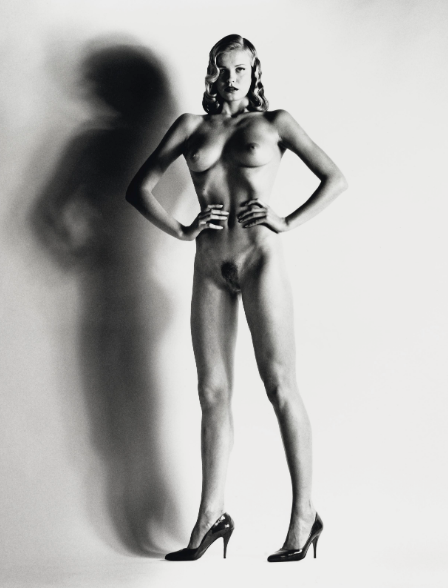

HELMUT NEWTON, Big Nude XIV, Nice, 1993

gelatin silver print

signed, dedicated, titled, dated, inscribed in pencil and copyright, credit, and reproduction limitation stamps (verso) 11 7/8 x 15¾in. (30 x 40cm.)

Helmut Newton’s sizzling images of gorgeous, nude women pushed Buttons and spoke to society’s fixation on beauty and glamour. Today, they fetch huge sums at auctions.

Few artists have bars named after them, let alone a museum dedicated to their legacy. Photographer Helmut Newton has both, as evidenced by the Newton Bar in Berlin where you can sip a cocktail or espresso in leather club chairs with a dramatic backdrop of his celebrated “Big Nudes” covering a wall of the popular watering hole. Across town stands the four-year-old Helmut Newton Foundation, housed in an ornate building that was formerly reserved for army officers during the reign of Kaiser Wilhelm II. It houses thousands of the famed photographer’s works as well as archived troves of Warhol-like memorabilia, including a re-creation of Newton’s Monte Carlo office.

Newton was among only a scant handful of commercial photographers who were able to vault from the magazine page to the gallery and museum wall. The list of those achieving that distinction includes the American fashion and portraiture stars Richard Avedon and Irving Penn. But if you add the caveat of sizzling auction prices garnered for these twentieth-century masters, the list grows even more exclusive.

Roaming around that exclusive pantheon is Newton, the Berlin-born fashion photographer, who after an idyllic and decidedly spoiled childhood as Helmut Neustädter, the son of a rich button manufacturer, barely escaped Nazi Germany as a teenager and spent lean years living in Singapore and Australia before establishing his astonishing career in the early 1960s.

In his 2002 autobiography, Newton described why he was so enamored with the medium: “The beauty of photography is that it’s comparatively cheap to produce, can be done quickly with the minimum of personnel and equipment, and if you screw up one job there is always another one that might work out—also, one does not have to get up early in the morning.”

Ironically, that laconic and even self-deprecating philosophy helped make him a superstar and the subject of gallery and museum exhibitions around the world. “He had a kind of cult status beyond the art world,” says Simon de Pury, the head of the New York/London auction house Phillips de Pury & Company and the co-owner of the Zurich gallery de Pury & Luxembourg, which represents the Newton estate. “Every time we had an opening of one of his exhibitions, they were mob scenes. None of these other photographers had this kind of star status beyond the photography community.”

Even his death was remarkable and legend building, with Newton going out James Dean—style in 2004, crashing his Cadillac Escalade SUV into a break wall adjacent to the trendy Hollywood hotel, Chateau Marmont, after suffering a heart attack at the wheel. He was 83 and until that moment had remained phenomenally productive.

Newton and his actress-turned-photographer wife, June, aka Alice Springs, had wintered and worked at the Chateau Marmont for years, taking a seasonal break from their sumptuous digs in Monte Carlo where Newton had lived since 1981 after a long stint in Paris, exactingly churning out a gigantic oeuvre of unforgettable images for the American, British, French and Italian editions of Vogue magazine as well as other storied fashion publications and Vanity Fair.

“He never left anything to chance,” recalls his widow, June Newton. “He might have used chance, but he never relied on it. Sudden changes of weather challenged him—he adapted, changed plans, he used the elements and never quit a job because of bad weather, and no one ever left the set until he got what he wanted. Work was his mistress.”

Newton’s sizzling and sexy images set against startling interiors or stunning outdoor backdrops in Berlin, Paris and New York not only advertised haute couture, lots of lingerie and less exclusive off-the-rack fashions, but established an unmistakable and much copied look that brilliantly captured the popular culture. “If you open any Vogue magazine,” says Zurich dealer Andrea Caratsch, who represents the Newton estate with fellow dealer de Pury & Luxembourg, “or follow the press campaigns of Dolce & Gabbana, they all sell sex. He was the pioneer of that.”

Newton was especially keen on photographing his subjects at night on the cobblestoned streets he knew so well, preferring a plain 500-watt photo floodlight and unadorned camera over more high-tech strobe lights and motor drives. He turned the scenes into movie-like vignettes, injecting his quirky brand of humor and sense of danger into the settings, going so far as using elaborately rigged mannequins precariously perched on a bridge over the Seine, as if voyeuristically capturing the moment of a suicide.

“So many of his pictures work on so many levels,” says Philippe Garner, the London-based international head of Christie’s photograph department, who’s also written extensively on Newton. “They’re about a kind of social reportage, and the beautiful girl or the erotic scene, that’s just the first touch. It’s the backstories that keep the pictures interesting. If it was just a succession of beautiful women, it would get kind of boring and wouldn’t have their staying power.”

Everything about Newton seems larger than life, including Sumo, the 66-pound Newton tome published by Taschen in 1999 as a signed limited edition of 10,000. Edited by June Newton, the 464-page behemoth came with a special stand created by superstar designer Philippe Starck. The book was originally offered at $1,500; remaining copies now sell for $10,000 at Taschen stores and mint examples have fetched even higher prices on eBay.

Not surprisingly, escalating market demand for Newton’s work has made certain of his iconic images soar in value, especially since his death. “From the moment Helmut died,” recalls dealer Caratsch, “we were drowned with requests for prints of his. We raised the prices more massively and decided to be very restrictive in terms of what we sold and to whom we sold to.” The strategy has paid off handsomely.

While many of his smaller scaled and less important works can still be found in the $10,000 range and under at auction and galleries, such as the 14 7/8-by-11 5/8-inch Cyberwoman #6, 2000 that sold at New York’s Swann Galleries in February 2007 for $10,200, major works consistently hit the six figures. Big Nude III, Paris, 1980, featuring a statuesque brunette in high heels, set against an otherwise stark shadow-producing backdrop, shot to a record $378,816 when it sold at Christie’s London last May. One of 13 black-and-white prints from the edition, the photo measures 91 by 41 7/8 inches, matching the scale and wall power of a major contemporary painting.

Between 1980 and 1993, Newton produced approximately 21 versions of the big nudes, which were inspired by police identity photographs of German terrorists that Newton had seen years before he transformed those rough mug shots into his own brand of art. A more menacing image, Panoramic Nude with Gun, Villa d’Este, Como, 1989, depicting a long-limbed beauty aiming a handgun at the viewer, with palm trees in the background, sold for about $213,000 at Christie’s London last May. It came from a smaller and thus more exclusive edition of three and was signed by Newton. Christie’s expected the photograph to sell for $100,000 to $140,000, according to the figures published in its catalog. The startling result in the auction salesroom reflects Newton’s posthumous standing as a red-hot commodity.

Another storied and multilayered image in Newton’s prolific canon, Self-Portrait with Wife and Models, Paris, 1981, showing a bored June Newton seated in a director’s chair as one of the nude models stands before a mirror that reflects her body and also reveals the trench-coated photographer in action, fetched $168,000 at Christie’s New York last April. It hailed from a much larger edition of 75, indicating again the growing strength of Newton’s market and the highbrow demand for work of even large editions.

The Newton market juggernaut was also in evidence in December at the trendy Art Basel Miami Beach art fair, where Domestic Nude O in an Airstream Trailer, Hollywood, 1985—part of an edition of 10—sold for $40,000 at the booth of the Kicken Berlin gallery of Berlin, Germany. The image melded Newton’s signature combination of an unusual landscape (the vintage design camper parked in a busy urban setting with the Playboy Tower visible in the distance) and a beautiful woman, sans clothing, standing in the open doorway of her mobile trailer. Since the Miami fair, the gallery sold another version of Newton’s most acclaimed series with Big Nude XV, Raquel, Nice, 1993 for $200,000.

In New York, a large-scale Newton triptych, Walking Women, Paris, 1981 was sold late last year to a private collector for about $500,000 by Madison Avenue dealer Scott Cook. “I end up selling things [by Newton] more in Asia and Europe because Americans, for some reason, are so prudish,” says Cook. “The husband wants them, the wife doesn’t. It’s kind of a bachelor’s market, you know?”

Though Newton has photographed (fully clothed) heads of state, including former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher (the 1991 work hangs in London’s National Portrait Gallery), he’s been critically blasted in the past for his allegedly macho, decidedly not politically correct, lurid and demeaning depictions of women. He, of course, saw himself as championing their power and beauty in the world. “He was a visionary,” says Daile Kaplan, an art historian and director of photographs at the New York—based auction house Swann Galleries, “because when he was pushing all those buttons, he was offending a lot of people by depicting women as sex objects, unabashedly and transparently. But at a certain point, there’s a power that they radiate and they came to be emblematic of what was going on in our culture, which is to say, this whole preoccupation with fashion and glamour.”

Collectors have also gotten the picture that Newton had a distinct vision. “I was fascinated by Helmut’s way of dealing with women, how women were the central part of the picture in a very powerful way,” says New York philanthropist and former film producer Leon Constantiner, considered the world’s largest collector of Newton photographs with approximately 500 prints.

Constantiner, who at one point had more than 50 Newton photographs hanging in his Manhattan apartment, began collecting his work in 1990, at prices he now says are equivalent “in this market to a large Starbucks latte.” The first acquisition was at Sotheby’s New York, where he paid about $8,800 for an enlarged contact sheet print of Self-Portrait with Wife and Models that included 12 variants of the now esteemed image culled from that photo shoot. That work today could fetch $200,000, according to Christie’s Garner.

The beauty of Newton’s market and his ever-expanding legacy is that even if you can’t afford one of the “Big Nudes,” there’s a rich and downright prolific assortment of other images that radiate the photographer’s sexy and crisply stylized aesthetic.

Judd Tully is the editor-at-large of Art & Auction magazine and writes frequently about the international art market and contemporary art trends for a number of publications.