Trial kindles sexual politics in New York’s art world

“My wife is an artist, and I’m an artist and we had a quarrel about the fact that I was more, eh, exposed to the public than she was. And she went to the bedroom and went in after her, and she went out the window.”

—Carl Andre’s taped 911 emergency call on September 8th, 1985

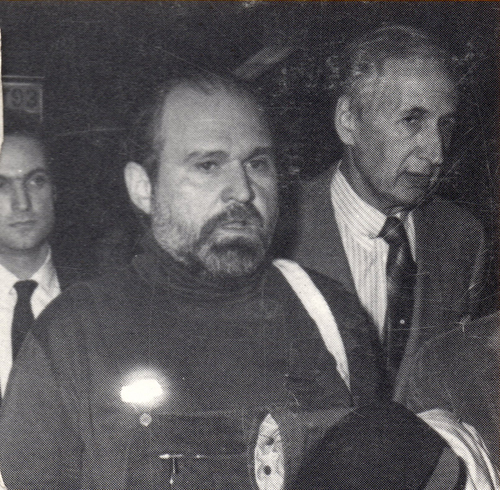

Carl Andre

Moments after New York State Supreme Court Justice Alvin Schlesinger intoned, “I am not satisfied beyond a reasonable doubt that the defendant is guilty,” thereby acquitting 52-year-old Minimalist sculptor Carl Andre of two counts of second-degree murder, Andre’s attorney, Jack Hoffinger, jubilantly cuffed his client on the back and Andre raced out of the courtroom, bundled in his down overcoat, a free man.

The two-week-long non-jury bench trial of People vs. Andre ended February 11, closing the tragic tale of sculptor Ana Mendieta’s death at age 36. Mendieta jumped, fell, or was pushed from the couple’s 34th-floor bedroom window in Greenwich Village in the dark morning hours of Sunday, September 8, 1985. Hoffinger successfully argued that the cause of her fall-270 feet onto the pebbled tarpaper roof of a 24-hour delicatessen—was either an accident or a case of subintentional suicidal technical term meaning “you can’t be sure if the person organized the suicide,” according to an expert witness testifying for the defense.

Andre never took the stand, and it was his decision to waive a jury trial. From the day the criminal case grabbed front-page headlines, Andre has not peeped a word to the press other than his acquittal comment, “Justice has been served,” uttered to a posse of reporters moments after the verdict.

The trial began the same week as Mendieta’s posthumous retrospective closed at the New Museum of Contemporary Art. Closing summations by defense and prosecution were delivered on the day Andre’s show opened in Madrid at the Palacio Crystal. The stark courtroom, the absence of a jury, and the distant presence of the bearded and blue-overalled defendant, who spent much of his courtroom time reading the New York Times or pinching the bridge of his nose, made a perfect Minimalist metaphor.

Throughout the trial, a group of women, many associated with the art world, dominated the prosecutor’s side of the spectator section, poised with notebooks, scribbling harder than the smaller contingent of courtroom reporters representing the Daily News, Newsday, the Village Voice, and El Diario. The New York Times showed up at the tail end of the trial and ran only two stories—the day before and the day after the verdict—surprisingly scant coverage considering the near art-star status of the defendant.

In ironic contrast, just down the hall from Andre’s courtroom, was the “preppie” Robert Chambers trial. The case surrounding the murder of 18- year old Jennifer Levin, the daughter of a SoHo realtor, attracted an all-channel, TV mini-cam vigil and daily front-page coverage. A police barricade and metal detector fronted that courtroom and spectators had to wait in line for admittance. As one veteran newshound commented, “It has everything—you know, sex, drugs and rock ‘n’ roll.”

The two cases were similar (the Chambers jury trial—at this writing—is still in progress) in that both victims were women and their drinking habits were scrutinized; both deaths occurred in predawn darkness; both men had fresh scratch marks on their faces; and both cases relied on circumstantial evidence and the expensive testimony of expert medical witnesses.

The two cases were similar (the Chambers jury trial—at this writing—is still in progress) in that both victims were women and their drinking habits were scrutinized; both deaths occurred in predawn darkness; both men had fresh scratch marks on their faces; and both cases relied on circumstantial evidence and the expensive testimony of expert medical witnesses.

But Andre’s days in court were scrutinized along feminist lines. In almost segregated fashion, women from all phases of the New York art world—painters, critics, curators, performance artists, and ideologues—watched the proceedings, giving the chilling impression that their lives were on the line. Andre trial spectator Nancy Berliner, who performed at an East Village club on Valentine’s Day night (three days after the verdict) a riveting performance poem based on the trial, put it this way: “When a woman goes flying out the window, you’re having an argument with your husband.”

The trial—in spooky fashion—also corresponded to the February line-up of shows at the Museum of Modern Art. “Committed to Print,” a rare political show with emphatic leftist leanings curated by Deborah Wye, included many of the women (and two male elders) who participated in the Andre trial, either as interested spectators or subpoenaed witnesses. One artist wryly commented that most of the museum staff and Rockefeller types were noticeably absent from the show’s opening.

By coincidence, a strike by MoMA’s in-house union, PASTA, drew the support of sculptor Louise Bourgeois in the form of a poster which read, “No No No No”—the exact words that doorman Edward S. Mojzis testified he heard a woman scream on that hot September night, seconds before the thunderous impact on the roof of the Delion Deli. The defense argued that the doorman at 11 Waverly Place—who suffered in the past from auditory hallucinations (but that came out later)—could not possibly have heard a human voice from 300 feet away, but flubbed that argument by calling in an unconvincing sound expert who tried to duplicate the conditions of the scream in wintertime, two and a half years later.

Another manifestation of MoMA’s paradigm of power relationships juxtaposed with the trial was guest curator Barbara Kruger’s show, “Picturing Greatness'” in the Edward Steichen Photography Center. On these 40 portrait photographs of artists in her signature, blown-up text in Constructivist colors—red, black, on white—Kruger writes, “. . . almost all are male and almost all are white. These images of artistic ‘greatness’ are from the collection of this museum . They [images] can show us how vocation is ambushed by cliche and snapped into stereotype by the camera, and how photography freezes moments, creates prominence and makes history.”

MoMA’s shadow dogged the trial. On the day of the verdict, moments before the judge announced his “reasonable doubt,” Andre was deeply absorbed in the front-page New York Times story announcing Kirk Varnedoe’s accession to William S. Rubin’s post as the museum’s director of painting and sculpture.

Kruger was a regular at the trial and, after the verdict, sprung a one-liner at the gaggle of reporters hovering at the swinging doors of the courtroom, “It’s the most press he’s gotten in ten years. He needs it for his career.” In a phone interview, Kruger said she was interested in law and that she lives a block away from the courthouse. “I’m interested in the literalization of power. You can see that in any trial you go to. I read a lot about what goes on in the world and this city, how law literalizes itself, and how it determines who we are in the world and what our positions are to a large degree . Who’s law is a client of and who it’s not a client of. The whole thing about law is how things function in a symbolic space . How narrative is the motor of every social furtherance.”

Ana Mendieta

In MoMA’s contemporary wing, the section reserved for still-living blue chip artists, Carl Andre’s Timber Spindle Exercise from 1964 squatted like a squashed Brancusi in a tight corner of the installation. Andre had a solo exhibition at the museum in 1973—seemingly an obscure point, except that much of the case seemed to hinge on the professional standings of the respective artists: the Andover Academy-educated Andre or Mendieta, the daughter of an aristocratic Cuban revolutionary who emigrated to the U.S. after the revolution (as part of a CIA program dubbed “Peter Pan,” to save children whose parents had fallen out with Castro) and wound up, along with her sister, in an orphanage in Iowa. The fact of Mendieta’s heritage was bandied about by the defense and its roster of witnesses to underscore her “fiery Latin temperament.”

“I found that truly offensive,” fumed one curator, insisting on anonymity. “The defense tried to turn Ana into the stereotypical, hot-blooded, drunken Hispanic.”

Painter and current Guggenheim fellowship winner Howardeena Pindell was much blunter when asked about the way Mendieta’s personality was brought out in the trial: “What they did was try to degrade Ana because she’s an artist of color. All that stuff introduced about her being interested in Voodoo, to show the judge she was ‘other’ and dragging out pictures of Ana with Castro in Cuba was an attempt to degrade her. The art world is segregated as it is. I know if Ana had been an Anglo and if Carl had been black, the art world would have lynched him… . Oh, sure, I see it as totally symbolic, your life isn’t worth shit, is that direct enough?”

There was intense speculation—some would call it a conspiracy theory—throughout the three grand juries and the bench trial that potential witnesses were terrified to testify for the prosecution because of potential art world repercussions. (Ida Panicelli, the new editor of Artforum, and the only establishment art world figure to testify on Mendieta’s behalf, testified that Mendieta’s career was ascending and that Andre’s had cooled.) Or, put another way, Ruby Rich, film critic and author of an incendiary Village Voice piece, “Remembering Ana Mendieta: The Screaming Silence,” which appeared one year after the artist’s death, commented, “The cowardice of the art world has been staggering.”

“All the talk about an art world conspiracy is paranoid nonsense,” said Jerald Ordover, the attorney who arranged the $250,000 bail that sprang Andre from Riker’s Island.

“People—you know, artists, writers, dealers—cautioned me not to testify,” said sculptor Marsha Pels, who was close friends with Mendieta in Rome where they both had Prix de Romes at the American Academy. “But so what? I couldn’t live with myself if I didn’t get involved. Perhaps I’m naive, but I didn’t think he was that powerful. I can’t be objective but while I was on the stand, he [Andre] acted as if the whole thing was a waste of his time. Yet he had the audacity to drag her through the dirt. I don’t know if I was more disappointed in the system or him.”

“The lawyering business is tricky,” mused artist Nancy Spero, a witness in

the trial. “You’re on the grill; it’s like entering a hospital waiting room not knowing what the doctor’s verdict will be. My aim was to be as honest as possible. It was quite common knowledge that Carl and Ana were heavy drinkers and that they had constant words with each other . . . A lot has not come forth but, even then, it would have been inadmissible anyway.”

“This was a very important case because it proved the system works,” opined Andre’s chief attorney, Jack S. Hoffinger of Hoffinger Friedland Dobrish Bernfield and Hasen, in a telephone interview. “I never comment why a client does or doesn’t take the stand. . . . As you may know, Carl Andre has never talked publicly, and I doubt whether he’s talked privately about this case with anybody. Carl is an extremely private person, as you may have guessed. He doesn’t want his picture taken—you can publicize his works, but you can’t talk about his private life. He won’t talk to you about it.” (Hoffinger was on the mark in this regard. Andre did not respond to a written request for an interview.)

“One of the horrors of this case,” continued Hoffinger, “is to some extent his life and her life were publicized, which is not something he wanted to do. He did not encourage any kind of denigration of Ana, in any way. He did not want that and we did our best to not go too far with that.”

Carlene Roach, the deputy director of public information in the District Attorney’s office, nixed an Examiner interview with Andre’s prosecutor, assistant district attorney Elizabeth Lederer. “We really can’t comment on the case. Criminal procedure law prevents us from giving out any information. It’s as if the case didn’t exist . .. all data has been expunged from the records.”

Lederer did tell this reporter—before the interview request was denied that fingerprints obtained during a search warrant of Andre’s apartment were ruled inadmissible because they went beyond the scope of the search warrant prepared by the D.A.’s office. Lederer said there were no footprints lifted from the dusted window, a fact that would seemingly discount half of the defense’s contention—that Ana jumped. The prints tap the heart of Fourth Amendment rights concerning unreasonable search and seizure.

“We’ll never know what happened,” said Robert Katz, screenwriter and author of Love is Colder Than Death, a biography of German filmmaker Rainer Werner Fassbinder. Katz is writing a book on the Andre-Mendieta saga. “The big story is how this remarkably disparate couple, coming from two different worlds, met on a collision course.. . . It wasn’t a great courtroom drama. The most intriguing part of it were the people who knew Ana very well and had to work by a process of elimination . . . they couldn’t believe she committed suicide. They couldn’t believe it was an accident . . . that’s what people got passionate about . . . Ana did a bloody performance piece on a rooftop once. But after it’s over the person gets up and walks away. Carl once wrote a poem and one of the lines is `she stood naked by the window waiting to be struck.’ But in the poem [written in 1958], the person was not struck. The woman just turns away in tears.”

The Andre trial is over. The tragedy of the story remains. Mendieta could not get up and walk away.

Judd Tully is a New York-based writer and critic whose writings often appear in the Smithsonian, Horizons, and the Washington Post. He is New York editor of the New Art Examiner.