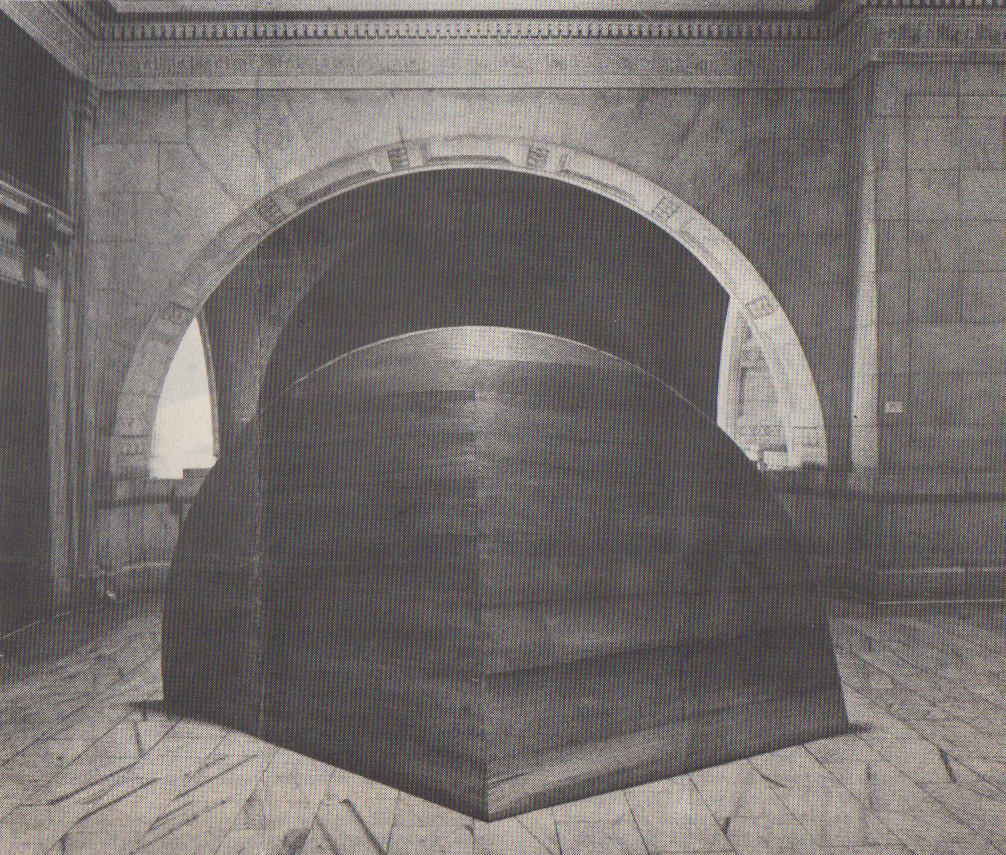

Martin Puryear, Her, 1979 pictured in “Custom and Culture,” an exhibition of new art and performance works sponsored by Creative Time, Inc.

A fluttering orange banner heralds Custom & Culture, enticing visitors to Cass Gilbert’s nautical palace, the former U.S. Custom House, on Bowling Green. For six weeks, sound installations, dance, music, and poetry readings will bombard the public under a 140-ton skylight dome that used to illuminate hordes of shipmasters fattening the U.S. Treasury. New works of art by sixteen artists have been spread throughout the twostory grand hall and elliptical rotunda, which measures 135 by 85 feet. Simply finding some of the art is more difficult than identifying the exotic shades of marble covering the columns, walls, architraves, and floors of this Beaux-Arts beauty.

Since the U.S. Custom Service moved to the World Trade Center in 1973, the seventy-tuna year old building has entertained mostly pigeons. The Federal General Services Administration has kept the physical plant in tune and has preserved the priceless set of frescoes executed 50 feet above the rotunda floor by Reginald Marsh in the fall of 1937. Artist Donald Sultan has seen fit to tease these eight trapezoidal panels with his “Eight Form Changes for Reginald Marsh,” fashioned out of paint, vinyl, asbestos, tar, and spackle compound. However humorous, his black-and-white images are hard to read and compete more with the peeling plaster that frames some of the murals than with the vibrant New York Harbor scenes that Marsh completed in a breathless ninety-three days.

Two closet-sized rooms e)rcavated by Robin Winters and appropriately named “Zetlith” and “Nadir” are described as “narrative installations.” In the Zenith room a red striped vintage war plane hovers over a caption: “The higher the flyer, the faster the sooner.” Across the hall in the Nadir room, a rendering of the same plane proclaims “We lost the last war.” Only slightly funnier is a picture of a bed creaking “Fuck Good” in the Zenith Room, while its Nadir deadpans “In Bed.”

Barbara Zucker’s “Use and Reuse” occupies the same space as a portion of the Museum for the America Indian installation last fall. Monochromed in Louise Nevelson black and mounted behind thin sheets of suspended plexiglass, pedestals support old-time cash registers, paper spikes and crumpled sheets of carbon paper. Black chairs and desks cover the similarly toned gravel floor; a single file cabinet with one drawer open is an evocative metaphor for the past glory of the Custom House (which at one time housed 1,700 workers). A soft spoken tape reels off architectural details and inner office statistics of bills of lading cargo.

Using the same staple (surplus wood desks), Lucia Pozzi has created a radically different atmosphere in the Old World posh of the Collector of the Port’s corner office. Playing with the elaborately coffered ceiling, Pozzi positioned four desks in a single line that spans the length of the room; their tops are covered with lushly tinted sheets of metal acetate. Entering the room, the visitor is dazzled by the natural light that molds with the shimmering turquoise, purple, green, and gold mirrors. However, framed photographs sit on the desks like sore thumbs, cluttering the effect. One depicts a leggy model cavorting on a ship-bound bed of mail bags, circa World War II. Another features a Vietnam-era body bag gingerly lifted from a helicopter, while a third shows a crew-cut customs agent gloating over a haul of what look like loaves of opium cloaked in aluminum foil.

None of the sixteen artists is more nautically attuned and architecturally sensitive than Martin Puryear. His red-cedar and douglas-fir sculptures, “She” and “Her,” installed at opposite ends of the mezzanine at the foot of flying spiral staircases (only the west staircase is accessible), lob salvoes of dialogue across the space. “She” is the aggressive one; “Her” is slower and more contemplative. Both appear to be inverted boat hulls that mirror the space they occupy. The two are perfectly aligned so that a visual line can be drawn through the links of chain that support the mammoth bronze lamps that span the Grand Hall.

Custom and Culture at the Custom House (a National Register Property and a designated New York City landmark) continues through June 17 and is open Wednesday through Sunday from 11 am to 6 pm. The experimental series of free art events received public funds from the New York State Council on the Arts and the NEA. Judd Tully