How the government’s Art in Architecture program really works

On April 14 at 11 a.m. with due pomp and ceremony, Claes Oldenburg’s batcolumn will be officially un-veiled (from red satin drapes) and dedicated in its permanent site in front of the Social Secuirty Great Lakes Payment Center at 600 W. Madison. Shaped like a baseball bat, constructed of lattice-work steel, the batcolumn will be 100 feet 8 inches tall and 9 feet 9 inches in diameter at its largest point.

Appropriately coinciding with the opening of the Chicago baseball season, the dedication will be a gala affair complete with testimonial dinner at the foot of the sculpture in the evening. On hand for the ceremonies among all the art and government dignitaries will be Chicago’s famed Ernie Banks (“Mr. Cub”) to lend his support. How did it all happen? The following article describes in detail the program that brought the batcolumn to Chicago.

From Honolulu to Nashville, the U.S. General Services Administration’s (GSA) Art-in-Architecture Pro-gram (A.I.A.) has flowered into a rapid transit vehicle for contemporary American artists creating commissioned works of art for new federal buildings.

Sprouting from a 1962 “New Frontier” treatise on Federal office space titled. “Guiding Principles for Federal Architecture.” Kennedy’s camelots recommended the incorporation of fine arts in the designs of new federal buildings. GSA, the principal builder, purchaser and landlord for the government took the committee’s advice and in a brief span of four years (1962-66) commissioned 44 works of art, (to the fiscal tune of $1,176,500) ranging from murals and sculptures to mosaics and stained glass panels.

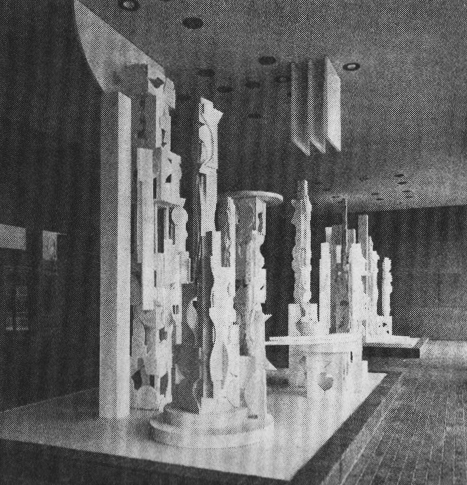

Louise Nevelson, “Bicentennial Dawn,” white painted wood, 1976, 1 42 ft. high. Philadelphia

The program went into a state of suspended anima-tion from 1966-1972 when the combined forces of the War in Vietnam and the skyrocketing inflation in the building construction industry tabled any hope for federal tax dollars earmarked for GSA’s Fine Arts Program. The big sleep didn’t last long.

A new director of the Art-In-Architecture Program, Donald W. Thalacker, initiated new procedures for the selection of artists and brought in the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) to assemble a panel of art experts to nominate 3-5 artists for each proposed commission. The NEA panel would meet at the project site of the new building and after a recommendation of the project architect (detailed in his fine arts proposal) as to the type and location of art wanted, (free-standing exterior sculpture on a plaza or interior mural in a lobby), would hammer out commission choices.

chitecture Design Review Panel (A1ADRP) for finer filtering and finally wind up in the lap of GSA’s head honcho, the Administrator, who makes the selections. NEA’s panel changes for each new project, encouraging local or at least regional participation in the nominations. This subtle grass roots identification often acts as a flak jacket for GSA when a particular work of art is lambasted by local press or politicians.

The spending formula for GSA art commissions is currently fixed at 3/8 of 1% of the estimated construction cost of the particular federal building. Inflation is not a factor for the commission. During the first phase of GSA’s program, the fraction was 3/8th of 1%. The numbers game is controlled by the administrator, a political appointment. AIA runs on the tacit approval of Congress with no specific legislative authority.

Claes Oldenburg, “Spinning Bat” (state ed. 60) lithograph. pub. by Landfall Press

Sculptor Charles Ginnever, first heard the news of his award on his return from a trip to Europe. The commission called for a free-standing exterior sculpture on the plaza of the new Courthouse and Federal Office Building in St. Paul, Minnesota. “I went out to St. Paul,” said Ginnever, “at my own expense and met with with the project architect and Thalacker. That’s the worst aspect of the system. Everything is on you. The contract itself was relatively smooth sailing. The payment schedules were o.k.”

The contract Ginnever refers to (GSA, Public Building Services Contract for Fine Arts Services) is a standard 18 page shopping list of strict terms and conditions. High on the list— “the Artist shall determine the artistic expression, subject to its being acceptable to the Government. The Artist shall submit to the Government a sketch or other document which conveys a meaningful presentation of the work which he proposes to furnish. in fulfillment of this contract; The Artist shall, without additional fee, make any revision necessary to comply with such recommendations as the Contracting Officer may make for practical (non-aesthetic) reasons. The Artist shall furnish facilities for inspection of the work its progress by authorized representatives of the Contracting Officer.”

Second generation “billboard” artist of the New York School, Al Held, received his contract award in early 1975 to paint companion murals for the new Social Security Administration building in Philadelphia. “GSA was remarkably free of aesthetic kant or restriction,” commented Held in a phone interview from his New York City studio, “1 paint directly on canvas. I don’t work in a pre-conceived way. The drawings I submitted to GSA were just a general style. The were extremely generous. I had tremendous freedom in my stylistic thrust.”

Rewriting to the nuts and bolts of the .GSA Fine Ai vi Services contract,-“All designs, sketches, models, and the work produced under this Agreement for which payment is made under the provisions of this contract shall be the property of the United States of America. All such items may be conveyed by the Contracting Officer to the National Collection of Fine Arts-Smithsonian Institution for exhibiting purposes and permanent safekeeping.”

Seventy year old Ilya Bolotowsky, master of the tondo and living dean of Neoplasticism is a veteran muralist for the federal government, working in num-erous Works Progress Administration (WPA) projects during the 1930’s and early 40’s. With his $45,000 con-tract award for porcelain enamel on steel murals (commissioned in April, 1976) for the Great Lakes Social Security Administration Building on Madison Street in downtown. Chicago, Bolotowsky has the unique distinction of bridging the two major movements of American public art financed by the federal government. During the New Deal, the Russian geometricabstractionist was paid $23.86 a week for his efforts. Commenting on his most recent commission—”other artists were better bargainers than me. GSA got my four murals at a very low price. The payments do not com-pare to the commercial market.” Referring to the con-tract restrictions on ownership the artist valued the sketches submitted to GSA for the murals at $10,000. Since Thalacker took over the reins of the AIA program, GSA has commissioned 52 projects at a cost of $1,660,800 with 22 additional commissions in the planning stage, at $1,204,738.

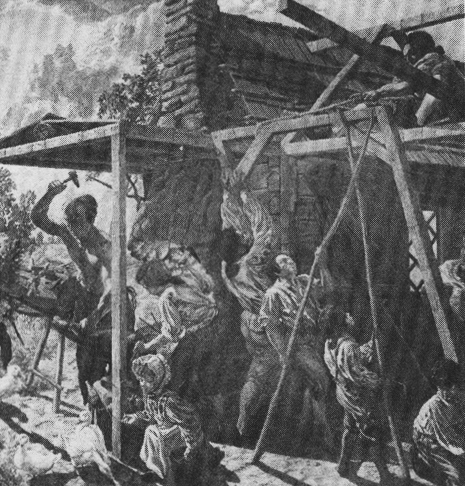

Jack Beal, “Settlement”, one of four murals comprising “History of Labor in America.” Washington, D.C.

The most vociferous critic of the AIA program is Wisconsin Senator William Proxmire. In a press release dated August 30, 1976, the Senator, known for his barbs aimed at Pentagon cost overruns (also his penchant for jogging and hair transplants), awarded his Fleece of the Month award to GSA’s AIA program. “The Fleece of the Month is awarded for the best ex-ample of wasteful, foolish or ironic government spending and culminates at the end of the year with a Fleece of the Year award. I am not awarding the Fleece to GSA because. I am opposed to encouraging art.”

Proxmire’s dander was raised by the $100,000 commission to Claes Oldenburg is his Chicago model for a 100 foot steel baseball bat, titled, Barcolumn. The Senator also questioned Ginnever’s Corten steel Protagoras in St. Paul which reminded him of “a rusty piece of farm machinery left out in the field.” George Segal’s bronze, the Restaurant (a $60,000 commission) was also included its the Wisconsin Senator’s publicity engendering diatribe.

At the other side of the political art world fence stands New York Senator, Jacob K. Javits. At the dedication of George Segal’s Restaurant at the plaza of the Federal Building in Buffalo, New York on June 28, 1976 the Senator said: “Government needs to be made more real, more meaningful and helpful to our citizens in their everyday lives. This beautiful sculpture, standing before a public building, is a metaphor in bronze to reinforce that government should enrich our everyday lives. Secondly, this work has been commissioned by the GSA, with the advice and counsel of the NEA, as part of their expanding recognition of the inherent place which works of art hold in the architecture of public buildings.”

Proxmire’s dander was raised by the $100,000 commission in lump sums. Individual artists are given time-tables for completion and monies are ladled out in careful portions until the actual date of installation. The Government can always pull out-to wit: “The Contracting Officer may, by written notice to the Artist, terminate this contract in whole or in part at any time, either for the Government’s convenience or because of the failure of the Artist to fulfill his contractual obligations. Upon receipt of such notice, the Artist shall immediately discontinue all services affected.”

To date, no artist has been bumped from a project but as Charles Ginnever aptly observes, “it’s not a clause generated to give you a sense of security.”

Joyce Schwartz, for three years, Director of Commissions for Pace Gallery, Inc, on 57th Street in New York City has the best track record for representing artists chosen for AIA commissions. Lucas Samaras, (Corten steel sunburst sculpture in New Orleans) David von Schlegell (fountain sculpture in Philadelphia), Jack Youngerman (Rumi Dance murals in Eugene, Ore.), and Louise Nevelson (Bicentennial Dawn sculpture in Philadelphia) received commissions totaling $416,000. Pace picks up a nominal 10% commission fee for “details of movement,” shuttling the artist round and about.

Claes “Colossal” Oldenburg’s Batcolumn will be installed on April 12, on the near west side of Chicago in the plaza of the new Social Security Building (Bolotowsky’s murals were installed in October, 1976), nudging the antiquated Chicago and Northwestern Railroad Station. The 35,000 pound steel sculpture soars 100 feet with a 4 foot wide base and 9 foot wide top. Oldenburg is no stranger to controversy or the cityscape of Chicago. A veteran of the Windy City’s infamous City News Bureau he once proposed giant rear-view mirrors for Navy Pier to reflect the skyline. In a limited edition press and photo log compiled by the artist to cover his media movements from May, 1974 to August, 1976, Oldenburg opined:”Newspaper documents are particularly descriptive of public art situations—the work appears in them as it does in the city itself—in mixed, confusing, non-art surroundings.”

At Jack Beal’s dedication ceremony at the $95 million Labor Department Building in Washington, D.C. on March 4, the realist painter’s four giant oil on canvas murals tracing the history of labor in America were unveiled to the syncopated drone of the U.S. Navy ceremonial band. Embossed on the back cover of the slick installation brochure were the words (among others) of President Jimmy Carter—”The arts are a cherished part of the American experience and an important medium of communication. In public buildings such as this they can be effectively used to depict the vitality of our cultural heritage as well as the continuing ability, resourcefulness add imagination of our people coping with problems of everyday life.”

New guidelines are in the works for AIA. The watch-word (no acronym has been invented yet) is “community support through community involvement.” For the first time, mayors of project sites will be informed of pending commissions and encouraged to appoint their own representative for the NEA nominating process but in a non-voting capacity. Regionalism seems to have enhanced its `TP’ (what one Gotham art critic christened trend potential) image and could overthrow its benign neglect syndrome. The 22 projects previously mentioned can credit their limbo state for this new pre-natal revision.

Returning to the studio-loft of sculptor Charles Ginnever in Soho, a last sage remark is due— “In a country that spends 1/2 of every dollar on feat and next to nothing as aspiration, we’re lucky to have anything at all.”

Judd Yully is a New York City based freelance writer, the author of Red Grooms, Ruckus Manhattan, to be published by George Braziller, New York in May, 1977.