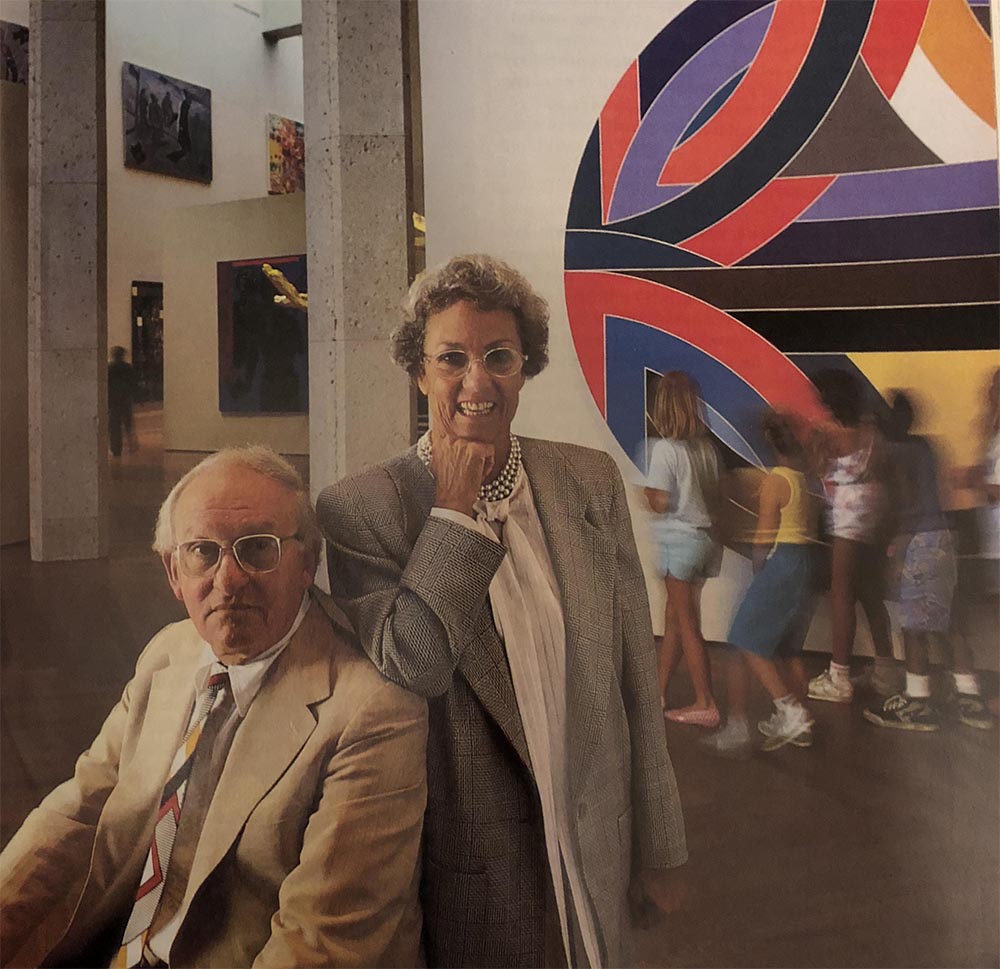

Sydney and Frances Lewis, at right Frank Stella painting

After a tentative start some 25 years ago, the Richmond couple, founders of Best Products, gained momentum and expertise.

In the early 1960s, Sydney and Frances Lewis of Richmond, Virginia, attended an auction in New York with their friend painter Theodore Stamos and bought—at Stamos’ urging—an anonymous French chest and a pair of side chairs. At the time they had no idea their spontaneous purchase would lead them into an entirely new field in their more than 20-year bout of collecting fever. And into an accumulation of art that would ultimately require a new wing back home at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts.

“I was intrigued by those lines,” recalls Sydney Lewis of that first piece of Art Nouveau bought at auction. “I can speak for me. I can’t speak for Mrs. Lewis.”

Before his next sentence emerges, Frances Lewis affirms “Absolutely. absolutely,” and charges seamlessly into the conversation. “Now stop we if I’m wrong,” Mrs. Lewis challenges with the arch of an eyebrow, “but we started collecting. for furnishing our house, like everyone else around here with 18th century English furniture, buying at auction, mostly in England. That lasted about two years.”

Interviewing the Lewises together at home or in their offices at corporate headquarters, one grows accustomed to getting compound answers to single questions. A longtime friend of the Lewises putsit this way: “SydneyandFrances is definitely one word. They kind of now together.” The Lewises are something of a down-home Medici family, keen on bringing the latest expressions of culture to the public. Their ability to do so has been fueled by the fantastic success at their showroom catalog enterprise, Best Products.

The beginning of Best Products Co., Inc., couldn’t have been more modest, the success more monumental. It was started as a mail-order operation in 1957 with a catalog printing of 1,000 and a warehouse from which to respond to hoped for orders. The orders came, eventually in flood proportions. Last year sales hit $2.2 billion. Eleven million catalogs were mailed, keyed to a network of 200 stores in 28 states; total showroom space is more than 5.7 million square feet, with that much again in warehouse space. The name came from a what’ll-we-call-it session between Sydney and Frances, who concluded that there couldn’t be anything better than best.

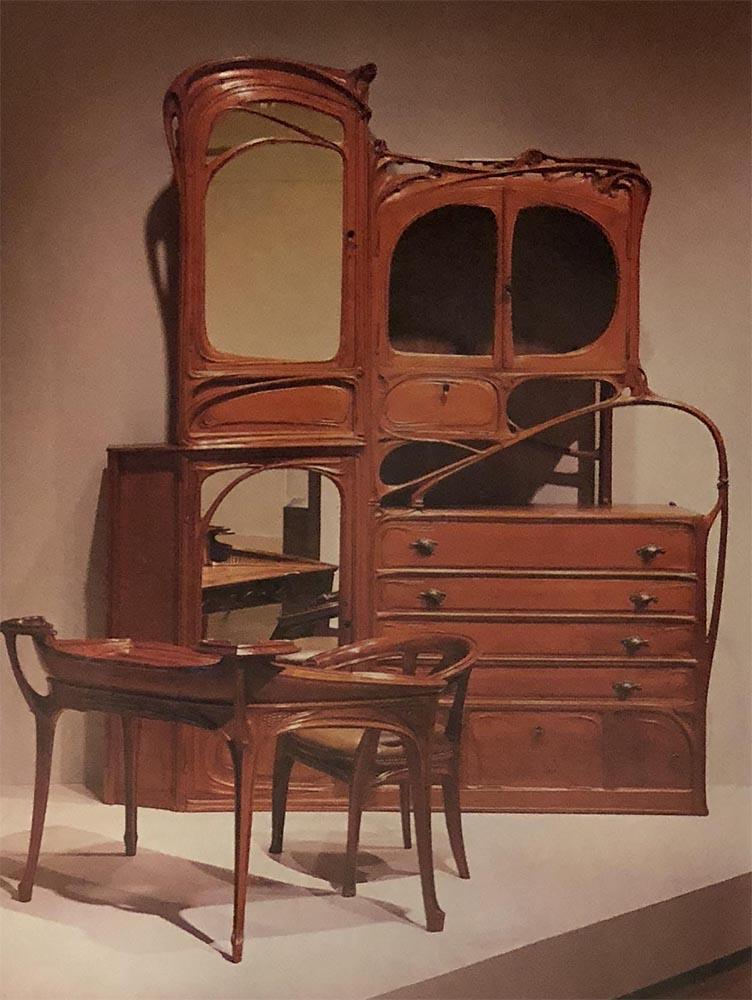

Art Nouveau triumphs by Hector Guimard, who did Paris Metro entrances.

A Dizzying Array of Giving

To the colorful history of Mom-and-Pop ventures, Sydney and Frances added an undreamed of dimension. Then, fueled by the generous proceeds, they began a dizzying array of giving: a $9 million gift to Washington and Lee University (Sydney’s alma mater) to build and endow a new law school center, Lewis Hall; $2 million to help establish Eastern Virginia Medical College near their summer home in Virginia Beach; a more “modest” outlay of $100,000 to the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts to buy the latest in contemporary art.

Their commitments to education and culture culminated in December 1985 with the opening of the $22 million, 90,000-square-foot West Wing of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. The Lewises not only pumped in $6 million but donated two fabulous collections of art, most of which, until then, had resided in their home. Their coequals in the creation of the wing, the Paul Mellons of Upperville, Virginia, matched the Lewises’ pledge and presented the museum with a select range of French Impressionist and British sporting paintings. The Commonwealth of Virginia committed $10 million to the building fund.

Although Sydney jokes that “I’ve given all my money away,” the Lewises remain peripatetic patrons of the arts. While Frances is active with the Virginia State Board of Education, Sydney commutes to New York and Washington where he serves as a board member of the Brooklyn Academy of Music and chairman of the trustees of the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden. Although they’ve retired from the auction circuit (for the most part), their quest for contemporary art and furniture takes them to galleries and studios in New York, California and Italy.

Sydney Lewis freely confesses that collecting is a disease, “although a pleasant one.” Since they began collecting, the prices of Art Nouveau and Art Deco objects have skyrocketed on the international auction circuit (one of Tiffany’s rare Cobweb table lamps from 1902 that sold at auction for $40,000 in the mid-1960s fetched $360,000 at Christie’s in 1980). The same goes for many artists represented in their vast contemporary collection. Their ingenious solution to high prices was to buy jukeboxes, beautiful vintage machines with exotic brand names like Rock-Ola. These jukeboxes line a long corridor at Best Products head. quarters, stocky sentries guarding the art treasures within. In typical Lewis fashion, 28 of their finest machines were exhibited in September 1985 at the Baltimore Museum of Art. The opening party sock hop, complete with a disc jockey spinning the familiar tunes.

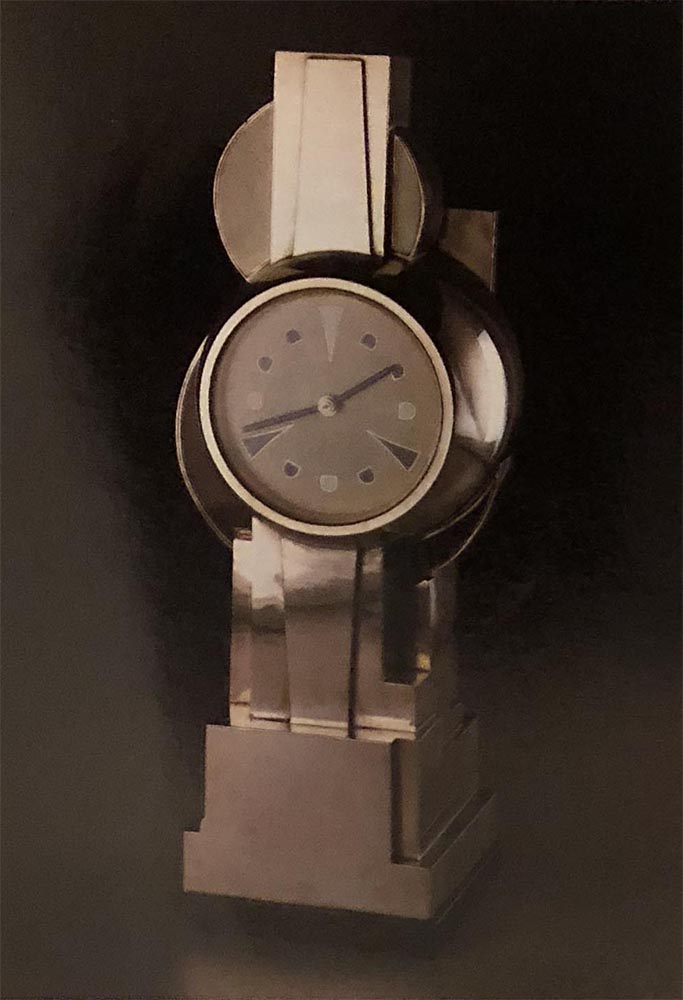

Jean Goulden 1929 clock is Cubist in format, sculptural in presence. He gave up medicine for design.

Back in the early 1960s when Best Products was first booming, the Lewises were scrambling to accommodate the explosive sales of brandname household goods at heftily discounted prices through a growing network of showrooms. The couple didn’t have a moment to appreciate art, let alone purchase it. Their frenetic pace continued until Sydney suffered a coronary attack in 1962 at the age of 42. “My doctor told me,” Sydney says, “I could die tomorrow, but if I decided to take care of myself, I could live to be 100. I decided to try for 100.”

That brush with death dramatically altered the couple’s lifestyle, and instead of cramming seven days’ work into four, the Lewises “spent seven days doing what should have taken four. They began to frequent art galleries and museums. Before that turnaround, Sydney could not recall ever seeing a contemporary painting. Even though he grew up in Richmond, he rarely visited the art museum. As he succinctly puts it, “I was a jock.”

“It was just three big blobs,” Frances Lewis remembers, sketching them vigorously in the air. She is describing their first purchase of contemporary art, a Jules Olitski abstract gouache, purchased at the Richard Gray Gallery in Chicago for $300 in 1964. “We walked out with it and I asked myself, ‘Did I just shoot the family fortune?’ ” They took it back to Richmond and had it reframed. If it had happened today or even 15 years ago, Frances would have had the artist made frame conserved and not just thrown out. But while the Olitski was at the framer’s she dreamed that he had cut off the bottom of the picture, including the signature. Unsettled by the dream, she called the framer the next morning and sure enough, Olitski’s signature, the benchmark of just about any work of art, had been lopped off. “So we wrote Olitski,” continues Frances, “and asked if he’d mind signing it again. We thought he would be upset.” Olitski accommodated the request and signed his name boldly in pencil across the front of the painting. That personal interaction between collector and artist was a harbinger of things to come.

Guardians of Taste Were Up in Arms

Today the Lewis home on Monument Avenue is just a block away from the imposing Jefferson Davis monument, “erected by the people of the South in honor of their great leader.” The columns of the memorial and the faded green statuary are an arresting counterpoint to the stately rows of landmark houses that line the tree-shaded avenue. It is no wonder that when the Lewises unveiled Claes Oldenburg’s totem-pole-size Clothes-Pin Ten Foot in their driveway in 1974, the local guardians of taste rose up in arms.

Oldenburg’s clothespin became almost as famous as President Davis’ statue. After the war cries died down, neighbors grew so fond of the familiar household object—blown up, Pop style, in Corten and stainless steel —that when it was temporarily removed to star in a sculpture show in New York, editors of the local papers pounded reporters’ desks for hard news of the disappearance. The sculpture was recently moved to its permanent home, just a half-mile away, standing tall on the outdoor sculpture terrace of the new West Wing.

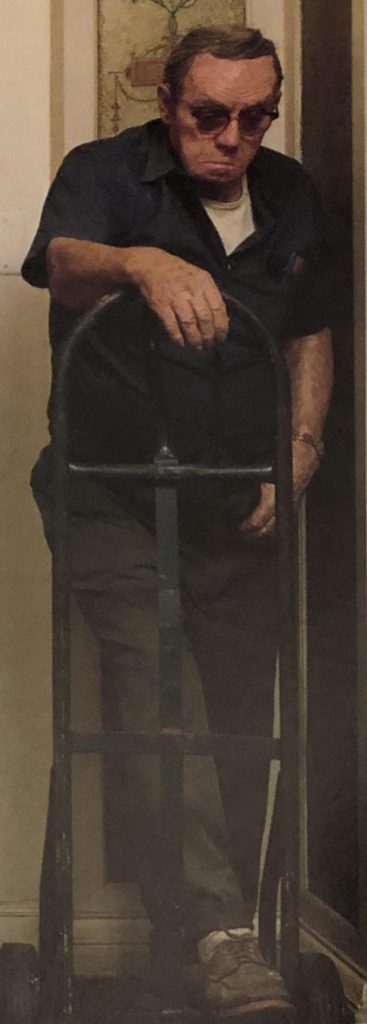

Duane Hanson’s lifelike blue collar worker.

The Lewis home, a sober brick mansion in neo-Georgian style, is full of surprises. A visitor is met by a sweaty man in work clothes, clearly disgruntled and leaning on a rubber-wheeled hand truck. Only later does one realize that the wrinkled worker is a life-size figure by sculptor Duane Hanson. be inside the house is to be surrounded by what the Lewises’ old friend, realist painter Jack Beal, calls “beautiful clutter.” Art and artist-designed furniture are scattered about—an absolutely label-defying array of fabrics, styles and images.

“They set things up so that each piece is in conflict but not chaotic conflict,” Beal says. “The juxtapositions rock you back on your heels but it’s good because it makes you look at objects more carefully.”

Those juxtapositions have, in large part, been broken at the new West Wing, where the Lewis Collection of late 20th-century paintings and sculpture has been segregated from the Art Nouveau, Art Deco, Tiffany and harder-to-categorize decorative arts like the Charles Rennie Mackintosh high-backed armchair or the Harvey Ellis fall-front desk. Malcolm Holzman, architect of the West Wing (and partner in the New York firm of Hardy, Holzman, Pfeiffer and Associates), said that his biggest challenge “was to avoid sterilizing this rich mix.” Thus there are many viewing points from the upstairs galleries—filled with decorative arts—that provide glimpses of the contemporary art in the galleries below.

Frances Lewis gets a “peculiar feeling” sometimes when she walks by some of the furniture installed in the marble-clad West Wing. We lived with those objects,” says Frances. “Now they’re up on pedestals, under spotlights with signs that say ‘Don’t touch.’

Although Sydney emphatically says “I’m a person who never looks back,” he still gets wistful on passing Willem de Kooning’s Lisbeth’s Painting in the West Wing, so called because the artist’s daughter had implanted her handprints in the wet oil. De Kooning left the prints there and at the same time found a name for the work. “They haven’t really left you, dear,” sympathizes Frances. “Once you have them, you have the pleasure in recalling how you found them, how you hung them.” Sydney reenters the conversational flow: “These really great experiences remain with you because it was the friendships with artists here and overseas that gave us so much pleasure.”

One such friendship was with the architect and designer Eileen Gray. She was 96 when the Lewises met her in Paris. “Did you come over on Twa?” asked Gray. It took a minute for Sydney to translate Twa to TWA. “No, Miss Gray, we came over on the wonderful Concorde.” Gray immediately launched into a detailed conversation on the merits of the supersonic plane and revealed to the Lewises that she had been an aviator in her younger years and had once passed through Houston to participate in an air race in Mexico back in 1956.

As Sydney says, “She was a fabulous lady.” He is particularly proud of their Gray holdings. His favorite is a fanciful floor lamp with a parchment shade from 1923, created for a bedroom-boudoir in Monte Carlo. The lamp, though, is pure sculpture, Cubist in design and handsome with sculptural tension. It stands at the prow of Gray’s Canoe sofa fashioned of lacquered wood and silver leaf The scope of the Lewises’ gift to the Virginia Museum is mind-boggling. Frederick R. Brandt, the Lewises’ onetime personal and corporate art curator and now the museum’s curator of 20th-century art, tried to convey the richness of the works. Pointing to a superb mantel clock from 1917, a gorgeous black cube with numerals inlaid in ivory by the Scottish designer-architect Charles Rennie Mackintosh, Brandt said, “Most museums would kill for one Mackintosh. We have seven.” Paul Perrot, French-born director of the museum, who assumed leadership during the West Wing construction, likens the museum atmosphere to “a bottle of champagne that’s just been uncorked.”

This is a view of the Lewises’ Richmond Bedroom before the furnishings we’re given to the museum. Extraordinary, fanciful furniture was the work of French Designer Louis Majorelle at the turn of the century.

Only a small fraction of their 1,200 contemporary paintings and sculptures can be exhibited at any one time. Many artists are represented in depth and the names read like a roster of blue-chip stars, from Pop artists like Roy Lichtenstein and Andy Warhol to Abstract Expressionists like Mark Rothko and Franz Kline. There are also huge holdings in what is generally called realist painting. (A major missing link is Jackson Pollock, whose works the Lewises regret never having acquired.)

A seminal moment in the Lewises’ collecting career came in the 1960s when they met Ivan Karp, who was then director of Leo Castelli’s uptown New York gallery—a showplace where reputations were made faster than art magazines could be published. Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein and Claes Oldenburg all showed there. Karp soon warmed to Sydney and Frances. “Sydney Lewis had an eclectic vision,” he says.

The Lewises began a simultaneous love affair with the art and artists of New York and the splendors of European design. They religiously read the Village Voice and attended all kinds of experimental music and dance performances at the Judson Memorial Church in Greenwich Village. Soon the Lewises and the artists set up a kind of casual bartering system, with artwork being traded for commodities from the evergrowing Best Products catalog. Trading art for useful objects, even for medical and dental services, was not unheard of in those days and more than one fine collection of contemporary art was begun or added to in various exchanges. For Sydney, it began when lie saw an ad in the Village Voice. It had been placed by Andy Warhol (in the days before his magnitude), who offered to exchange art for anything at all. At first he had wanted musical instruments and film, but he finally decided on a vacuum cleaner, among other things. In exchange, he would do a portrait of Frances.

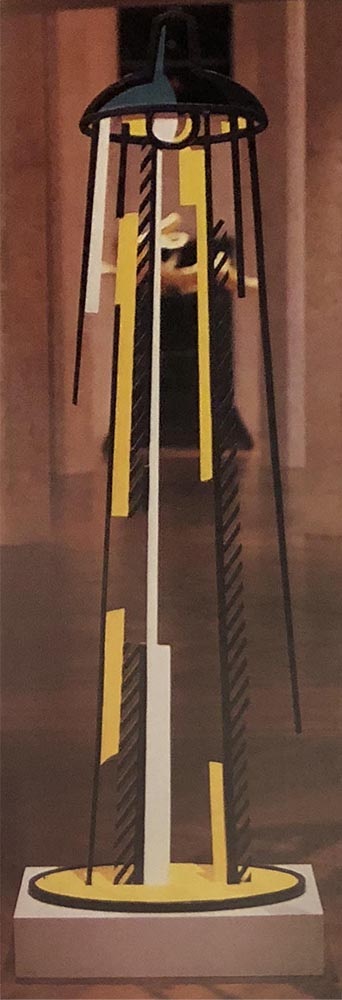

Roy Lichtenstein sculpture – Lamp II

Warhol met the Lewises in an amusement arcade on Broadway one afternoon and fed a stream of quarters, supplied by Sydney, into a picture machine that produced four-image strips. This process lasted about an hour and the result was hundreds of little photographs of Frances. One of them served as the model for a 12-section portrait. That first transaction was done on a personal basis. Sydney paid Best for the merchandise sent to Warhol. Later trades for the most part were on behalf of Best Products and the art obtained by them is still on display on various walls of Best headquarters and stores.

After the Warhol exchange, word went out in SoHo and, Sydney says, he was “assaulted with requests” for trades. Roy Lichtenstein asked for a refrigerator and other kitchen appliances. Jasper Johns prints were bartered for television sets, and Chuck Close, Jack Beal, Pat Stein and Robert Morris all ordered various household goods. As new appliances moved into grungy Manhattan lofts, paintings moved onto the walls of Best showrooms around the country.

With the continuing success of his company, Sydney Lewis found himself one of the wealthiest men in America; now it was time for philanthropy. In 1971, the Lewises made their $100,000 gift to the Virginia Museum and, of course, asked Ivan Karp to select the paintings. They established the Best Products Foundation under the direction of their daughter, Susan Lewis Butler. Active in the 28 states where Best stores are located, the foundation dispenses $1 million a year in support of the arts and higher education, with special emphasis on aid to teenagers.

Prodding the parties point-blank

Their approach to philanthropy was marked by characteristic Lewis style. They would call in the officers of a needy institution and ask them point-blank what they wanted. If the answers weren’t imaginative enough, the Lewises would prod the parties to come up with a grander idea. And so when Sydney Lewis said “Is that all?” to Washington and Lee’s request for a new law school building, the university officials thought it over and decided that a research-endowed law center would help too. (The Frances Lewis Law Center opened in 1979.)

The art collection was another matter. A number of topflight American museums lusted for the paintings and sculptures, but none of them had the capacity or the inclination to take on the decorative arts. The Virginia Museum couldn’t handle them either—it was already filled to the rafters and in desperate need of space. That’s when the idea of a new wing popped up and, between the Lewises and the Mellons, became a reality that doubled the museum’s gallery space. Last one in recognition of their art patronage, the White House honored the Lewises by awarding them the National Medal of Arts.

Best Products headquarters, just north of Richmond on Route I-95, is something of a museum in its own right. Also designed by Hardy, Holzman, Pfeiffer and Associates, the building is surrounded by a moat and sheathed with a wall of tinted glass brick. Two Art Deco limestone eagles that once graced the Airlines Terminal Building in Manhattan serve as splendid guardians to the main entrance. Inside, in Frances Lewis’s office, Sydney sits crosslegged, the picture of eclectic taste in a pink-striped shirt, black-and-white checkerboard tie and a muted cardigan resembling an abstract painting. Frances sits behind a blood-red lacquer desk designed by the Italian architect Gaetano Pesce- the kind of piece that is sometimes called “interactive sculpture.” Behind the desk, incredibly, is a Cabbage Patch Doll with a birth certificate for one Sid Lewis—sent, Frances explains, by a worker from the warehouse.

Sydney speaks now of their gift to the museum. “We wanted to enjoy giving it away and not have our children have all the joy of doing it. We both sort of came to the idea at the same time. I really wanted to be part of the final disposition of these objects. But I couldn’t do it if I were dead. That’s what started me thinking.”

“You made the decision in two minutes,” Frances chimes in. “You just woke up one morning and decid-ed. Just like you did when you decided to start Best.”

“I was getting ready to say that,” says Sydney.

Later, driving his temperamental sports car down to visit the museum, Sydney Lewis talks about his mother, Dora, who worked for Best practically from its creation in 1957 to just months before she died in 1984. Dora was a workaholic and always brought papers home in two big briefcases. Since she always worked in “accounts payable” and all she ever saw at Best were the bills, Dora warned Sydney weekly of the disasters facing the company. “She was from the old school,” he says. “She’d spend $5,000 to locate a recent mistake. You had to do things right, regardless.”

Sydney navigates his electric-blue coupe (with the initials of his alma mater, W&L, on the license plates) into the driveway of the museum and, with the engine still running, unscrews his tall frame from the low-slung bucket seat. There is a young museum guard standing near the entrance. He notices the car and driver and asks his senior colleague who the fellow is. “Why, that’s Sydney Lewis,” huffs the elder guard, “he owns the place.”

Sydney spies a group of young visitors and makes a beeline for them. He asks a wide-eyed youngster if he has enjoyed his visit, and after the boy’s tentative nod, urges him to come back again.

One cannot help thinking that Sydney Lewis must have paid attention to his mother’s words about doing things right regardless.