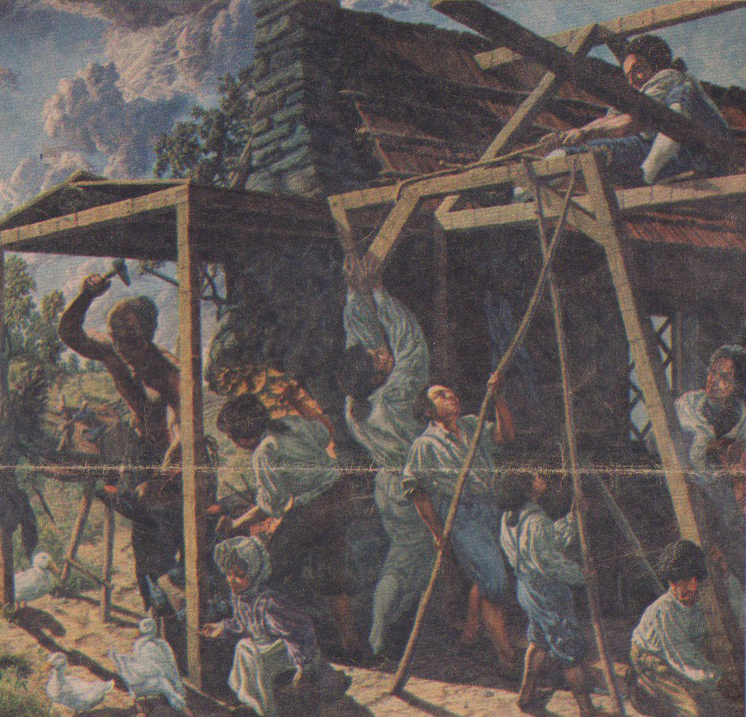

Colonization—Barren of any shelter, the scene at dawn vibrates with danger as two trappers barter with a nervous English Redcoat. His ship—and safety— is visible in the distance. Two children tend to the cooking at a campfire while their mother brings water in a bucket. At the left (Beal’s focius is always left of center) a woodchopper is poised to swing his ax against a virgin tree. Photographs courtesy of Allan Frumkin Gallery

The larger-than-life murals dominating the grand lobby of the new Labor Department, which were dedicated on March 4, came to birth in a thirty-one-month “Renaissance adventure” led by New York artist Jack Beal. His four is twelve-foot-three-by-twelve-foot-six panels are the first publicly funded paintings to be incorpocerated into the design of a federal building in Washington in thirty-five years. The return to realism in public art—the last example of the genre is Mitchell Jamieson’s 1942 tempera-on-canvas mural of Marian Anderson singing on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, which hangs in the Interior Department—is largely the product of the determination of Richard Conn, head of the Labor Department’s Bicentennial Office, and Beal’s own powerful persuasiveness.

Proud New Murals for the Federal Halls

For a generation government art has meant abstract sculptures and stabiles outside federal buildings, equally non-representational bas-reliefs and mosaic murals in the lobbies. But Conn wanted something else for the Labor Department’s new $95 million edifice that straddles Interstate 95 next door to the District’s Municipal Center. In a series of fierce drawings, mock-ups and memos, one of them running to eight single spaced, closely argued pages that concluded with a threat to resign the $150,000 commission if he didn’t get his way, Beal unfolded to Conn, to Donald W. Thalacker of the General Services Administration’s Art in Architecture Program and to the Visual Arts Committee Panel of the National Endowment for the Arts what that “something else” should be.

Settlements—A century later, on a summer noon, a hum of settlement is in the

air. The landscape bulges with new-planted fertility in this, the artist’s most

idyllic vision., The

woodchopper’s descendants, using more sophisticated tools,

are raising an addition to a house. The smithy’s forge, again left of center,

highlights the blacksmith and his apprentice with hammers raised in harmony. Photographs courtesy of Allan Frumkin Gallery

Beal’s alternative is a four-panel, four-century vision of the history of labor in America that has the ambience and style of Diego Rivera’s “Liberation of the Peon” murals in Mexico’s Ministry of Education and Thomas Hart Benton’s nine-panel depiction of “America Today” in New York’s New School for Social Research.

“The subjects for my paintings are not actual historical incidents or glorifying well-known heroes of the labor movement,” Beal said recently. “I drew people who were close to me but not celebrated or publicly recognized. The real heroes of American labor are everyday people working well and hard at their everyday jobs.”

The six-foot-four-inch painter sketched out his experiences in a series of conversations in the loft studio in New York’s Chinatown where he put the finishing touches to his epic work. Sprawled in an ancient easy chair in the eerie light of a winter afternoon, framed by the monumental panels that are—for the present at least—his masterwork, Beal rolled a pinch of Copenhagen snuff, snorted it, and declared:

“My whole painting career I’ve searched for an equitable balance between human needs and aesthetic need. It’s a very exciting conflict.

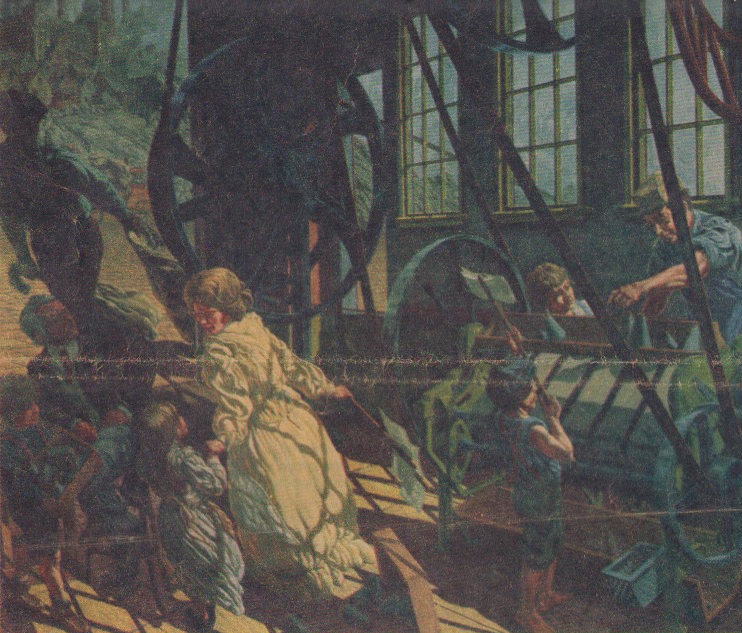

Industry—A strike protesting child labor is about to begin in the dimly lit textile

mill, where enormous belt-driven wheels brutally engulf the harried workers.

The industrialist, the only seated figure, looks on in impotent fury. Barely

visible through the smudge-specked windows is a ghost-like city of belching

chimneys. Smoke and filth are everywhere, gift of the mad dash to industrialize. Photographs courtesy of Allan Frumkin Gallery

“Clearly I’m a modern painter, but my interests are extremely varied and I try to draw stimulation from all kinds of sources . . . I’m making twentieth century pictures, but I’ve learned a lot from my sixteenth- anti, seventeenth-century colleagues.”

Then, in obvious anticipation of attacks by critics who see no place in contemporary art for representational

work, he continued: “I hate the phrase going back to realism.’ It’s like ‘going back to nature.’ We’ve never left nature. We’ve never left reality. I’m trying to paint people and things the way I think most people see people and things. And I’m trying to paint them as they are.”

When Walter Henry Jack Beal (He’s named for a “famous” uncle, the author of an Agriculture Department treatise entitled “Barnyard Manure”) speaks of his artist colleagues of the past, it is evident that they mean more to him than simply textbook techniques. The grand names sound like family friends as he expatiates on the exploits of Caravaggio, the intense discipline that characterized the working methods of Piero della Francesca and Masaccio, the family studio operated by Tintoretto. His self-identification with the great age of Italian public art is wholly unabashed. “We had to reinvent the Renaissance!” he exclaimed in one conversation. “I had to learn to draw all over again.”

In the face of the 848-day government deadline and the massive proportions of the project Beal envisaged (an average of nine life-sized figures in each panel), he had little choice but to revive the studio traditions of the heroes of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century art. Assisting Beal were his wife, Sondra Freckleton Beal, an accomplished water colorist, and two apprentices, Dana Van Horn and Bob Treloar, who at one time were students of Beal’s at San Diego State College.

Each morning the four would assemble for breakfast in the converted mill house that is the living quarters of the Beals’ farm outside Oneonta, New York, to discuss the day’s plan of attack. Then they would troop over to the studio that was specially built for the project.

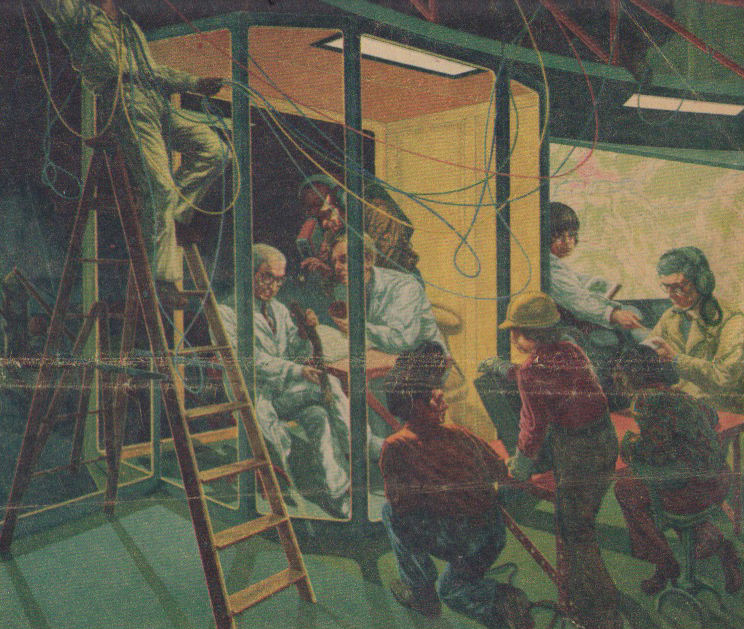

Technology—Night has fallen on the twentieth century, as white-coated technicians

study the relics of another age, one of them the branch that lies by the

campfire in the first panel. One technician (Jack Beal in self-portrait) fondles

a flower pot in which a tree seedling fights for survival. On another level, strands

of electrical wire graph the bondage (or is it liberation?) of man to technology. Photographs courtesy of Allan Frumkin Gallery

Because of the tension created by the huge area of stretched canvas only one person could work on a mural at a time. After the pastel preliminary drawings were scaled up by a grid system and transferred to the canvas, Beal made all the initial color decisions. Areas of dark and light colors were laid down by the group, while Beal did all the drawing and painting of figures.

“Jack never abdicated responsibility,” said apprentice Van Horn. “He made things so clear and established a spirit to work with and gave us a certain amount of responsibility to inspire us to give our utmost . . .”

The atmosphere at the studio crackled with creativity. Work went on far into the night, and ten-, twelve- and fourteen-hour days were normal occurrences. The only recreation beyond trips to the mailbox was lunch and dinner, which the crew cooked and ate together.

Van Horn, perched on a scaffold in one corner of the studio,would add meticulous detail to the bark of a tree in the seventeenth century mural. Periodically he would shift his gaze to study sections of bark collected on the farm that he had nailed to a nearby wall. Sondra Beal, hunched over a corner of the eighteeth century would paint from life—rocks, ducks and wooden beams. Treloar, assigned to the twentieth century, would bring in pieces of chrome and other metal for his panel’s laboratory section. “When there were problems,”

said Van Horn, “we had a little meeting and Jack would make the decision. Much of our work was repetitive. Once I learned how Jack wanted it done I generally repeated it. It took me a