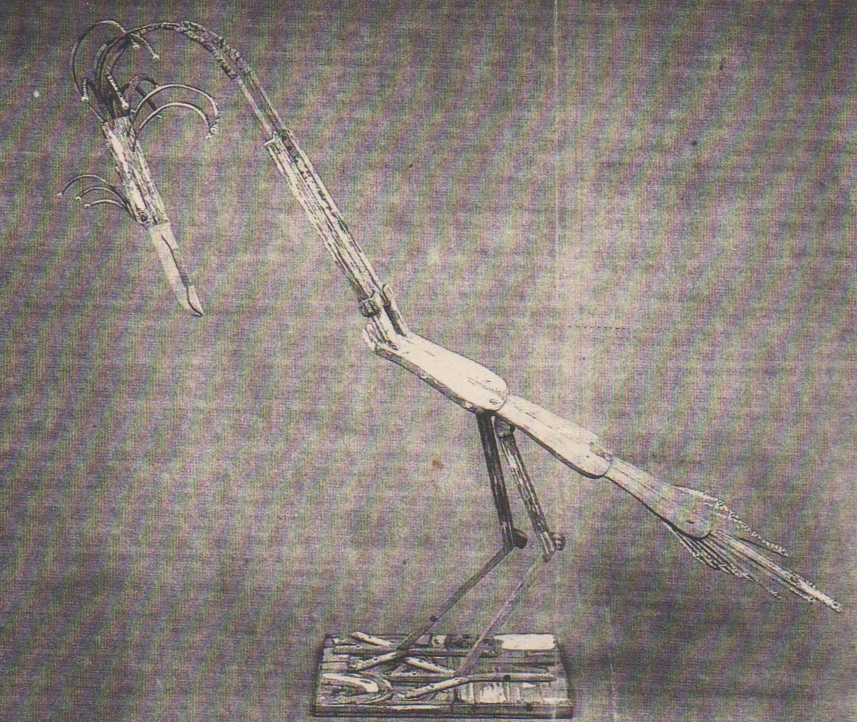

Margaret Wharton. Swan Lake, 1982. Wood, metal. and beads, 621/2 x 711/2 x181/2″. Courtesy Phyllis-Kind Gallery

The sculptural alchemy practiced by Margaret Wharton with a plebian cast o7-worn wood chairs surges skyward with obsessive thrust. Her sphinx-like characters appear dangerously fragile yet possess a spider web strength. As if the artist were ripping up layers of linoleum from a kitchen floor, the chair’s buried surface gradually emerges with a texture smooth as seawashed stones.

Swan Lake curls her long Art Nouveau neck for a hungry look at the pond beneath her. A fat, pearl-shaped eye scans the surface for a fish to pluck with her handsome beak. This ruffled creature wouldn’t stand a chance in the Everglades but the ballerina-like grace of her lines is impossibly seductive. The frozen gesture of the craned neck and ever-vigilant eye projects a surreal humor. Up close, the skin appears stripped with Red Devil

solvent, revealing a faint blush of green, a ribbony shard of white pigment.

In 1888, Van Gogh made two extraordinary paintings of chairs at Arles, Van Gogh’s Chair and Gauguin’s Chair. The former supports a pipe and tobacco pouch on its otherwise unoccupied rush seat; the latter, a lighted candle and two books. Despite the absence of human form, the two chairs speak volumes on their off-stage sitters. The compositions rattle the poltergeist of two powerful personalities. Wharton springs off the tension of Van Gogh’s gesture and transforms the anatomy of a chair—the back, seat, legs, and arms—into a new creature.

Victoria casts a haughty shadow. Diagonal rows of colored stone baubles are regally ensconced in a white plaster skin. The plaster great coat stops willy-nilly below the seat, showing a modest bit of leg. The pinched waist of the sculpture suggests a whale-bone corset has been engaged to keep her hourglass figure. Pompon-shaped tiaras fringed with plastic strands of pearls crown the piece, a last bit of icing in an already crowded parlor. Victoria is sassy but her encumbered posture—dictated by the era—restrains her movements.

Wharton’s dazzling choreography refuses to sit still. A springwound tension ticks inside of each incomparably mannered piece. 4 Horses lope across the gallery wall, their Pompeii pink flanks glistening with sweat. The tissue-thin depth of the racing mustangs can be moved like pieces on a chessboard or interpreted as animated hieroglyphics punctuated by wind-blown clumps of sagebrush. The expressive charge of the horses belies their true provenance: the muttish shank of a kitchen chair. The bandsaw wand of Wharton forges a new pedigree, literally out of this world.

In 1969 Lucas Samaras embarked on a series of chair transformations, incorporating mirrors, drawers, chicken wire, yarn, pins, plastic flowers, cotton, and Corten steel. H.G. Wells, writing in “First and Last Things” (quoted by Kim Levin in the Samaras monograph, 1975): “Think of armchairs and reading chairs and dining-room chairs and kitchen chairs, chairs that pass into benches, chairs that cross the boundary and become settees,

dentists’ chairs, thrones, opera stalls, seats of all sorts. In cooperation with an intelligent joiner I would undertake to defeat any definition of chair or chairishness that you gave me.” Wharton has embraced Wells’ Quixotic manifesto with an analytical bear hug. She constantly crosses the boundary Wells alluded to, dismantling, reconstructing, whipping into shape her metamorphosized beauties.

Earrings sway from heavenly lobes, creating a geometric traffic jam of Mondrianish lines. Pinpoints of light dance inside translucent stones, encased in the harlequin-patterned skin. The sushi chef precision of the assemblage produces astigmatic mayhem. In erector set fashion, each sliver of chair has been numbered and lettered for construction. These tattooed elements remain visible on the skin, as if to remind the viewer of

the process, dissection, and transformation.

Arman (the pack rat king of France) fileted violins and mounted them on panels. Virtuosity (1961) is uniformly sliced, like duck to go in a Chinese rice shop. Wharton brushes past Arman’s guillotined instruments with a brief nod of acknowledgment. But she continues to tinker, tune, and turn inside out her house of cards.

The photographic work—with a room of its own—is equally inventive (and less expensive). The chair is the thing. The star. The Houdini shackled in plastic, embedded in a block of ice, and photographed under klieg lights.- The 40x 30 inch C-print are silvery fields of emulsion, a cratered lava flow. They possess a blurred clarity, a kind of impressionistic Rorschach blot. Sea Urchin #2 bears the obvious form of an armchair floating in a sac of jet black ink. The surrounding surface shimmers with the mirage of etched aluminum.

Samaras Relief #2 is a glittery homage of sequined flotsam Jetsam. Clusters of multi-colored spangles cling to the collaged armchair in a magnetic trance. At center stage, Aerial Countess swings with abandon from her slender brass perch, biding her time before leaping into the arms of the alchemic Joiner.