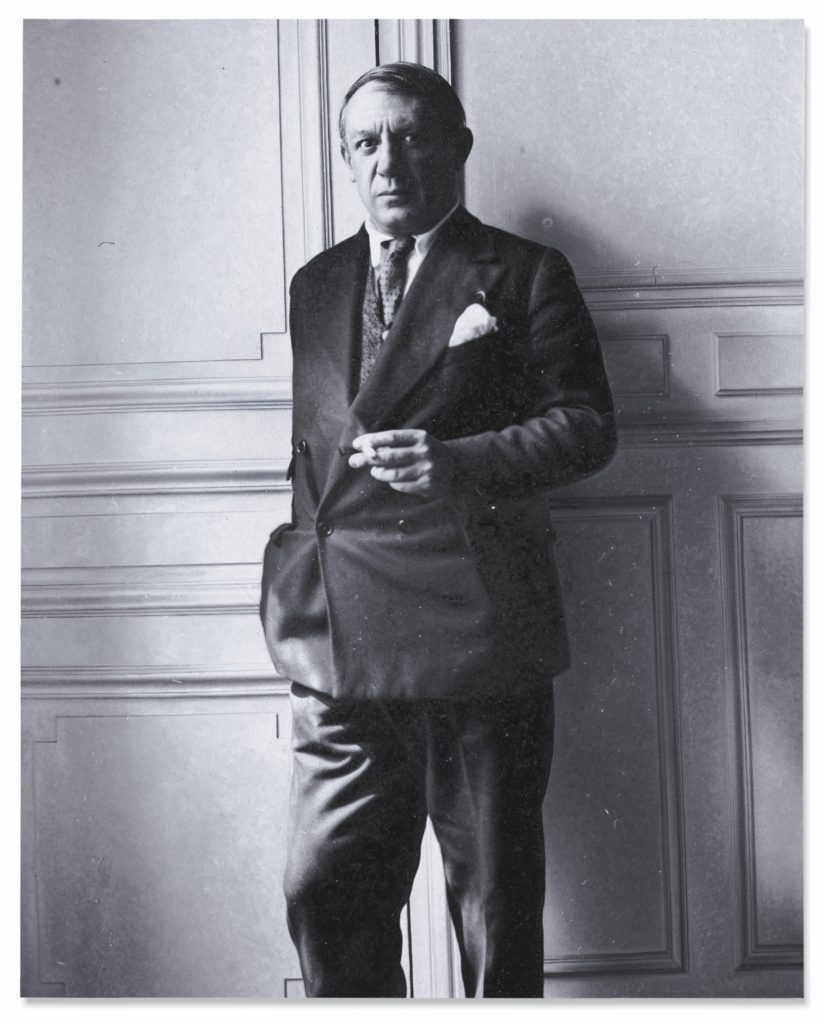

Rudolf Stingel, Untitled, 2012.

©2019 CHRISTIE’S IMAGING LTD.

Rudolf Stingel’s 2012 painting Untitled, which sold at Christie’s New York this past May for $6.5 million but has not been paid for in full, remains under lock and key at the auction house while a battle over its ownership unfolds in the Supreme Court of the State of New York. Today, one of the vying parties filed a fresh memorandum of law that further unpacks the murky nature of who exactly holds clear title to the painting.

The selling agent behind the disputed painting, a 95-by-76-inch blow-up of a 1930 black-and-white photograph of Pablo Picasso elegantly outfitted in a double-breasted suit and tie, and smoking a cigarette, was the 32-year-old art dealer Inigo Philbrick, the subject of several lawsuits in three jurisdictions amid allegations of a massive art fraud some experts peg in the $100 million range.

What today’s memorandum makes clear is that the case revolves around a transaction that looks like a purchase, but in fact represents a loan made to Philbrick. As attorney Judd Grossman put it, “That is the real story here of what is going on with all of these Inigo deals—there was a lot of easy money allowing him to perpetrate these frauds, not only from the Reubens but others as well.”

The Reubens would be Guzzini Properties Limited, an entity registered in the British Virgin Islands that is a subsidiary of the Geneva-based Reuben Brothers SA. Guzzini claims to be the rightful owner of the Stingel, along with Wade Guyton’s Untitled from 2006 and Christopher Wool’s Untitled enamel on linen painting from 2009, having acquired the trio of works from Inigo Philbrick in June 2017 for $6 million.

The sale and purchase agreement under the Guzzini Properties Limited letterhead is described as a “finance document,” which in English law, the governing law of the Guzzini document, covers financial obligations to a lender or other secured party. It lists the works’ respective values in this way: $10 million for the Stingel, $6 million for the Guyton, and $9 million for the Wool, all told, $25 million worth of canvas.

In the memorandum of law filed today by Grossman, the attorney representing “for parties in interest” Aleksandar Pesko and Satfinance Investment Ltd., another entity vying for title, states in part, “Although Plaintiff here (that’s Guzzini) alleges that the total “purchase price” for the Stingel and two other artworks was $6 million, according to the loan agreement, the total value of the three works is actually closer to $25 million…. These figures are more in line with the typical loan-to-value ratio for art-backed loans, rather than the alleged “purchase price” for artwork in a purported arm’s length, non-distressed sale, as Guzzini claims was the case here.”

Today’s memorandum includes several exhibits, among them an email written by Pesko in October to Lisa Reuben, the daughter of the multibillionaire Simon Reuben and a former executive in Sotheby’s contemporary art department, and apparently the point person in the Guzzini matter.

Pesko attached to the email the invoice and payment proof of $3.35 million in January 2016 to Philbrick for a 50 percent share in the Stingel.

Efforts to reach Reuben by email went unanswered, as were phone and email requests for comment from Guzzini’s attorney, Wendy Lindstrom of Mazzola Lindstrom.

If the competing claims over title of the Stingel in the Supreme Court of New York matter sounds complicated, the picture is further tested by a separate action in the Circuit Court of Miami-Dade County where the German entity FAP GmbH (Fine Art Partners) alleges it acquired the same Stingel from Philbrick in 2015 for $7.1 million.

FAP filed its complaint in October in Miami, where Philbrick maintained an eponymous gallery, which abruptly shut down shortly after the FAP filing.

In the Guzzini sale and purchase agreement, revealed for the first time today, Philbrick, the seller, had a buy-back option on the three artworks for a fee of $10,000 and a stipulation that the buyer (Guzzini) “undertakes not to sell the Artworks until any option for the Seller to buy back the Artworks expires.” That expiration date was August 2019, three months after the Christie’s non-sale.

The Guzzini agreement was provided to Grossman, Pesko’s counsel, by Philbrick before he went missing sometime in November.

Adding to the confusing drama of the battle over the sequestered painting, Guzzini’s action for winning clear title in New York wasn’t filed against Philbrick but against the painting itself, “Untitled by Rudolf Stingel, 2012” and as a court document duly noted, no representation of an attorney was recorded.

It seems that the Stingel needs legal aid and the action must set a precedent for a painting being the sole defendant in a court case.

“The Guzzini filing in New York seeks to clear title for the Stingel,” said a spokesperson for Christie’s, “after the fraudulent activities of the selling agent (Philbrick) involved in the sale were discovered. Christie’s agrees that determination of rightful ownership of the Stingel work by the courts is the next necessary step forward.”