In 1942 when the Art Institute of Chicago, the proud owner of Grant Wood’s best-known’ painting, “American Gable,” mounted a memorial exhibition of his work; local critics pounced with drawn daggers. “For a man who lived so close to the soil,” fumed a newspaper critic, “his landscapes are remarkable for their lack of emotion. There is no atmosphere. No smell of the soil, no wind in the air.”

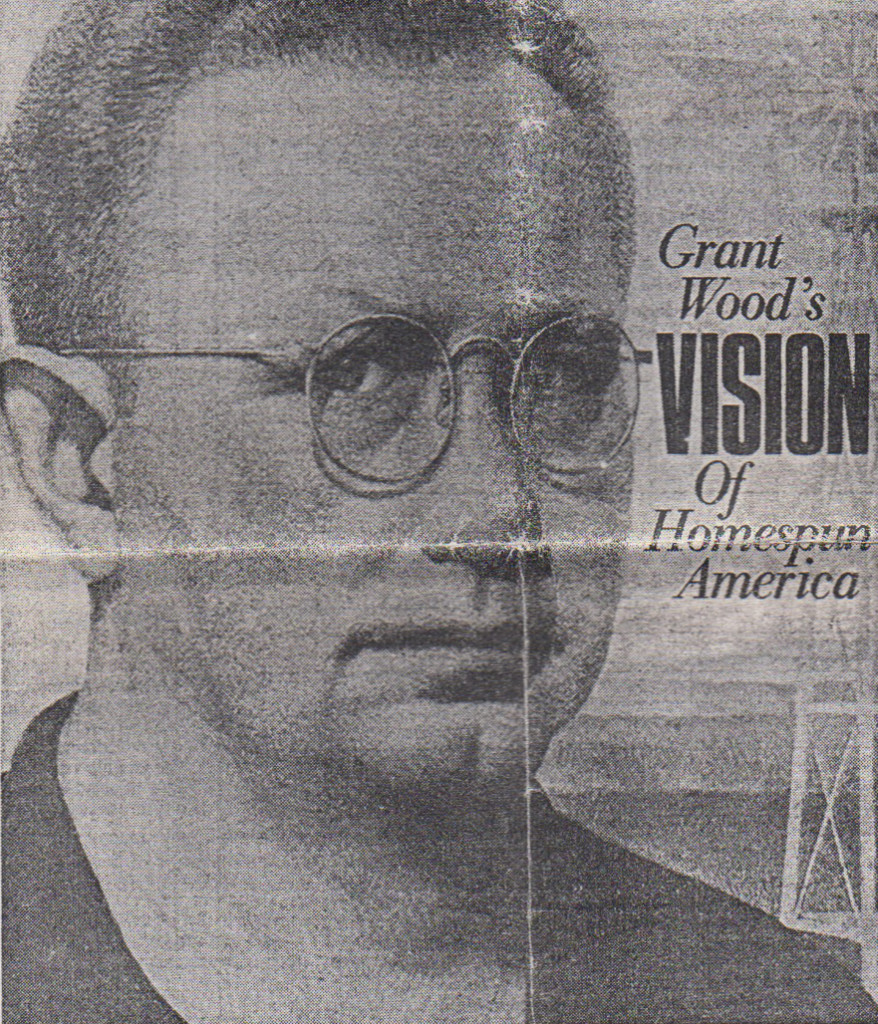

As usual,. Grant Wood’s art, even after his death — on the eve of his 51st birthday, in 1942 unleashed a hailstorm of controversy. The critics and the public had yet another chance to view the visual icon maker of the Midwest when the exhibit, “Grant Wood: The Regionalist Vision” opened last June at New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art, then . traveled to Minneapolis and Chicago. It will now go on display at San Francisco’s M.H. de Young Memorial Museum next Saturday.

Organized by Samuel Sachs H, director of the Minneapolis Institute of Arts, and guest curated by Stanford’s Dr. Wanda Corn who prepared the excellent catalog, the 90 paintings, drawings and lithographs that span two world wars.

Grant DeVolson Wood was born to Quaker parents on a farm near Anamosa, Iowa (population, 2000); in 1891. His father, Maryville, is quoted in Wood’s unpublished memoir (titled “Return from Bohemia”) as saying, “It’s good to have him chunky. He’ll make a good farmer.” The memoir ends in 1901 after his father’s death, when the young widow, Hattie Weaver Wood, sold the farm and moved with her four children to Cedar Rapids, 30 miles away.

Grant’s passion for drawing Plymouth Rock hens and the “brilliant stripes of garter snakes against the black soil” did not abate. But the trauma of leaving the farm that Maryville built and nurtured for the modernity of indoor plumbing and daily mail delivery left a profound impression on the boy in the faded blue overalls. Yet he resolutely pursued his art, winning a 1905 national Crayola contest with a chalk drawing of oak leaves, designing sets in high-school plays, and contributing illustrations to his senior yearbook.

Intrigued by the Craftsman, a major art magazine of the early 1900s, Wood was particularly interested in the writings of architect-writer Ernest Batchelder, who was especially fond of “constructive logic” and Gothic cathedrals. Batchelder’s illustrated essays gave Wood a razor-sharp knowledge of masonry and geometry and whetted the teenager’s appetite for more In 1910, fresh out of high school, he rode a train to Minneapolis to study first-hand the eclectic style of Batchelder at the Minneapolis School of Design and Handicraft, where he developed a sophisticated vocabulary in design.

In 1923, he arranged a sabbatical from his public school teaching post and embarked on a painting trip to Europe. But his frustrating experience as a student at the Academie Julien in Paris (his teacher held his carefully mixed water colors under the faucet to get them sufficiently runny) and a disappointing first show in a Left Bank gallery in the dead of Parisian summer took the wind out of his European sails. On returning to Cedar Rapids, he moved with his mother into his first studio.

But Wood was destined to return to Europe one more time — to supervise completion of a stained-glass window commissioned by the city of Cedar Rapids for the Veterans Memorial Building. During the three month Munich sojourn, Wood saw the vision-shaking Flemish paintings of Hans Memling, Albrecht Durer, and Pieter Brueghel the Elder at the Alte Pinakothek Museum, a Louvre-scale palace with 20,000 paintings. These Renaissance-era masterpieces, studded with architectural and costume detail, wove simple tales around Biblical themes, mirroring the changing seasons and everyday toil of God-fearing people.

Wood must have also viewed — as suggested by the late art historian, H.W. Janson — the contemporary Munich art scene dominated by Otto Dix and George Grosz. They championed “neoobjectivism,” a painting credo based on an “unswerving faith in positive, palpable reality.” Their brutal yet hilarious cafe and brothel scenes were both nationalistic and loyal to the roots of German painting, yet dead set against the gusting currents of Paris-inspired cubism. The doubleshot of 15th and 20th century Gothic influence propelled Wood back to his roots in Iowa, the black soil and hard-edged spirit of the Corn Belt. He never again had to look back.

By the late 19205, Wood had abandoned his “wristy,” impressionist brush strokes of bucolic scenes — imported from France — for the sharply focused, hard-edged realism, laced with wit, that became the hallmark of his modern style. His long-marinating break with Bohemia was in part orchestrated by the strong advice of his friend and mentor, the insurance selling poet, Jay Sigmund, to paint the clotheslines in his own back yard and leave the wishy-washy doorways of Europe behind.

Eager to try out the ideas he had been exposed to in Europe, Wood painted a startling portrait of his 71-year-old mother in 1929, which he called “Woman with Plants.” Grant Wood was still fiddling with his new style in “Woman with Plants,” and the uninspired landscape elements wilt under the weight of the mother.

“Stone City,” painted a year later, soared above the flattened landscape of “Woman with Plants.” Wood’s perspective rose like a hot-air balloon, delivering a breathtaking vista of the sculpted countryside. Stone City was in fact a bankrupt quarry town, and Wood painted the roller-coaster hills and trees that resembled helium-filled brussels sprouts in hypnotic rhythms. The modestly efficient windmills, the suspension bridge and the freshly planted rows of corn ticktock with a master-watchmaker’s precision.

Grant Wood’s classic “Daughters of Revolution”, Ever the regionalist.

Wood also painted “American Gothic” in 1930, recruiting his sister Nan (then 30) and his dentist, Dr. B. H. McKeeby (age 62), to pose. The two stand stiffly before their prim homestead, ready to take on all comers without budging an inch. The composition is a reflecting pool of vertical patterns, bouncing from the sun-glistening tiries of the upright pitchfork to the scrubbed-out shine of the seams in the farmer’s faded overalls. A Sunday preacher and his spinster daughter, they stare with mouths clamped tight as clams.

Despite four Bohemian forays to Europe in the 1920s, Wood remained a home-town artist, beloved in Cedar Rapids but obscure outside the manicured city limits. The 43rd Annual Exhibition of American Paintings and Sculpture at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1930 changed all that. After a considerable tussle in committee, “American Gothic” was not only accepted for exhibition but also awarded the Norman W. Harris bronze medal and the $300 prize. The painting of the scrawny couple with a pitchfork created a cross-country media sensation and punted the 39-year-old dimple-chinned artist to overnight fame.

When the Des Moines Register reproduced “American Gothic” but erroneously captioned the picture “Iowa Farmer and Wife,” a salvo of incensed letters to the editor bit the state capital’s premier newspaper. One published letter set the record straight: “When Mr. Wood asked me to pose for him,” wrote the unspinsterish and marcel-waved Nan Wood Graham, “he showed me some pictures of old Gothic stone carvings from a cathedral in France and asked if I could pull my face out long and look like some of the women in the carvings I told him some of my neighbors looked like that just naturally, but he explained that he couldn’t ask them to pose without hurting their feelings, so I gladly consented and still consider it a great honor.”

The electrifying success of “American Gothic” baffled Grant Wood, but his self-confidence bloomed enough to write Juliana Force, the feisty director of the brand-new Whitney Museum of American Art, then located on West Eighth Street in New York. In perfect-penmanship script, Wood wrote, “I am working diligently, but paintings in the style of ‘American Gothic’ and ‘Stone City’ necessarily take considerable time in the making.”

To illustrate his point, Wood shipped the freshoff-the-easel “Arnold Comes of Age” and “Stone City” to New York. A month passed before Force’s typewritten, single-spaced reply of January 24, 1931, was received: “It is our unanimous opinion not to purchase them at this time, but will consider again including one of your paintings in our collection. am returning the two pictures to you, express prepaid. Thanking you again…”

“It was just one of those things that happened,” mused Lloyd Goodrich, the 86-year-old director emeritus of the Whitney and widely published author of monographs on great American artists. Goodrich was the museum’s research curator at the time of Wood’s fizzled attempt to storm that citadel of art. “We didn’t go after Grant Wood,” Goodrich continued. “I know there was a low price on ‘American Gothic’ back then, because the Art Institute grabbed it for $300.”

To this day, the Whitney Museum — the august repository of American scene painting — does not own a Grant Wood oil. (They do have two studies of the dazzling triptych, “Dinner for Threshers.”) By the time Wood had a one-man show in New York at the Ferargil Gallery in the spring of 1935, he had been showered with laurels and his narrative imagery resonated his unique signature. The Roosevelt’s administration appointed him director of Iowa’s Public Works of Art Project that year, and he rode the college-lecture circuit, trumpeting his “Revolt against the City” views, while still finding time to marry Sarah Maxon (whom he divorced in 1939) and to move from Cedar Rapids to Iowa City, where he joined the art faculty of the University of Iowa. Time magazine saluted his efforts by crowning him “chief philosopher and greatest teacher of representational U. S. art.”

Among the Feragil gems, the “Birthplace of Herbert Hoover” (1931) flaunts Jay Sigmund’s teetering clothesline of Iowa-blown laundry, and a silhouetted gentleman in the foreground points proudly to the quaint landmark. “Daughters of Revolution” (1932) plasters a sour-faced trio of prim, tea-sipping patriots in front of Emanuel Leutze’s legendary “George Washington Crossing the Delaware” (1851). “Return from Bohemia” (1935) laid Wood’s regionalist cards on the table with a furrow-browed self-portrait, surrounded by an introspective cast of farmers.

Wood was lambasted in the left-wing pages of The New Masses for depicting only “rich, prosperous farms” during a depression-era slew of farm foreclosures, and was chided by Lewis Mumford in The New Yorker for being “a National symbol for the patrioteers.” But his paintings continued to sell — to film stars Edward G. Robinson and Katharine Hepburn, to Hollywood producer King Vidor and director George Cukor, to novelist John P. Marquand, and to publisher/department-store heir Marshall Field III. Cole Porter bought the tire-screeching “Death on Ridge Road” (now in the collection of the Williams College Museum), and Mrs. Boyce Gooch of Memphis snared the klieg-lighted “Midnight Ride of Paul Revere” (later sold to the Metropolitan Museum in 1950 for $15,000, now the only Wood painting in the collection of a New York museum).

After the mud slide of negative reviews from Wood’s Chicago memorial exhibit in 1942, Gooch huffed in a letter to Art Digest that the critic “was deaf to Grant Wood’s rate of vibration.” She should have been commended for her sensitive ear. Today, a major Grant Wood painting — if one were on the market — would fetch from $300,000 to a million dollars. The prices on these rare commodities have escalated to the point that museums have pooled their purchase funds to share a single painting. For example, the Minneapolis Institute of Arts and the Des Moines Art Center recently acquired the “Birthplace of Herbert Hoover” from a private owner at a whopping $500,000. “Adolescence,” Wood’s masterfully humorous pencil drawing of a gangly rooster book-ended by a pair of plumply feathered hens, also sold recently at Christie’s auction house in New York for $130,000, setting a record for 20th Century American drawings.

Grant Wood painted farmers behind horse-drawn plows, while Enrico Fermi split the atom. He satirized the fables of Paul Revere’s ride and George Washington chopping down a cherry tree, while waves of avant-garde artists unloaded their easels in New York and America prepared to dig out from its isolationist youth. Wood serenaded the public with his snake charmer’s gifts and carved a niche for his unique, deliciously homespun vision.

Long before historic preservation and American-folk-art collecting came Into vogue, Wood salted away an encyclopedia’s worth of American images — from Currier and Ives prints to Sears, Roebuck and Company mail-order catalogs — into his taut and maniacally detailed brush. His hand-ground blend of Quaker and Shaker tools and furniture, the patchwork quilts and tintype photographs, dripping with a Victorian chill, wended their way into his hit parade of paintings.

It is tragic that Wood died at 50, a victim of liver cancer. He had stretched his boundless energy to the limits, with public speaking, teaching and a prodigious series of book illustrations (including a stunning, limited-edition “Main Street”) and low-priced, mail-order lithographs printed by the Associated American Artists. But his easel paintings suffered and, even on his deathbed in the Iowa City University Hospital, Wood stubbornly spoke of painting a companion piece to “Woman with Plants,” a long-planned homage to his father, Maryville.

Because of the delicate condition of the oil-on-masonite surfaces and the constant pressure on museums (mostly in the Midwest) to display their Wood treasures, this new retrospective — which will be at the de Young through August 12 — will more than likely be the last one of this century. With the continuing ascent of American painting, the pictures of Grant Wood should be savored and meditated upon in this seemingly final journey.