Benny Andrews, Janitors at Rest, 1957, oil and collage on canvas, 50 x 35 inches,

In searching for the roots of Benny Andrews mature work, one place to begin is at The Art Institute of Chicago’s art school back in 1957. It was a decade or so before it became common-place for art students to seek degrees in painting and sculpture from accredited universities. It was also a tense time with the Cold War, Russia launching Sputnik I and President Eisenhower sending Federal troops to Little Rock, Arkansas to enforce integration at Central High School.

Andrews credits Janitors at Rest from that year as his first mature work, one that incorporated aspects of collage to the canvas surface. The now-frail painting-collage (not a part of this exhibition but exhibited in 1988 at The Studio Museum in Harlem) is important on multiple levels. For the purposes of this exhibition, suffice it to say, Benny Andrews picked a subject he felt was close to home. The small group of black men cleaned up the turpentine spills and other minor disasters wrought by the students at the famous art school. As Andrews tells it, the janitors spent their “spare time” hanging out in the men’s room—located in the museum’s basement-‘talking and sipping whiskey.”

“They were constantly getting up and mopping up our messes:’ recalled Andrews in an interview. “Then they’d go back…and sit!’ Figuring out a way to add metaphorical ammunition to his composition, Andrews collaged bits of crumpled paper towels and toilet tissues (what the artist calls “foreign matter”) to the camas. The central figure site on a stool, blue-sleeved work shirt rolled up to the elbows, poised for the next inevitable disaster. If you didn’t know about Andrews circumstances back then, the composition would evoke comparisons to the English Expressionist painter Francis Bacon.

Focusing on this early image helps in understanding the predicament of a young black roan matriculating in a white school—one in the “frozen” North, no less. He didn’t focus on a nude model, a Cezanne-like still life or any of the au courant art movements erupting in Chicago then, like the “Monster Roster” school and Painters such as Leon Golub. Andrews had to tom to these real black men for inspiration.

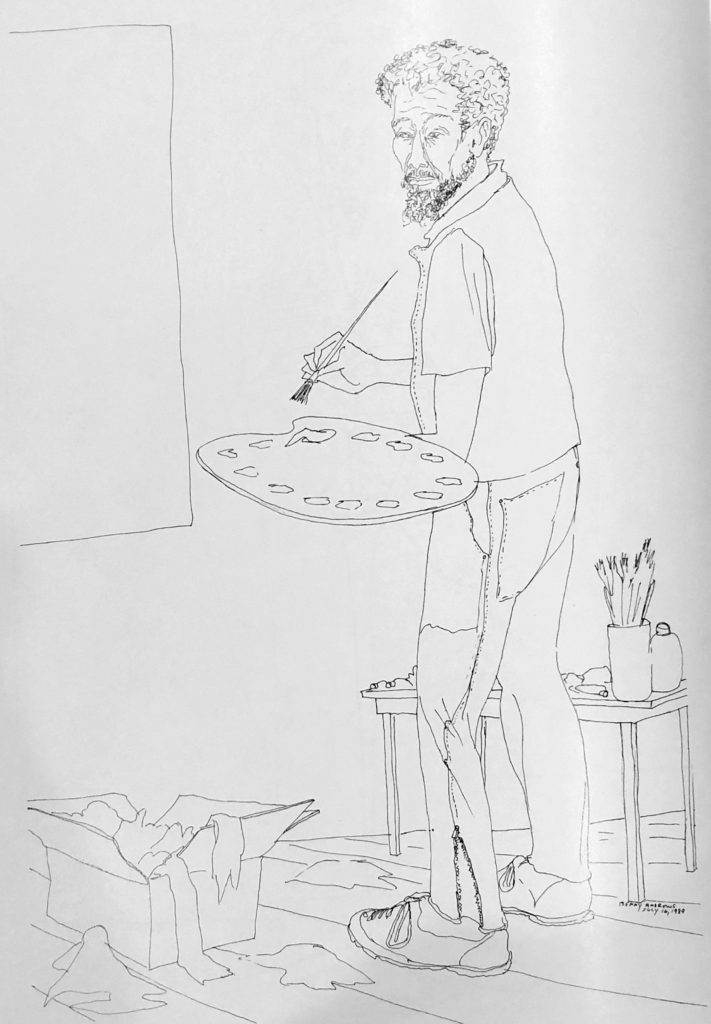

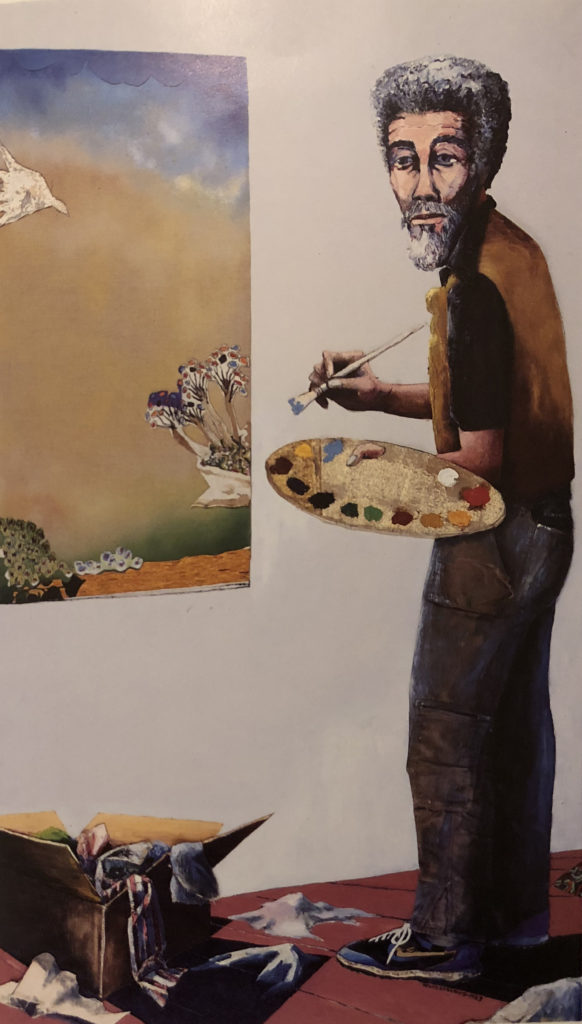

Benny Andrews, Portrait of a Collagist, 1989

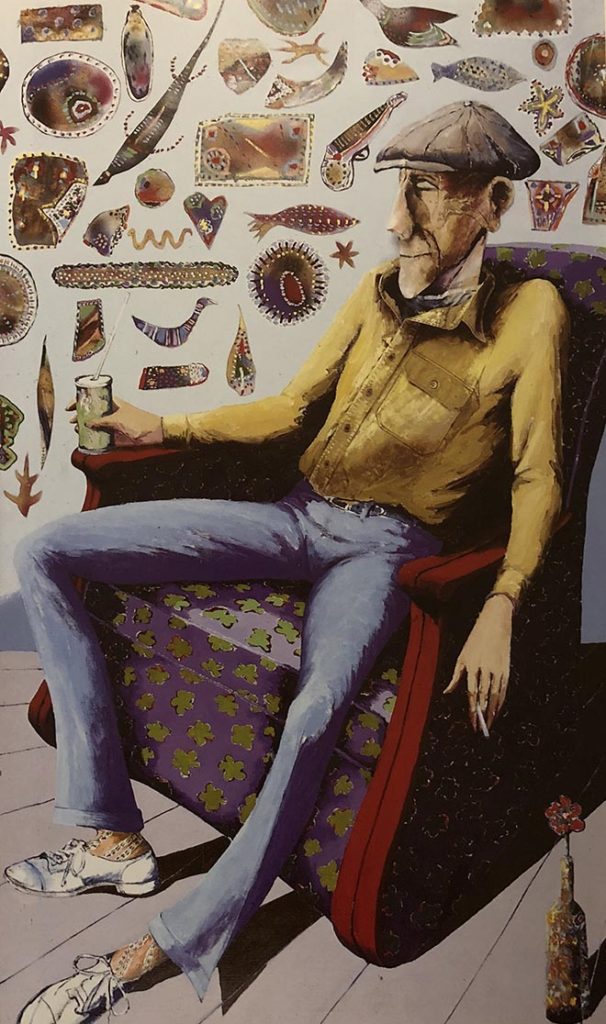

Everything else seemed too far from home. The anecdote about Janitors at Rest leap-frogs to the present and a much larger composition, Portrait of George Andrews, the artist’s father. George Andrews is comfortably seated in a stuffed arm chair, a cigarette dangling from his left hand, a drink gripped in the other. It is an intimate portrait, as textured and evocative as a Vuillard.

With his long legs dominating the foreground, shadows and all, another scene races horizontally along the back wall, a chaotically packed display of George Andrews’ painted creations. By the look in the folk artist’s eye, you can’t really tell if he’s dreaming up those paint-dotted installations of fish, birds and other kinds of natural things or if ifs actually displayed that way on the living room wall. George Andrews is relaxing but his mind is jumping, under the puffy dome of his snap-brimmed cap.

The wood-planked floor, the figure’s patterned socks and pointy shoes, the decorated bottle with the painted artificial flower clinging to the lower edge of the canvas—al of it—pounds a formal battering rain on the metaphorical door marked father and son.

Writing for a recent exhibition at the Madison-Morgan Cultural Center, Benny Andrews described some of that dynamic: “…Ever since I can remember, Dad and I have made do with what we had, and we had about as close to nothing as one could imagine. In fact, I’m sure that’s why I started using collage, and continue to use it, because it allows me to take a seemingly nondescript scrap of fabric and create something artistic.”

Affectionately referring to his father’s nick-name; “The Dot Man” – Benny Andrews wrote: “…He’s like a brush filled with dripping paint willing around looking for some place to place a drop..:’ His quote grows louder as you scrutinize the compelling portrait, imagining the logical progression that led the younger Andrews to collage, a long journey from his boyhood drawings scratched into the ground with a rusty nail. In the 1986 portrait, strips of canvas layered onto the subject’s face season the elder Andrews with a leathery countenance, as if cured by the Georgia sun.

Benny Andrews, Portrait of a Collagist, 1989

While there is no question that George and Benny Andrews soaked in some of the same influences that continue to fertilize their respective palettes, serious observers cannot afford to ignore the larger goldfish bowl of art and artists that made their mark on the impressionable young man from Morgan County in the late 1950s.

Benny Andrews is apt to brush off correlations between his own work and that of the French Cubists who invented the collage form. He even says he was unaware of it as a movement while a student at The Art Institute. There are, however, strong affinities between Andrews and a number of key American modernists and expressionists who also embraced the collage medium.

Arthur Dove’s Goin’ Fishin from 1926 is a powerful pastiche of bamboo, denim and wood. You can feel the tension of the imaginary fishing line and the smooth, bleached out softness of the cut-up work shirt. Dove’s collages from the mid to late 1920s also forged a link with American folk art, but his icons came from the 19th century.

Andrews is passionate about his sources: “I started working in collage because I found…I didn’t want to lose my sense of rawness. Where I am from, the people are very austere. We haw big hands. We have ruddy faces. We wear rough fabrics. We actually used the burlap bagging sacks that seed came in to make our shirts. These are my textures:”

As Andrews developed his collage style, he came to the conclusion: “I didn’t realize it al four but in a sense, Em really constructing—not Paint long my work…I needed something both tactile and tangible.” The dynamic is not always as dear to the viewer, as say a photographic collage by Romare Bearden is. The shards of canvas, patches of cloth or pieces of rope can be almost invisible on a big canvas unless viewed at close range.

A visit to his New York studio makes that subtlety obvious. Parked in a corner, like a heap of kindling, is a stack of rejected canvases waiting for the knife. It is reminiscent of seeing the late painter Lee Krasner at work, tacking up large swatches of her recycled paintings onto a verge swatches spinning them around until she caught the right effect. A veteran of the New York School that championed Abstract Expressionism—one critic dubbed her the “Mother Courage” of the movement—Krasner shared with Andrews the belief and practice in the magical properties of collage. Part of that sensibility—so active in the 1940s-1950s-rubbed off on Andrews once he landed in New York.

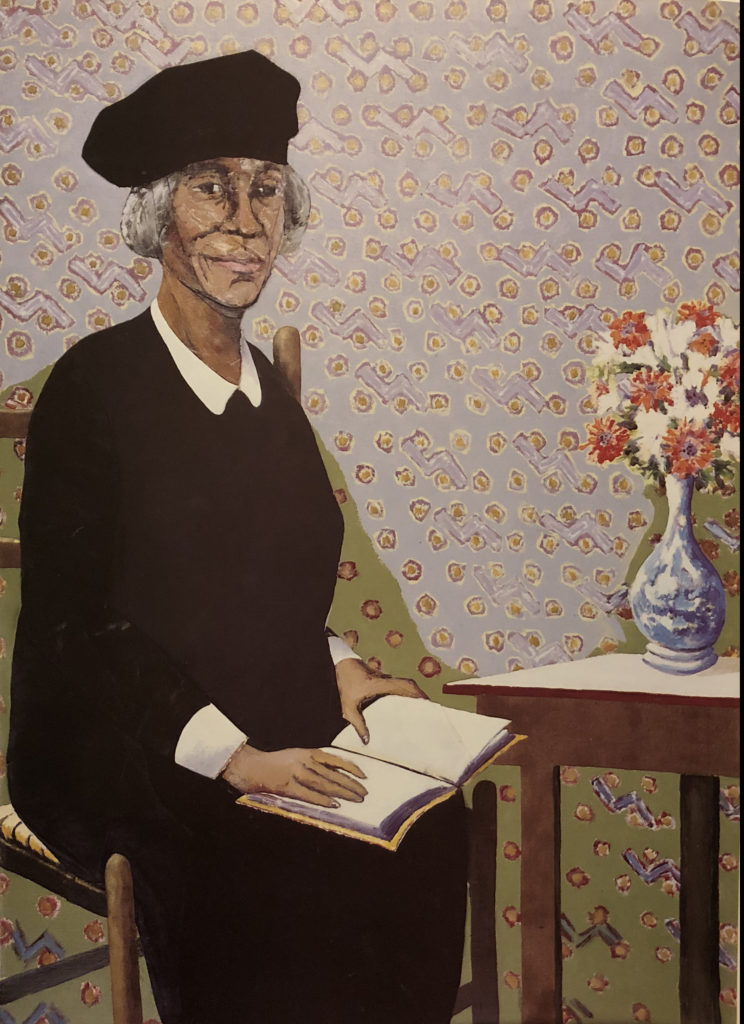

The psychic tug-of-war between Andrews familial roots and the wider world outside of Madison never ceased. Taken simplistically with Andrews, that’s a fatal stance—the artist left home, went North, got an education, got famous and forgot what he was all about. The folk-influenced part is just a distracting aberration. But that exaggerated story line of You Cant Go Home Again crumples in the presence of Portrait of Viola Andrews, executed in 1986.

Simultaneously serene and severe, the obviously devout matron, depicted in Whistlerian shades of black and white, clasps a Bible in bet lap. You can tell by the familiar way she holds the book that she can recite the verses by heart.

A bright scatter-shot of natural light illuminates the space around her, giving the composition an airy feel, uncluttered, crisp and clean. The posture of the artist’s mother compared to the lanky sprawl of the father—in life as well as in his seated portrait—is a marvelous device for showing how opposites attract.

While the composition appears to be carefully posed and one would assume Viola Andrews sat in that straight-backed chair modelling for umpteen hours, nothing could be further from the truth. Andrews is closer to the aesthetic of Edouard Vuillard. who relied upon his imagination —as opposed to models—”to designate the thing I have in mind:’ Even though the portrait is a likeness of his mother, it is more a projection of a staunchly Christian person, inextricably involved with an “easy-going and sinful” man.

Benny Andrews, Portrait of a Viola Andrews, 1986

As in Whistler’s famous portrait of his mother, abstractly titled Arrangement in Grey and Black No. 1, an abstract current runs through Andrews work with just as much juice as the narrative pull of the stern woman sitting alone with her Bible. The image becomes another American Gothic, an icon to stare at and wonder about. (This reference to Grant Wood’s painting shouldn’t be confused with another work by Benny Andrews, titled American Gothic, executed in 1971, the year the Supreme Court upheld the publication of the Pentagon Papers. Far removed from the serenity and safety of Viola Andrews life, the earlier picture is one of the fiercest anti-war statements produced in that or any period.)

But it is the formal quality of the composition that triggers its hypnotic effect. The black dress and medieval-like hat are offset by the starched white curves of cuffs and collar. The painted, all-over patterned wallpaper sets a manic tone to the disciplined stillness of the sitter. A plain wood table and decorated vase of sunflowers separate Viola Andrews from the frantic visual traffic on the wall—dancing to its own boogie-woogie.

Benny Andrews calls his process a “continuous digestion of things:’ Conventions are tossed aside: “It’s almost like being in a sandbox. While you’re standing, it’s much more of a conscious effort, but on the floor, I see more easily. I can visualize images on white paper. My hand becomes an instrument. It just flows through!’ His associations with childhood games or drawing any of the hundreds of heroes and good Buys of his youth and tacking them on the bare wood-planked walls of his world. remain the critical ingredient in his ever-expanding oeuvre. In trying to explain las “eclectic” process, Andrews brought up his novel-writing brother, Raymond Andre. (whose first novel, Appalachee Red, published in 1978, won the James Baldwin Prize for fiction): “He writes a story the same way I draw. Nobody taught us. It’s not pre-conceived. That’s why my work is so hard to define.”

Parenthetically, Raymond Andrews dedicated that first novel “to all of those who ever picked a boll of cotton, pulled a peach, or gone to town on a Saturday afternoon.” That quote embraces much of the childhood activity of the brothers. Without knowing about the tremendous influence of his father “making up and doing things,” one would automatically think Andrews was shaped by Jackson Pollock, the seminal artist who did away with easels and conventional modes of art-making. While it is partially correct to include Pollock in Benny Andrews multi-storied pantheon, the more poignant source and magnet for his art-making is George Andrews.

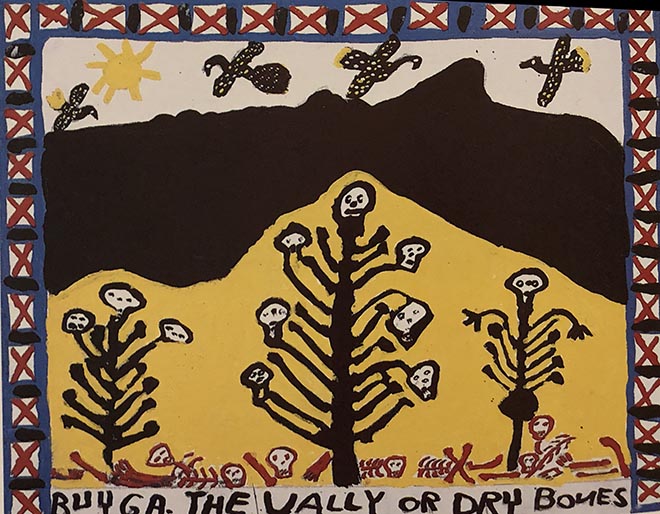

George Andrews, Valley of the Dry Bones

Without suffering the psychic pains of being the offspring “of a famous artist” (read Jimmy Ernst’s autobiography, A Not So Still Lift), Benny Andrews reaped all the pluses. He remained far removed from the “popular culture” of the North except for some magazine subscriptions and weekly “Wild West” infusions at the local cinema. It is important to acknowledge these folkway mots that playback now in an almost magical form, uniting father and son in an exhibition.

In 1988, a widely traveled exhibition, An American Vision—Three Generations of Wyeth Art, closed at the Brandywine River Museum in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, the “home seat” of the Wyeth family. As fathers and sons go, the Wyeths (including the late N.C. as well as Andrew and Jamie) are probably the most famous American artist family outside of the Philadelphia Peales. It is interesting to compare for a brief moment the very traditional and definitely “Yankee” image of the Wyeths to the category-defying traits of George and Benny Andrews.

Benny Andrews, Portrait of George Andrews, 1986

If George Andrews had “studied” painting or art-making as opposed to receiving his multi-media vision through dreams, the dynamic for Benny Andrews would have been significantly altered. Looking back in art history, it could have been a recasting of two “Old Masters,” Pieter Bruegel the Elder and his son, Pieter Bruegel the Younger. The Younger made a handsome career out of copying masterpieces of his more illustrious father. But in the Andrews household the only models came from torn-out pages of Life or Collier’s. It would take years for the family—let alone, outsiders—to recognize that the insatiable object-making and “decorating” by George Andrews tapped a potent vein of folk art.

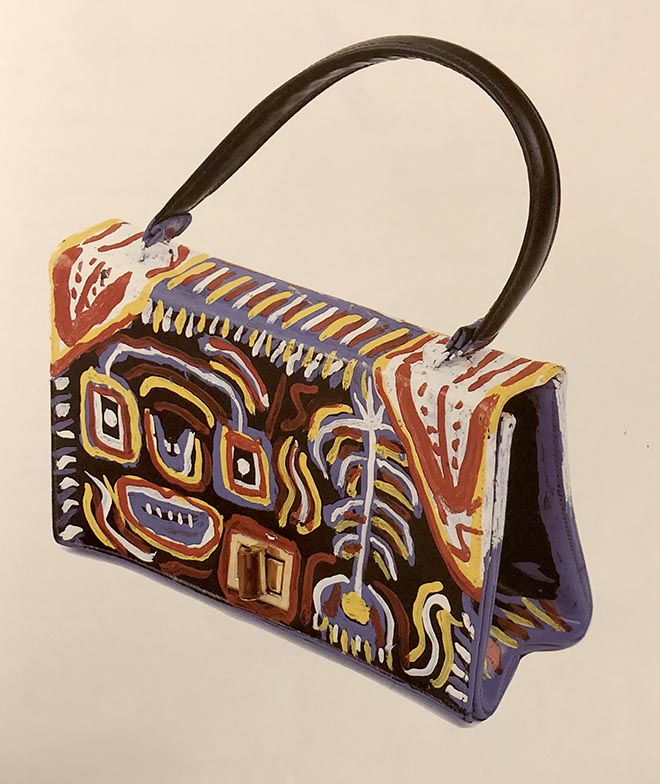

George Andrews, Painted Handbag

Portrait of a Collagist reveals Benny Andrews at work, oval palette in hand, staring intently—not at the viewer—but the studio mirror. In his stretched out, mannerist style, the image comes to us tall and narrow, with the artist flush against the right side of the can-vas, backed op—so to speak—against the wall. Within this narrow space of 50 inches, Andrews struts his stuff, from the cardboard box of odds and ends on the floor to the work-in-progress landscape on the white studio wall

The rectangle forming the landscape on the wall jousts geometrically with the oval-shaped palette impaled on the painter’s thumb. The two disparate shapes seem magnetically attracted to one another. The artist stands with his paint_ brush hovering in the depths space. Despite the stillness of the pose, a kinetic wind blows across the canvas, leaving the sensation that the fabrics and things in the open carton will vault out and up into the painting. Cropped shadows—they have nowhere else to go—tail the figure and the box.

George Andrews, Untitled

The otherwise bare studio wall outlines and magnifies the major elements, acting as the untouched white “negative space” of watercolor paper. With a compulsion to document the tin, Andrews models his casual uniform of safari chinos (the left pant leg is collaged with zippered pockets) and vest, as well as a state-of-the-art pair of running shoes.

In marvelous contrast, This Is George Andrews Boy Ha Ha Ha by George Andrews, jitter-bugs in an ambiguous space, barely contained by the canvas. In a now already famous anecdote—well-worth repeating Benny Andrews outlined the figure of his father on the bare canvas and then George Andrews went to work.

At an uncharacteristically large scale (50 x 44 inches), the painting takes on a breathless narrative with Andrews’ signature whirligig and floral whatnot shapes spinning and sputtering in mass elation. A “picture-caption” located near the bottom right of the canvas spells out in a jangly script, This Is George Andrews Boy Ha Ha Ha and sort of runs out of room there.

In the Southland Series, Benny Andrews pursues the common, intertwined threads of good and evil. Just as his portraits of his parents vividly contrast their wildly different personalities, that same tension of opposing forces persists in his cast of workers and farmers, banters, cowboys, and no-goods.

As Raymond Andrews wrote in a catalogue essay for his brother’s exhibition in 1984, Icons and Images in the Work of Benny Andrews: “Momma was the community’s number one Christian, under the same roof with her lived one of the community’s longest surviving sinners, Daddy:”

This biographical thread weaves into the art of Benny Andrews with Raymond’s even more extraordinary observation: “Momma always prayed that Benny would grow up to be a do artist rather than a ‘pouring’ artist, another of his, the ability from age five to pour water interchangeably from bottle to bottle without spilling a drop, the mark of a moonshiner. This, Momma claimed, Benny got from Daddy’s side of the family where it was said stretched a long line of perfect pourers.”

In the mural-sized Pool, the viewer immediately assumes that the trio of sinful protagonists—so eagerly crouched over the scattered assembly of striped and solid-colored balls—prefer the green felt of a billiard table to the distant terrain of a farmer’s field or the hard bench of a pew.

Hugging the opposite end of the table, the other two opponents (engaged in a game called “cutthroat”) study the risky shot, their red and blue cue sticks held like bayonets. They’re wearing hats too, as different in shape and tilt as their postures. This classic game—no matter what the stakes—is being played in deadly earnest.

The choreography of the players movements is electric, with the center figure in the red-striped pants forming the highest point of the assembled triad. He cups his chin and assesses the chances of his opponents shot. To the right, the third player is crouched further down, to afford a better line of sight, as a referee would in a wrestling match, to detect whose shoulder touches the mat first. He would be the first to yell “scratch.”

Apart from the formal fireworks, the image is severely cropped so all horizontal movement is exaggerated, and every ounce of visual space is keyed to the green baize-topped pool table. On another level, the artist tells a tale with considerable “English” (the phrase for making the billiard ball spin in different directions). Similar in spirit to Local Hangout (painted in the same year) and Boots, Pool captures the thrill of gambling and low-key vice, made all the more comforting by the familiar smoky ambience of the neighborhood parlor. In his unique and strangely surreal way, Andrews leaves the background of the composition alone and white, unlike, for example, a Red Grooms work that would gridlock the walls with signs and at least one window affording additional views. Just when you’re about to pigeonhole Andrews as an Expressionist. you realize he’s a Minimalist too. This becomes especially clear after viewing his spare line drawings—as evocative as Alexander Calder wire-drawn portraits. They tell his life story.

Grooms and Andrews are related geographically and share expressionist/sharpshooter skills in draughtsmanship, Back in the late 1950s, as he found his bearings on New York’s Lower East Side, Andrews met Grooms and his wife at the time, Mimi Grooms, as well as fellow-black painter Bob Thompson (whose career and life were tragically cut short), Jay Milder, and Lester Johnson.

Though plugged into those mean streets in a no-man’s land time between Abstract Expressionism and Pop Art, Andrews never abandoned, and in fact, thrived on, his rural-folkway beginnings and roughly textured figuration. Referring to Andrews fabric-streaked paintings, painter Alice Neel described them as “…a surreal reality evoking not only the history of the person but also of life itself.”

While Grooms found his way to “happenings” and documenting the wilds of Canal Street, Andrews resisted aesthetic assimilation. Returning to the painterly realm of good versus evil or at least, some place in between, The English Teacher stands alone, her book in one hand, a piece of white chalk painted in the other (Color plate 4, p. 36). It’s a black woman at the head of a class we can’t otherwise see. We are afforded an excellent view of the green and black checkerboard floor, made all the more vivid by her pointy red high heel shoes scuffing the foreground. With her floral print skirt, white blouse and vest, the teacher is decked out jaunty and proper.

The blackboard behind her is bare, without even a smudge of chalk dust. The L-shaped expanse of lilac-colored wall provides an eye-resting tonic for the otherwise hard-edged background. Andrews is giving us a lesson of his own in that the teacher is black, and her language is one that was originally and brutally imposed on her culture from an entirely different context. “Black” English is spoken differently because it is a foreign language, even more so in the rural southland where Andrews received his early and moody episodic schooling.

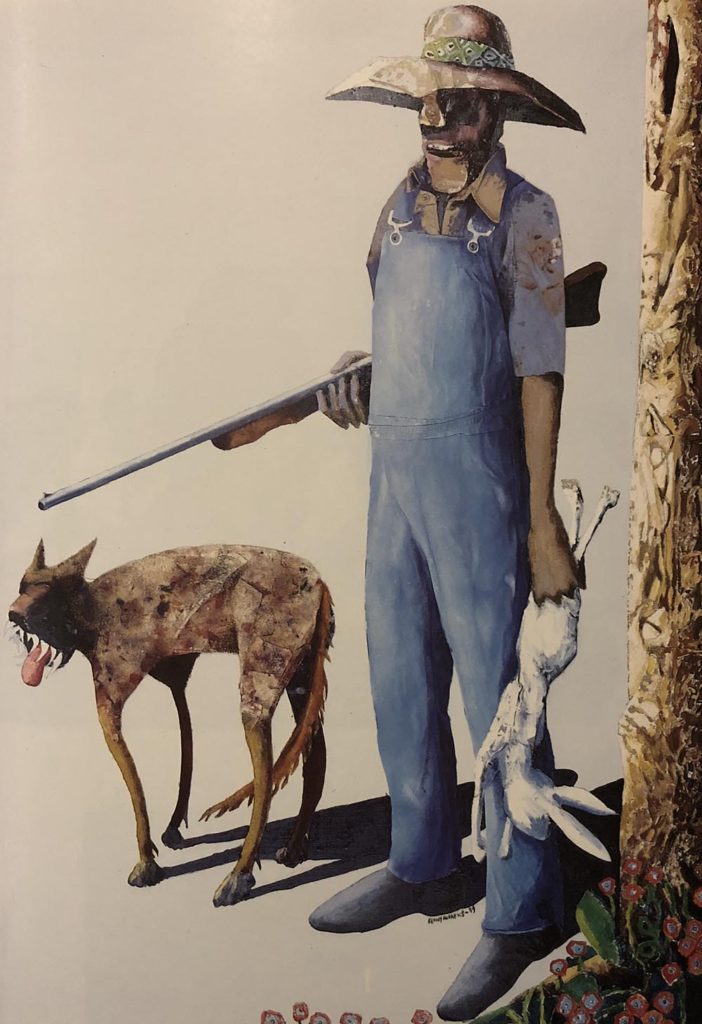

Benny Andrews, The Hunters, 1989

Rounding out the wide-range Rounding out the wide-range of character/ personas in the Southland Series, The Hunters bristles with associations of a hardscrabble land and the folks who somehow survive on it. The plural reference in the title gives equal billing to the hunter in a faded pair of bib overalls and the long-toothed curdog panting proudly at his side.

Cradling a rifle in one arm and gripping the rag-doll legs of the dead white rabbit in his left hand, the hunter sizes the viewer up, as if he too were prey. His wide-brimmed straw hat partially obscures his inscrutable look. The poor rabbit is hanging upside down, looking more like a stuffed animal than a wild one. Not a drop of blood n visible, and no attempt has been made to infuse it with any appearance of a violent end.

Even with the seemingly humorous and picture-taking poses of the predators and prey, a brutal irony leaps out of the frame. The silhouette-black shadows—like the cinematic chiaroscuro in High Noon—are meant to be ominous. It’s a far cry from the mail-order catalog image of a “weekend” hunter decked out in expensive camouflage gear.

Andrews is consistently misconstrued as a realist or regionalist, only concerned with the social-folk ethic of a mostly passed time. In the same way he paints/collages portraits without the subject present, he creates his country land-scapes and Noah-like menagerie of exotic creatures solely from memory or imagination, hundreds of miles away from the red soil of Georgia. While it’s reasonable to say Andrews shares certain historical affinities with social realists like Philip Evergood and the cosmopolitan regionalist Thomas Hart Benton, any label treads on thin ice.

Benny Andrews’ potion for stimulating his unconscious—the place where his art springs, from—”is to be surrounded by things that trigger associations.” That elusive requirement is as strong as was OKeeffe’s concrete need to be close to her beloved hills of Abiquiu, New Mexico or Reginald Marsh’s obsession with the assorted flesh of Coney Island.

Standing before a room sized installation of George Andrews’ art—the only way to fully experience it—you begin to hear the dialogue between father and son. Both are inexplicably unique; yet, somehow each amplifies and crystalizes the other’s voice and vision.

Though he wasn’t a part of the ground-breaking exhibition organized in 1982 by Jane Livingston and John Beardsley of The Corcoran Gallery of Art, Black Folk Art in America 1930. 1980, George Andrews fits seamlessly into Livingston’s cogent definition: “The artists working in this esthetic territory are generally untutored yet masterfully adept, displaying a grasp of formal issues so consistent and so formidable that it can be neither unselfconscious nor accidentally achieved.”

Livingston’s remarkable comment that art requires unbidden miracles to assist in its realization” further bonds the two men into an art historical place recently discovered but still remote. With open passage to his dream-conjured art, George Andrews felt no need to leave home. But throughout his globe-trotting life, Benny Andrews has maintained a lifeline to Madison, spending part of each year living and making art in his nearby studio. It is difficult to imagine hi potent collage form existing without the folk and fabric of Morgan County, Georgia.