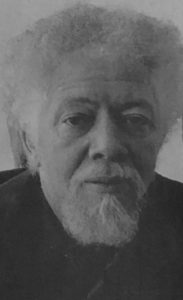

A man of extraordinary insight, talent, and commitment, Benny Andrews rose above prejudice to establish a distinguished career as an arts administrator, lecturer, and artist.

BENNY ANDREWS is talking a blue streak in a quiet bar on the edge of Manhattan’s SoHo district. One hand jabs the air for emphasis and you notice its graceful strength. The voice is rich and melodic, a touch of the South, a definite clip to the aerobic mosaic of words that never seems to require pause for breath. Benny Andrews is talking about his art.

BENNY ANDREWS is talking a blue streak in a quiet bar on the edge of Manhattan’s SoHo district. One hand jabs the air for emphasis and you notice its graceful strength. The voice is rich and melodic, a touch of the South, a definite clip to the aerobic mosaic of words that never seems to require pause for breath. Benny Andrews is talking about his art.

Looking at the untouched glass of white wine as if it were a crystal ball, Andrews—looking much younger than his fifty-seven years—ruminates on his role as a black artist: “I don’t want to be a token but by the same token “—the listener discerns the continual play on words wielded by the calm speaker—” I don’t want to deny what I am. I fight very hard for black artists. I want to be able to be whatever I am. Society is not ready to accept that. That’s why I fight.”

The talk shifts to his recent Italian sojourn, fueled by a Rockefeller Foundation grant, to continue working on a portrait series that the artist had spoken of two months before in his West 26th Street loft. In a matter of minutes, his biographical landscape takes shape and politics segues into aesthetics. Before the last sentence seeps in, he’s on new ground and moving fast through the thicket of art critics and magazines that foster benign neglect.

Finally, you understand his burgeoning frustration when he says, “it bothers me the most not being seen as a complicated individual. It’s much easier to be typecast as regional or representational or Southern or black.” Andrews’ background reads like a novel and, in fact, his younger brother, the novelist Raymond Andrews, has written extensively on their childhood in rural Georgia. Three of his critically acclaimed novels, Appalachee Red, Rosiebelle Lee Wildcat Tennessee, and Baby Sweets, are illustrated by his older brother.

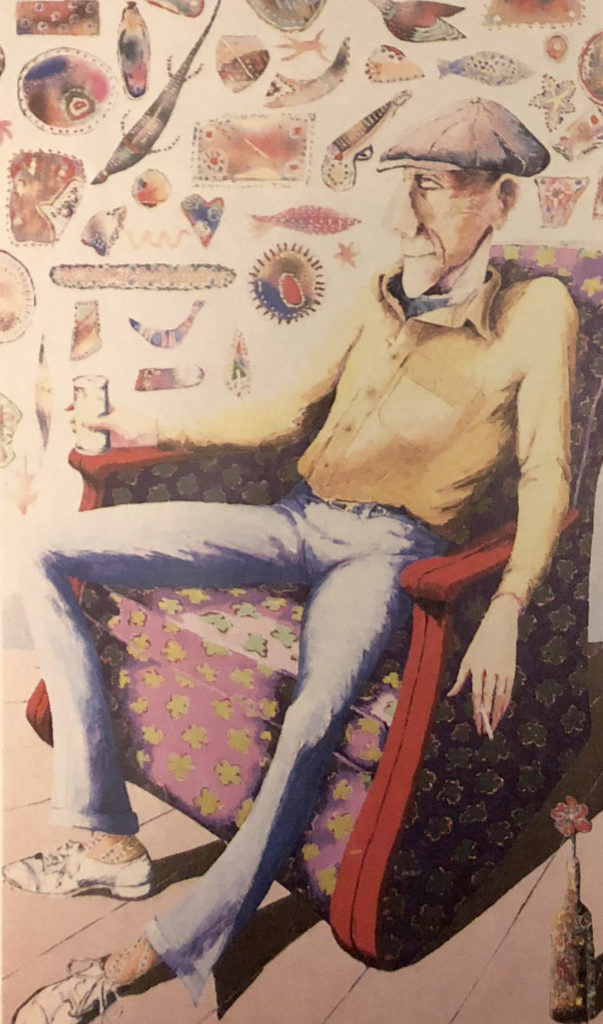

Portrait of George Andrews, 1986, 84 x 50 inches, collection of the artist

For starters, Andrews’ parents were sharecroppers and raised a large family in a glorified shack. The artist started drawing the heroes of his youth, mostly cowboys from the silver screen. Of mixed race, growing up dirt poor in the segregated South, he received little formal training. Raymond, in writing the catalog introduction for his brother’s show at Memphis Brooks Museum of Art in 1986, drew upon his wonderful prose style: “Momma always prayed that Benny would grow up to be a drawing artist rather than a ‘pouring’ artist, another talent of his, the ability from age five to pour water inter-changeably from bottle to bottle without spilling a drop, the mark of a moonshiner. This, Momma claimed, Benny got from Daddy’s side of the family where it was said stretched a long line of perfect pourers.”

The tug of war between good and evil is a recurring theme in Andrews’s work, but his mother’s prayers were answered when the Korean War tore him from his fate-tempting, Southern roots. After an Air Force stint, he returned home in the summer of 1954, ready to take advantage of the G.I. Bill. As providence (or Viola’s prayers) would have it, there was no art school in Georgia that would accept blacks and the state gave the twenty-four-year-old war veteran round-trip train tickets to Chicago so he could enroll at the Art Institute. Segregation had shot Andrews out of Georgia and the next four years transformed him into a citified artist, ready for a whack at New York City.

But the complex transition from country boy to air corpsman to art student was not a seamless one. Andrews embraced Chicago’s blues clubs and drank in the architecture of that fine city. But he also felt at home with the small group of black men—the janitors at the Chicago Art Institute—who cleaned up the turpentine spills and such of the students. Janitors at Rest (not shown), painted in 1957, is his first mature work, utilizing collage techniques. As Andrews tells it, the janitors hung out in the basement men’s room, talking and sipping whiskey from the bottle.

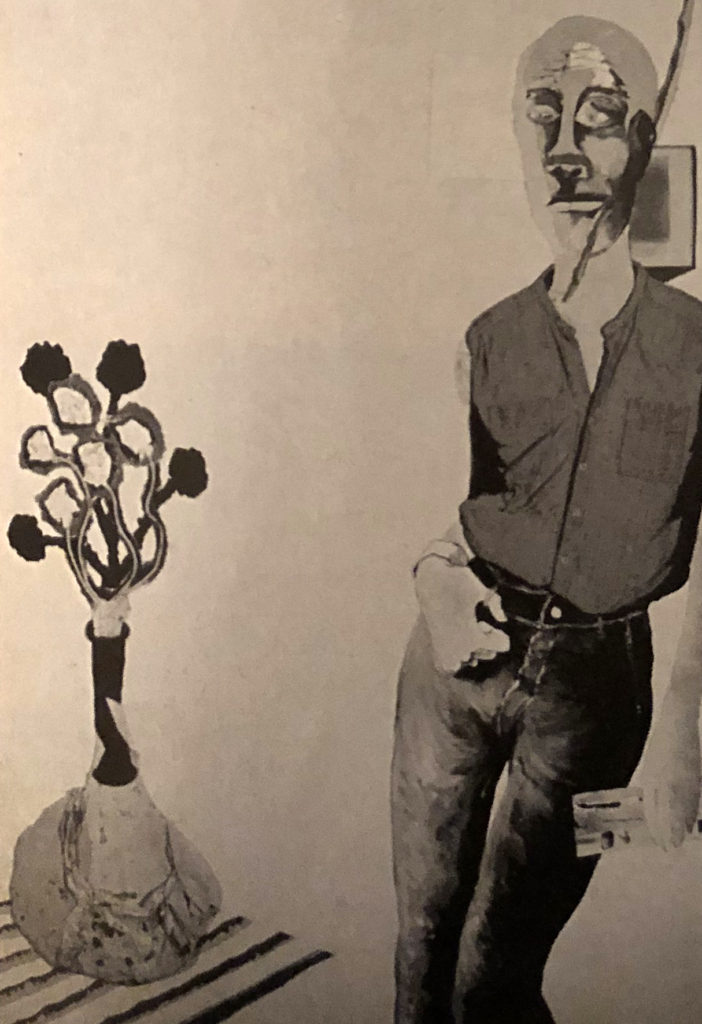

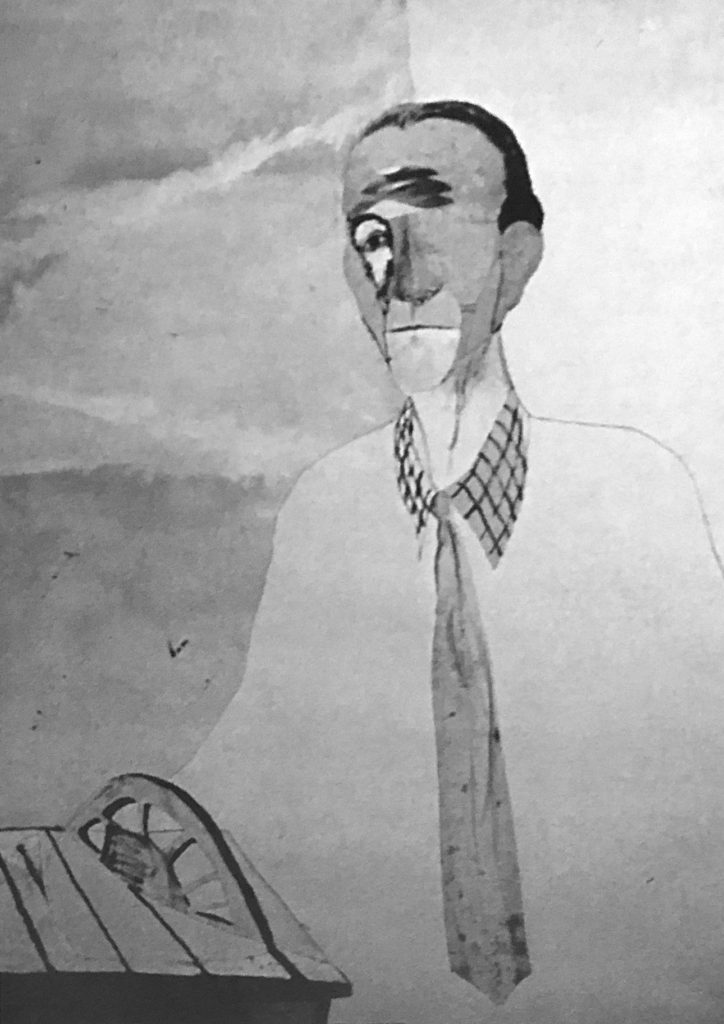

Portrait of Ray Johnson, 1986, 72 x 50 inches, collection of the artist

“They were constantly getting up and mopping up our messes. Then they’d go back to the john and sit,” recalls the artist as he leans the thirty-year-old canvas against a newer work in his packed studio. The composition jumps out at you; it’s an expressive portrait blurred with movement. His metaphorical vocabulary emerged with collaged bits of crumpled paper towels and toilet tissues applied to the canvas. The figure simultaneously sits on a stool, blue-sleeved work shirt rolled up to the elbows, a line of plumbing pipes snaking along the floor behind him and then—bam!–the man is up and running to the next disaster. You can see the influence of the English painter Francis Bacon—and indeed, Bacon was a hero to that generation. The collage elements, though, are Andrews’s device and their abstract quality allowed him to forgo “polishing the apple,” his term for carefully embellished realism.

There’s a picture of Andrews, ca. 1958, sitting on the rooftop of his Lower-East-Side apartment house, look-ing scrawny despite the leather flight jacket. It was a tough time to raise a family in a neighborhood that still defies gentrification. It would be a long four years before his first New York City solo exhibition, but you can tell by the concentration on the young man’s face that he was ready for battle. Today, the artist is represented in the collections of major museums, from the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, DC, to New York City’s own twin towers of culture, the Museum of Modern Art and The Metropolitan Museum of Art. His exhibition itinerary for 1988 re-quires a map to track shows in Michigan, New York, Ohio, Atlanta, Washington, DC, and finally, at the tail end of the year, a solo show at the Studio Museum in Harlem. But when you look back at his first New York City show (at the Forum Gallery in 1962) through the eyes of magazine critics, you see that the work did not trigger raves. If anything, the reception was ambiguous. “I’ve always been an enigma for everybody,” explains the artist, perched on a stool in front of his drafting table. A sign overhead urges in big letters, Silence, and underneath, in smaller type, the explanation Genius at work. Despite the warning, a steady blaring of truck horns from the street below invades the studio.

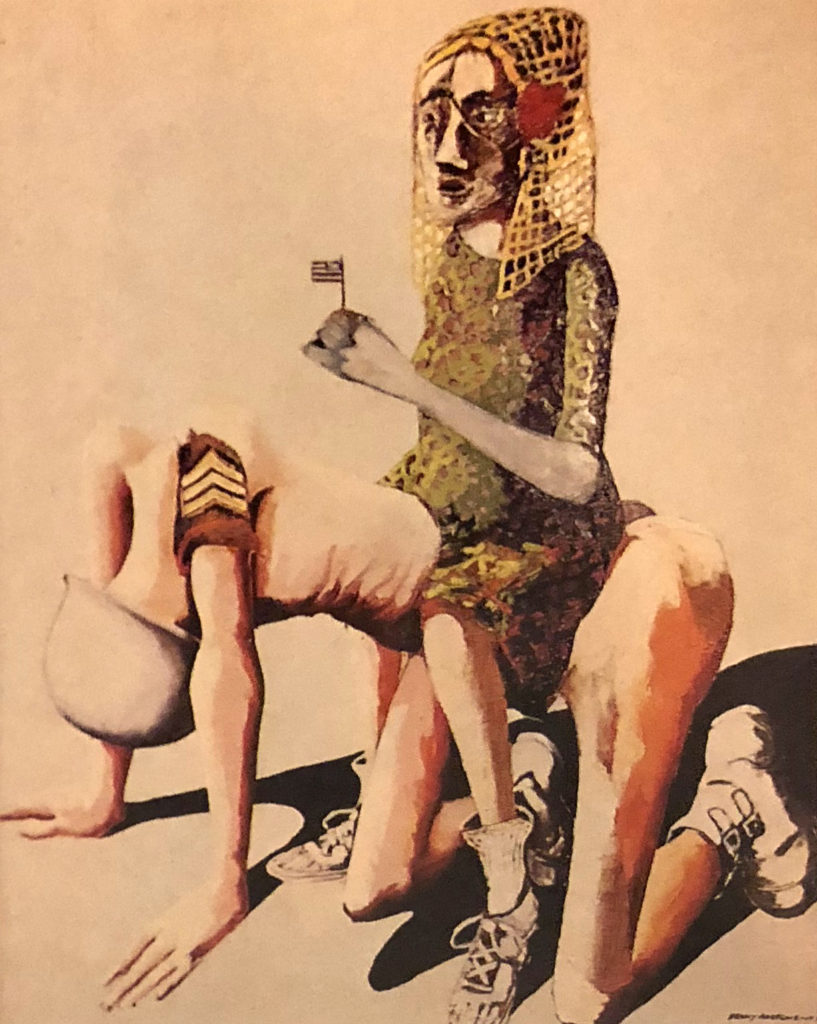

American Gothic, 1971, 60 x 50 inches, Collection of Metropolitan Museum of Art

Andrews’s steady use of collage has always bugged critics and fellow artists, he says, who felt that either “the patches messed up the figurative stuff or, from the other camp, that I used too much figuration.” It is impossible to see in reproduction, but Andrews is rarely satisfied with bare canvas and paint. He wants to inject part of the real world, so his recent portrait Despair (not shown) has cutout strips of faded blue jeans clinging to the young man’s legs as well as fragments from a worn cotton shirt patched across his shoulders. Tension rises between the minimal background and rough-textured canvas sneaker that seems to kick out at the viewer in a silent rage. The figure of the young man, hunched over with head buried in his hands, is the artist’s nightmarish vision of youth hooked on the cocaine derivative popularly known as crack. The youth’s hands are clenched and he appears hopelessly stuck on the box he’s seated on. It might as well be filled with dyna-mite.

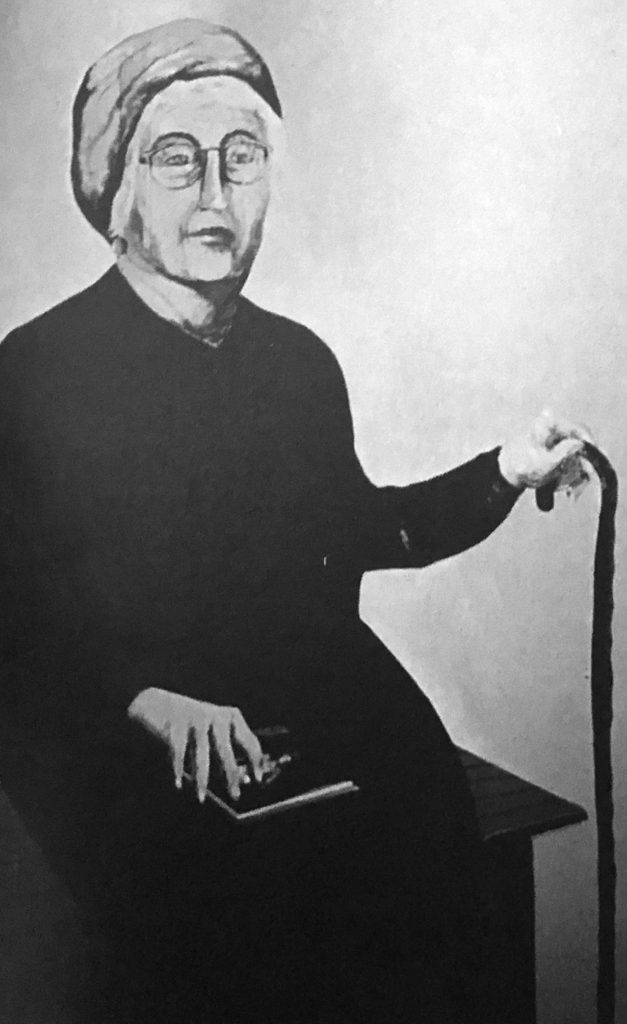

In a seminal portrait of his dear friend the late Alice Neel, Andrews depicts her larger than life—a fur-hatted lioness, outfitted in a preacher’s black frock. One hand grips a gnarled cane while the other rests on her lap, caressing the glossy catalog cover featuring Neel’s portrait of her granddaughter. Her face and hands are collaged folds of canvas, giving the work a kind of clunky Cubism, just enough relief to let the golden spectacles perch atop her Roman nose.

The portrait series embraces not only artist friends such as Vincent Smith and Ray Johnson but his own mother and father, Viola and George Andrews. Portrait of Viola Andrews depicts the devout woman in Whistler shades of black and white. Her somber outfit is offset by the floral wallpaper patterns and vase of fresh flowers soaking in that Georgia sunlight. A Bible is open on her lap and you know the woman can recite the pas-sage by heart.

Portrait of Alice Neel, 1985, 85 x 54 inches, Collection of the Artist

In stunning contrast, the figure in Portrait of George Andrews is loose and sprawled on a comfortable arm chair, a cigarette dangling from one hand and a beer can in the other. Mr. Andrews is surrounded by a wall of his artistic creations: sculpted and painted fish, flowers, wildlife, and other brightly painted organic shapes.

Not surprisingly—but only after you’ve heard with your own ears Andrews’s maxim, “For me, the purest art is the idea, and no matter what you select, the medium becomes second-hand”—Marcel Duchamp looms large in his Olympus in Portrait of Duchamp. Although Andrews never met the consummate idea man of the twentieth century, Duchamp is brought up in conversation again and again, as the artist struggles to define his sensibility. The now familiar white background shrouds Duchamp who glares at us with just one eye. He’s seated next to a plain tabletop but instead of a bowl of fruit of flower vase Duchamp’s sculptural icon from 1913 bicycle wheel assumes the still life element. Andrews employs artistic license here substituting a table for Duchamp’s “readymade” high stool. A mischievous sparkle animates the artits’ eyes as he treads dangerous ground, swatting some realist myths. “I’ve always worked representationally, but I’ve gotten as much from the works of abstract artists as I’ve gotten from realists. In fact, today I find I’m more impressed by abstraction than I am by realist or representational artists. I get more pleasure from looking at a still life of apples by Cezanne than a prizefighter by George Bellows getting knocked out of the ring.

“My major problem with many realistic artists,” continues Andrews, “is their lack of ideas. I think too many realistic artists count on their subject matter to carry their work. They also seem to get lost in creating realistic images and lose sight of expressing the essence of what they’re representing.” With those barbed words, Andrews volunteers that his two favorite artists are Franz Kline and Jan Vermeer. Anticipating the next question with a broad smile, Andrews says, “For me, Vermeer expresses much more than you visually see.”

Potrait of Duchamp, 1985, 52 x 36 inches, collection of the artist

Kline, Vermeer, Duchamp, and Picasso are a far cry from the Social Realist camp Andrews is usually identified with. Part of his enigma stems from his political activism and burningly satirical paint-brush. In the middle 1960s and early 1970s, he championed the cause of black artists excluded from New York City museums and art magazines and made enemies by his outspokenness. The best known protest was against the Whitney Museum of American Art in the Bicentennial year 1976 for staging “300 Years of American Art,” from John D. Rockefeller III’s private collection. Andrew’s gripe was simple: there were no blacks represented and just one woman artist. Andrews jests that he won’t be in any Whitney Museum show anytime soon.

Moving from his studio to study further back in the loft Andrews flicks on an illuminated contraptition to view slides. While he rummages for a to particular set, I skim the crowded book shelves bearing thick volumes, including a dog-eared, leather-bound set entitled Gallery of Famous Painters (as it turned out, I didn’t recognize any of the names).

Five Rolodexes hog the top of his pigeonhole desk, attesting to the artist’s other roles as lecture circuit speaker and occasional bureaucrat (he ran the Visual Arts Program of the National Endowment for the Arts from 1982-84). By this time, plastic slide sheets litter the floor, and, exasperated, Andrews changes the subject to speak of an impending book project on his life and art to be published by the University of Georgia Press. A smile crosses his face as he says, “You know, my life is filled with ironies. I couldn’t attend the University of Georgia when I came back from Korea. Now they want to do a

book on me.”