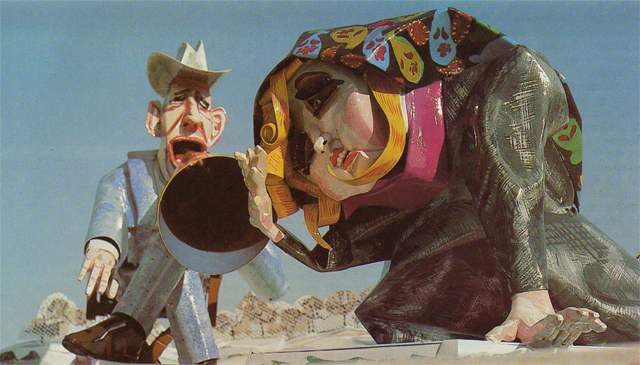

Red Grooms’s Monument to D.W. Griffith

photo credit: Howard Storm

At the New York premiere of Way Down East on September 3, 1920, the audience paid an astronomical ten dollars a ticket to see Lillian Gish swept downriver on an ice floe. Five decades later, New York artist Red Grooms has taken that scene from the D.W Griffith classic, cast it in aluminum, spray painted it in acrylic enamel, and set it down in the middle of Northern Kentucky University in Highland Heights. It is the first monument to Griffith, who was born, reared, and buried on Kentucky soil.

The larger-than-life sculpture is a culmination of Grooms’s lifelong love affair with the movies. An accomplished film maker himself who has cranked out 16mm master-

pieces since 1961, Grooms has already immortalized a host of cinema stars from Gloria Swanson to Charles Boyer, casting them in scintillating dioramas and cut-and-folded paper sculptures. He was ripe for tackling Griffith and company.

By early spring of 1976 Grooms had finished his sculptural “novel” Ruckus Manhattan—a mammoth multi-media portrait of New York City from the Statue of Liberty at the aquatic foot of Wall Street to a furry pimpmobile on the cusp of Times Square. Covering 11,000 square feet of Marlborough Gallery’s- pristine floor space, Ruckus Manhattan attracted over 100,000 Ruckus-hungry customers in a turnstyle-mad three months. The mobs

that boarded Grooms’s thirty-six-foot-long subway car swayed in syncopated abandon with the sculpted passengers that squeezed the perimeters of plaster benches. Heavy duty truck springs kept the car hopping. Fleeing from that fatiguing triumph,

Grooms hit the boulevards of Paris for six months in the fall of that year to ponder his next venture. He had been asked to do the commission in Kentucky, but the klieg light of D.W had not popped in his head yet. Griffith’s spiritual mentor, George Melies, the great French film maker, haunted Grooms in Paris. Another revolutionary in the awkward silence of celluloid, Melies had been an inspiration to numerous Ruckus productions Returning to Manhattan, Grooms had images of hand cranked cameras and swirling ice floes dancing in his view finder.

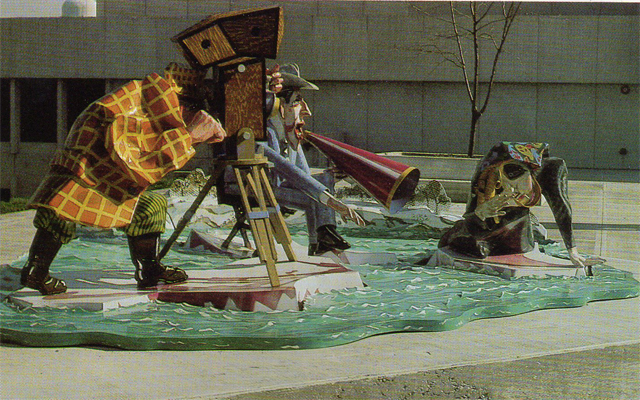

“Way Down East” installed at Northern Kentucky University. photo credit: Howard Storm

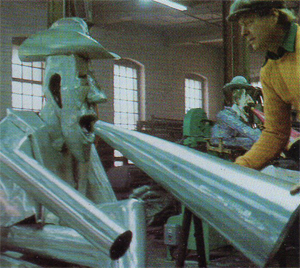

Grooms worked feverishly, translating drawings of D.W , his cameraman, Billy Bitzer, and starlet Lillian Gish into a balsa wood, paper, and water color maquette in

his Chinatown studio. The trio was boxed and shipped to Bob Walcott, a metal fabricator and caster of abstract geometric art in Bennington, Vermont. Walcott swooned over the maquette. Following Grooms’s techniques of paper construction, Walcott carefully enlarged Grooms’s model using molten aluminum in Styrofoam casts and

argon “wire feed” welding. It was his first venture with figurative art.

White River Junction is north of Bennington, Vermont, and the home of the famous ice fioe of Way Down East. In the dead of winter, 1919, Griffith took his film company on location for eight weeks to perfect the sequence that froze movie-

goers to their plush velvet seats Way Down East, a stage play by Lottie Blair

Parker that hit the boards in many a country town in the early 1900s, was just a

frumpy melodrama to most critics, but Griffith bought the rights for an unprece-

dented $165,000, terrifying his lead, Lillian Gish, that the master had lost his marbles.

Red Grooms assembling the aluminum sculpture in Bennington, Vermont. photo credit: Jack Mognaz

Griffith had a great deal riding on the success of Way Down East Three successive box office flops had strained his partnership in United Artists, and the tre-

mendous cost of converting and running the old Flagler mansion in Mamaroneck,

New York, on Long Island Sound (command headquarters for D.W ’s films) was draining his already stretching finances. Griffith desperately needed another success like Birth of a Nation (a film that made cinematic history and tremendous profits

but tarnished his image as a Ku Klux Klan supporter for its portrayal of the post-Civil-War South).

Cameraman Bitzer was in similar straits. Hot on his heels was the talented special

effects man, Hendrik Sartov, whom Griffith hired especially for Way Down East. He resented the encroachment, and the film was Bitzer’s last with the master as

undisputed camera kingpin. (Griffith’s next epic, Orphans of the Storm, was pho-

tographed by Sartov )

The thirteen-reel, three-hour-long epic tear-jerked its way through the cruel exis-

tence of one Anna Moore who is tricked into a mock marriage and a one-day honeymoon in the bridal suite of the Rose Tree Inn by a city slicker (dashin7g Lennox Sanderson who the subtitles proclaim “has three specialties: Ladies, ladies, and ladies”).

Played with lip-curling panache by Lowell Sherman, the playboy abandons Anna

after she becomes pregnant.

The poor waif, ministering to her dying infant in a threadbare hotel room, baptizes

her tot, “Trust Lennox,” in a scene that caused the real father to faint dead away

on the set and soaked acres of twisted handkerchiefs in theaters across America.

Kicked out of her modest hovel by a cruel landlady, Anna starts another pil-

grimage with her earthly belongings packed inside a broken cardboard box.

Alone with her secret, she is welcomed into the baronial but podunk midst of good

Squire Bartlett (“a stern old Puritan” played by Burr McIntosh) only to have the

villain Sanderson materialize again as a dinner guest. A chance meeting at the vil-

lage sewing circle between the spinsterish landlady and Bartlett Village’s gossip,

Martha Perkins (“nobody needs a newspaper when she’s around”) triggers her tongue into conspiratorial ecstasy at a fiddling-crazed barn dance. The morally squeamish squire, fat feet firmly planted on the parquet, points his finger to the door and casts a hysterical Anna to the wind but not before she vents her rage at the chauvinistic fop who is the cause of her misery Pushed by a rampaging blizzard to the river, the exhausted heroine faints on an ice fioe that breaks from the pack and streaks to a rendezvous with the precipitous falls. Hot on her heels, but considerably slowed by an ankle-length racoon coat and heavy boots, is the much-in-love son of the squire played with dashing finesse by Richard Barthelmess. He leaps from one ice cake to another and snatches his love from the jaws of death in the nick of cinematic time.

To capture this scene, D.W perched himself and cameraman Bitzer with the tri-

pod-mounted Pathe crank camera on a makeshift bridge abutting the falls. D.W

had already been injured in the face from a dynamite blast on the river, and several

crew members perished in the frigid-pneumonia-catching environs. Lillian Gish trained for Way Down East with cold baths and walks in winter gales. Attired in a skimpy wool dress, the hearty heroine lay prostrate twenty times a day on the bitter-cold ice floe, one hand and a few strands of her famous ash blond hair immersed in the raging river.

When Red Grooms saw Way Down East during Griffith’s Museum of Modern Art

retrospective in 1965, he remembered the pathetic creature and the stark landscape

of winter By placing Griffith and Bitzer on neighboring ice floes surrounding Lillian Gish—the director armed with a huge megaphone and the cameraman with the snout of the Pathe camera and smoldering Havana cigar—another picture emerged. It wasn’t just melodrama but modern sexual oppression.

During the blizzard scene which Griffith waited three months for, three men had to hold down the legs of the tripod, and a fire underneath it kept the camera’s supply of oil from freezing. Buddies of Dartmouth dropout Richard Barthelmess pelted the exalted director with snowballs but soon beat a hasty retreat from the numbing winds. Lillian Gish was a heartbeat away from death because Barthelmess’s cumbersome costume slowed him down. As crew members screamed from the banks of the Connecticut River in helpless terror, she drifted towards the falls, strands of her hair frozen to the ice. She freed herself just in time to escape death.

During filming, Lillian Gish almost lost her life. With crew members in horror she drifted toward the falls, her hair frozen to the ice flow. Just in time she was lifted free and escaped. photo credit: MOMA Film Still Archives

Lillian Gish said Griffith always wore hats to offset what he thought were too big—a nose and jaw Red Grooms sculpted a splendid Stetson hat for the self-conscious director whose mouth blasts commands to Gish through the gold-tipped, purple-bodied megaphone. From the lip of the concrete skirt that anchors the famous trio to N KU’s plaza you can peer into the wide end of the megaphone and see D.W ’s pink tonsils vibrate impatience. Using the best of Detroit’s automotive paints, Grooms achieved what the experts said was impossible: a brush stroke-look in spray paint over a healthy undercoating of rust-fighting goo. With a two-hour dead-line to work with the viscous paint before the hardeners bent his brush, Grooms used a stick to launch multiple droplets of pigment on the figures. A new wave of punk pointilism swaggered in, providing a cinematic view of raging currents, hard-edged white caps, scraggly trees shaking in the

wind, and vanilla swirls of snow.

David Wark Griffith died in a Hollywood hotel room at the age of seventy-three in 1948 and was buried in the Mount Tabor Church Cemetery midway between Louisville and LaGrange, Kentucky Highland Heights, the site of the sculpture, is a hundred miles away Until the Grooms sculpture was installed on the campus in April of this year, no fitting tribute to the creator of the American art film existed except in a United States postage stamp issued in 1965.

Fueled by a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Kentucky State Assembly, the eight-year-old Northern Kentucky University’s commission has made a big cultural splash in the back yard of Cincinnati, six miles to the north.

The icicles on the eyelashes of the aluminum Anna Moore and the goldilock curls that tumble over her forehead are trademarks in the history of the motion picture. With Bitzer cranking away for dear life on the 1,000-foot reel Pathe camera, flinching

as D.W screams, “Billy, get that face!” Even though the ascerbic wit Robert C. Benchley wrote a review of Way Down East where he voted for letting Anna ride over the falls, Grooms has maintained the lady’s virtue and health and, in the same deft stroke, opened the floodgate for a new look at Griffith.