Jean-Michel Basquiat

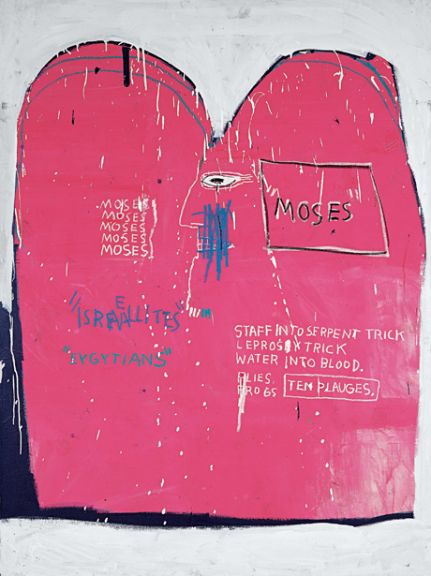

“Moses and the Egyptians,” 1982, Acrylic and oilstick on canvas, 73 x 54 in (185 x 137 cm), Guggenheim Bilbao Museoa; Gift of Bruno Bischofberger, Zurich. © The Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat / Licensed by Artestar, New York

In a major and carefully tuned gallery exhibition titled “Words Are All We Have: Paintings by Jean-Michel Basquiat,” opening May 2 at Nahmad Contemporary, the artist’s poetry-laced, word-saturated oeuvre is vividly unfurled in a grand manner, with some 25 paintings dating between 1982 and 1988.

Not since Gagosian staged “Jean-Michel Basquiat” in 2013, with around 50 works from public and private collections, has a gallery gone the distance to showcase the intellectual brilliance of the Brooklyn-born artist who was as obsessed by the likes of jazz great Charlie Parker and boxing legend Jack Johnson as he was by the meandering Beat lines of poet William Burroughs.

As a kind of illustrated adjunct to the Brooklyn Museum exhibition “Jean-Michel Basquiat — The Unknown Notebooks” from 2015, the text driven tapestry of Basquiat’s practice leap off the walls at Nahmad at a high-decibel volume. Guest curated by Basquiat scholar and serial exhibition organizer Dieter Buchhart, the paintings create their own jazz infused, hip-hop style music where words rule.

In “CPRKR,” 1982, executed in acrylic, oilstick, and paper collage on canvas and mounted on tied wood supports, the painting’s title crosses the top of the canvas in large block letters, created in custom shorthand style, sans vowels, in homage to Charlie Parker.

It is evident, judging by the early date, that Basquiat had already created his pantheon of black artist and athlete giants, with Parker representing, in almost chilling fashion, the genius and tragedy that would strike Basquiat down in 1988 at the age of 27. The rest of the canvas projects the familiar, three pointed crown that hails Parker as a kingly figure and the biographic note of the saxophonist’s gig at the Stanhope Hotel, dated April 2, 1955, that consumes another three lines on the canvas.

It doesn’t matter that Parker actually died on March 12, 1955, in a suite at that hotel, apparently of a heart attack at age 34, because Basquiat’s funereal homage, even with the sketchy bio, demolishes plain facts.

The painting is owned by artist Donald Baechler, no doubt acquired decades before Basquiat’s work blasted to the seven- and eight-figure mark, and is especially appreciated in that Baechler has been able to hold on to the work and resist secondary market temptations.

The fusion of great African-American figures packs a powerful punch, as evidenced by “Jack Johnson,” 1982, in acrylic and oilstick on canvas. The first black heavyweight champion, Johnson was a charismatic figure and a true giant of 20th-century sport, winning the world title in 1908. Here, in deceptively simple fashion, the stick figure boxer is crudely posed with one arm raised in triumph under Basquiat’s floating crown while his name, painted in black capital letters, anchors the base of the composition. The stretched canvas, purposefully slack at the edges to give the work a kind of wrinkled, unmade backdrop, delivers the knockout punch.

It hangs next to another boxing themed work, “Jersey Joe,” 1983, with the heavyweight champ’s full ring name, Jersey Joe Walcott, block painted in white against a blood red background. Unlike the sole figure in the Jackson piece, this composition features two stick figures, one of them getting punched in the head.

Basquiat’s special and unruly spelling for most things stands out through the exhibition, as seen in “Moses and the Egyptians,” 1982, again in acrylic and oilstick on canvas, with the tablet inscribed composition spelling out “ten plauges” and listing some of Moses’s greatest feats, such as delivering the “staff into serpent trick” and “water into blood.” Moses is repeated in block letters five times, as if it was a sort of punishing writing exercise on a schoolroom blackboard, though this one is hued in hot pink.

Again, the self-taught background of the artist is deliberately exaggerated with the misspelled words, bracketed by quotation marks, “Israallites” and “Eygytians.”

The 73- by 54-inch canvas belongs to the Guggenheim Bilbao Museum, a gift of Bruno Bischofberger, the first international art dealer to recognize Basquiat’s genius back in the early ’80s, when Neo-Expressionism boomed.

Among the artist’s greatest works here is the wobbly though round “Now’s the Time” canvas from 1985, another ode to Parker and his 1948 composition and album title. Shaped like an old-fashioned black vinyl record, it skewers a wall and says it all.

There is so much to learn about Basquiat in these paintings, even the seemingly mundane rap-like shopping or to-do lists as seen in “Eroica I” and “Eroica II,” 1988, borrowed from the Nicola Emi Collection.

There’s humor and drama in the grocery-like list mix, from “Ball & Chain: Wife” to “Bang: Injection of Narcotics” to “Bale of Straw: White Blond Female.”

Critic and curator Robert Storr at one time described Basquiat’s style as “eye-rap,” still a potent moniker for this deeply talented artist who blazed his own graffiti-bred trail.