Gerhard Richter’s “A B, Still (612-4)” from 1986

(Sotheby’s )

Concerns about a weakening market for contemporary art vanished on Thursday evening at Sotheby’s in New York, as a stellar $276,560,750 auction capped a week chock full of multi-million dollar sales.

Only four of the 64 lots offered failed to sell, for a svelte 6 percent buy-in rate by lot.

The tally approached the high side of pre-sale expectations of $208.5-302.3 million and fell just short of the $294.85 million total of last November’s equivalent auction, in which 44 sold lots sold, including Cy Twombly’s 1968 “Untitled (New York City)” from 1968, which went for $70.5 million.

The total hammer price before fees this round totaled $237,405,000.

All prices reported include the hammer price (final bid) plus the buyer’s premium for each lot sold, calculated at 25 percent of the hammer price up to and including $250,000, 20 percent of any amount in excess of that and up to and including $3 million, and 12.5 percent for any portion in excess of $3 million. Estimates do not reflect the buyer’s premium.

Forty-nine of the 60 lots that sold made over one million dollars and of those, six made over $10 million. Two artist records were set.

The evening began in grand fashion with 25 lots from the esteemed collection of Steven and Ann Ames, a section of the sale somewhat pretentiously titled “The Triumph of Painting.”

Steven Ames, related to the powerhouse American art collecting families of Walter Annenberg, Joe Hazen and Enid Annenberg Haupt, was a longtime trustee of the Whitney Museum of American Art and a passionate art history student.

The Ames group started with Mark Grotjahn’s 60-by-48 inch “Untitled (French Grey Fan 10-90% Butterfly with Warm Grey 90% Between)” from 2006, executed in colored pencil on paper, which brought $1,872,500 (est. $600,000-800,000). New York dealer Andrew Fabricant of Richard Gray Gallery was the underbidder.

It was backed by a so-called irrevocable bid, meaning a third party pledged a sufficient bid prior to the auction to win the picture if other competition didn’t materialize.

The irrevocable or third party-bid has become a powerful inducement and financial instrument in the art auction market, invented to soothe nervous sellers and ensure them a set amount no matter what transpires in the auction room. Backers are generally compensated for this risk taking and the general terms are outlined in small print at the back of the auction catalogue.

The Ames trove as well as the various-owners portion of the sale had a mix of irrevocable and house guarantees, 36 in all (10 house guarantees and 26 irrevocable bids), assuring a decent result, and that formula powered the auction.

Jim Hodges’ spider web-like suspended sculpture “Untitled (Study for Gate)” from 1991, comprised of steel chains, made $1,332,500 (est. $600,000-800,000).

A small-scaled but potent Philip Guston late figurative painting, “Untitled (Smoking)” from 1979, featuring a caricature like figure, most likely the artist, holding a smoldering cigarette against a luridly and all-over pink background sold for a whopping $3,612,500 (est. $1.5-2 million).

Though he lost out to a telephone bid, the underbidder, seated on the aisle, took sips of white wine during the bidding duel. (Bidders these days normally hold nothing but cell phones.)

Guston’s Abstract Expressionist-era peer Willem de Kooning was represented by “Untitled XXXIX” from 1983, a 70-by-80-inch abstraction instantly recognizable as late work due to the lighter palette and more open areas of the composition. It sold to Andrew Fabricant for $9.8 million (est. $8-12 million).

A second de Kooning (Ames collected artists in depth and five de Koonings were offered in the sale), “Untitled” from 1976-77, an exuberant oil on canvas juicily painted in de Kooning’s bravura brushstrokes, realized $10,362,500 (est. $8-12 million). This one carried a third party guarantee.

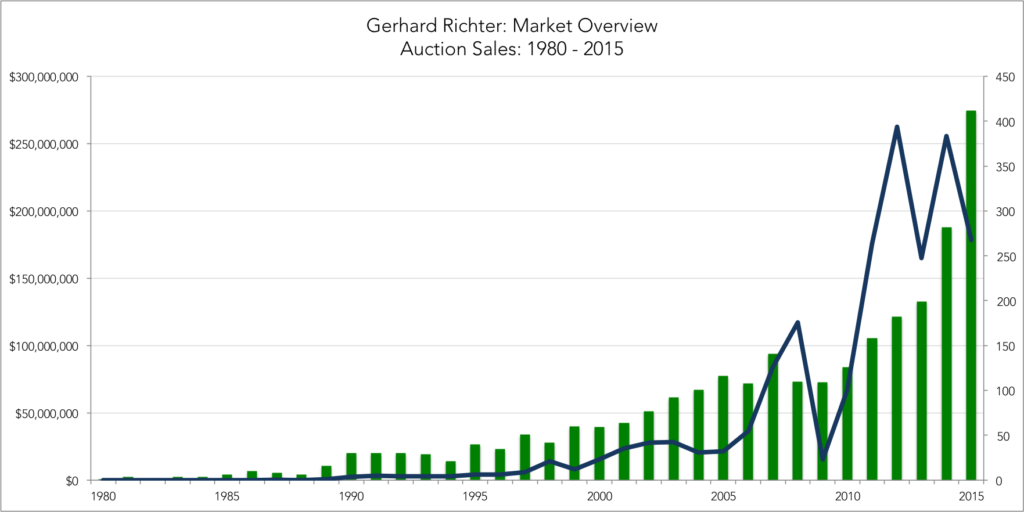

But the high-wattage heart of the Ames offerings was a group of seven Gerhard Richter paintings, led by the luminous “A B, Still (612-4)” from 1986, measuring 88 ½ by 78 ¾ inches, lushly painted in a fiery palette, which fetched $33,987,500 (est. $20-30 million) and went to an anonymous telephone bidder.

It became the most expensive Richter to sell this week, no small feat.

Ames acquired the painting at Sotheby’s New York in 1991 for $264,000, four years after it debuted in New York during ground-breaking joint exhibitions at Marian Goodman Gallery and Sperone Westwater.

Richter’s “A B, St. James” from 1988, featuring a darker palette and scaled at a wall-challenging 78 ¾ by 102 inches, sold for $22,737,500 (est. $20-30 million).

This squeegee-applied Abstrakt Bild debuted at London’s Anthony d’Offay Gallery in 1988 in the exhibition “Gerhard Richter: The London Paintings” and is one of a handful of abstracts with known place names, all evocative of British architectural monuments. Ames acquired it from d’Offay in 1989.

Both of the big Richters came armed with irrevocable bids.

There are so many variants and price points of Richter abstracts — an oeuvre that is meticulously documented in his online catalogue raisonné — that it can be difficult to distinguish the great from the not so great. But it would be fair to judge these two works in the former category.

Though the deliberately blurred photo-realist works from the artist’s massive “Atlas” archive, formally known as photo paintings, used to be more desirable than the later and more decorative abstracts, Richter’s “Familie Hotzel” from 1966, depicting a happy looking German couple posed outdoors with their young son failed to sell at a chandelier bid $1.9 million (est. $3-4 million). It was the only casualty in the Ames trove and came backed by a house guarantee, meaning it becomes the property of Sotheby’s.

The Ames’ group collectively made $122.8 million against a combined pre-sale estimate of $93.65 to $138.05 million.

Nigerian born painter Njideka Akunyili Crosby’s “Drown” from 2012, a 60-by-72-inch work in acrylic, colored pencil and solvent transfer on paper, was the first offering in the various-owners segment of the auction. It was chased by at least four bidders and hit a record $1,092,500 (est. $200,000-300,000).

Crosby’s paintings, represented by London dealer Victoria Miro, are impossible to buy on the primary market, since the gallery restricts sales of the red-hot artist to museum collections.

Her rich and sensual works, which often use family photos and draw on African current events — and on the artist’s great draftsmanship — are hard to beat.

Mark Bradford’s large-scaled “Let’s Make Christmas Mean Something This Year” from 2007, multi-layered in mixed media and collage on canvas, drills into the artist’s L.A. neighborhood with fragments of posters from local merchants. It made $4,737,500 (est. $3-4 million). New York/London dealer Daniella Luxembourg was the underbidder.

Christopher Wool’s black-as-night, patterned abstraction, “Your Sweetness Is My Weakness” from 1995, in enamel on aluminum panel, sold to Andrew Fabricant for $6,762,500 (est. $4-6 million), while Cy Twombly’s elegantly scribbled “Untitled (Bolsena)” from 1969, in graphite, wax crayon and felt tip pen on paper, brought on a cascade of bidding and made $2,952,500 (est. $1-1.5 million).

Graffiti of a different sort covers Jean-Michel Basquiat’s “Brother’s Sausage,” a multi-panel work in acrylic, oilstick and paper collage on canvas from 1983, which sold to dealer Jose Mugrabi for $18,650,000 (est. $15-20 million).

“I’ve been looking at that painting for a long time,” said the veteran dealer as he hustled out of the salesroom, “and I’m very happy to get it.”

Though never before at auction, the huge 48-by-187 ½-inch composition has wended its way through the galleries most of Basquiat’s major dealers, including Mary Boone, Bruno Bischofberger, Tony Shafrazi and Enrico Navarra, and has been included in many museum exhibitions, so there was no worry about its authenticity.

Basquiat’s peer Keith Haring, who also died young, was represented here by a rare “Self-Portrait for Tony” dated February 2, 1985 and dedicated to his dealer, Tony Shafrazi. Depicting the artist in his signature glasses, it sold to David Zwirner for $4,512,500 (est. $2.5-3.5 million) after a pitched battle.

“Two people really liked the image,” quipped Zwirner as he peeled out of the salesroom.

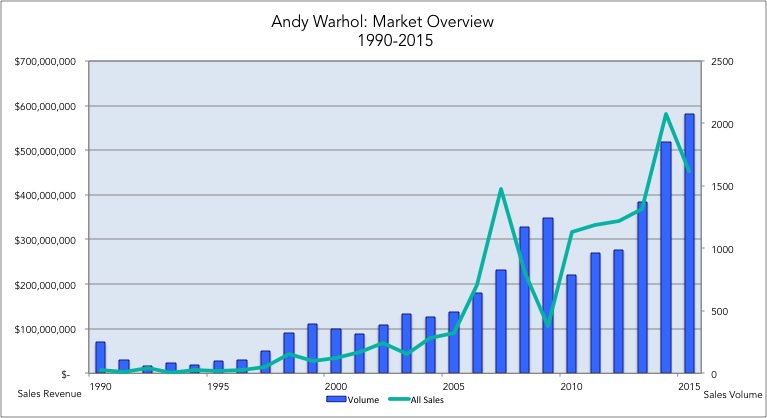

The larger scaled, potently familiar “Self-Portrait (Fright Wig)” by Andy Warhol from 1986, one of the last paintings completed shortly before his own untimely death, fetched $24,425,000, going to another anonymous telephone bidder (est. $20-30 million).

Though not the largest-scale work in the storied series — there are seven that measure 108 inches — the 80-by-76-inch canvas, with its white on black silkscreen ink palette, is distinctly haunting, seeming to portend death and disaster. It debuted as part of a series at London’s Anthony d’Offay Gallery in 1986, and last sold at Sotheby’s New York in November 1997 for $387,500.

Another late Warhol, “Lenin,” also dating from 1986, realized $8,112,500 (est. $4-6 million). The seller acquired the painting in 1987.

In a lighter tone, David Hockney’s mural-scaled country landscape “Woldgate Woods, 24, 25, and 26 October 2006,” an oil on canvas in six connected panels, sold to a telephone bidder for a record $11,712,500 (est. $9-12 million).

It carried a house guarantee and the seller didn’t own it very long, to put it mildly, having acquired the painting at L.A. Louvre Gallery in July 2014.

Thursday’s sale marked the end of a crowded week of high-stakes evening auctions that have allowed the houses a collective sigh of relief as the market nimbly soldiers on.

Remarkably, Sotheby’s tally on Thursday was almost identical to that of Christie’s Post-War/Contemporary Art evening sale on Tuesday, which made slightly more at $276,972,500, greatly helped by a $66.3 million Willem de Kooning painting — which stands as the most expensive Post-War lot of the week.