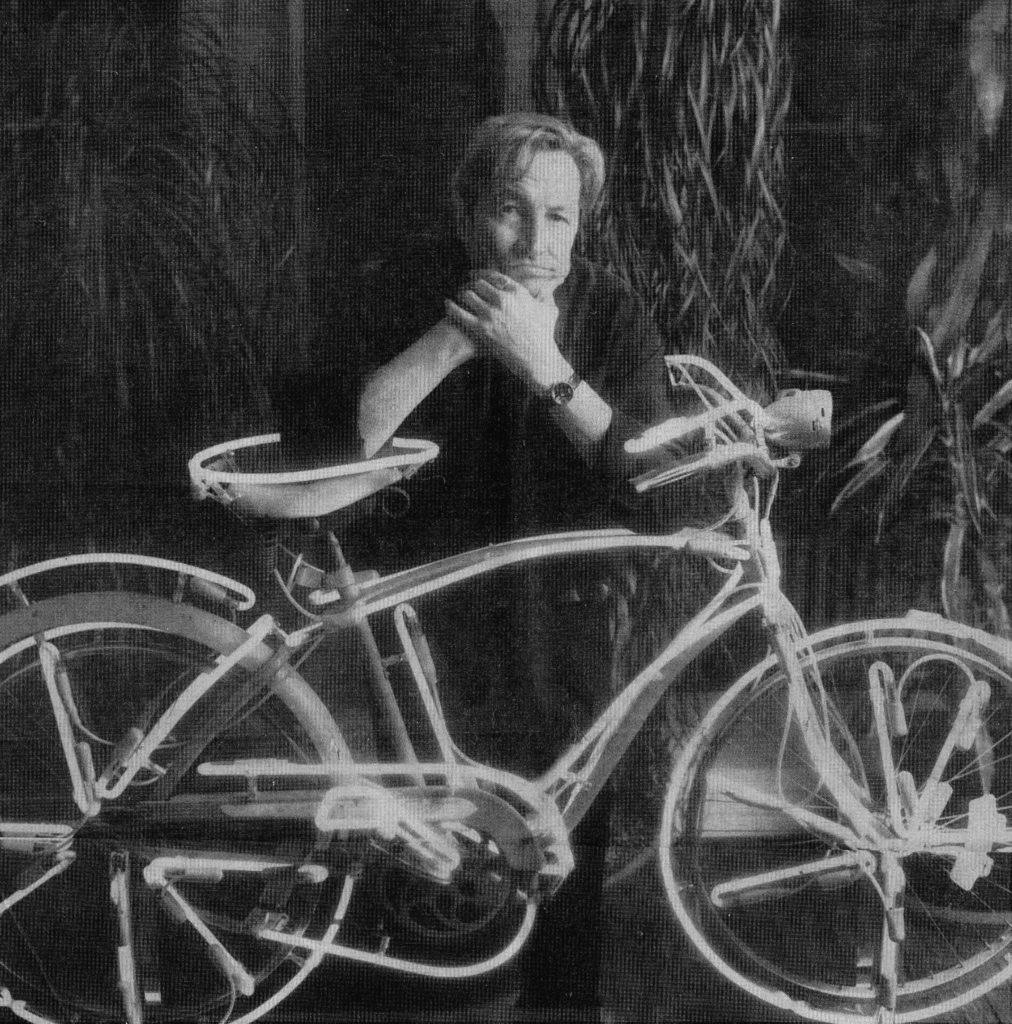

Robert Rauschenberg in his Lafayette Street studio — his newest work pushes production and content still further together

Rauschenberg’s alchemic wizardry transforms you-name-it detritus into barely elegant sculptural “gluts” and shakes up Knoedler’s pristine space. Night Dock Sled Glut is comprised of a chlorine-eaten swimming pool ladder, yanked from somewhere and rein- vented as a kind of ’90s Rosebud. Clamped to the pock-marked runners are a trio of old and awful green tracklights ready to illuminate a distressed landscape. The” Gluts” rudely intersperse w ith the artist’s wall-mounted Night Shades, his ongoing narrative series of photo silkscreens on various metals. This chapter, it’s aluminum, broom-brushed with sulphur-laced tarnishes that distress the surfaces as efficiently as a toxic waste dump.

Dog-On (Night Shade) is (in part) a ferocious image of a big-chested boxer, poised to spring from its aluminum territory and sink exposed teeth into the viewer’s flesh (so pass by carefully). Visible in the smudged layers and grey- black mists are image shards of urban architecture and foraging dogs, lean and hungry.

A few days before the opening at Knoedler, I asked Rauschenberg about his Night Shades series during an impromptu interview at the kitchen table of his NOHO loft building, a former orphanage. Rauschenberg had just come in from Washington where he’d received a Presidential Design Achievement Award for his National Gallery of Art exhibition design, “Rauschenberg Overseas Cultural Interchange (ROCI) 1984-1994,” the artist’s globe-trotting five-year ventures.

“It comes from an interesting group of herbs, such as foxglove,” noted the artist as he lit a cigarette. That led to a discussion of Van Gogh’s famous Portrait of Dr Gachet, with the smiling homeopathic physician seated in front of a sprig of flowering foxglove, the source of digitalis, a cardiac stimulant.

Dr. Gachet’s remedy didn’t save Van Gogh, but the revelation of Rauschenberg’s research into that plant family brought the swirling and tarnished surfaces of the Night Shade paintings into sharper focus. The mysterious gunk that coats their metal skin also veils the photographic montages that float to the surface. Their poisonous yet beautiful attributes mime nature’s own deadly nightshade.

“Once again, I’m trying to force people—that’s about as aggressive as I get with art—to have to be there when they see something. That’s not too much to ask.” (The approach works like a charm, and the menacing image of the jut jawed boxer snarls back into view.)

Outfitted casually in a dark blue shirt and pants, a gold ring on his left index finger, Rauschenberg looked surprisingly young for his 66 years.

“I’ve been working in metals for a long time. It sort of started in Chile when Pinochet was in power. Copper was their greatest export. I became fascinated… Early on, I used mirrors to pull the outside world back into the interior of the paintings. So the concept isn’t new. It’s just how much I exaggerate.”

“Robert Rauschenberg: The Early 1950s,”curated by Walter Hopps, opens at Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Art this week, coming on the heels of a Whitney Museum of American Art traveling show of his silkscreen paintings from 1962-64. There have been other museum extravaganzas in Paris, Madrid and Barcelona. “If they start slicing me any thinner in time, they’ll need some cantaloupe to wrap some Rauschenberg prosciutto around to get a taste of the meat,” retorted the artist after hearing the laundry list.

Pressed for a response to Hopps’ claim that he’s “one of the U.S.’s most influential 20th-century artists,” Rauschenberg deflected the accolade: “If you’re working badly, no amount of praise or rhetoric will make you any more talented. I’d rather celebrate my impatience ad curiosity which leads me into all kinds of materials that have not been necessarily seen together, to celebrate that I still have an innocent curiosity about how things go.” Alluding to the established icon of oil painting, he said, “All I’m trying to do is get everybody off the highway, and if anybody follows my lead, they’ll soon be lost too.”

Anticipating another question, Rauschenberg asked in mock surprise—”Is this an inquisition? If it is, I’m guilty. It’s all deliberate. I’m prolific, see, I hope that’s not a dirty word yet.” Joking with a kind of cackling laughter, Rauschenberg noted that he began giving his old signed brushes to charities for auction benefits “because I think they like my old paint brushes better than my new paintings.” The artist’s “respect for chaos” has not always put him in good stead with dealers or collectors, though Rebus, his 1955 combine painting, sold for a whopping $7.26 ‘million at Sotheby’s last April. When Rebus first hit the auction block in 1988, Rauschenberg unsuccessfully tried to convince the owner and auction house to earmark 1% of the proceeds to Change, his foundation that helps destitute artists. “These people don’t realize that if you don’t support the artists you don’t have art, so how can they get rich?”

Asked about the dealers he’s associated with over the decades—from his first solo with Betty Parsons in 1951, to Leo Castelli, Ileana Sonnabend and on to his current affiliation—he said, “I don’t have dealers that I don’t want to have dinner with.” That was followed by a question on the veracity of an old art world legend that Leo Castelli came to Rauschenberg’s Fulton Street studio in the ’50s but swooned over the work of Rauschenberg’s pal, Jasper Johns and gave him a show first. Rauschenberg laughed and said, “Jasper got the show and I didn’t. It’s as simple as that. Leo came over for dinner. I did a wild duck on a hot plate.”