Sam Gilliam, Crystal, 1973, 96″x34″, acrylic on canvas

In a steady and powerful climb, African-American artists have gained significant traction on the international art map after generations of what may be termed benign neglect or worse. They are appearing with increasing frequency in a wide range of venues—solo exhibitions in museums 88 and galleries, international biennials, art fairs—as well as shining in the high-stakes auction room limelight. A case in point is Mark Bradford,

the Los Angeles–based artist who will represent the United States at the 57th Venice Biennale next year. There is no predilection as to style; works range from abstract painting by the likes of Sam Gilliam, Stanley Whitney, and Jack Whitten, to Conceptual examples from practitioners such as Adrian Piper and McArthur Binion, as well as figurative and multimedia pieces by artists like Betye Saar and Kara Walker.

Enabling this rise—apart from the raw talent that has made it possible—is a handful of stalwart contemporary art dealers who championed some of these figures long before they achieved critical and market recognition. And it should be noted that many of these dealers happen to be white, as are the overwhelming majority of curators and museum directors who continue to dominate the art world.

As Whitten, who at age 76 recently joined the international roster of Hauser & Wirth, pointed out in a Bomb magazine interview with poet Kenneth Goldsmith back in 2004, Only if you have commercial representation and you have someone who is a believer in you and the work, and is willing to promote it, is work sold. Work sold through gallery situations,” continued Whitten, “comes through an endorsement of the gallery museum world with a bag of collectors to back it up. If you don’t have that kind of interest, you can stand on your head out there for 20 years, and it won’t sell.”

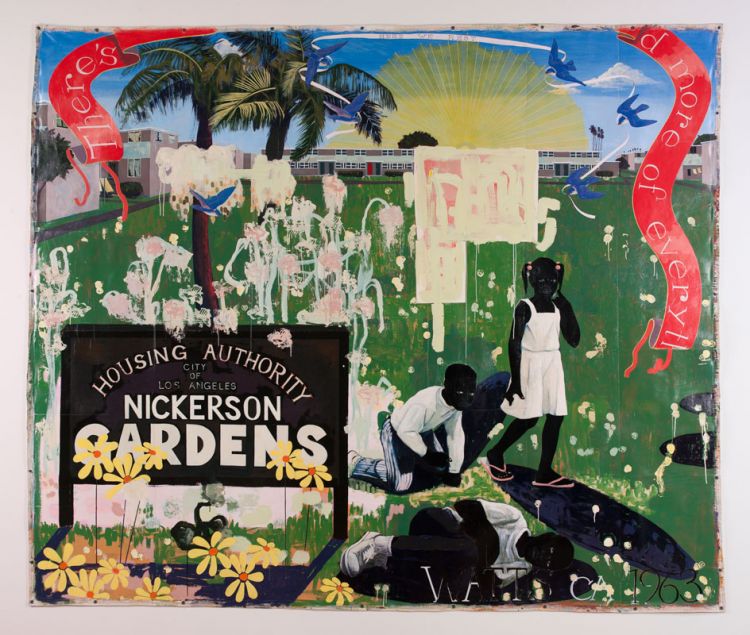

Kerry James Marshall, Watts 1963, acrylic and collage on canvas, 1995

A number of gallerists have campaigned to broaden this for-profit legacy, among them Kavi Gupta in Chicago and Michael Rosenfeld and Jack Shainman in New York. Since 1993, Shainman has been devoted to the figurative paintings and mixed-media creations of Kerry James Marshall, whose traveling survey, “Mastry,” opened to rave reviews at New York’s Met Breuer in October a fur a critically acclaimned debut in Chicago at the Museum of Contemporary Art. It was MCA’S fifth highest attended exhibition, whose visitors included First Lady Michelle Obama.

“When I went to visit Marshall in Chicago in 1992., when he had a show up (“Terra Incognita”) at the Chicago Cultural Center,” recalls Shainman, “I was instantly bowled over by his work. I mean how I walk into a room and my socks start to roll up and down on their own, it is a sure sign for me. I immediately said, ‘let’s do a show’.”

Betye Saar, Dark Journey: The Game of Destiny, mixed media assemblage, 2016

Since then, Shainman has mounted six solo shows for Marshall in New York, the first in 1993. From the very beginning of that relationship, Marshall had a single vision priority, according to the dealer, “to have his paintings in the museums where there were no black figures represented.” In that first exhibition, Shainman sold two paintings to museums, including Wandering in Voyager, 1991, a 71/2-by-7-foot acrylic and collage on canvas, which he placed with the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. (The work’s title refers to the schooner Wanderer, one of the lastships to secretly transport African slaves to the United States, in 1858.) “But the show wasn’t an overwhelming success,” says Shainman, “and when I told Marshall about the sales afterward, hesaid, ‘Yeah, I guess peoplearen’t really ready to hang with the black folks in their living rooms yet.'” At the time, says the dealer, a major Marshall painting sold for $7,500.

That has certainly changed. Plunge, another of his mixed-media paintings from 1991—the title relating in part to the artist’s immersion in the art world—sold at Christie’s New York this past May fora record $1,165,000. Philippe Segalot and David Zwirner, who represents Marshall in in London, were part of the elite posse of underbiders.

Asked if he felt a shift was occurring for artists of color, Shainman says, “I think it’s just coincidental that all of these artists are getting this attention. The art world is now much more open to the ‘other’ rather than just focusing on white artists, but we still have a long way to go.”

Shainman hasa deep roster of other nonwhite artists, including Nick Cave, Hank Willis Thomas, Barkley L. Hendricks, Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, and Carrie Mae Weems. Weems opened a two-venue exhibition at the Shainman galleries in Chelsea in October.

In some ways the recent focus on African-American artists could just as easily be about Chinese contemporary art or art from Latin America, observes Franklin Sirmans, the recently appointed director of the Perez Art Museum Miami and former chief curator of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, where his last project, a survey exhibition of Toba Khedoori, a multimedia artist of Iraqi heritage, opened in September.

“The market,” says Sirmans, “is constantly Cooking for the new, and I think we curators also have an appetite for things we don’t know. We have to look for the new somewhere. I think some people are more courageous to do that, and the marketplace comes along a little bit later.”

Betye Saar, the 9o-year-old Los Angeles artist who is a leading figure in the arena of assemblage art, recently vaulted onto the international art stage with “Uneasy Dancer,” a comprehensive exhibition of more than 8o objects at the Fondazione Prada in Milan, which runs through January 8. “Uneasy dancer” is the phrase Saar has used to define both herself and her practice. The show is the artist’s first in Italy.

“Prada is giving a lot of opportunities to people who are under represented for what they have given to the art world,” said Bennett Roberts of Culver City, California gallery Roberts & Tilton, Saar’s primary-market dealer. (His partner, New York dealer Jack Tilton, championed the work of David Hammons before that artist’s market went global.) Stateside, “Betye Saar: Black White,” a show of mixed media works executed between 1966 and the present, explores race relations reflected in linguistic usage. It opened in September in one of the two exhibition spaces at Roberts & Tilton; the other space is occupied by “Betye Saar: Blend, ” which opened in October. Both chapters of the two-part exhibition are on view through December 17.

As Roberts explains it, “Betye is kind of like Joseph Cornell; she’s a quiet, philosophical, political poetess who tries to show what it was like to be her in a world that didn’t really want to allow her in. She isn’t talking in nice tones but in realistic, political ones.” Saar’s prices, which ranged from $500 to $5,000 during the time she was represented by the now-shuttered Jan Baum Gallery in Los Angeles, he says, have increased to $35,000 to $100,000. “She’ll be in a group show at Tate Modern next year, where she’ll have her own room, but a lot of curators still don’t know who Betye Saar is, even though she’s already in the history books,” says Roberts. “It’s catch-up time.”

Roberts acknowledges a significant price gap between Saar’s work and that of Kehinde Wiley, another gallery artist whose paintings typically range from $t5o,000to $200,000. “Saar’s work is much more difficult, and a market for it was never really built,” he says. Asked why he thinks she and other undervalued African-American artists have gained more critical attention and market torque, he observes, “I think the art world is back to a point where they’re reevaluating what has been left to the side,” One has only to think of the recent explosion of prices for lesser-known members of the avant-garde Zero Group and other European postwar movements, such as Arte Povera, to appreciate that sideline view.

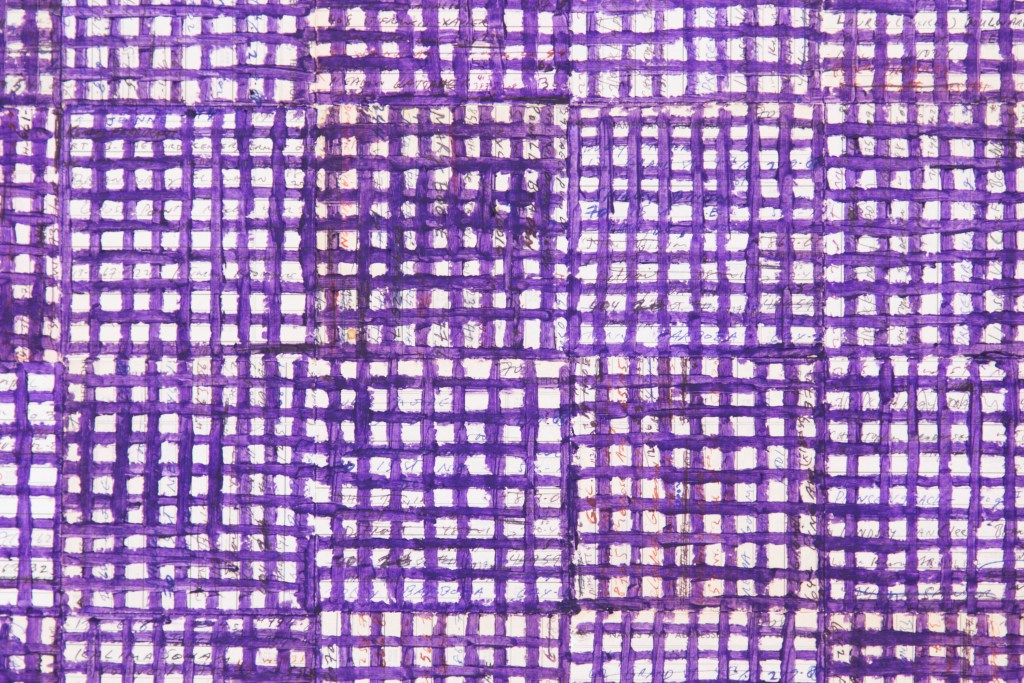

Stanley Whitney

SunRa, 2016, Oil on linen

96 x 96 inches

Back in New York, another long-brewing career has burst into full view with the color-charged, irregular grid-patterned, geometry anchored paintings of Stanley Whitney, whose first solo museum survey, “Dance the Orange,” at the Studio Museum in Harlem in 2015, electrified his market after decades of sales that were modest at best.

Team Gallery founder Jose Freire became aware of Whitney’s work in 1987 when he was a young gallerist at Fiction/Non-Fiction in the dying days of the East Village art scene. “When I first saw his work, it was this jolt of color, like a thing rd never seen before.” Initially Freire staged two Whitney solos, in 1989 and 1990, but not much sold. The gallery eventually closed and Freire and Whitney went their separate ways.

Once Team got smoking in 2004—with three of the gallery’s artists represented in the Whitney Biennial—Freire approached Whitney again and challenged him to join a gallery where “no one comes to buy abstract paintings and no one comes to buy the work of old people.” Whitney was in his early 60’s at the time.

It took several years for Whitney to gain his sea legs at Team, where Freire paired him in small group shows with younger artists. At ArtBasel Miami Beach in 2009, he showed the artist’s work with that of Ryan McGinley. Three solo exhibitions followed, including one at Team’s L.A. Bungalow space and a display of a trio of eight-foot-square paintings at the gallery’s satellite Wooster Street space, which Freire characterized as “the most magnificent show I’ve had in my gallery.” Still, he says, nothing sold. Then, in the wake of Whitney’s critically celebrated Studio Museum outing, Freire “sold every painting we had in our inventory and everything in the artist’s studio.”

Whitney,who has also exhibited at Galerie Nordenhake in Berlin, recently joined London’s Lisson Gallery and has made waves at art fairs under that international flag. On January 21, 1017, “Focus: Stanley Whitney” opens at the Modern Art Museum in Fort Worth.

McArthur Binion, “DNA: Seasons: XI,” 2016. Oil paint stick and paper on board, 72 x 96 x 2 inches

Another artist on the rise, albeit in a somewhat quieter way than Whitney, is Minimalist McArthur Binion, a Mississippi-born artist formerly known as an inspiring and influential teacher at Columbia College Chicago, where he went after a stint in New York early in his career. Binion, who holds an MFA from the Cranbrook Academy of Art in Michigan, earned a fantastic New York credential early on when he was selected to participate in the Artists Space inaugural group show in November 1973, which wascurated by Ronald Biaden,Sol LeWitt, and Carl Andre. Bladen, a Minimalist scuiptor picked out Binion’s stringently Minimal paintings in oil stick and crayon on aluminum,while Andre chose Mary Obering and LeWitt picked Jonathan Borofsky.

Today, Kavi Gupta and his eponymous gallery—with the help of Galerie Lelong in NewYork, since 2015 —are bringing Binion’s important body of work to light, which has not been an easy task. “He was on the scene tin Chicago), but no one really knew what his work was. He kept it hidden in his studio,” recalls Gupta, musing on how difficult it was even rearrange a studio visit, which he finally did in 2012.

“He had all these crates sitting in his studio, covered in dust, but each chronologically labeled 1970, 1971, 1972,” says Gupta, “and about half of them had this Artists Space sticker on them. All of a sudden, he’s pulling out these amazing four-by-six-foot works on aluminum that he had done in ’72., predating the white Minimalists of that period like Robert Ryman. It was like Sol LeWitt meets Agnes Martin, and it was insane.”

Gupta, who was also an early champion of fellow Chicagoan Theaster Gates, showed four of those works from Bin ion’s studio at Art Basel Miami Beach in 2012, which, he says “started a frenzy.” He adds that Chicago collectors Peter and Jill Kraus were the first to buy a Bin ion from him. “The Art Basel exposure really helped. Once you get enough of those collectors behind the work and they are talking to their curators and other collectors, then all of a sudden the system starts working.” Gupta says that recent paintings by the artist range up to $85,000 and the remaining works from the 1970’s go up to $175,000.

“The art world,” says Gupta, “has shifted and isa little bit less New York—centric and white-centric, and we were able to really find the hidden things that were happening. It’s a good moment for that.”

Among the artists who have been influenced by Binion is Rashid Johnson, who was one of his students at Columbia College. The Chicago raised, 39-year-old artist initially drew fevered interest from his 2001 New York debut in Thelma Golden’s “Freestyle” exhibition at the Studio Museum in Harlem, and his multimedia and monumentally scaled exhibition, “Fly Away,” at Hauser& Wirth in Chelsea garnered widespread attention this past fall.

“McArthur brought Franklin Sirmans to lecture, he brought in Stanley Whitney to talk, and I was there,” says Johnson. “He molded me by his decisions and who he decided to introduce me to. He’d say, ‘Look at this, think about this, talk to this person, and understand your history and appreciate your place in it and be somewhat fearless about that.'”

In that spirit, Johnson, who is represented on the West Coast by gallerist David Kordansky in Los Angeles, went on to curate an important exhibition of works by Washington Color School artist Sam Gilliam at Kordansky in 2013. “Hard-Edge Paintings 1963-1966” was Gilliam’s first exhibition with the gallery, and it helped reinvigorate and internationalize his already storied standing in the art world.

“The reaction was incredible,” recalls Johnson, speaking of the work that was done when Gilliam was in his early 302 and left largely unseen for 50 years. “The thing that surprised me the most was how many younger artists seemed to be unfamiliar with his project and how many more established curators who were familiar with the work felt enthusiastic about getting the opportunity to participate and look at it again.” Gilliam’s Opening,1965, a diagonally striped 36-inch-square painting from that group, sold for $161,000 against a SZZ,000 high estimate at Christie’s New York in November 2015.

Freshly ensconced in her t 2,000-square-foot Harlem gallery (the original home of the Studio Museum), former Chelsea dealer Elizabeth Dee talked about her relationship with the Berlin-based Conceptual artist Adrian Piper, whom she first studied as an art major—with a minor in critical social thought—at Mount Holyoke college.

I studied her work and wrote about it extensively from my early student days,” recalls Dee, who included Piper in a 2006 group show based on the Iraq War; a solo presentation of historical works at the Armory Show in 2008; another art fair solo booth in 2009, “Partially Buried” at Art Basel; and “Past Time: 1973 -1995” at the rented-out Dia Center building in Chelsea in 2010. Dee also staged two Piper solos at her Chelsea space, “Everything” in 2008 and “The ProbableTrust Registry” in 2014. The former was the first New York solo show of Piper’s since her 1999-1000 retrospective at the New Museum.

“What I discovered with Piper’s work in terms of her resonance within a museum context,” says Dee, “is that institutionally, there was not really any cohesion in what was considered to be the most important work. The opportunity to try and bridge these differences and try to work with museums was interesting to me. If they had 197os works, to have them look at the ’80s and ‘9os, when she was dealing with issues of blackness and race. Or if they had that work, try to locate some Conceptual works they might consider from the ‘7os.” Important acquisitions were made by Washington D.C.’s H rsh horn Museum, the Sackler Center for Feminist Art at the Brooklyn Museum, and the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis.

As far as Piper’s collector base, Dee notes, “many of my collectors internationally had David Hammons, for instance, but didn’t have Piper and weren’t really aware of her work unless they had studied art history or were involved in the history of Conceptual art.” According to Dee, prices for Piper’s works range from $50,000 to $250,000. Kara Walker, the MacArthur Foundation grant-awarded painter, is among the few African-American artists who didn’t struggle through decades of inattention before stardom struck. Rather, she drew almost instantaneous critical attention.

Brent Sikkema of Chelsea’s Sikkema Jenkins first showed Walker in 1995, at his fledgling, living room-scaled Wooster Gardens/Brent Sikkema gallery in SoHo, with a show titled “The High and Soft Laughter of the Nigger Wenches at Night.” He exhibited her work again the following year with “From the Bowels to the Bosom.” “Karaisa unique artist,” he says, “in the sense that when she first appea red, so young, just out of graduate school at the Drawing Center in 1994, she established herself with that first big wall installation [now in the Museum of Modern Art in New York]. It was just picked up by curators, and she really bypassed the conventional narrative, which would have an artist going to a significant gallery, which I was not at the time. She didn’t get Mary Boone or Metro Pictures or Jeffrey Deitch. She just got picked up instantly by really important curators and started having all these museum shows.”

One of the large wall installations from that first Wooster Gardens show sold to Laurance Rockefeller for $14,000, according to Sikkema, and two others went to Deitch and Peter Norton. Sikkema says Walker’s wall installations these days go for $750,000 to $850,000, and big drawings of the type recently shown at the Cleveland Museum of Art range from $125,000 to $275,000.

“Her work,” he says, “is just as much about gender as it is about race. It pushes all of those buttons.”

“The fact that some of these artists are starting to get that kind of attention,” says Rashid Johnson, “is very much deserved, and the fruits of those labors should absolutely come their way if they’re going to come anybody’s way. They should share in the spoils.”