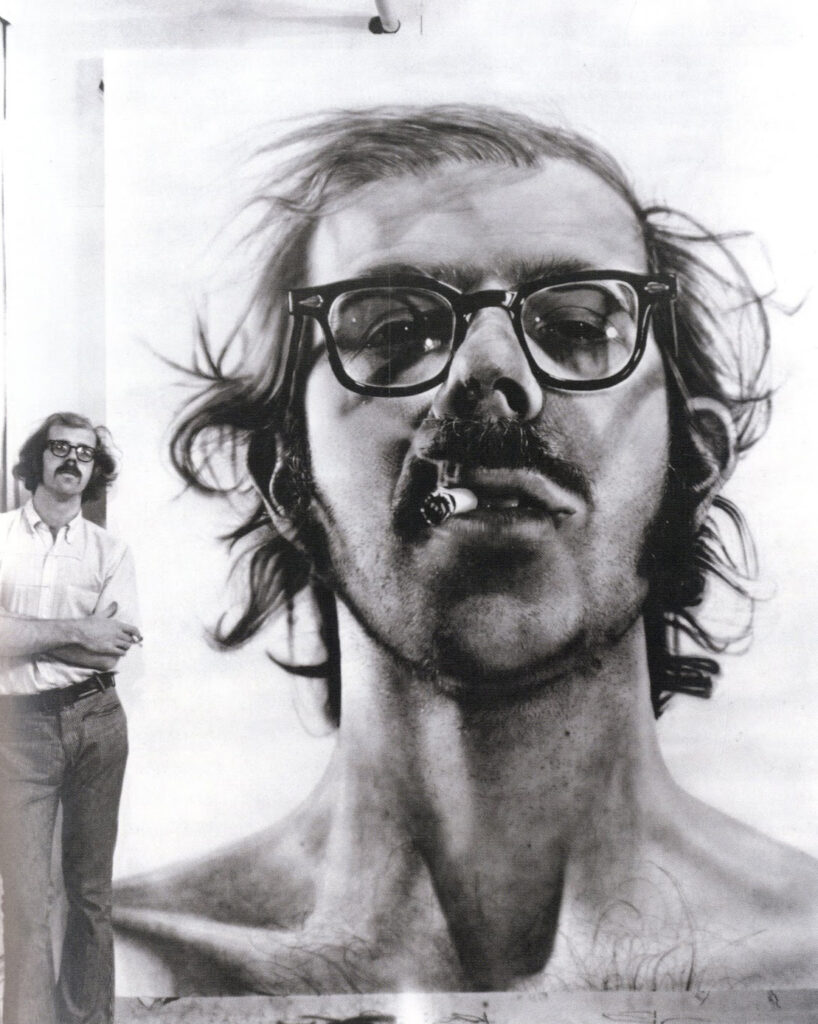

Chuck Close standing next to self-portrait, 1968

I conducted a series of long-play cassette taped interviews with Chuck Close back in the spring of 1987 for the Archives of American Art, about 18 months before his catastrophic spinal artery collapse that paralyzed him.

One of the big takeaways for me from those interviews was the artist’s childhood in Washington State and struggles with severe dyslexia, a condition that wasn’t even clinically diagnosed at that time.

Chuck described the exercises he invented as a child, with a candle and a book propped up while he sat in the bath, trying to train his mind to unscramble the letters. Ironically, the condition enabled him in later years to become a world-class print maker.

Sitting for hours in his NoHo studio, listening to his captivating stories about how he became an artist and the impact on his life when he saw his first Jackson Pollock, and all the while, stationed close up to his work in progress, large-scale canvases and the various tools he used to make them, was a stellar experience.

Decades later, whenever I saw Chuck at an opening, say at the Cindy Sherman retrospective at MoMA, dressed up in a camouflage patterned outfit & seated in his custom wheelchair that could be elevated to meet a standing person’s gaze, he would always be genuinely friendly and curious about what I was recently up to.

Later scandal aside, Chuck Close remains an important and certainly lasting figure in Post-War American art.

The following is from Oral history interview with Chuck Close, 1987 May 14-September 30. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

JUDD TULLY: According to published information, you were born in the state of Washington in 1940. What was your actual birthdate and tell me a little bit about Monroe, Washington?

CHUCK CLOSE: July 5, 1940. Monroe, Washington, was a smelly little town halfway up the Cascade Mountains, northeast of Seattle. I didn’t live there very long, actually. I was born at home — not in a hospital — of humble beginnings. Actually, I want to go back and photograph the house, because if I were a politician it would be great to have a picture of the shack that I was born in. [They laugh.]

MR. TULLY: Was it really a shack?

MR. CLOSE: Well, it wasn’t a real shack, but it was a very modest little cottage. “Cottage” is giving it all the benefit of the doubt. It was definitely on the wrong side of the tracks — about thirty five feet from the tracks. My father at the time was a sheet metal man and was also working in a hardware store. He was sort of an itinerant inventor, a jack of all trades. Probably basically unemployable. He had a lot of skills and seemed to — coming out of the Depression — had just had a whole string of handyman kind of jobs. My mother was a trained pianist, but the Depression pretty much screwed up her chances of any kind of a career, although she did teach piano at home.

MR. TULLY: So what were their names?

MR. CLOSE: My father was Leslie Durward Close and my mother was Mildred Wagner Close.

MR. TULLY: About how old were your parents when you were born?

MR. CLOSE: My father was born in 1903 so in 1940 he would have been 37. My mother was 10 years younger so she was 27. I was an only child. I recently found out that my father had been previously married and had another child, but I didn’t find that out until I was 40 years old.

MR. TULLY: How did that come up?

MR. CLOSE: I got a call on the phone. My mother never told me. Even on her deathbed she never told me.

MR. TULLY: She obviously knew?

MR. CLOSE: Yes. It’s strange. I guess there was tremendous embarrassment about all that stuff. My aunt claims that my father didn’t really think the child was his, and married her because it was a small town and somebody had to or something like that. But I don’t know. I’ve since met the man. He says he’s my half brother and I assume he is. But I was raised my whole life as an only child and my mother was an only child and my father was virtually an only child. He had a half brother who was much older. So it’s like a lot of solitary souls.

MR. TULLY: And you said you weren’t there very long in Monroe?

MR. CLOSE: No. I think when I was just a year or so old we moved to Everett, Washington, which is an even smellier town. It’s on the bay. It’s a poor, whitetrash mill town. It is the smelliest city in the world, I think. It was all paper mills with that process where they break down the wood and it produces an incredible smell. I lived there until I was in the first grade and we moved to Carmel. My father started working for the Army Air Corps. First he worked in the air force base in Everett, and then was transferred to one in Tacoma, so we moved there. I stayed there until he died when I was 11.

MR. TULLY: So he died very young.

MR. CLOSE: He was 47 when he died — almost 48. My mother and I moved back to Everett. My grandparents were living in the house that I had grown up in and then we bought the house next door to them, so my grandparents could help take care of me. My mother who had never worked — other than teach piano — had to go to work.

MR. TULLY: So by that time when you moved back you were —

MR. CLOSE: I guess I was 12 when we moved back.

MR. TULLY: I meant to ask you before — you were Charles?

MR. CLOSE: Yes. There were only a few names in my family. People were not too inventive. Everybody was Charles Thomas or Thomas Charles or whatever — my grandfather was Charles — so all the names were taken. I was little Charlie. There was Big Charlie and Little Charlie. To my relatives I’m always still Charles, although I have only one relative left. I guess it was some attempt at individuation that in high school I started to go by Chuck. I always hated the name. But it’s a total accident that Chuck is my professional name. I didn’t intend that to happen which, skipping ahead, but it’s anecdotal. Everybody knew me as Chuck, but I had intended to use Charles as a more formal name. Very early in my career Cindy Nemser did an interview which was used in ArtForum. Actually she did two. She did an article for Art in America which says, “Introducing Charles Close,” she titled that. Then in the interview she didn’t title it and it just said “Chuck Close” and “CM.” The photographer, who was a student of mine, took the photographs for ArtForum and he’d just written “Chuck Close” on the envelope, so it went down as an interview with Chuck Close. I don’t know if a similar thing happened with Red Grooms or not, but the whole kind of informality of it was not — I regret it. Hardly a day goes by that I don’t regret having that as my professional name.

MR. TULLY: When did this ArtForum piece and Art in America piece come out?

MR. CLOSE: That must have been about 1968 or 1969, I guess.

MR. TULLY: So when you said one of your students you were teaching–

MR. CLOSE: I was teaching at the School of Visual Arts.

MR. TULLY: Okay.

MR. CLOSE: Now do you want to go back to the early years?

MR. TULLY: Yes. You had moved back to Everett. You were living at home with your mother and she was working and your grandparents were next door. What was the school atmosphere like? What was going on around then?

MR. CLOSE: Now I realize — or I found out later in life–that I am dyslexic. In the ’40s and ’50s of course nobody knew from or gave a shit about something like that, so I had a lot of difficulty in school. I don’t have a typical kind of learning disability. Although I did just find a drawing that I made when I must have been about three or four — I was already writing, so I was probably around four — in which I wrote my name all in mirror writing so probably there were indications that now somebody would see immediately as an indication of something, but at the time it didn’t. I still can write mirror writing as fast as I can write forward. I can write backwards and upside down as fast as I can write forward.

MR. TULLY: That sounds quite something. And then you can read it also as easily?

MR. CLOSE: Yes. And, also, making prints was very easy for me. I immediately have no trouble imaging what something looks like the other way. I did a self-portrait etching a while ago in which it was reversed — of course — and it was a negative because the bright copper plate had a dark ground. As I was sketching the lines they were going to be black and I was white, so in a sense I made the equivalent of a photographic negative reversed and negative. Everyone seemed to think that was kind of amazing that I could do it and it seemed not at all a difficult problem to me. [Laughs.] But at any rate, one of the characteristics of the kind of learning disability I have is a problem with facial recognition. Everyone I’ve ever seen or people I look at all look immediately familiar to me, but I have tremendous difficulty figuring out who it is and where I’ve seen them before. I never can memorize. To memorize something was unbelievably complicated and I developed my own systems to be able to remember which are now are very similar to the kinds of things that they try to teach learning-disabled children. It’s something I evolved on my own, which I guess is probably the basis for–I’m sure I’m not the only person to have evolved systems like this. These systems have probably become the basis for how to teach other people.

MR. TULLY: Like what though? What did you do to prompt you? What is an example?

MR. CLOSE: There was no sense in trying to memorize anything very far in advance because I could only — I used sensory deprivation. I would go into the bathroom where I would — in the dark — put a strong light on a plank that I had across the bathtub with a book stand to hold the book and in hot water — in total silence in the dark — I would go over, and over, and over whatever it was I was supposed to be memorizing all night long before an exam. Just the very last minute that I possible could go over the stuff. I was a virtual prune I was so wrinkled from studying. But it was like I had to get rid of all the other distractions and everything else that was going on in order to focus and concentrate and stare at these things. Then in order to remember it I would take a word and I would break it down into letters. Then I would make a sentence. If I had to remember the name of a biological species or something like that– say the word was — I don’t know what it would be–now, of course, I can’t think of anything. [Laughs.] But if it were “plankton” or something like that, then I would put “please leave” da, da, da, and I would have a sentence. Then I would have a visual image of that sentence or it would be pink, long, or something that would be visual. So then when I’d need to recall this I would get the mental image, the mental image would feed me the sentence, then I would extract from the sentence the appropriate letters and rebuild the word. This worked reasonably well, but it of course ate up a lot of time. So typically on my exams if there were 20 questions, I would have the first 15 questions correct and then of course the last five I didn’t have time to do. Now if you are a learning disabled person you can choose to take exams in an untimed way. For instance, you can take SATs and things untimed for people who have this kind of a problem.

MR. TULLY: When you are giving this example of that board in the bathroom–when did that start?

MR. CLOSE: I remember it around that time that exams started. I guess probably in junior high school. What I really would like to explain is how art really saved my life because art is how I proved that I wasn’t a malingerer and how I proved that I was interested in the course material. Even in grade school, when I had trouble memorizing names and dates and anything that would be an indication that I had paid attention in class or read the material I had trouble recalling it and I was immediately seen as a malingerer. Art was the thing that I used. I remember making a 10-foot-long map of the Lewis and Clark expedition, all illustrated–as an extra credit project–it showed my junior high school history teacher that I was interested in the material. And if I had a sympathetic teacher, that would make up for other things. English class I would make poetry books in which every poem was illustrated, et cetera. So I think early on my art ability was something that separated me from everybody else. It was an area in which I felt competent and it was something that I could fall back on. Similarly, I also have a neurological condition which does not allow me to run or to use my arms in certain ways. So not only was I a screwed up student, but I wasn’t able to excel in sports or even to just participate. So as a kid when we were playing tag and everybody would run, they would run off and leave me. I’d run 25 or 30 feet and my legs would lock up and I would fall down.

So I think I learned early on that if I was going to have friendships — and as an only child I had no built-in playmates — that I was going to have to find a reason to get them to stay with me because I was not going to be able to keep up with them. So I got into what I would call sort of entertaining the troops and I became very theatrical. I’d make puppets. I’d do magic acts. I did everything that I could do and I became very skilled at organization. I would convince the other children that what we should be doing was something that I could do. Art was definitely –or things that might be considered artistic or something about manipulation of materials in some way — became–and my parents were also very sympathetic and also helped in that. They helped me make puppet stages and helped me make magic. My father, as an inventor, would make all kinds of magic props, as he made almost all my toys from scratch. So I definitely had an unusual childhood.

MR. TULLY: You were mentioning your father. So you would be around him when he would be working?

MR. CLOSE: Yes. My father was very sickly — had been sick his whole life. My mother was told several times before he actually died that he was going to die of something else, so there was a lot of role reversal stuff, which was for the ’40s very unusual. My mother mowed the lawn and my father would bake. I remember my mother overhauling the car — putting in rings and valves, et cetera. My father would tell her how to do it and she would. He was very skilled at that sort of thing, but he was unable to do a lot of it. She would keep running into the house and say, “What’s this?” And he’d say, “You’ve got to do–” And she’d go back out and do it. So he was around a lot. He was home a lot, which most fathers weren’t.

MR. TULLY: I just think of this image when you said this “10 foot-long map of Lewis and Clark.” So in other words you blew up —

MR. CLOSE: Oh, yes. Somehow, visual stuff — It’s like nature or God or whoever if you believe in God. It’s a convenient metaphor. It seems almost like if they take something away from you over here they give you something else over there. Or nature does. I am more comfortable with that. But at any rate, certain skills seem to have come easily for me and of course the more I depended on them, probably the more I developed them. But I knew at a very early age how to read things. I remember it must have been somewhere between the first and third grades I lived in a housing project and everybody in the school lived in the same housing project. We made a map of the housing project in which everybody made a drawing of their own house and colored it the color their house was, et cetera. I made a drawing of our house in perspective. The teacher wanted it to be like wrong. She didn’t know how to draw in perspective, so she kept telling me that mine was wrong and wanted me to make the ends of the house straight instead of sloped to be in perspective. I had the sense of outrage even as a very small child. I couldn’t have been more than seven or eight. The fact that here is something which is unbelievably clear and that I knew that I could do it and I knew that I was right and that somebody else who did not understand the system could force me to do it the wrong way.

MR. TULLY: So what happened then? Were you rebellious in a sense or resistant to–

MR. CLOSE: I couldn’t be too rebellious, because they already thought — mostly, I was trying not to draw too much attention to myself. Although I always was articulate, I think. And I think that I made up by participating a lot in class. My daughter is also dyslexic and she’s been that way. When somebody asks a question, she’s the first one to raise her hand and to show that you care — that you’re interested. As soon as I got into college, I could do a little research into what each instructor would require and try never to take a course that would require me to do something that I wasn’t good at. So I’d find things where I could write a paper. Of course I can’t spell or do anything like that, but I could take it to a typist who could. So I could — in my own way, at my own speed –write a research paper, have the spelling and stuff corrected and I was an excellent student –finally. In junior high school I had an 8th grade homeroom teacher who was a stickler for doing it by the book. If I could get this woman in an alley, I would murder her today. I had her for English, history, math. I had her for, like, four of the subjects. I had always managed to do pretty well. Oh, I had nephritis and I was in bed for nine months so I missed most of a year of school. It was the year my father died.

MR. TULLY: What’s nephritis?

MR. CLOSE: It’s a kidney disease. So I missed a year of school. My father died and we moved to Everett. My seventh grade was fine. Coming out of the disease, I couldn’t do a lot. I stayed in the classroom. I couldn’t go to gym or anything. I had a very good relationship with my seventh grade teacher and she was pleased with my work and I got good grades. Then in the eighth grade I had this stickler for doing it by the book.

MR. TULLY: Do you remember her name?

MR. CLOSE: Ruth Packard. I would love to get my hands on her throat. At any rate, she gave me like straight Ds. She couldn’t fail me because I did enough extra credit stuff to keep from failing, but I never could please her. She became my advisor for high school, and she so totally trashed me, and through the course of the year of failing me on this and failing me on that, I was just destroyed. She told me that I would never get into any college and I might as well not take any college preparatory courses. I should think about going to body and fender school or something, and that I wouldn’t be able to take algebra and geometry, and I wouldn’t be able to take physics and chemistry, so I’d better take general math and general science and whatever, which is what I did. Then when I was getting out of high school, I realized that I could not get into any college because I didn’t have the stuff. After I had gotten out of her class I had done very well and good decent grades, but I was taking basically bonehead kinds of courses and I was in there with all the troubled kids. But I always did the yearbook and the art and all that kind of stuff. I had things which made me feel good about myself, art always made me feel good about myself. When I did graduate from high school, luckily, in my hometown there was a junior college that had to take any taxpayer’s child who was a high school graduate. They could not not take them. So I got in to this college and made up all the — I had to make up an extra 15 hours in the way of science — algebra and geometry– for no credit. But at least I was able to do it and I distinguished myself in college very quickly. I was an excellent student. I ended up with the highest average when I transferred to the University of Washington. But I still had this image of myself as a failure and as not an academic. As I graduated, I was shocked to find that I had the highest grade point average of anyone in the art school and they gave me an award. I graduated summi cum laude and all that stuff without realizing it.

MR. TULLY: You were still driven by this Mrs. Packard?

MR. CLOSE: That’s right. To make an analogy, I was very late in maturing. I was very short. I’m now 6’3″, but then I was — I kept growing in college. My mental image of myself is still as a short person, because all through the formative years I was the shortest of all my friends. So even though I know I’m tall I think of myself as short. In the same way that while I distinguished myself academically, it was like I ignored it all and still had an image of myself as being a failure as an academic.

MR. TULLY: When all this stuff was going on — I was just trying to think about that — you were on the one hand being persecuted in a way by this teacher, but you were getting some positive things from your mother?

MR. CLOSE: Oh, yes. Actually, I left out that when I was about eight my parents enrolled me in a private art class with a person that I later figured out probably supported herself as a prostitute. So it was sort of an art class in a brothel, which is kind of amazing, too.

MR. TULLY: It sounds exciting.

MR. CLOSE: Yes. But the nude models were probably other women of the night. At any rate, I was at age eight or nine studying drawing from live models and painting with professional oil paints and all that stuff. Again it was something that I had tremendous support in from my family. Thank God they were not particularly concerned with me being successful at things I couldn’t be successful at like sports. They were very supportive. Considering the kind of poor whitetrash environment in which we lived and the very humble things — we were always lower, lower middle class I guess — it was unusual, I think, for them as parents to be supportive of that sort of thing. They were always very supportive of me. My mother was very active. Too much so. She was always head of the Parent Teachers Association. She was always there at school fighting for me, which was an embarrassment. I felt wimpish sometimes, because my mother was there taking on the administration. But I’m sure she made it possible for me to be as successful as I was. She was a little too involved. In Cub Scouts she was a den mother. Whatever it was, she was always there.

MR. TULLY: Was it your mother who found this private art–we’re not talking about Everett?

MR. CLOSE: No, this is Tacoma. My father stopped at a restaurant on the way to work and it was across the street from where this woman lived. She was a trained painter. She was very skilled.

MR. TULLY: What was her name?

MR. CLOSE: I don’t remember. He had breakfast there every morning. He may have very well done more than have breakfast. [They laugh.] At any rate, he knew her. How her knew her I don’t know. Somehow she had paintings hanging in this restaurant or whatever and he made arrangements for her to teach me privately. I have some of the paintings that I did.

MR. TULLY: That would be great. So you went there would it be after school or on the weekends?

MR. CLOSE: I don’t remember what it was. I suppose it must have been on weekends. I know I went every week. I’ve lost all the drawing notebooks and things that I did then. She had me doing very interesting stuff. It was academic. It was how many heads high people were, et cetera, but she taught me a lot about the conventions — perspective and all that sort of stuff. Also I painted directly in the landscape. We would go out and set up an easel in front of a church or something and we would paint it — or in the mountains. Also I guess we probably also worked with photographs come to think of it. Still lifes and stuff and from models.

MR. TULLY: And it was just you?

MR. CLOSE: Yes.

MR. TULLY: That is amazing. Your parents — was it a sacrifice for them?

MR. CLOSE: I suppose it was. But you know the thing is that my father was not — if I’d wanted to go out in the front yard and throw the ball around they would have done that, and I didn’t want to do that. They always got me lots of art materials and all I did was draw. I think because my mother was a pianist and my father was interested in — they had both followed very quirky routes to where they were.

MR. TULLY: Did you pick up anything from the piano?

MR. CLOSE: I couldn’t let my mother teach me anything. That was a big problem. I think I learned one piece which I can still play and that’s that. Then I wanted to do something she couldn’t do, so I started studying the saxophone. I played a sax all the way through college in dance bands and stuff. I was always first chair. It was another area in which I excelled and made up for the fact that I was having so much trouble in other areas.

MR. TULLY: So it doesn’t sound to me like you spent a lot of time say at home watching television.

MR. CLOSE: We had no television. No one in my neighborhood had one until I was probably — I think the first television that showed up in our area was 1951 or so so I would have been 11. But I didn’t have a television until I went to college. My grandparents had a television.

MR. TULLY: But I mean it sounds like you were working all the time. Not working, but you were —

MR. CLOSE: Radio was very good. Radio fantasy stuff was very good and I can still tell you the exact order of shows as they came on the radio. Especially the year that I spent in bed, I listened to all the radio soap operas too. “Young Dr. Malone” and “Helen Trent” and all of those radio soaps — “One Man’s Family” and all that stuff. And then of course all the evening ones. “Sergeant Preston of the Yukon”, and “Inner Sanctum”, and “FBI”, and “Kings of War”, and all those. I was really into them. And I drew. I had the professional 80-color Mongol colored pencil set, that I loved.

MR. TULLY: And this again was something that you had picked up in terms of mixing colors, learning how to do it?

MR. CLOSE: Yes. I don’t know. I think I had that stuff very early. But I remember the Sears Roebuck catalogue. Everybody looked through the Sears Roebuck catalogue. The first thing that I can ever remember asking for out of the catalogue was a professional oil paint set that they sold. Not only that, I can still smell those paints. In fact, I opened a tube of paint recently that had the same smell that that Sears Roebuck paint had. I guess maybe it was cheap oil. God! A sort of waft of this smell hit me and it was the smell of my childhood. But I had also very elaborate puppet show things where we made our own puppets and staging and backgrounds. My father helped me. I had a model railroad thing — first a Lionel and then HO — in which I made all the mountains. My mother sewed costumes. I did a lot of theatre stuff. I had a top hat and tails that they got at the Salvation Army for my magic act. So they were very supportive of anything that I wanted to do that — a lot of it was the kind of fantasy play– all the children get into.

MR. TULLY: So mixed in with this was there occasion for you to go to a museum?

MR. CLOSE: We would go to the Tacoma Museum, which was pretty much a historical museum. I remember I loved the Saturday Evening Post covers and I really was very interested in illustration. I don’t think I discriminated that much between — there was a lot of illustration that was painting at the time. Whether it was Boy’s Life covers or Saturday Evening Post covers. I remember the Jack the Dripper issue of Life.

MR. TULLY: Jack the Dripper is Pollock?

MR. CLOSE: It was on the New York School and what an outrage it was. I remember that very well. I remember at age–my father was dead so I was probably 13 –when I saw my first Jackson Pollock in the Seattle Art Museum. At first, I was outraged by it. It didn’t look like anything. It totally eluded whatever I thought what painting would look like. I remember feeling outraged, but later — probably even later the same day — I was dribbling paint all over my canvas.

MR. TULLY: You went on a trip to Seattle?

MR. CLOSE: Yes and I think we were already living in Everett. My mother took me to the Seattle Art Museum.

MR. TULLY: So Everett’s close to Seattle?

MR. CLOSE: 30 or 40 miles.

MR. TULLY: Yes, you said that. So I wonder if that Pollock–for instance–

MR. CLOSE: They didn’t buy it, I found out later. It was one that was lent them and they could have bought it and they didn’t.

MR. TULLY: I was just wondering, because there was just a show at the Guggenhiem from Peggy Guggenheim paintings that she dumped on all these regional museums where she couldn’t sell them from Art of This Century [Gallery, New York].

MR. CLOSE: This would have been probably 1952 or 1953. I don’t know what piece it was, although I think it was offered to them for sale and they didn’t buy it. I saw all the local Seattle people who were of the Northwest — [Morris] Graves, [Mark] Tobey. There was lots of that stuff around, most of which I didn’t like. I liked Mark Tobey’s white writing, but I didn’t like it.

MR. TULLY: At that time?

MR. CLOSE: I think by the time I was in high school. Like I say, I came home and dribbled Jackson Pollocks when I was 12 or 13.

MR. TULLY: So the idea formed then about being an artist?

MR. CLOSE: Always wanted to be an artist since I was four. Always wanted to be an artist. Now around high school, I also got interested in things like sportscars and stuff like that, so I thought I’d better be a commercial artist. Practicality reared its ugly head. All the way through high school I was doing the yearbook and all the other stuff. When somebody would run for senior class president or whatever I always did the posters and so forth. So I was already interested in doing things that had a purpose and I liked illustration. MAD magazine had come out. I have all the early MAD magazines from when it came out, I think in 1957. So I wanted to be like a cartoonist — an illustrator. Actually what I really wanted to do was Time magazine covers. Later in life I’ve been asked to do Time magazine covers and I just don’t want to do them. But at the time that’s what I saw as a sort of pinnacle of painting. So when I actually entered college I wanted to be a commercial artist, but you have the same foundation courses for painting as for commercial art.

[End Tape 1, Side A.][Begin Tape 1, Side B.]

MR. TULLY: Before you talk about these foundation courses in college, what was the name of the high school you went to?

MR. CLOSE: Everett High School.

MR. TULLY: And elementary school?

MR. CLOSE: I grew up in Lincoln Heights. I’m not sure what that grade school was — probably Lincoln. Then I lived at Oakland, which is a district of Tacoma, and I went to Oakland Grade School. Then I moved to Everett and I went to South Junior High School and then on to Everett High School and then Everett Junior College, which is now Everett Community College. Then I transferred to the University of Washington at the end of my sophomore year. Then in the middle of my junior year I was given a scholarship to go to the Yale Summer School of Music and Art. I spent the summer between my junior and senior year of college there. On the basis of that, I was encouraged to apply to graduate school at Yale, which I really didn’t intend to do, but the Cuban missile crisis came along. As soon as my student deferment ran out from college, they called me down for a physical which I had been told I would never pass, that I would be 4-F because of my medical problems. But they lowered the standards enough to make me 1-A, so since I wasn’t going to be 4-F and I was now 1-A, I had to get into a graduate school fast. I called Yale and the chairman of the art school –Bernie Chaet — had been the head of the summer program and he had me quickly apply and moved me to the head of the waiting list. I managed to get into graduate school in just a matter of a week before graduate school started. I know we’re jumping way ahead. I just thought I would finish the education while we’re at it.

MR. TULLY: No, that’s good. So what year was that? You said the Cuban missile crisis.

MR. CLOSE: That was 1961 that I was at Yale and then I came back for this academic year of 1961-62. I guess that was when the Cuban missile crisis was –right?

MR. TULLY: I think so, yes. It sounds right.

MR. CLOSE: What ever it was, I remember sitting there looking at the nudes and thinking, “well at least I won’t have to go. I’m going to be 4-F.” [Laughs.] And it didn’t work out.

MR. TULLY: So just going back to Seattle and this idea about going into art school, your idea was commercial art. You knew already probably that artists would have a hard time supporting themselves?

MR. CLOSE: Well, I guess I was beginning to see the sort of Playboy magazine idea of what an artist was. I wanted to be an artist who also drove a sportscar. Whoever that was — those people who were doing cartoons and doing illustrations and whatever– who had that kind of lifestyle interested me. Then, of course, the minute I got into college and started taking painting and drawing and whatever, then I realized that was what I really wanted to do. I took one commercial art course and hated it — dropped out. So I would say it was a momentary lapse of practicality which went by the board.

MR. TULLY: Who was there at the school in Seattle?

MR. CLOSE: This was in Everett — this was Everett Community College– and it was unbelievably fortunate that I happened to live in this town with this incredible art program in a junior college. I mean, it’s unheard of. This junior college — the only thing that distinguished it was its art program. Russell Day, who was chairman of the art department, was probably the most respected and powerful faculty member on campus. It was just this odd thing that happened. They had a wonderful art program. I got a much better first two years of art education than I would have had I gone to the University of Washington and essentially been taught by the TAs. This was a very incredibly rigorous, competitive, demanding program taught by these extremely — there were three members of the faculty — Russ Day, Donald Tompkins, who was my mentor and who since has died, and Larry Bakke, who was the painting teacher. I’ve always been at the right place at the right time. Art schools especially have golden periods and then periods when the chemistry does not work. I’ve been very fortunate to always be someplace when it was the–all of that. I think that I’ve always worked hard. But a number of things have conspired to make things happen — being, I think, essentially driven into art in the first place. Probably more because of what I couldn’t do drove me further and further into art. Then excelling at it –if I had also been good at other things, perhaps it wouldn’t have meant as much to me. Just fortuitous things –like the fact that my father ate breakfast in a diner where this woman also ate breakfast that I ended up studying art. All these things just seem very coincidental and lucky.

MR. TULLY: You mentioned the three faculty people — Russell Day —

MR. CLOSE: Donald Tompkins, and Larry Bakke — were terrific. All three were wonderful. Then when I transferred the University of Washington it also had some wonderful people — terrific people — some of whom are still my friends today. Probably the most important one at the University of Washington was a man by the name of Alden Mason, who is a wonderful painter and a wonderful painting teacher. I have some of his paintings in my studio right now which I’m showing to dealers in New York.

MR. TULLY: What’s his work like? What was his work like then?

MR. CLOSE: It’s always been sort of personal monster kind of imagery that’s painted in a very expressionist way.

MR. TULLY: You must have been quite sophisticated in comparison to other people that were around in terms of being exposed to a lot of art.

MR. CLOSE: Yes. And I was a great student. I was exactly what everybody had in mind. I knew what art looked like and I could make something. Being a good student is a double-edged sword, I guess, because I got lots of pats on the head, I got lots of scholarships, I got grants and stuff — Fulbrights and all that sort of stuff — because I was a good student and because of the relative ease with which I could make things that looked like art. The trouble is, if it looks like art, it must look like someone else’s art or it wouldn’t look like art. When I met de Kooning I said, “How do you do? My name is Chuck Close. I’m the person who’s made almost as many de Koonings as you’ve made.” [Laughs.] It’s true. I was de Kooning or I was Hans Hofmann or I was whoever it was.

MR. TULLY: This would be familiarity from magazines, from —

MR. CLOSE: Yes. Growing up in Everett and Seattle and going to college there was a real cultural backwater. And the mountains are a kind of emotional distancing device. Seattle was not like other cities in America — or wasn’t then. It really drew the wagons into the circle. They loved themselves and they always referred to it as “God’s country” and they hate everywhere else even though they’ve never been there. The whole culture — if there is an interest in culture, which there’s very little, or was in the ’50s, at least — they looked towards the Orient. The art history courses were on Japanese art or were interested in American. They did American Indian art and Eskimo — Alaskan. There was virtually no interest in Western culture. Everybody who traveled had been to Japan. I never knew anybody who had been to Europe. New York was viewed with great suspicion. The heroes — the gods — were the people like Mark Tobey, who had gone to live in a Zen Buddhist monastery in Japan. Of course they overlooked the fact that he then went to live in Ireland or wherever the hell he was. Or was that Morris Graves? But there was tremendous suspicion of New York and those things. I immediately wanted to make stuff that was about New York. Alden Mason was very supportive. He was somebody who would not make great Northwest mystic paintings. To paraphrase Gertrude Stein, as soon as I discovered there was a there there, I went to it. I got out of Seattle, which I saw as an intellectual and cultural backwater, and wanted to go where it really was happening. The other part of being a good student is that it’s very hard then to develop any kind of personal idiosyncratic vision because your hand moves in art ways. It wants to make art shapes. I supposedly had a good sense of color. As far as that’s concerned, I think I had discovered that certain color combinations look more like art than other color combinations. So there were many, many habits and many skills which were developed in school that had served me very well as a student which later became a big problem in terms of differentiating myself from everyone else and trying to find out who I was, different from other artists.

MR. TULLY: So would you say in that period of time when you were transferring over to Seattle — if you were going to bring a portfolio of work — would it be across the board examples?

MR. CLOSE: It’s really funny. One of the reasons that I was sent by the University of Washington to Yale Summer School was that I was — in a sense — a kind of compromise candidate. There were various factions in the school, and I had transferred there recently and I wasn’t identified with any one of those factions. As I studied with a member of each one of those factions, I could do whatever it was that person had in mind. So each camp thought I was theirs. I hadn’t been around long enough to be contaminated in some way by having been identified with any one of those factions. Since none of the factions could send the one that they particularly wanted to send — [they laugh].

MR. TULLY: “I’ve got the perfect candidate.”

MR. CLOSE: That’s right. So it always served me. It wasn’t that I was a whore, I don’t think. It was just that I had pretty good ability to function in many different ways.

MR. TULLY: So what would the range be from one faction to another?

MR. CLOSE: I would paint hard-edge paintings with masking tape, hard-edged paintings with Spencer Moseley. It depended on whose class I was in, I guess.

MR. TULLY: But Moseley was at the University of Washington?

MR. CLOSE: Yes.

MR. TULLY: I was going to ask you before and maybe again if we could just digress for a moment.

MR. CLOSE: Yes.

MR. TULLY: In terms of your childhood friends, did you have contemporaries of yours that were also interested in art or that you talked about — you know, “Gee, did you see that Jackson Pollock?”

MR. CLOSE: I had friends in the art department in high school. I went to a pretty good size high school. We had 2000 students, I think — 500 in the graduating class.

MR. TULLY: Oh, that is big, yes.

MR. CLOSE: So we had a big art program. In fact, the art teacher ran off with my girlfriend. [Laughs.] I was dating this other girl in the art program, and all of a sudden one day she didn’t come in, and neither did the art teacher. [Laughs.] He was like in his 40s and she was of course 16 or 17. Something like that. When I say “poor whitetrash,” I mean poor whitetrash. [Laughs.] This was America. This is out there in this little mill town. It was a real scandal.

I was just thinking that I must sound like this really weird kid. Driven to this. Couldn’t do all these things. The thing that I was always very good at was disguising all of it. Most of my friends didn’t know that I had — a lot of my teachers never knew that I had as much trouble with material as I did because I’d find ways to give them — luckily, back then, people didn’t know about learning disability. I wasn’t pegged. I wasn’t pigeonholed the way a kid would be today. If you’re not destroyed by it, you’re often stronger, I think, because of it. I developed ways of beating the system. I don’t think I was pathetic. Do you know what I mean? I don’t want to create the notion that I’m some weird, pathetic, nerdy kid that nobody wanted to play with. I was very popular. I wasn’t Mr. Popularity, but I don’t think people would have thought of me as being particularly out of the ordinary. People didn’t notice that I didn’t go out for sports and stuff. I just managed to not do it. I did have some sadistic gym teachers, though, who would make me run until I’d fall down and make me get up and run again. There were taunts that were very difficult. But, basically, I think I always managed to make it work for me. I think that if you’re not beaten down by it and if you can beat the system, it gives you a sense of power. It gives you the sense that your destiny in is your own hands — that you just have to find your own way of doing it. It’s just not the way that other people are doing it. And that ultimately nobody else is going to do it for you. You’ve got to find your own solution to each individual problem.

MR. TULLY: I was wondering, for instance, what you had said about these factions and how you wound up being a candidate for the summer school really because of all this crazy politicing, probably. What I was wondering — at that time were you aware of that? That you were sort of able to do these things or was it more of like a kind of naïveté?

MR. CLOSE: I think it was naive, except that one of the members of the faculty pointed out why it was that I was chosen. He was very pleased that I had gotten it, and he told me how I had gotten it. So that’s how I’m aware of the fact. Otherwise I wouldn’t have known what happened in the faculty meeting and why I was the chosen one.

MR. TULLY: Was this the same person that you’ve mentioned–Alden Mason?

MR. CLOSE: Yes.

MR. TULLY: I didn’t ask you where you were living at this point. You were in Everett?

MR. CLOSE: While I put two years in junior college there.

MR. TULLY: Living at home?

MR. CLOSE: Yes. Then I went to Seattle to the University of Washington. We had a number of people in my high school who were interested in art who are still artists who I still see. We went to junior college and transferred to the University of Washington together. I lived in a wonderfully bizarre house full of artists in Seattle — as many as eight or nine of us. Not all artists. We had some other people. We had wonderful parties.

MR. TULLY: What part of Seattle would this be?

MR. CLOSE: In the university district within a few blocks of the university.

MR. TULLY: Do you remember any of these — in terms of names–of someone from Everett that went over with you to Seattle?

MR. CLOSE: Students?

MR. TULLY: Yes.

MR. CLOSE: Oh sure. Two of my closest friends are Larry Stair and Don Trethewey. There are a lot of artists. Michael Monahan is still an artist. Joe Aiken is still an artist. There was a whole bunch of us. Even for people to graduate in art — as you know–very few finally end up practicing it — at least after 15 or 20 years. I was in junior high school with these people. I’ve known most of those people since I was 12 years old and we’re all still artists. There are several others if you want more.

MR. TULLY: Sure. Why not?

MR. CLOSE: Of course, I have to think of them now. Oh gosh. Gee, I’m trying to think of the skinny kid with the pipe. Well–

MR. TULLY: This house sounds very much like in the Playboy tradition.

MR. CLOSE: See, at the time, too, you have to remember that when I got interested in art in the late ’50s, early ’60s, it was a very straight time in America. Art and music school and art and music were a couple of the only areas in which anybody who was not gray flannel buttondown went. I really fell in love with the idea of being an artist almost as much as I fell in love with art. It was a license to dress differently. If you wanted to live with a girl — people in the art school were the only people that were doing that –and use drugs. In the late ’50s and early ’60s, if you smoked pot, you were in the art school. That’s it. Art and music. That was it. Everyone else was so there was a whole lifestyle in the sense that you sort of bought into when you started out to be an artist that certainly — compared to what it was like to be a student a generation later, or now. The only people I know who are still using drugs are people on Wall Street.

MR. TULLY: It’s true. A bizarre twist, really.

MR. CLOSE: Yes.

MR. TULLY: It’s funny, just when you said that about dressing differently. Right then I was trying to get a mental picture. What would be your–

MR. CLOSE: At that time everybody looked sort of like the Kingston Trio. The Lettermen — crew cuts and stuff. Buttondown everything. Buttondown shirts. The pants with the little buckles in the back.

MR. TULLY: Ivy League.

MR. CLOSE: Right. In art school you had late bohemian, pre-beatnik. Of course pre-hippie. Sort of beatnik. What was considered beatnik. Growing up on the West Coast, we spent a lot of time in San Francisco, we spent a lot of time in North Beach. We’d think nothing of driving to San Francisco–over 1000 miles — to see a play. And then while you were down there, you’d spend two or three days camping out on the roof of the San Francisco Institute of Art. It was either the San Francisco Institute of Art and now it’s the California School of Fine Arts or it was the other way around. I’m not sure what it was.

MR. TULLY: Camping out on the roof?

MR. CLOSE: Yes.

MR. TULLY: The people who knew knew about it and did it?

MR. CLOSE: Yes. It was sort of the thing to do. [Jack] Kerouac and all those people were big. Actually, Al Leslie was out there doing “Pull My Daisy” with Gregory and all those people. And Larry Rivers was doing that. It was interesting. William Wiley and Joan Brown were students. This was the late ’50s. They were like the big star students who were going to carry the torch of Abstract Expressionism. The young bucks — and buckettes in the case of Joan Brown — were going to keep the tradition alive. Of course they did it in a different way. But it was a very exciting time. It was all connected with poetry and the Hungry Eye and all these places where young comedians were coming up and lots of Beat poets. Poetry readings and folk music. In Seattle we used to go to poetry readings and folk things all the time. And a lot of jazz. Great jazz in California.

MR. TULLY: And you read the Beats?

MR. CLOSE: Yes.

MR. TULLY: On The Road?

MR. CLOSE: Yes.

MR. TULLY: Did you have a car then?

MR. CLOSE: Oh sure. If you grew up on the West Coast you had to have several cars. All junkers, but you had a car for all occasions.

MR. TULLY: How many did you have?

MR. CLOSE: Probably by the time I graduated from college I had had 10 or 12 cars. 15 cars. I had a 1926 Model T. I had — oh God, I had all kinds of cars. Motorcycles. Everybody had. You can’t be so poor that you don’t have a car. Or two. You’d buy a car for fifty bucks. You didn’t have to have insurance. If that thing broke down, it would sit in the front yard and you’d get another one. It was absolutely so different from my friends who grew up in New York. It was like — you might not have food on your table, but you had a car.

MR. TULLY: And so would you drive? Like go that 1000 miles–

MR. CLOSE: We’d get a bunch of people in the car and just head out. I remember at one point we went down to the play The Balcony. Who wrote that?

MR. TULLY: Was that [Jean] Genet?

MR. CLOSE: I’m not sure who wrote that, but I remember making the trip for that. I can’t remember — I saw some plays when I first came to New York and I can’t remember whether I saw them — I saw The Iceman Cometh either in California or in New York. I saw Rhinoceros, I guess, in New York, so it was about early ’60s — late ’50s.

MR. TULLY: So you were then part of that — as you describe–the beat scene in North Beach and Citylights bookstore?

MR. CLOSE: Oh yes.

MR. TULLY: So you were riding that–

MR. CLOSE: I was a student at the same time. We definitely were like hangers-on. Larry Rivers is enough older than me that he was actually there, as was Alfred Leslie, and he knows all those people. We knew of them. We saw every foreign movie that came out, and we went to every poetry reading that we could. But it was a very interesting time because being an artist set you apart from everybody. Unless you were a writer or a musician or an artist — America seemed to be — Eisenhower was president. Then Kennedy was elected just as I was getting out of college, and was assassinated while I was in graduate school. The effect that Kennedy had was almost more afterwards than during. Kennedy was an incredible breath of fresh air, but America was still Eisenhower’s America. It was very conservative. You had to almost to be surrounded by a group that would support anything out of the ordinary. It was a very difficult time. I’ve had a beard since 1958. I would go years before I would see somebody else with a beard. People would roll down the window of their cars — and this was even true in New York and in New Haven when I came to New Haven to go to graduate school. Nobody had beards. People would roll down their windows and scream, “Hey, Castro!” or if it was near Christmas say, “Santa Claus.” It was that unusual that anybody would have a beard. It’s hard to remember. Now when I get on a subway and I’ll look around and every male in a car will have some facial hair. Then so I said, “Well, I’d better shave my beard.” If I weren’t so lazy I would shave. But at that point I literally could go a year or more without seeing a beard. And if you did see somebody with a beard, it might be some old man or some bum — the equivalent of a Bowery bum. It’s hard to remember now just how straight America was and how little room there was for individuation in terms of clothing. I started wearing very bizarre clothing in the ’60s. I wore ruffled shirts with lavender paisley vests my mother made me. I wore bowlers. I went out in costumes. I essentially wore costumes in the street.

MR. TULLY: In Seattle?

MR. CLOSE: In Seattle, in New Haven, in Europe when I was on a Fulbright. Then — of course — when the hippie thing came along, all of a sudden I would discover while I was walking down the street 12 more people more bizarre than I was. So then there was no reason to do it anymore, and I became very conservative in my clothing. But there was a time when being an artist was a license. It was a very interesting time, I think. It’s hard to remember now how unusual you could be.

MR. TULLY: You said in 1958 you grew a beard. You just wanted to see what it would look like?

MR. CLOSE: I really wanted to separate myself. Wore gray. I walked around with books that I hadn’t read because I always had trouble reading.

MR. TULLY: It would be difficult being dyslexic. Isn’t that a major problem?

MR. CLOSE: Yes. Very difficult. I read with great difficulty. One of the reasons that I like poems, as I like magazine articles, is that they’re short. I can get through something short. And also a poem often — because it cuts through time –doesn’t require remembering the names of characters. I still don’t read novels because I cannot remember the names of the characters. I always have to go back and see — but a poem cuts across time and often makes an image that I can relate to as a visual thing.

MR. TULLY: That kind of atmosphere you’re setting in terms of being in Seattle, being free enough to take off for a couple of days — or more probably — to go to San Francisco and then jazz and poetry and all that — did that start to effect the kind of work that you were making?

MR. CLOSE: I was pretty much making weak, fourth generation, junior Abstract Expressionist paintings. I studied from people who had seen something once. [Laughs.] When I went to Yale Summer School is the first time I actually met an artist who had been in a book and that was very exciting. People I had read about in art magazines.

MR. TULLY: Before that — I don’t want to interrupt you — but I was going to ask you before you went to this summer school did everyone have a studio in Seattle in the art school? Was it like a cubicle?

MR. CLOSE: No. Oh, the graduate students, but I wasn’t a graduate student. I always found space because I worked so big. See, the faculty was very supportive of me. I had faculty members who gave me their old paintings. Really wonderful people. They would find space for me. I also worked at home. We had a big house. We had a six-bedroom house that we rented. I was ambitious. I would make eight by 10 foot paintings — 10 by 12 foot paintings. I was very ambitious.

MR. TULLY: Can you describe one of those from that period of time?

MR. CLOSE: In 1959 and 1960 I started painting flags. I guess I had seen Jasper Johns. I started doing things like that. I got in a lot of trouble. I was involved with some local censorship and stuff. I was in an exhibition and the work would be thrown out. I saw myself as railing against the establishment. To make art that offended. The American Legion would come with a couple of axes and chop down the door and things — was very exciting.

MR. TULLY: So it was the American Legion that you got in trouble with?

MR. CLOSE: Yes. I got in trouble with them — with other groups.

MR. TULLY: When the work was exhibited?

MR. CLOSE: Yes.

MR. TULLY: I guess that would be a question I haven’t asked you, in terms of your exhibition history.

MR. CLOSE: As a talented student, it was possible to show in the same exhibitions as the faculty. I was in the Northwest Annuals at the Seattle Art Museum. I won prizes and got money and blue ribbons and all this stuff and all these things. One of the paintings was a flag in the Northwest Annual– which is the biggest exhibition in the Northwest — at the Seattle Art Museum. Charles Fuller — who was the founder/owner of the family of the chairman of the board of the Seattle Art Museum — came after the jury had awarded me third prize and I think $1,000 and threw the painting out of the show. Some of the jurors left in protest. But I was always interested in provoking. Now I see it as very sophomoric and whatever, but in a local, regional way it was always possible to provoke controversy. I had a painting in a show in Pulliam that the American Legion literally came and chopped the door down.

MR. TULLY: Where is that?

MR. CLOSE: It’s near Tacoma. It was a big regional show.

MR. TULLY: You’re not exaggerating when you say the American Legion had chopped the door down?

MR. CLOSE: Yes. Well, there was a Pulliam Fair. It was a big state fair and they had a regional art exhibition. This guy — Don Scott, a friend of mine — was involved with that. He was on the State Arts Council or something like that at the time and he literally saved the painting by stopping them.

MR. TULLY: And they came during the —

MR. CLOSE: I don’t remember now what the specific–

MR. TULLY: And what were you doing exactly with the flags?

MR. CLOSE: I was cutting them up and sewing them together as a kind of — it was “ban the bomb” kind of stuff. I would take a flag, cut it up —

MR. TULLY: An American flag?

MR. CLOSE: An American flag. Cut it up, sew it back together in the shape of a kind of mushroom cloud, paint on it with words like “e pluribus unum” and all this sort of stuff, and December 7, and all these other things. So they were vaguely against military, against nuclear — the Korean War was over. We were in the heart of the Cold War.

MR. TULLY: Now where did you learn how to sew? That was something you picked up?

MR. CLOSE: Oh, just big stitches. I would take like a five by eight foot flag, and cut it up, and then sew it back together and it would be in a canvas that would be eight by 10. Let me see if I can find a slide.

MR. TULLY: Okay.

MR. CLOSE: Here’s one.

MR. TULLY: From the slide it looks like a very painterly.

MR. CLOSE: Oh yes, very painterly.

MR. TULLY: Do you have any idea what happened to the painting?

MR. CLOSE: Yes, it’s in my mother’s husband’s house. My mother’s dead.

MR. TULLY: When would she have remarried?

MR. CLOSE: Not until after I married. This is a very dark slide, but this is the kind of painting that I was doing at Yale. This is basically a seated figure, but a very kind of —

MR. TULLY: So it’s a, kind of, side view?

MR. CLOSE: Yes.

MR. TULLY: And very large.

MR. CLOSE: Yes.

MR. TULLY: Is that you sitting next —

MR. CLOSE: Yes. This was about as figurative as the work got at Yale. This is a reclining figure with one leg in the air. This is an unfinished painting. This is a huge painting.

MR. TULLY: 59 by 90!

MR. CLOSE: This one — this was not at all the way the painting looked at the end — which became almost monochromatic at the end, but it was basically the pink angel combined with [Arshile] Gorky and all kinds of other stuff.

MR. TULLY: You’re not kidding! Wow.

MR. CLOSE: There are a couple more of the general kind of figurative — I can show you what I was doing at the University of Washington.

MR. TULLY: It sounds like you really have held onto a lot of work.

MR. CLOSE: I don’t have very many of the paintings.

[End of tape.]

[May 27, 1987, second part of interview with Chuck Close.]

MR. CLOSE: We always went to whatever Protestant church was just down the street. We were Methodists, Presbyterian and Baptists. My mother got quite involved in the church after my — before my father died they were as well, but then after my father died we moved back to Everett, and my mother became very involved in the church, and was on the Board of Trustees and the choir director and the organist and the Sunday School teacher and all that sort of stuff. I actually taught Sunday School for a while myself when I was in high school.

MR. TULLY: What was that like?

MR. CLOSE: I think finally the hypocrisy of organized religion in America became just sort of unbearable. It was a very narrow community full of prejudices and hatreds, so there was this conflict between the stated intentions and the piety and whatever. I remember in my high school Baptist youth group, my girlfriend and I were the only two kids that didn’t have to get married. Virtually the entire group had shotgun weddings. Not that that’s so surprising, I suppose, except that it was the —

MR. TULLY: It depends on how big the group was.

MR. CLOSE: [Laughs.] Yes. It was just the difference between the stated moral or ethical position than what in fact was going on. My mother left the church when after all those years of service — she was selling real estate at the time — and she tried to put a Mexican American family into the parsonage. The church had an empty parsonage, and they thought it was fine that it be rented until they found out that it was a Mexican American family and then they refused. So my mother left the church at that point.

MR. TULLY: And would that go kind of unreported? Was she outraged?

MR. CLOSE: I guess anyone watching the Jim and Tammy Bakker thing on television unfold — there’s a real connection between repressed, very narrow parameters of how one is supposed to live — remember that there was no smoking and no drinking, no dancing and no anything. So for everyone to be screwing around in an environment in which you weren’t supposed to even smoke or drink or dance is–anyhow, it always had a big effect, I think, on –I am very moralistic and I’m not religious, but I think I tend to see things in a black and white way. I think that probably is an outgrowth of that kind of thinking. It’s taken me years to find the grays — to find any pleasure — for somebody who makes black and white paintings – in the middle ground. I’ve always found extreme positions interesting. Frankly, I think the art world is an interesting place for extreme positions to come up. I remember once — I don’t remember if I mentioned this last time you were here — were we talking about when I was working with Richard building sculptures?

MR. TULLY: No.

MR. CLOSE: Because at one point when we came to New York I used to help Richard Serra build his lead sculptures — prop them up and stuff. He used to come to my studio and look at my paintings and I would go up and look at his stuff. It was — at least for me — an important time in my life as a young artist. I remember something Richard said about how to end up making work that didn’t look like anybody else’s work, which even now seems kind of curiously out of date with today’s interest in appropriation and the ease with which one raids the cultural icebox. But at the time, I think everyone wanted to separate himself or herself from everybody else and not have the stuff look like art. That was the whole appeal of going to Canal Street and finding materials that have never been used to make art before, so that they came without any art world association and no particular way to use them. Nobody wanted to make bronze. Now everyone’s making bronze sculptures. Then, anybody who was making bronze was considered just hopelessly lost. So they would try to find rubber and you would see what it could do. You bounce it, you lean it, you stack it, you scrunch it — whatever you can do to it. So at any rate, I remember once (in terms of this notion of extremism or whatever) that when Richard was in my studio he was talking to me about my work and he said, “You know, if you really want to separate yourself from everyone else, it’s very easy. You don’t even have to think. Every time you come to a fork in the road, automatically one of those two routes is going to be a harder route to take than the other. So automatically take the hardest route, because everybody else was taking the easiest route. If you take that least likely, most extreme, most bizarre, hair shirt, rocks in your shoes kind of position — since everyone else is doing the kind of proof of what is the prevailing wisdom — you will make idiosyncratic work. You will push yourself into a particular corner which no one else occupies.” I think that was very much about what the times were like.

MR. TULLY: How did you take that at the time when you first heard it?

MR. CLOSE: I thought it was interesting advice for somebody who was now making paintings that took months and months just putting thinned down, watery black paint on canvases and slowly building this imagery in a sort of odd, somewhat mechanical way.

MR. TULLY: Describing your work?

MR. CLOSE: Yes. I think that extreme positions — Barry Goldwater not withstanding [laughs] — are what changes what art looks like. It seems to me that the art world — I know this is a digression from talking about where I was — is that okay?

MR. TULLY: Yes, that’s fine.

MR. CLOSE: When I was a kid, I was outraged when I saw my first Pollock because it didn’t look like art. I remember the same sense of outrage the first time I saw Frank Stella’s black paintings and to a lesser extent the first show I saw of Warhol’s at the Stable Gallery. It’s still possible to have that feeling when you see a [Jeff] Koons show or something like that now perhaps. I’m not particularly outraged, but some people are, I guess.

MR. TULLY: Are these like the submerged basketballs in the aquarium or something like that?

MR. CLOSE: Yes. Right.

MR. TULLY: It’s Jeff Koons?

MR. CLOSE: Yes. Or the Jim Beam decanters that all our fathers had over the bar. My family didn’t drink, but friends’ families that had a bar. My family was a firm contributor to the Washington State Temperance Society. At any rate, it seems to me that the art world — if it can be seen almost like from flying above it — if you were to look down at the art world it’s an amoeba-like shape. Sort of a boundary of what art at any one time looks like. It encompasses like a wing out here and it juts out a little peninsula in another section, which covers a certain group of people. And everything that is within that boundary — I think the thing’s a sort of national outline or whatever — is art. Everybody knows what it looks like, accepts that it is art and once you know what art looks like, it’s not hard to make some of it. But it must look like somebody else’s art or it wouldn’t look like art. So everything that’s inside that shape is known and to one degree or another tolerated — or if not loved. You can choose your area. You can go take an area that’s not been very heavily trafficked and work in that area. Or you can go off in some other corner where everyone seems to have congregated, because that’s the prevailing sensibility at the moment and everybody’s mining the same area. At that particular moment — when that’s what art looks like — everyone is solving problems. But the problem was not defined by them. The problem was defined by the art world, so that in the ’60s or in the ’70s or in the ’80s everybody knows what art should look like. It should be this big, it should have an active surface or it should have a non-surface — a virtually no hand, or no gesture, or it should be expressionist or it should be systematic — whatever the kind of thing at the moment is. For whatever time that shape is different than it’s going to be 10 years earlier or 10 years later. But at any given time outside of this shape, some individual makes something and for a wonderful, brief moment in time that stuff doesn’t look like art. It doesn’t look like anything that’s going on inside the amoeba-like shape. It seems outrageous and it seems to question everything that we held to be true about art and whatever. There’s that wonderful brief time when you can look at it almost as if it were an alien species or something — not art. Then within a very short time — this is the wonderful thing about the art world — it seems to me as opposed to other professions where the parameters are set and imposed and you always must work within them and everybody agrees that this is how it’s done — the art world is this totally flexible, organic entity that now sort of — again to use the amoeba metaphor — sort of goes out and envelopes this foreign body, digests it, incorporates it into its own living matter and tugs it more closely to the mainstream, tames it, makes it more acceptable in some way — changes it because of its acceptance. Of course, everyone will run to it, and copy it, and work out of it, and it has influence. So now the resultant outside shape of the art world is changed because that individual existed. And from now on, that area that was formally outside of the shape is now captured territory that also looks like art and also is an acceptable area for people to mess around in. But the important thing is that the art world is capable of incorporating it and not keeping it outside. I suppose it could be said that the true outsider of what we consider to be primitive cultures or the insane or whatever can sometimes stay outside, but then you have a [Pablo] Picasso working from African sources or a [Jean] Dubuffet working from children or the insane. So it gets incorporated in one way or the other. I guess that was what the late sixties and early seventies were really about for me. There were people out there attempting to operate outside of what the conventions were dictating and what the prevailing wisdom and preferred sensibility of the moment dictated. Like I said, that’s why people were looking for materials that didn’t have associations — you didn’t bring that baggage with you into the studio — and why I was interested in trying to back myself into my own corner. And the other people I came to New York with by and large were doing the same thing. I suppose we will talk about that more when we talk about —

MR. TULLY: Yes. Because what you’re bringing up now, it’s maybe that baggage as you speak of it that you left behind at some point, but that you certainly accumulated in art school. May we should bridge that point when you first went to the Yale Summer School.

MR. CLOSE: Right. Like I think I said last time, I sat in Seattle not knowing what New York art looked like. Occasionally a piece would come through. The Seattle World’s Fair happened in 1961 or something like that. Sam Hunter did the “Art Since 1945” show and that was one of the first opportunities we had in Seattle to see not only Hofmann, but de Kooning and Pollock and all those people, but also all the Europeans, because it was a very inclusive show. I remember Skira did a book called Current Trends or something like that.

MR. TULLY: Current Trends? I’m not sure.

MR. CLOSE: It was a big blue — Contemporary Trends. And it had [Roger] Bissière, [Pierre] Soulages, Europeans who were making stuff that most of us had no knowledge of in Seattle. The first time we had seen any of that in color. Looking at black and white reproductions in art and you’d need a magnifying glass — that is my recollection of what it was like to be an artist in Seattle. Trying to figure out what the hell the surface must have looked like. Trying to imagine what color these things came in. Because at that point — and it really was a service that art museums used to do — they used to review every first one-man show, along with eight hundred people that you’ve never heard of since. But there often were these little teeny black and white reproductions of what was the cutting edge of the most difficult work. There’d be a full-page color reproduction of a Titian, but I wanted to know what color the de Kooning was — not the Titian. So I think there was a lot of misunderstanding. When I first saw some of those things in the paint I was struck by how different they were — how much smaller they seemed. Also the first color things I saw in the Skira and other European books had very heightened color. The actual paintings were — in some cases — kind of disappointing to find that they were much more drab than it had appeared in reproduction. So when I came out in the summer of 1962 to go to Yale Summer School I came first to New York City, where I spent about two or three weeks. God, I was a real Midwest or Western hick kid, so naive, so trusting. I remember that I got out at Penn Station. Well, just to go into Penn Station —

MR. TULLY: This is the old Penn Station? The one they tore down?

MR. CLOSE: Yes. And standing there with my suitcase looking up at this cavernous iron structure was just mindboggling. And going out on the street not knowing — of course, being dyslexic, I had never read a book so I had never read a guidebook. [Laughs.] Anyone else who was coming to New York for the first time might have done a little research and figured out where they might want to stay or where —

MR. TULLY: Just cold?

MR. CLOSE: Just cold. Out on the street. So then I realized I didn’t have any place to go. I had my suitcase. So I stopped a cab and I threw myself on the guy’s mercy. I said, “I know that you can drive me around the same block for 10 minutes and I wouldn’t know the difference and you could let me off exactly where I got on. Please don’t do that to me and please take me to a hotel that I can afford that’s safe.” The cab driver was terrific and he said, “Well, where do you want to go?” I said, “I want to go to museums so try to find a hotel that’s convenient.” I guess the only museum he knew was the Museum of Natural History because he put me in the Upper West Side in the — what’s that incredible hotel on Broadway?

MR. TULLY: The Ansonia?

MR. CLOSE: The Ansonia. At any rate —

MR. TULLY: So he dropped you off at the Ansonia?

MR. CLOSE: Yes. So I saw a lot of plays, museums, galleries. It was summer, so a lot of galleries weren’t open. The shows I got to were fine. I got to see a lot of them. It was incredibly exciting for a kid from the Northwest.

MR. TULLY: And this was really the first time? You took a train from Seattle to New York?

MR. CLOSE: No. For that trip, a guy who worked with my mother was going to visit his dying mother in Boston, so I guess I took a train from Boston to New York.

MR. TULLY: What was the Ansonia charging in those days? Do you remember?

MR. CLOSE: I had a really crummy little room. It was quite cheap. I don’t remember. I know it was very cheap. Tiny.

MR. TULLY: And dark probably.

MR. CLOSE: Dark and filthy. But the thing that really amazed me — I said this recently in an interview and somebody was saying that it was their recollection, too, of what it was like to be in New York. I think that for a lot of America, class distinctions really limit what you are exposed to. If you don’t go to certain schools or your family doesn’t have a certain kind of position in the community, certain things aren’t open to you. You’re never going to see them. You’re never going to hear them. One of the things I found really amazing about New York and about coming here that seems so wonderful to me was that I could see the same art for free that anybody else could. That nothing was going to keep me from having as much exposure and the galleries tremendous service. These places were open and they were available. I could go in and ask to see the work of somebody who wasn’t showing that month, and clearly I was not a customer. I was never going to buy one of these paintings. They would take me into the back room and they would drag out paintings of somebody I was interested in seeing. I could see them. I could go to museums. I could go to libraries and reading rooms where I could go into the print room and I could sit and –I don’t think you can do this anymore, but you could go through a stack of Rembrandt etchings and you could look at them. It was an incredible opportunity like that, and I think that people who’ve grown up in the East take what’s available for granted. But boy! When you’re coming here from someplace where this stuff doesn’t exist — so anyhow, I felt so privileged. I didn’t have to be a person of means, a prep school kind of kid, to have this laid at my feet. So it was really thrilling. I saw great theater. Wonderful stuff. Then I went up to Yale Summer School, and it was the first time that I had ever met in the flesh artists that I had read about in books or magazines.

MR. TULLY: So who were some of those?

MR. CLOSE: Elmer Bischoff. The regular faculty was Bernie Chaet, who ran the school and Richard Wydal was one of Sixteen Young Americans that year or the year before.

MR. TULLY: Richard Wydal?

MR. CLOSE: He had a promising, but truncated career. I’m trying to think who else was there. Phil Guston. It was a wonderful summer. 35 kids who were big ducks in their various puddles from all over the country came together and were painting in this barn.

MR. TULLY: Where was it exactly?

MR. CLOSE: It’s in Norfolk, Connecticut. It’s near Litchfield. Beautiful part of the state on this wonderful old estate with a music shed, which was a wonderful wooden concert hall. The music school had the Guinari String Quartet and things like that there that summer.

MR. TULLY: We’re talking about 1961?

MR. CLOSE: Yes. I went back to teach there in 1971 and 1972. It was a great place. At any rate, the other classmates — Brice Marden was there from BU [Boston University]. There would be hundreds of reviews. Each one was 10 or 12 words long. It wasn’t much of a review, but when you’re out in the boondocks and the new names each month–I love art magazines. They’re my passion. I go back over them all the time. Rauschenberg had [Boston University]. David Norcross was there from someplace in California — U.C.L.A. or something. A number of interesting people. Vija Celmins. Do you know her work? She’s from L.A. She shows at McKee [Gallery, New York].

MR. TULLY: I think I know her.

MR. CLOSE: She has drawn water with pencil. Just the waves. Lately she’s been doing sort of fake rocks. A very interesting artist. She’s Latvian. A number of other interesting people.

MR. TULLY: And you took numerous courses or was it one studio course?