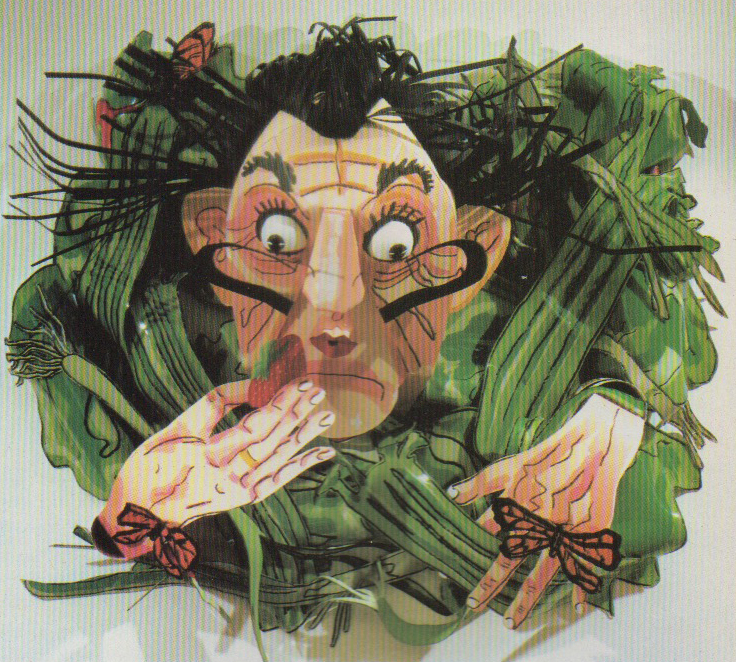

Grooms has painted and constructed a series of portraits of artists who fascinate him, here of famed surrealist Salvador Dali in mutation, titled Dali Salad, 1980-81.

Two paintings from the retrospective illustrate this dichotomy of style. Don’t Walk (1963) is a traffic planner’s nightmare; pedestrians jam the foreground with a queasy assault of long strides and clashing textures of jackets, shoes, hats and handbags. The city dwellers walk like robots, impervious to the clotted traffic wait-ing to bear down on them from the crosstown street. Traffic lights blink, cops scowl and a crowbar couldn’t pry one more figure into the scene. An anthropologist could pick at the painting for cultural clues. The breathless style, the jabbing caricature of New York’s frumpiest, recalls the quick draw pen of Honore Daumier and his 19th-century spectacles of Parisian theaters, salons and street life. Daumier too became a sculptor, as if the scratchy lined technique was not enough to satiate his appetite for details. Daumier painted his clay sculptures, distorting features to the edge of bad taste. Grooms jumped—as Daumier did—to the third dimension.

Kids Watching Me Paint (1961) has an ethereal air, far removed from the anarchy of Don’t Walk. A cerebral notion informs the canvas, painted with a smooth, soft realism on a bank of the Arno in Florence. Intent on capturing the beautiful green hills framing the city, Grooms noticed a bunch of young spectators watching him work. Inspired, he turned the canvas around to paint their faces blushing in the landscape. “In the moment of being on holiday I could indulge in that particular taste I had for the naturalistic,” says Grooms. “The curator has done a good job interweaving that stuff in with the buildup of the big pieces.” While working in this traditional, academic form, Grooms can’t restrain his intuitive impulse, painting a kind of play within a play. Mischievous spontaneity is the touchstone of his style

Pennsylvania Academy curator Judith E. Stein has organized the exhibition around specific themes that have obsessed Grooms since the 1950s. It includes city life, art about artists, global politics, sports, portraits of friends and family and a cavalcade of self-portraits in a diverse range of media. According to Grooms, theme has been a key to his work, the one thing that keeps him in line. “Outside of it,” predicts Grooms, “my work would be overly spontaneous if I didn’t force it to stick with certain themes. You can make ‘stuff but you’re only given a certain amount of inspiration and it has always been critical for me to tie that to a pertinent subject. The city theme, for instance, sometimes takes a backseat to the personal thing; the experience of traveling, to go to new places, has been a big influence.”

Since his boyhood in the suburbs of Nashville, Grooms has had a hankering for travel, fueled by the nomadic carnivals and circuses that trooped through Nashville’s state fairground. An ad in American Artist magazine for the Famous Artists School in far-off Connecticut lured him to subscribe to a correspondence course in commercial art: “We’re looking for people who like to drawl .. Let our Talent Test…” the ad implored. But he soon tired of his assignments being returned first-class with the red-penciled corrections obliterating his original work.

Grooms saw Jackson Pollock’s Sleeping Effort in Nashville’s cavernous Parthenon (a full-size replica of the Athenian temple). This late masterpiece was part of “A Collector’s Choice,” a traveling exhibition organized and circulated by the American Federation of Arts. For Grooms it was an epiphany. At this point he decided to pursue “fine art.”

He left Nashville for Chicago and the School of the Art Institute shortly after his high school graduation in 1955. He’d already had a successful two-man show with his friend Walter Knestrick at Nashville’s Lyzon Art Gallery, which doubled as a frame shop where Grooms worked part-time.

Although bewitched by Chicago’s skyline, his brush with the school was a fiasco. He quit after two and a half months and returned home, only to leave again for New York and a painting clan at the New School for Social Research. Again be was bewitched by metropolis and disappointed with school. “I really didn’t want robe told what to do,” Grooms would tell an in-terviewer years later. It was back to Nashville, a restless year spent at a teachers’ college and a third try up north to Provincetown on Cape Cod and the esteemed Hans Hofmann school (his mother had read about it in Time magazine). Grooms dropped out again, but this time he had stuck around long enough to be swept away by the art scene.

Those early impressions of city life, of architecture and bridges, of anonymous faces rushing to unknown destinations, were gathered in little notebooks, marinating over time into the 3-D “novels” of City of Chicago and Ruckus Manhattan. Whether it be Paris or Cairo, Grooms has a genius for capturing the texture and mood of a particular place, peeling away layers to reveal the soul of the city.

It is now 1957. The Beats are in. Jack Kerouac’s On the Road and Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl” are underground best-sellers. Action Painting is the new religion. American cars sprout tail fins and chevrons of chrome. The Cold War dominates the news while cool jazz and poetry waft through the cafes and smoky nightclubs. The traveler Grooms falls in love with the bohemian scene.

Cooperative galleries sprang up in the downtown streets of Manhattan. They were dedicated to showing an alternative to the Abstract Expressionists (de Kooning, Guston, Kline and Pollock) who dominated 57th Street and made New York the world capital of contemporary art. Grooms gravitated to East 10th Street and the company of Lester Johnson, Allan Kaprow, Alex Katz, Jan Muller, George Segal, Lucas Samaras and Bob Whitman, all of whom pursued styles diametrically opposed to abstraction.

In the three years Grooms traversed the New York-Provincetown art circuit—a time as breathless as the unedited prose of Jack Kerouac—he opened City Gallery with his friend Jay Milder, exhibited two unknowns, Claes Oldenburg and Jim Dine, and captured the fancy of art-world enfant terrible Robert Rauschenberg and the polished art critic and painter Fairfield Porter. Just as art-magazine reviews of Grooms’ ten minute performances and thick-crusted paintings trickled in, he shuttered his second gallery, the Delancey Street Museum, and hung up his Happening hat. Though the time seemed ripe for success, he packed up for Paris. (Sixteen years later, feted by the city and showered by the confetti of rave reviews for his sculpto-pictorama Ruckus Manhattan—which he and his wife Mimi built with young artist helpers—Red would flee the limelight again for the anonymity of Paris.)

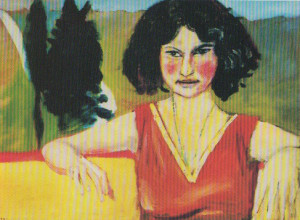

After great success in New York, Grooms left for Italy and painted portrait of wife-to-be Mimi, 1961. Collection Paul Suttman, Brooklyn

As in most first landings, his initial brush with the Continent was bumpy. A short spell in a Parisian jail following a fracas outside the call La Coupole hastened Grooms’ exit to the friendlier climes of Florence where his friends Mimi Gross and Katherine Kean lived the lives of artist-expatriates. Via Guelf a Studio (1961), with its cast of floating figures, captures the liberated artistic spirit.

A homemade picture postcard from Kean’s press shows Red and Mimi sketching the lush landscape of a Tuscan hillside. Parked at their side, a hone-drawn carriage, hand-painted from roof rack to spoked wheels, announced from the drop-cloths at its sides, “II Piccolo Circo d’Ombra di Firenze” (The Little Shadow Circus of Florence). For eight weeks the barefoot group of expatriates toured the hill towns of Northern Italy, performing at dusk with Mimi’s hand-shadow puppets, and drank in the sights and sounds of Renaissance art. The horse was christened Ruckus.

The picture of Red and Mimi sketching within whispering distance would be repeated in an endless carousel of images in an endless variety of media over a 15-year relationship that would take them back to New York with sorties to Chicago, Minneapolis, Cape Canaveral and Fort Worth. The sounds of Ruckus’ clippety-clops changed into a cacophony of hammers, saws and drills. The artistic racket retained the name of Ruckus, the metaphor for Grooms’ walk-in environments. The puppets the young couple manipulated to the delight of tiny audiences in Italy would evolve into larger-than-life-size figures occupying worlds as strange and exciting as those first sights of Bernini’s and Brunelleschi’s wondrous buildings.

Artists, actors, friends, collaborators

For Grooms the canvas has never been big enough. Film and animation have enabled him to visualize his spectacular notions, making him a kind of D. W Griffith, the famed director who in 1916 shot Intolerance and built a half-mile-long set to accommodate 5,000 extras. Out of Grooms’ early experiments of home movies that kept growing, and from his casting artist-friends as actors and collaborators, evolved the sculpto-pictoramas of City of Chicago (1968), The Discount Store (1970-71), Astronauts on the Moon (1972), Ruckus Manhattan (1975), Ruckus Rodeo (1976), The Bookstore (1979), Welcome to Cleveland (1982) and Philadelphia Cornucopia (1982).

With his first collaborator in 16mm celluloid, the filmmaker and painter Rudy Burckhardt, Red made Shoot the Moon in 1962, a project tackled after his and Mimi’s Italian sojourn. The 24-minute film was a poetic homage to the French trailblazer of cinema, Georges Wills, and his 1902 Rip to the Moon. The papier-mache comet was baked in Rudy’s oven.

Last year, Burckhardt stoned in an unusual Grooms production that required a lavish trip to Atlantic City. Grooms rented a two-bedroom hotel suite, covered the bed with boxes of Kleenex, yellow legal pads, pills and telephones and had the dapper 71-year-old Rudy strip down to his skivvies to pose as the reclusive Howard Hughes. The culmination: an extravagant painting entitled The Tycoon.

The “germophobic” Hughes is trapped in a culture he helped create. The aerospace titan sits on his bed, illuminated by the beam of the movie projector frozen on a close-up of Jane Russell. His empire is reduced to a hotel bedroom. Grooms loads all of the media stories about Hughes onto his brush and comes up with a portrait that captures the myth of the modern American hero.

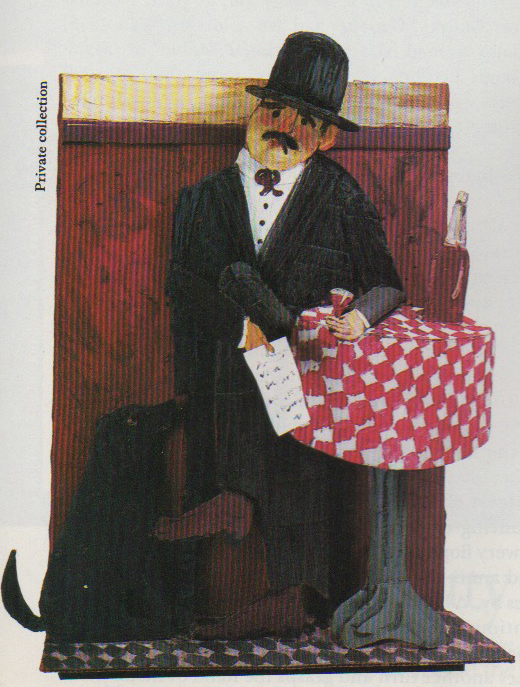

Poet Guillaume Apollinaire, a major figure in Paris art circles, is appropriately pictured in a cafe.

On the heels of Shoot the Moon, Grooms had his first one-man show in two years at the Tibor de Nagy Gallery in 1963 (he’d had one in 1960 at the Reuben Gallery). Featured in 1963 and part of the current retrospective is a multimedia, cutout-figure tableau, Le Banquet pour le Douanier Rousseau. It celebrates the legendary dinner held in 1908 for the eccentric Rouueau in Picasso’s own studio in the artists’ build-ing in Montmartre dubbed bateau-lavoir (laundry barge) by Surrealist poet Max Jacob. Among the guests at this avant.garde “last supper” were Gertrude and Leo Stein, Alice B. Toklas, Apollinaire, Georges Braque, Max Jacob, Lolo (a pet donkey) and a score of other luminaries of the Parisian art scene.

In 12 years at Tibor de Nagy and at John Bernard Myers Gallery, Grooms had ten solo shows. In 1975, Grooms joined the international stable of Marl. borough Gallery. A year later, more than 100,000 viewers would troop through Red and Mimi Grooms’ “sculptural novel” Ruckus Manhattan.

More than meets the eye

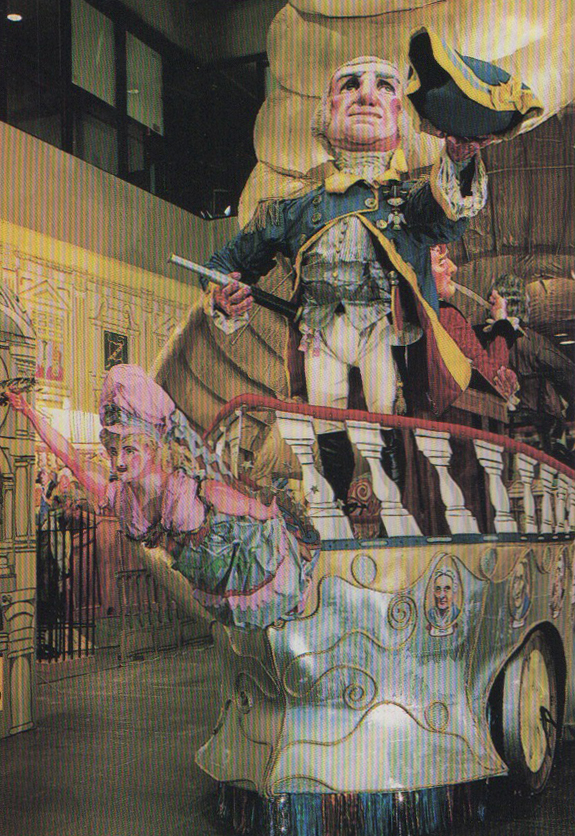

Martha is figurehead, George commands American Ship of State in Philadelphia Cornucopia, 1982.

For all of the lighthearted banter, Grooms’ deadly accurate eye—even when it focuses in front of fun house mirrors—has created a profound impression of contemporary life. Flipping back through the pages of American art history, no member of any school, from Ashcan to Social Realist and up through Pop and Environmental Art, has captured the soulful fabric of the city with the force Red Grooms has.

Part of that power is journalistic. Grooms is the man on the scene, recording the moment as he sees it, as writer Stephen Crane did with his New York City Sketches of the late 19th century. Crane’s vivid style, pouncing on artists’ garrets, gamblers and con men, Bowery flophouses and Chinatown opium dens, delivered a mix of sympathy and irony, two traits Grooms lives by. While Grooms’ ongoing chronicle of the street continues in the great American tradition of John Sloan, Reginald Marsh and Weegee the Famous, he takes another turn and grasps the hand of history.

Grooms is no stranger to Philadelphia. His sculpto-pictorama of that city, Philadelphia Cornucopia, has resided at the city’s Visitor Center since March 1983 after a dazzling run at the Institute of Contemporary Art. Grooms packed 200 years of history into an out-rageous ship of state that ferries the likes of Benjamin Franklin, George Washington and a plush-robed Thomas Jefferson chewing on the tip of a quill pen while composing his Declaration. A Martha Washing-ton figurehead guides the prow of the ship as her hus-band, the General, doffs his tricorne from the forward deck. Nearby, the piercing eyes of architect Frank Furness, the genius behind the Pennsylvania Acad-emy’s grand exterior and polychromed interior, sur-vey a life class run by Thomas Eakins—an event, by she way, that got Eakins booted out of the Academy for having a nude male model pose for the segregated women’s painting class. That is another story, one of the hundreds spun by Grooms’ unquenchable thirst for detail, what he calls a chronic case of horror vacui.

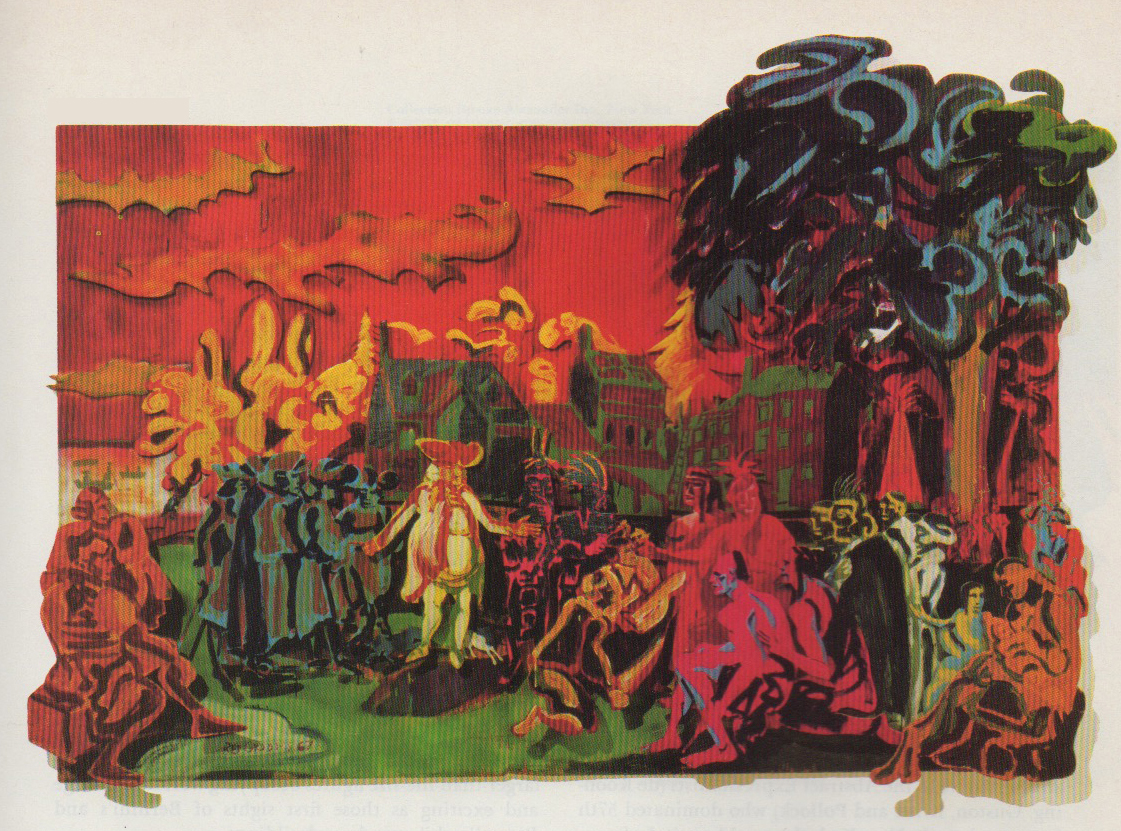

Benjamin West’s painting, Penn’s Treaty with the Indians, 1771, is a classic American landmark. Courtesy Pennsylvania Museum of Fine Arts.

One of the finest paintings in the Academy’s permanent collection is Benjamin West’s Penn’s ‘Reaty with the Indians (1771). Grooms, inspired by West’s ambitious narrative, tried his hand at depicting the same event in 1967. Grooms’ version, William Penn Shaking Hands with the Indians, mimes West’s. According to Grooms, West painted the large-scale scene on his estate, while standing in a balloon contraption tethered 60 feet in the air. His wife stood by at ground level, keeping him supplied with sandwiches and birch beer during the six-day marathon. The models were recruited from a touring Shakespeare company. Mew. en in Philadelphia will have the unusual opportunity of comparing the paintings.

Red Grooms, “William Penn Shaking Hands with the Indians”, Courtesy Denver Museum of Art

Grooms did another takeoff—this time on Edward Hopper’s classic Nighthawks (1942), his version en-titled Nighthawks Revisited. While Hopper creates shadowless isolation outside a window of coffee-shop light, Grooms injects prowling tomcats and a passing car. Hopper sits at the curved counter over a mug of steaming coffee. Grooms steps into the picture depict-ing himself as the white-jacketed counterman bowing to the icon of realism.

A Room in Connecticut (1984) is the latest painting in the retrospective. Art detective Grooms is in his finest form, taking us, as Edward R. Murrow used to do, into the living rooms of famous people. Marcel Duchamp is seated next to his patron Katherine Dreier, the legendary American collector of avant-garde art. Duchamp’s Dada sculpture, The Large Glass, looms in 3-D in the foreground (the original is in the Philadelphia Museum of Art, part of the Arenberg Collec-tion). When I asked Grooms about the scene, he said, “I just liked the personalities and the crazy juxtaposition between the avant-garde work and the fuddy-duddy atmosphere.”

David Saunders is a 30-year-old New York artist who has worked with Grooms on many a Ruckus and edited a number of his films. “I come back again and again,” Saunders said, “to working with Red Grooms. I think our natural tendency is to seek order and we sometimes forget the importance of intuition in our lives. There’s no better reminder than to share in Red Grooms’ creative process. Working with him is more than executing a preconceived idea: it is a continuous process of inspiration. He can precipitate the kind of lucky accident that to most artists is a precious rarity.”

Just as the curator, registrar and team of consulting architects put the final touches on the show’s organization, word came from New York that Grooms wanted to forge ahead and build his list’s Fever environment in time for the Philadelphia opening. Nerves began to frazzle. Back in his studio, Grooms adds another figure to his movie-palace marquette, resembling a lavish production number of Hollywood Meets the Nile. The irrepressible showman lacks only funds to build his palace. He has the use of a cavernous studio across the river in Astoria, Queens, on the old Paramount Pictures location where Valentino, the Gish sisters, Gloria Swanson and D. W Griffith worked. Grooms stands over his doll-house-size model, reaching in to lift James Dean out of a custom-fitted sarcophagus worthy of Tutankhamen. Red laughs and waves the miniature movie star. With a gleam in his blue eyes, he tells me of plans for Tut in a proposed museum at the Paramount site once the retrospective ends.

Now, with his deadline extended to the breaking point and fund-raising efforts exhausted, Grooms must delay construction of his lavish movie palace. His vision of a goldleafed Sphinx sailing over the heads of the audience seated inside Tut’s Fever will have to wait. The illuminated marquee will be installed in Philadelphia but the rest of his Egyptian cast hopes for a debut later in the itinerary of the show, in Los Angeles. Red’s reverie repeats in a stage whisper, “My head is swimming with the possibilities.”