The increasing success of art thieves is not a pretty picture

New York. Alarm bells are ringing worldwide over the accelerating boon in art thefts from churches, historic sites, museums, commercial galleries, and private homes. No one knows the exact figures—it could be as high as $5 billion a year—but experts agree incidents are woefully underreported. Last March, when two thieves in police drag bluffed their way into the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston in the dead of night and made off with some $200 million worth of art—the biggest heist in history press accounts pilloried the institution for poor security and, more incredibly, its lack of theft insurance on their trove of masterworks, many handpicked by the revered art connoisseur Bernard Berenson.

Police composite drawing of one of the two suspects in Gardner Museum heist.

But Steven V. Keller, a museum security consultant in Deltona, Fla. and former security chief of the Art Institute of Chicago says the Gardner theft “could have easily happened in most museums in this country. Most smaller museums don’t have the resources to grapple with security. They have higher priorities.” Ironically, Keller had consulted with the Gardner several years ago on its planned new wing including back-to-back

fortified control rooms that would have prevented this type of theft. Lack of funds scuttled the project. Keller believes the Gardner theft will shake museum directors “back to reality.” But even increased vigilance may not deter a commissioned thief from stealing, even if it means—as it did in the Boston theft—cutting near-priceless paintings out of their frames to make transport easier.

“When you hire someone to steal a painting,” says Robert Volpe, international art consultant and famed former “art cop” of the New York Police Department, “you’re commissioning an ordinary thief who knows and cares nothing about art. He’s given a shopping list and that’s it.”

So far, it’s a cold trail in Boston despite Sotheby’s and Christie’s joint offer of a $1 million reward for the return of the 12 masterpieces. The implied provison of no questions asked has triggered critics to call it ransom. “If it ever became known to the tadboys,’ no art in the world would be safe,” says Harold J. Smith, of Smith International Adjusters, which investigates and tries to recover stolen art for Lloyd’s of London.

“Obviously they had an intent for those paintings,” says Smith. “They’ll put them out of circulation for a few years and then try to launder them back into countries, like Japan and Switzerland, for example, whose laws make it extremely difficult for the original owner to recover.” Japanese law does not require buyers in good faith to return paintings if two years have elapsed since the theft or loss. Still, it would require remarkable chutzpah for any buyer to claim ignorance over a “hot” Vermeer.

The Boston caper was a far cry from the modus-operandi of Florian Fielder, the 23-year-old West German an student Paris police arrested list year. Fielder took some $3.2 million worth of art from a number of Paris museums, including small works by Derer and Corot, to “admire them quietly at home.” Using recommendations from his art professors, the student obtained non-paying jobs at several museums to steal on the job. Police officials said he had no intention of selling the works. Whether professional or amateur, an theft is out of control on every continent.

“What worries me most,” says Constance Lowenthal, head of the New York based International Foundation for Art Research (IFAR), which houses the world’s largest computerized art-theft registry, “is the loss of public access due to security concerns, that our museums will be considered safe only if we turn them into Fort Knox. What good is a museum if it’s only a vault?”

Lowenthal’s concern is not far-fetched. France’s director of national museums, Jacques Sallois, temporarily closed five small Paris museums, including the studio-homes of Gustave Moreau and Eugene Delacroix, to all but pre-arranged group tours following a rash of daytime thefts there on July 4. During museum hours, a small Renoir portrait was taken from the Louvre, a 19th-century landscape by Paul Hurt was stolen from the Musee Carnavalet and a portrait by Ernest Hebert was filched from the Musee Hebert. The Hebert was cut from its frame so the alarm attached to the back of the frame remained silent. According to Lowenthal, ripping off places like the Hebert “is like taking candy from a baby.”

On Sept. 22, Paris police arrested the suspected thief of the July 4 spree, recovering the slashed Renoir—valued at $1 million—the Hebert portrait, as well as a 15th-century portrait of a Venetian doge stolen the day before in yet another daylight burglary, this one from the Museo Correr in Venice. Apparently, the country-hopping art thief – used the same method of hiding the painting under his coat before disappearing in the busy square.

Reached in Paris, a press spokeswoman for Director Sallois said the shuttered museums will reopen “in the ‘near future,” after increased security measures are installed, including video-surveillance cameras and alarm systems. They will also adopt a simple but more secure hardware to anchor the pictures to the wall.

During the interview at IFAR’s headquarters in New York’s Explorers Club, where a stuffed polar bear stands guard one flight down, a Madison Avenue gallery located six blocks away called to report a theft. A young man in a black leather jacket walked into the Weintraub Gallery and pulled a Leger painting, Deta fieurs et element mecanique, off the wall closest to the door and exited to a waiting car in a matter of seconds. “Mayor

Dinkins, Help!,” read the black-bordered ad placed by the gallery that Friday in the New York Times, positioned underneath the weekly auction column. “We ask you to intervene with the Police Department to find the robbers and to return the painting to us. This has happened before, it is happening again!”

Even with computerized data bases, the scope of art theft is all but impossible to track. “It’s an enormous market,” says Dr. William Lawrence, an economist and author of an influential paper on art theft. “The industry simply doesn’t want to recognize it as a serious problem,” says Lawrence, “as if to say, don’t touch the art world, it’s pure.”

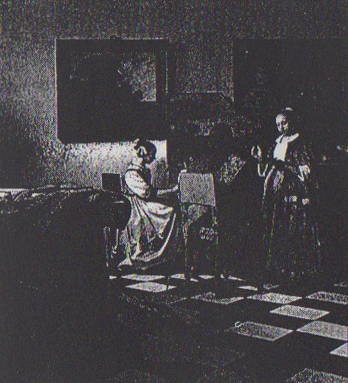

Vermeer’s The Concert, still missing from the Gardner Museum in Boston.

Lawrence estimates that only 20-30% of art theft is reported in the U.S., and in Europe it may be as low as 15%. These statistics are low because collectors often do not like to draw attention to their art holding for reasons of security, privacy, or taxes. Many victims do not know about the reporting agencies, and

even if they did they would find that the odds are against them: it is estimated that less than 20% of reported stolen an is ever recovered. “As an international crime, art theft is now second only to illegal drug trafficking when measured by the dollars involved.”

According to Lawrence, “some stolen art, distributed through large and complex underground networks, eventually becomes ‘legitimate’ by being ‘washed’ through numerous re-sales. It reappears in museums, galleries and exhibitions throughout the world.”

A recent case in point as described by Philip Saunders, publisher of England’s Trace, a magazine for retrieving stolen works of an and antiquities, involved two Postimpressionist paintings stolen from France last year and subsequently used as collateral for a bank loan in Switzerland. The borrowed funds financed a drug deal in Florida. The bank seized the paintings from the scoflaw borrower only to discover—once they tried to sell the art—that their collateral was hot. Saunders said he could not expound on the details because the case was before the courts, and Interpol was still investigating. “It’s not the first time this has happened,” he added.

With increasing sophistication and involvement of knowledgeable art-world figures, the process of converting hot art into cold cash is getting easier. Moving stolen art to a far away market, say Hong Kong or Johannesburg, greatly improves the odds of achieving full market value. Without a central computerized registry of art theft, dealers and secondary market types can always fall back on the cushion of”gee, I didn’t know.”

Says one expert, “As an international crime, art theft is now second only to illegal drug trafficking when measured by the dollars involved.”

“It isn’t a pretty picture,” punned Canadian Interpol art historian Louise Blas in a phone interview from her Ottawa office of the Cultural Property Unit in mid-September, a few days after a multiple art theft from the Basilica in Old Quebec. “My impression is, it’s out of the country already.”

Escaping mention in the U.S. press, the Quebec heist was initially billed as Canada’s largest art theft, with seven pictures, attributed to such masters as Goya, Zurbaran, and Dolci, worth as much as $10 million. Though Blas said only two of the seven were signed, “even if the ‘attributed to’ paintings turned out to be fakes, they were good ones from the 19th century and the group would still be worth several million. Can you imagine all the dusty Baroque art sitting around in churches in Quebec?” queried Blas.

Whether the “shopping list” calls for Cezannes or Leroy Neimans, techniques of art theft rarely require great imagination. Only the likes of Napoleon and Hitler, or perhaps Lord Elgin, distinguish themselves from the subsequent legions of lesser thieves who’ve stolen vast quantities of second- and third rate art. Rarely do these thefts make it into IFAR’s computerized registry, let alone the morning papers.

Recently, the still-evolving tale of the late Joe T. Meador, the U.S. Army lieutenant who stole a magnificent horde of rare illuminated manuscripts belonging to a church in Quedlinburg, Germany shortly before the Nazi surrender in 1945, rekindled the 1134,11,— of spectacular art theft under the smokescreen of war. While his heirs struggled to retain a portion of what Meador called his “Nazi loot,” a much happier story was unfolding in Moscow. Viktor Baldin, a former captain in the Red Army, returned 362 masterworks to a

German museum, including a drawing study for Starry Night, 45 years after he rescued the abandoned trove from a cellar in Berlin.

But the same cold-war thaw that allowed Baldin to repatriate the works has also caused Soviet-based thieves to go after private collections and spirit them abroad for resale. According to Tans press accounts, “Obviously attacks on art collectors arc extremely well thought out and thoroughly organized by those who sell stolen works of art, above all by those who sell them abroad.” The art crimes ranged from the robbery of Viktor Magids’ Moscow apartment, which contained a “valuable collection of Western European painting,” to the murder of an art collector in Odessa during a robbery attempt.

The U.S.S.R.recently joined Interpol, the international criminal police organization, so art thefts committed there will be reported to all member countries. So far, though, no insurance program currently exists in that country to cover private art collections.

One thing is certain: until organizations like IFAR and England’s Trace perfect a centralized art theft registry and market that service world-wide, the epidemic will continue with ever-increasing efficiency. IFAR’s recent interfacing with CENTROX, a world auction monitoring service, will enable the organization to daily track stolen art in their archives with upcoming auction sales in over 160 salesrooms worldwide. It is Lowenthal’s hope that this new technology will eventually stymie thieves so that they’ll “go back to stealing furs and jewelry.”