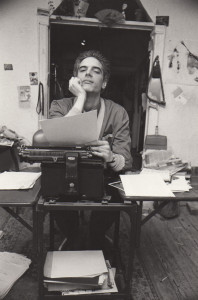

Judd Tully at 187 Chrystie Street, photo credit: Sarah Wells

This interview was originally published on brianappelart.com

Judd Tully is editor-at-large for “Art + Auction” magazine published monthly in New York by Louise Blouin Media.

BRIAN APPEL: Tell me a little bit about how you got started writing.

JUDD TULLY: I came to New York in the early seventies–I had been in Northern California and I was looking for something to do in New York in terms of writing journalism.

BA: So you were writing before.

JT: Sort of. Yeah. Right out of college I was writing for these underground newspapers in Berkeley, California.

BA: Oh, really?

JT: Yeah, “The Berkeley Barb”.

BA: Oh, wow.

JT: Yeah. The Barb was supported by pornographic ads in the back.

BA: Of course!

JT: Anyway I stumbled, literally, into this exhibition. I didn’t really know what it was. It was an installation of Red Grooms in Ruckus, Manhattan which was an installation—he called it a sculptural novel. At the time, New York City was completely bankrupt and the World Trade Center was still standing. It was basically a new building but it was empty.

BA: Hollow.

JT: So Grooms built a miniature model of it, but with “For Rent” signs crudely made on the outside. He had maybe 30 young artists who were working for him making the Woolworth Building, the Brooklyn Bridge, and when you walked through a subway car with figures in it, it would rock; it was on springs. And I thought it was really cool.

And I wound up writing about it. And there was a publication at the time called “The SoHo Weekly News” and I just submitted it—the article.

BA: And it went.

JT: Well yeah, I mean, I was interested. I’d seen the paper and they published it and then I started writing some stuff for them, and one thing led to another. And a lot of the artists who were working for Red Grooms at the time were my age—were young then, and so I met a bunch of artists. So when they would have, say, several years later a show somewhere they knew me and they said hey, can you write something?

So it’s sort of bits and pieces. And I wrote a review in “Flash Art” magazine in the early to mid-eighties when Jeffrey Deitch was the New York editor.

BA: The MOCA director-to-be.

JT: Oddly enough. Anyway, I found out that I couldn’t support myself even with part-time jobs writing criticism. Well, it wasn’t criticism, it was more like art reviews.

And I switched more to journalism. And then I wrote for “The New Art Examiner” in Chicago. I went to the Museum of Modern Art library. I used to hang out there and look at publications. And I liked that publication, contacted them, and then started writing stuff about New York for them. And then it gradually—I got very lucky in the mid-eighties—and started freelancing as a stringer for the “Washington Post” for the style section. And then wrote a tremendous amount of stuff on auctions. Not that I knew anything about them.

That’s how I fell into it.

BA: Oh, okay.

JT: It’s like falling into a ditch. Stumbling and falling into a ditch.

BA: That’s great. I had no idea. Where were you born?

JT: Chicago.

BA: Okay.

JT: Then I was living in—I dropped out of graduate school and –

BA: In Chicago?

JT: No, in California.

BA: Okay.

JT: And there was some weird—it was in a break-off from something from Stanford University. Some sociological place called the Wright Institute. And there was this guy, Art Pearl, I believe his name was, and he developed something called environmental education. But he was a very early thinker, sort of in that Paul Goodman way of the world should be smaller and more integrated and recycled. Anyway, it was interesting.

BA: Who’s Paul Goodman?

JT: He wrote this book, “Growing Up Absurd” which was a famous book in the sixties maybe.

BA: Oh, yeah, gay lib, youth revolt, that sort of stuff—

JT: And an educator, but kind of populist.

BA: And this is like around 1971, ’72.

JT: Yeah.

BA: Wow. So you’ve been writing for –

JT: Millions of years.

BA: Are you familiar with Lucia van der Post, a writer for the “Financial Times” weekend magazine, “How To Spent It”?

JT: No.

BA: Every Saturday they publish a magazine called “How To Spend It” for their upscale–

JT: Yeah, I’ve seen it.

BA: Last month in the weekend magazine she wrote: “It used to be the world of rock and roll, the music and its stars that were the true touchstones of the times we live in, reflecting back to us our preoccupations, our passions, our notions of politics, life and living.” She suggested that: “Today art and artists are attracting the fans, the adulation, the attention and the bank balances that were once the terrain of rock stars.” Do you agree with Ms. Van der Post?

JT: It sounds conceivable. I mean, I would say today there’re still rock stars, or maybe it’s more like hip-hop artists that, you know, Jay-Z – making buckets of money and having huge legions of fans and celebrity, and now a lot of, you know, branching out doing fashion and doing—I mean, I think Kanye West even collaborated with Takashi Murakami on a—Murakami did an album cover for them.

BA: Perfect.

JT: I think there’s some relevance to it in terms of artists and making money certainly. You know, someone that you’ve written a lot about Richard Prince would definitely embody that kind of rock star status. So though I don’t think he’s not—he’s much more low-key in terms of being out in the public.

BA: Right.

JT: I think it’s true that artists—some artists that are in the marketplace that make a lot of money—Jeff Koons—they did become these kind of celebrities or famous. I’m sure in their day somebody like Franz Kline or Jackson Pollock—well, not exactly Pollock, he died a bit too soon, but some of those Abstract Expressionist guys started to make a lot of money when Sidney Janis finally started selling their paintings. And then they were kind of wiped out by the Pop artists.

BA: Janis had this one show where he invited– really early—it was 1962 I think— five or six Pop artists in a group show—“The New Realists”—Warhol was in it, so was Lichtenstein, Oldenburg, Rosenquist—

JT: Yeah.

BA: And apparently all the Abstract Expressionists that were on his roster—Rothko, Guston, Gottlieb, Motherwell— just abandoned him in protest. Because the Pop artists were considered a stain on ‘real’ art.

JT: Yeah. Like the plague.

BA: Exactly.

JT: Actually there’s a piece at the Armory show in this gallery—Galerie Thomas—which is from Munich and it’s a Warhol piece, I’ve never seen it before. Small. He might have done thirty of them, but it’s sort of an homage to Sidney Janis.

BA: Oh?

JT: And they’re green and black—basically they’re from snapshots of Janis as a child and then later he was this kind of very small gymnast and he was at the beach—a bathing outfit holding up a woman on his shoulders. And it’s very cool.

BA: There were multiple images?

JT: Yeah. I think he did 30.

BA: Like 8 by 10s or 16 by 20s?

JT: Not even that large. – – .but yeah, I mean, I think it is true, I mean, even today in “The New York Times”, Roberta Smith reviewing the “Skin Fruit” show at the New Museum and talking about how these artists like Murakami—well, not so much Murakami, but Maurizio Cattelan, Jeff Koons, I mean,

BA: It’s the Jeff Koons curated exhibition –

JT: Of the Dakis Joannou collection, this big Greek collector.

BA: The billionaire tycoon.

JT: It’s like going to an elaborate “Last Supper.” in terms of this cornucopia of – – market-driven –- images… pieces. Urs Fischer and all these characters. It’s all the last 20 years.

But, getting back to that about the rock star thing, I suppose it is true. I mean, I suppose there’re even conceivably groupies for certain artists or there’s a kind of clubby atmosphere. And a lot of dealers have made tremendous amounts of money off –

BA: Promoting.

JT: – promoting artists like rock stars. So like Larry Gagosian who’s –

BA: The king.

JT: You know, maybe he’s the Bill Graham—if that’s a name that rings a bell –

BA: That’s perfect –

JT: Of his time.

BA: How does a critic, an art journalist navigate being honest and at the same time not alienating any artists, dealers, collectors or other professionals he doesn’t like?

JT: I don’t think that’s possible or even advisable. I mean, it’s just the way it happens to be. I mean, there’s a big difference between an art journalist and a critic. I mean, a critic—you’re simply stating your views, and they don’t have to be backed up by anything.

BA: A subjective analysis….

JT: An art critic. Yeah. I mean, if you’re a journalist, hypothetically anyway, you’re reporting something, you’re reflecting not just your own views; you’re reflecting other views as well. So if you think—let’s take that New Museum show, for example.. If I was a critic and I was writing about it I would just say what I thought about it and if there was an essay, if there was a publication I’d probably read it beforehand to get a sense of, you know, I’d read what Jeff Koons’ thoughts were about the show and take it from there. But if I was writing about the collection and Dakis Joannou and some of the works, I’d talk about market value and about the implications of the New Museum supporting basically a private collection –- and what that does. And I’d be getting comments from either dealers or artists or other museum people, I’m sure. And so it’s a very different way. Now, you can be heavy-handed as an art journalist because you’re trying to show something and you’ve just kind of cherry-picked quotes that are negative or positive.

BA: Pushing through your agenda.

JT: But then you run into the distinctive problem of what are your motives and then you can get into trouble over that.

You can be sued for libel as an art journalist if it’s published in a magazine, but you can’t really be sued for libel as a critic because the critic is just your opinion.

BA: A critic-al distinction.

JT: Yeah. Exactly. but it’s very difficult to, I mean, if you’re playing—you might as well go into public relations if you’re really trying to not step on anyone’s toes or get someone upset about something because there’s always—what I always like to do is show both sides. Because there’re wrinkles in both –

BA: Right.

JT: – if there’s a controversy or if there’s a lawsuit about the art world, about the art market.

BA: You’re mirroring how the cognoscenti and the general public are responding to the work as opposed to your own opinion – – . I love the way you dealt with the critic versus the journalist. Now, how do you see yourself? I read your bio and you’ve been a critic –

JT: Yeah.

BA: – a curator.

JT: Right. Yeah.

BA: You’re obviously a journalist, an art journalist.

JT: Yeah. I’m more of a journalist. I mean, in terms of I’ve never really seriously considered myself an art critic. I would have been more in the sense of a reviewer. Like my first—I never had a kind of killer instinct for walking into a show and saying . I don’t like this work and therefore I want to –

BA: [Interposing] Crush it.

JT: – or tear it apart or something. I would just, more than likely, bypass it and write about something that I liked. That would just make more sense.

BA: By writing about something or not writing about something you’re pointing; your addressing what you think is valid –

JT: Yeah, in a way, but, you know, going back to ancient history there was a guy in New York—he was a publisher of something called “Art/World”, his name is Bruce Duff Hooten. And he had a little office in this hotel on the Upper East Side, the Hotel Wales. And he put out this amazing paper of just tons of reviews. It was a tabloid style paper. An old, pre-computer—like in the seventies and eighties. And he was a former art critic for one of the major dailies when there was more than one major daily, like the “Herald Tribune” he wrote for.

But he was kind of—not getting into personal history for him, he was like a reformed drunk basically. And there were a lot of guys that would come there that were sort of in the same boat. But there was a tremendous amount of coverage of shows. And he would just write these short reviews. And the idea is you would go in, you’d see the show, you’d write about it, it would come out, and it wouldn’t be like two months later, say, like reviews come out in “Art In America” –

BA: It’s still fresh.

JT: And I’ve always liked that aspect, both in terms of the news and both in terms of, you know, to sort of be part of some kind of—not dialogue exactly because these are such small audiences typically.

BA: Are you familiar with the writer James Panero from “The New Criterion”? He recently quoted Leo Steinberg’s prophetic observation about the art world from 1968: “We shall have mutual funds based on securities in the form of pictures held in bank vaults.”

When did the point of sale rather than the point of creation come to take precedence to determining the primary meaning for certain works of art?

JT: Oy. What a—oh, so intellectual. I didn’t even—was that Leo Steinberg? Is that who he’s quoting?

BA: Yes. the American art critic and art historian. He’s up there with Clement Greenberg and Harold Rosenberg.

JT: Yeah. I had no clue actually. I thought Leo Steinberg died in 1905 or something, but anyway I could be confusing him with someone else. I don’t even know how to begin on that question, but –

BA: Maybe the Robert & Ethel Scull auction at Sotheby’s Parke-Bernet is a good place to start..

JT: Yeah. Well no, I’m thinking about, I mean, in terms of commerce, in terms of art, in terms of art as investment which certainly the mutual funds—and I’m sure somebody writing in 1968—I mean, a mutual fund today, when you mentioned mutual fund you sort of grimaced, I think, oh, you’re going to lose money.

BA: Right.

JT: Because of that—the unreliability of stocks going up in an orderly manner every year and blah, blah, blah. So it is true at a—okay, so in one of those Scull sales, because I’m not quite sure, there were—I believe there were three Scull sales. The first one I knew about was the famous 1973 one. Fifty works sold for a total $2.2 million. There’s a black and white documentary by E. J. Vaughn that was done on that auction only at—I went to see once years ago at the Museum of Modern Art—and there’s a scene in it where Robert Rauschenberg confronts Scull for selling a work he purchased for $900 that went for $85,000 at the auction—and punches him in the stomach.

BA: Wow.

JT: I mean, it almost seems like I could be imagining that I saw it on film, but this was part of the film.

But basically values started going up in multiples, I suppose, like that auction where they didn’t even print estimates in those catalogs, it was like a separate sheet. There was very little information about what something was or, you know, pre-Artnet, pre-anything. And I was talking recently with—not to namedrop, but with Bill Acquavella who’s doing a show next month that Judith Goldman’s curating from the Scull collection. It’s sort of big hits and bringing them from museums and things.

BA: Oh, great.

JT: Acquavella must be in his seventies now. He recalled bidding unsuccessfully in that first Scull sale, or one of those Scull sales on Willem de Kooning’s “Police Gazette”, which is a major picture. And he said that the estimate was something like $40,000 to $60,000 and it sold for–like a $104 thousand. Like something way over his—but then he tracked the history of it and he later bought it for $2.4 million. He sold it to Steve Wynn for $12 million. Steve Wynn sold it—you know, I mean, it just kept until it became this $60 million picture.

BA: Iconic works are fought over. Is it still privately owned?

JT: Yes. I think Steve Cohen owns it, and I think Cohen bought it from Geffen.

BA: Steven A. Cohen, the hedge fund billionaire—he bought the 40 by 40 inch “Turquoise Marilyn” from Chicago collector Stefan Edlis for $80 million.

JT: Yeah. He also bought Willem de Kooning’s “Woman 111” from Geffen for roughly $135 million. But anyway, the notion of the marketplace is interesting. The only difference is that the—and I think it’s a major difference—that that moment of creation and however it’s determined to be a great work of art or not, it’s still that work of art no matter what happens to it. But in the marketplace it can be the most expensive work of art, a worthless work of art, like in one decade, or from another.

One of the most illuminating kind of accidents that I had in terms of the art—learning about things like that—was in L.A. years ago just kind of wandering around, and there was a used book shop and on the sidewalk there were tons of these old art magazines and I bought a bunch of them. It was like “Arts” magazines from the fifties and the sixties.

BA: Oh, how cool.

JT: I used to always go through them and I would be amazed seeing these big ads for artists whose names I didn’t recognize. And looking at the reviews—and certain names, of course, you—because, you know, Frank Stella is Frank Stella.

But there are many, many, many artists that had—as Andy Warhol would say—their 15 minutes of fame, but they’ve just been whatever, you know.

BA: Good point.

JT: Yeah. By either their own, you know, decisions or other decisions. But anyway yeah, that’s an interesting question. I mean, to pose that. But in 1968 I don’t think a contemporary work of art had sold for $1 million.

BA: I think Johns was the most expensive contemporary artist at that time, and he was commanding, I think, in the low six figures –

JT: Right. Well, just one more example.

BA: Sure.

JT: From Scull, talking about Scull, last November in New York when “200 One Dollar Bills” sold—Andy Warhol’s painting for $40,000,000 something –

BA: $43.8 million.

JT: Yeah, something like that. His seller bought time at auction at the Scull estate auction in 1986 for what was then a record $385,000.

BA: Wow.

JT: And she held onto it for 23 years—that’s like Warren Buffet—buy and hold.

BA: Absolutely.

JT: But I wouldn’t, I mean, I don’t think art will ever be—they argue—they, being people that are trying to sell these art funds, that art is a separate asset class, which is the kind of financial lingo as in stock. So if you have $10 million you want to invest 10% of your portfolio in art. So, you could an have art fund. That I think is, you know, ludicrous. Because I don’t think it’s—first of all, art’s not liquid. You have all these hedge fund guys that lost their jobs and they were buying, you know, George Condo, not to put anything down about George Condo, but—or, you know, Richard Prince or you name it. Murakami. They can’t flip it tomorrow. You know, it’s illiquid.

BA: Right. They can’t—unless they have a rare, fresh to market, iconic work with impeccable provenance.

JT: Yes.

BA: In 2006, Tobias Meyer, the worldwide head of contemporary art Sotheby’s infamously remarked: “… that the best art is the most expensive because the market is so smart.”

Was Meyer telling the truth?

JT: I have to hand it to Tobias for being a great showman and almost like a huckster in terms of the art market. I mean, he is great. He comes up with these great sound bites. But I think that is just a complete crock— because you can’t say that. For example, the Francis Bacon triptych that sold at Sotheby’s for $86 million three years ago that this Russian oligarch, Roman Abramovich bought—that is not a great work of art. That is one of the most overpriced pieces of, you know, failed—I mean Bacon is a great artist. One of the—I think he’s one of the greatest artists of the 20th century, you know, and post-war, whatever. But there are so many examples you could start picking to say Tobias, that’s really pathetic. I mean, I think he has a point in that I think the market is smart or the people that follow the market, but if we wanted to look at “Walking Man 1” by Alberto Giacometti that sold as the most expensive work of art ever at auction –

BA: $104.3 million.

JT: Uh-huh. That sold in London a couple of weeks ago at Sotheby’s. And the – – was something like—I think the estimate was 12 to 18 million pounds or whatever. One hundred million is an insane price. It’s a great work of art, but first of all, it’s a multiple, it’s a bronze. There’re nine others. I mean, it’s an edition of six plus, I think, four artist proofs or something. Anyway, I think that’s just part of the spin that you try to—you know, like oh, that’s brilliant.

There’s this Christie’s auctioneer who I really get a big kick out of in London—Jussi Pylkkanen I think he’s Finnish maybe. Anyway, he’s very smooth with a posh British accent, whatever. But whenever he sells—and if you look at auctions a lot you can tell—against the reserve, in other words, there was really just one real bid in the room –and typically it’s on a telephone.

BA: O.K.

JT: He would always say to the anonymous phone bidder brilliant. You know, like complimenting the person who just bought the farm, so to speak. That no one else was bidding on it, no one else wanted the work. So I think it is true that collectors that seem to be savvy, they know prices, this and that, or they say okay, there are only ten of these made, or this was made and it was reviewed or it was in a museum show or whatever critic—or it was in this collection and therefore—or it came from the artist’s studio, you can make all of these little kind of arguments for this is why it’s worth ten times what the auction house is estimating it’s going to go for. I think you can get killed in this field if you’re looking at it as a pure investment. I mean, you just get murdered.

BA: Right.

JT: And that’s why I like the name of Damien Hirst’s private collection which is called “Murder Me”. Is Hirst’s abundant serial output essential to his oeuvre and an important aspect of his need to keep enough works in circulation to sustain growing global growth or is it a time bomb waiting to explode?

In other words, prices could kill you—perhaps not literally—but definitely figuratively speaking.

BA: Arthur C. Danto has argued in his new book “Andy Warhol” Yale University Press (2009) that the artist’s “Brillo Box” sculptures from 1964 induced a transformation in art’s philosophy so deep that:

“…it was no longer possible to think of art in the same way.”

Danto felt that the history of art had come to an end. He suggested that the installation of the Brillo shipping cartons stacked in regimented piles had realized its possibilities and there was nothing more to be achieved. Art had now become both post-historical and philosophical.

Would you agree with Danto’s premise? Are we still under the huge shadow of Warhol’s last show of grocery cartons at the Stable Gallery in New York? Or are you of the opinion that the history of art opens up new possibilities all the time?

JT: Well, if I was a philosopher maybe I would be able to come up with something to address what Danto’s saying. I mean, that’s the difference between a critic/philosopher and a journalist. Like I would go out and I would ask, you know, I’d call up different people and say, what do you think of this quote of Arthur Danto’s? But basically, I agree up to the point of that Warhol was definitely, you know, some kind of genius…

BA: [Interposing] Game changer – – .

JT: Yes, game changer. Game changer’s one, but even—and not even saying it in any kind of cynical terms, but yes, he put—actually monotized the Walter Benjamin theories from the thirties about mechanical reproduction—he sort of put them in three dimensions or something like that.

BA: Benjaminianized.

JT: In terms of silk screen.

BA: Right.

JT: Mechanical reproduction. I mean, he really just was sort of a post-modern printer I think, an expression event? I mean, it’s hard to know what can happen next in terms of creativity or new art movements because so much art is being made and so many different people are artists, you know, that have gone to art school or not, released from insane asylums and decide to become outsider artists, I don’t know. But you don’t know what someone else might come up with. I don’t know. It’s anybody’s wild guess.

BA: Some would say that postmodern art is art produced by artists liberated from the burden of history.

JT: Yeah. Yeah. It’s the same argument, I mean, in a way of whenever, you know, “Time” magazine had the question on its cover in 1966; ‘God Is Dead?’, I mean, in terms of sort of it’s the end of the road and there’s nothing else to do.

BA: Right.

JT: Maybe that applies for a certain amount of time—who knows? When I was talking before about, hand-delivering copy to a magazine or from a typewritten page and using White-Out to correct your mistakes or using carbon paper to make a copy of it, it just sounds so ancient backward and so labor-intensive!

BA: [Interposing] But the content is –

JT: – turn the switch off in terms of what possibly can be created or what can come next and I don’t necessarily mean Steve Jobs’ IPAD.

BA: Can you name an artist who you initially liked, but through time and repeated viewings changed your opinion? What about an artist who initially you didn’t like, but subsequently came to adore?

JT: That’s a pretty interesting question. I’m still having issues with George Condo, I have to say. I think his work is really awful. And even though I really try to like it, and some of it’s very funny, and he makes so many different kinds of works, so I suppose when I first saw him maybe 20 years ago—I thought, ‘Egad, what’s this rot?’

BA: He’s 50, 52 – – .

JT: Yeah. But I thought it was very punchy and kind of—I like art that’s either crisp or conceptual or else something very different, that packs a big wallop—someone like Basquiat. I know he’s done some really bad works, but from the first time I ever saw some of his graffiti on the Bowery under the moniker, ‘Samo the art bum’, and later connected it to who he was…it blew me away.

BA: [Interposing] “Samo –”

JT: I mean, I’ve always thought his work was amazing. But I think I’m a sucker for this sort of, that neo-expressionist or wild child edge, although he was never really a wild child.

If there’s an artist whose work I don’t really like, or someone I don’t really go out of my way to see it, it might be someone like Elizabeth Murray. Yet a lot of people and important institutions like MoMA, say her shaped paintings are important, and her contributions, especially as a women artist gaining fame in the 1980s, on a track by herself. And I mean, I don’t even really want to say anything negative because she just recently died and too young at that.

I have to say that Murakami is an artist who when I first saw the work I was very underwhelmed by it. And over time I’ve seen certain works of his that I quite liked. And I like his philosophy about making work, or his whole sort of movie producer, George Lucas ‘Star Wars’ type view of the world.

People say he’s copied Andy Warhol’s studio practice but Lucas was his inspiration. The other thing I like about Murakami is that he doesn’t exactly believe in his fame or fortune being long-lasting. He knows the winds will shift and indeed, they have already.

But, you know, that’s a tough question. Both of those are tough.

BA: Could you name an overrated artist and a couple of underrated artists?

JT: That’s like a loaded question – – . Underrated artists. I think I would go back to older artists in terms of underrated. I know that someone like Paul Jenkins who’s from that second generation abstract expressionism and he has been usually throttled in reviews–but he’s someone that I’ve seen his work—I saw a show of his of works from the sixties and the seventies which I thought was fantastic. So I think he’s better known in Europe, and if he lives long enough, may be rehabilitated here.

I used to think Koons was overrated. Now, I’m not so sure though I think he should stay away from curating. I guess the quintessential example of being overrated is Julian Schnabel—at least as a painter, is pretty well accepted, apart from a small number of great (as in broken plate) paintings..

BA: Do you agree with that?

JT: Yes. I think he made some great paintings in the 1980s. I think he really contributed to that whole Neo-Expressionist dialogue, if that was a dialogue going on then. I think it’s lucky he became a filmmaker. And I think he’s very good at that. I have to say I think Richard Prince is a tad overrated in terms of just market adulation in the same way that I think Maurizio Cattalan is a tad overrated although a brilliant kind of thinker and pundit and kind of pun maker, but a serious artist.

And then there’s Anselm Reyle.

BA: Under, over?

JT: Overrated. But he’s newer to the game so I don’t even know. Where someone like, Mark Grotjahn (Gagosian, etal) I mean, there’s a whole scene of artists that have been hitting the market and a lot of my viewpoints on individual artists is colored by the marketplace. Like Andreas Gursky. I think if it’s possible for someone like him to be underrated, I think he’s really pretty great. “99 Cent” store and his recent work in North Korea…

BA: After Richard’s Cowboy.

JT: Right.