Ark, 1985. Oil on canvas, 63 x 90 inches. Photo: Sarah Wells

Medrie MacPhee was born in Edmonton, Alberta in 1953. In 1976 she received her B.F.A. from the Nova Scotia College of Art & Design. This was followed by further study in New York at the School of Visual Arts and the Cooper Union School of Art, and at the Banff Centre of Art. Since that time, she has taught at both Banff and Nova Scotia. MacPhee currently resides in New York.

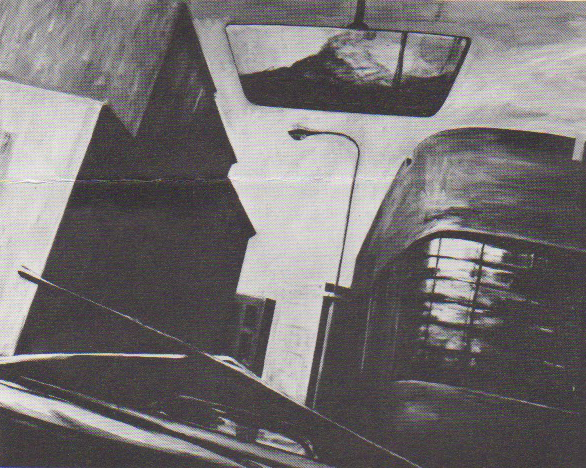

During the spectacular chase scene in the 1968 film Bullitt, Steve McQueen roars over the steep hills of San Francisco in a souped up Mustang. The cinematic view through his car windshield keeps you at the edge of your seat, anticipating a terrific crash. A similar sense of impending disaster occurs while viewing Medrie MacPhee’s Drive. The architecture seen through her “windshield” is bleached of detail. The location is anonymous. Trapped inside this view, pinpointed by the insect-like arms of the crossed windshield wipers, a scene is memorized. The bulk of plain facades loom up in a hallucinated mix of classical Italian architecture and metallic-toned Bauhaus. Glass brick windows reflect a moody sky and the roof line mimics the crenelated battlements of a castle under siege. The perspective is impaled on a long-necked street lamp with one alien eye. The car’s rear view mirror—icon-like at the top centre of the picture—projects the smoky reflection of a volcano. That split between the rear view mirror landscape and through-the-glass cityscape creates a chilling tension. Up ahead is another car and the filmy outline of a passenger. The narration stops. The image freezes. The mystery remains.

Drive, 1985. Oil on canvas, 70 x 90 inches. Photo: Sarah Wells

MacPhee’s demonic vocabulary of windows, arches and slashing chiaroscuro express with paint an existential vision tinted with a subdued surrealism. The shadowed piazza in De Chirico’s Delights of a Poet is a springboard to her deserted metropolis. Alienation reigns, reinforced by the visual shock of concrete landmarks spiked with iron fire escapes. Often the views look skyward, in an attempt to escape the monotony of the sidewalk. This too is frustrated by the verticality of the city, the omnipresent towers that block the sun and create their own shadows. It is easy to imagine the artist stalking the street, swiveling her head upward, losing touch with the ground. What you see on canvas is fiction tempered by memory.

The neck-arching vista of Channel for Piranesi is a high-rise bridge between two buildings. Architectural decoration has been stripped, its copper skin abandoned in favour of no-frills

windows. Whether that scene comes from the archway of Gimbels on West 32nd Street in Manhattan or the Bridge of Sighs in Venice is not important. Perhaps the two distinctly different places merged in the mind’s eye of the artist—a deep-seated internal view brought out into the light.

It is tempting to mention the American Precisionists of the 1920s and 1930s in searching for a hook to MacPhee’s paintings. Charles Demuth’s My Egypt, Charles Sheeler’s photograph of the Ford Plant, Criss-Crossed Conveyers and Paul Strand’s Apartment House, New York capture some of the geometric ferocity found in MacPhee’s paintings of the city.

It is not too great a leap from Edward Hopper’s fire hydrant and candy-striped barber’s pole in Early Sunday Morning to MacPhee’s street lamp and rooftop water tanks in Ocean Sky. However all of these references tend to fade close-up. The paintings do not romanticize the industrial landscape. They are not odes to concrete or the miracle of sodium vapour lights. Her vision is darker. Although the sky is still blue and painted passages take your breath away with a wisp of pink sunset, the images remain uncomfortable and menacing. They put you off balance. Thoughts of neutron bombs and suicide car bombers do not escape imagination. Even when MacPhee takes you out of the city or at least to a shipyard dry dock or vacant grain elevator, the verticality of ladders and derricks remain, the

never ending climb up metaphoric rungs stamp the landscape.

MacPhee rarely depicts human presence. A woman’s hand grips the steering wheel in Channel for Piranesi but that is as far as the artist goes in presenting physical form. Her pedestrian icons project a humanism that touches on religious feeling. A bug-eyed street lamp with a street sign fixed at the top becomes an anodized cross. To the city dweller the images are at once totally familiar and alien. It is difficult to tell if the atmosphere is breatheable. The unfinished hull in Ark with its scaffolding of upright ladders suggests a call for Noah. There is no line up of animals or shepherds in the wings. A whistle has blown to clear the set. Retracting that impression, projecting a calamitous oil spill at sea, the massive iron hull waits for repair. Whether it is restoration or reconstruction, the hull bears down on the viewer with a terrific weight. Anchored in shallow water, surrounded by a phalanx of ladders, the craft waits for a human touch.