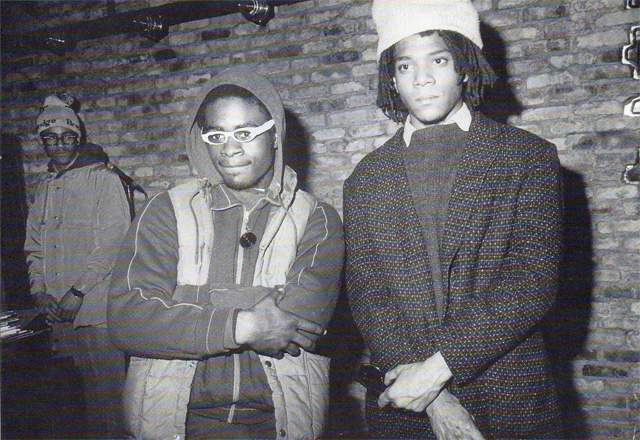

The son of a successful businessman, Basquiat nonetheless cultivated and image of untutored street graffitist. But the streets he strategically chose for his SAMO tag were in Soho and the East Village. Here, Basquiat (right) with a fellow hip-hopper, 1982

As New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art mounts the first Jean-Michel Basquiat retrospective in the United States (opening October 23 and on view through February 14), a flurry of questions surrounds the late artist and his international market:

Was Basquiat America’s greatest black artist, or just a flash in the 1980s art pan?

Can the retrospective recast Basquiat as a historically important painter, more the offspring of postwar European and American art than a flashy graffiti talent?

Is it art world prejudice—or even racism—that keeps Basquiat in the minor leagues with Keith Haring and Kenny Scharf, segregated from such heavy hitters as Cy Twombly, Robert Rauschenberg and Willem de Kooning?

And will Basquiat’s legally entangled and so far cash-needy estate be able to capitalize on his controver-sial legacy? Indeed, Basquiat’s weak art-historical reputation needs revision.

“There’s a misconception about him and the whole body of his work,” says Richard Marshall, the Whitney’s curator of the Basquiat show. “Much of that was Basquiat’s own doing. He represented a lot of things in the ’80s. It all added up to overshadowing the art itself, and I think that should be rectified.”

In August 1988, after a brutal diet of drugs and hurtful reviews, Basquiat succumbed to an overdose at the carriage house in lower Manhattan that he’d been renting from the Andy Warhol estate for $4,000 a month. He was D.O.A. at Cabrini Medical Center. And he was 27 years old. Perhaps not since Egon Schiele has an artist’s early death raised so much controversy and attention. It stands to reason. The former street kid, who had invented a fake religion called SAMO and dreamed of meeting Warhol, had zoomed to rock-star status in a blazing career that began and ended in the ’80s. He kept a suite at the Ritz-Carlton Hotel and acquired a taste for $200 bottles of French wine. Not only did Basquiat collaborate with Warhol on a series of paintings, but they also sold a batch of them to dealer Bruno Bischofberger for $500,000. He owned a $300,000 Picasso still life as well as a $1,000-a-day drug habit. ”

Jean-Michel was almost a fictional creation,” says Diego Cortez, the curator and critic who made early art world connections for Basquiat. Not surprisingly, there seems to be no bottom to the media interest in the artist. As early as 1980, Basquiat was starring in New York Beat, a low-budget, yet-to-be-released film about a black graffiti artist who becomes a painter, made by Glenn O’Brien. (A former columnist for Interview magazine, O’Brien first introduced Basquiat to Warhol.) This year, Shooting Star, a British documentary on the artist’s life

by Geoff Dunlop, premiered on England’s Channel 4. (Because of copyright problems with the estate, however, it is unlikely that the film will even be seen in the U.S.) Two unauthorized biographies (by Phoebe Hoban and Robert Knafo) are being written, and there has been much talk about a planned feature film on Basquiat’s life by painter Julian Schnabel and Michael Holman, a for-mer member of Basquiat’s noise band, Gray. From Hollywood wannabes to SoHo ne’er-do-wells mimicking his painted-text-style, the Basquiat bandwag-on lurches on. “Basquiat attracts parasites, and as long as anybody can make any money on him they will,” says Hoban, a New York magazine writer who’s been working on her biography of the artist for over a year. “It’s a case of art world cannibalism.”

By the last few years of his life, Basquiat’s star had been fading, especially in New York. After two poorly received shows at the Mary Boone Gallery in 1984 and 1985, Basquiat broke with her, only to wind up, in the spring of 1987, with Vrej Baghoomian, a second-string dealer. While most of Basquiat’s market and exhi-bition opportunities had shifted to Europe (especially France) and Japan by 1986, Baghoomian managed to stage two shows at his New York gallery the following year, including a one-night stand of Basquiat’s latest paintings before they were shipped off to separate shows at Galerie Yvon Lambert in Paris and Galerie Hans Mayer in Dusseldorf. During the last year and a half of the artist’s life, according to the formidable Bischofberger, who describes himself as “Basquiat’s lifetime exclu-sive dealer,” Basquiat sold unaccounted numbers of paintings and drawings out of his studio to Baghoomian for cash while receiving funds from Bischofberger and New York’s Galerie Maeght (later Galerie Lelong) for supposed exclusivity. “He didn’t fulfill his promise because he was not in a state anymore to act responsibly,” says Bischofberger.

Only his headline- and myth-making death resur-rected Basquiat’s moribund market. A speculative invest-ment frenzy ensued. In the first posthumous test of his secondary market, for example, an untitled work from 1983 sold at Christie’s New York in November 1988 for $110,000, four times the high estimate. Between May 1989 and November 1990, 29 Basquiats sold for $200,000 or higher at international auctions. Famous Moon King, 1984, led the pack, selling for FF2.9 million ($567,000) at the French auction house Perrin, Royere, Lajeunesse in June 1990, the peak of European speculation in Basquiat. The lure of major money following his death also sparked a fierce and protracted legal battle over who would represent the artist’s estate.

Powerhouse dealers such as Bischofberger, Boone, Annina Nosei, Larry Gagosian and Robert Miller, as well as the relatively obscure Baghoomian, jockeyed for exclusive representa-tion. It was an open field. Unlike his mentor Warhol, who had died in February 1987, or his downtown friend Har-ing, who died in 1990, Basquiat had left no will. (Basquiat generally ignored paperwork and didn’t file or pay any income taxes for the three years prior to his death.) The artist’s Haitian-born father, Gerard, a successful Brook-lyn accountant and businessman, became executor of the estate, even though the two had been estranged for years. Basquiat’s Puerto Rican–born mother, Matilde, divorced from Gerard, was the cobeneficiary. Just days after his son’s death, the senior Basquiat hired Michael Ward Stout, a copyright-law specialist and influential art world figure, to marshal his son’s assets and assist in handling the estate. Besides his collection of antique toys, African art and Gustav Stickley furniture, Basquiat left behind prodigious amounts of his own art, including 917 draw-ings, 25 sketchbooks, 85 prints and 171 paintings. In addition, there were two collaborative paintings with Warhol as well as 20 other Warhol works. There was also one “copy” after Warhol’s Electric Chair in Green. (One of Basquiat’s Warhols, a real Drag Queen silkscreen on canvas, was sold by the estate at Christie’s New York in February 1989 for $176,000.)

Christie’s “date-of-death market value” appraisal for the estate came to $3.2 million. After applying a 70 percent “blockage dis-count” on the paintings and drawings (which takes into account the value of the items as if they were dispatched en masse in a forced estate sale), that estimate shrank to $1.05 mil-lion. As is frequently the case with art-rich estates that employ the blockage discount, those figures—which determine the amount of tax—are sure to be formally reexamined by the IRS and its Art Advisory Panel.

Undeniably, there is a startling gap between the value assessed by Christie’s after the artist’s death and today’s going price for many Basquiats. For example, the 1982 painting Charles the First, appraised at $30,000, currently carries a $500,000 price tag at Robert Miller. But at the time of Basquiat’s death, Christie’s appraisal (including the “blockage discount”) was mostly on the mark, with paintings valued at an average of just under $10,000 each. Bischofberger says he never sold a Basquiat for over $30,000 while the artist was alive (though shortly before his death, Christie’s sold Basquiat’s Water-Worshipper for $35,200). A glar-ing exception: the 1982 Dos Cabezas—inflated by virtue of belonging to the Warhol estate—which, with a $15,000 high estimate, fetched $99,000 at Sotheby’s marathon Warhol sale in May 1988.

There were some very disgruntled dealers in spring 1989 when the Robert Miller Gallery became the Basquiat estate’s exclusive dealer. The 57th Street gallery had never been associated with the artist or his work. But Miller already represented the Robert Mapplethorpe estate and foundation, another of Stout’s clients. (Stout, Salvador Dali’s attorney from 1974 until 1989, also serves as executor of the Mapplethorpe estate and is chairman of the board of the foundation.) So it seemed destined that the Basquiat estate would fall into Miller’s hands.

“I wasn’t a contender,” says Larry Gagosian, who exhibited and sold many early Basquiats to West Coast collectors when the New York dealer was still based in Los Angeles. “I tried to get into it, but I got absolutely nowhere….It became a lawyer’s deal where he [Stout] just kind of pipelined the thing to Miller.” “That’s not true at all,” answers Stout. “It had nothing to do with my ‘pipeline to Miller.’

I’m not Robert Miller’s boy in any way.” (The Miller-Stout alliance has sparked criticism that the Whitney, too, is playing favorites. Curator Marshall, for example, also organized and wrote one of the catalogue texts for the Mapplethorpe exhibition at the museum in 1988. Nonetheless, the Basquiat show may well be Marshall’s swan song at the museum. It has been widely rumored that he, as well as fellow curator Richard Arm-strong, holdovers from the Thomas N. Armstrong regime at the museum, are leaving.)

Locked out from the potential gold mine, Baghoomian went after the estate, Gerard Basquiat and the Miller gallery in New York Surrogate’s Court, charging that he had “the exclusive right” to sell all of Basquiat’s art-work, based on an oral agreement with the artist in June 1988, two months before Basquiat’s death. He sued for $40 million. Using May 1989 auction prices as a guide, Baghoomian estimated the value of Basquiat’s paintings and drawings at a “conservative” $41 million.

Kelly Inman, Basquiat’s live-in “bookkeeper,” also sued in Surrogate’s Court, claiming she had a 50 percent partnership with the artist. Coupled with Baghoomian’s contention that he was entitled to 50 percent of the revenue from all Basquiat sales, the estate faced being shut out altogether.

Baghoomian also claimed in the same court that Gerard Basquiat had orally agreed to abide by the so-called June agreement. The estate, represented in the suit by Stout’s colleague Robert W. Cinque, counter-charged that Baghoomian had “attempted to steal more than 20 works of art” that Basquiat had consigned to him. Baghoomian argued that he bought the paintings outright with cash. Gerard Basquiat vehemently denied Baghoomian’s claim, according to court papers.

The judge slapped a restraining order on the estate and the Miller gallery, forbidding them to sell any works of art. That damaging proviso lasted between May and December 1989, a significant slice of late ’80s art boom. They were only allowed to market Basquiats again just as the art market was starting to hemorrhage. But they had to ask the court’s permission in February 1990 to secure a $500,000 loan from the I.B.J. Schroeder Bank and Trust Company in order to satisfy late-payment penalties to the IRS and “substantial litigation costs which the Estate has incurred and continues to incur.” Miller put up $250,000 in collateral. Baghoomian’s charges were finally dismissed in Surrogate’s Court in August 1991.

According to Stout, the estate has spent “several hundred thousand dollars” in legal fees, most of it on litigation. A still-outstanding Federal District Court suit against the estate charges that three Basquiat paintings allegedly purchased by a private New Jersey collector from the artist in 1984 were never delivered. Mary Boone is the plaintiffs chief witness, one more instance of the tensions existing between Gerard Basquiat and his son’s former dealers. Baghoomian is now presumed to be living abroad (see Art & Auction, May 1992), probably in Armenia. (Baghoomian is an Iranian of Armenian descent.) His gallery was forced into involuntary bankruptcy last April with an outstanding debt of over $1 million. In the May issue of IFARreports, the Art Loss Register lists 61 works from Baghoomian’s inventory, including 17 Basquiats, as “missing objects.” Baghoomian’s flight and subsequent abandonment of libel and copyright suits in other venues have doomed his chances to legally participate in any secondary sales of his former star artist.

“Vrej constantly pounded into Jean-Michel that they were ‘the only two dark people in the art world,” says Nina Conolly, a New York painter who worked for Baghoomian at the time of Basquiat’s last shows. “Because of this, Vrej was the only one Jean-Michel could trust.”

James Van Der Zee’s portrait of Basquiat, 1982. Van Der Zee was the great African-American photographer, known for his portraits of the black writers, artists and musicians of the 1920’s Harlem Renaissance

The layers of courtroom jousting, recurring rumors of fakes entering the market and the difficulty in authen-ticating genuine Basquiats because of feuding between experts and rifts with the father (see box on previous page), rival the drama of the ascent and subsequent decline of the painter’s auction prices. At present, only top-notch Basquiats, the relatively rare ones with undis-puted provenances, have recouped some of their former brio, and they hover in the $150-200,000 range. Last May at Christie’s New York, ISBN, 1985, from the estate of Fredrik Roos (the late Swedish collector/industrialist) sold for $187,000. Nonetheless, the numbers still reflect a steep 50 percent drop from previous levels. Mediocre works—which still abound—have little resale potential in the current climate. With that proviso, a highly placed auction source notes, “People are buying now in antici-pation of the Whitney show.” Not sulprisingly, sellers are lining up for potential windfalls. “The impact of shows like this tends to be felt now in that we are being shown very nice Basquiats by people who would like to see them on the auction block in November,” says Diane Upright, head of Christie’s contemporary department.

A retrospective (unrelated to the Whitney’s) of 75 pictures that closed last month at the Musee Cantini in Marseilles, organized by former Centre Pompidou heavy-weight Bernard Blistene, also primed the European mar-ket pump for Basquiat, whose European following early on eclipsed American interest. “Basquiat’s • awing style appeals to the more sophisticated, ol• -r generation of collectors in Europe,” says Bi o erger. “His work looks very Europearialess sanguine view is offered by Louis Bofferding, a New York art consultant and private dealer who acted as Roos’s agent in the mid-1980s: “For the Italian and French Eurotrash crowd, Basquiat plugged into all of their fantasies.”

Basquiat’s high prices on the auction block and elsewhere do not guarantee him a prime art-historical berth. In many ways, the Whitney show will—for the short term, at least—make or break Basquiat’s reputa-tion. Marshall’s curatorial acumen, backed by a profuse-ly illustrated catalogue, with essays by six prominent critics (to be distributed by Harry N. Abrams), aims for a major reassessment of Basquiat’s oeuvre. Greg Tate probes Basquiat’s iconographic cast of characters—what Tate calls the artist’s “warrior-angels”—”the enshroud-ed and enshrined black saints, dead boxers, jazz musi-cians, freedom fighters.” Tate crowns Basquiat the “pop-ulist postmodernist.” Fellow catalogue essayist Robert Farris Thompson, the Yale art historian, writes that Basquiat “confronts the anatomy of the city at its racial, linguistic, and cultural cutting edges.”

With this new critical thrust also goes the major risk of a dud show, which might well cloud the future of Miller’s investment and the potential riches of the estate. “A tight, tough, not-too-big show would serve him well, as it does most artists, particularly people with short careers,” says Museum of Modern Art Curator Robert Storr. “If the Whitney tries to overblow it, like the Schnabel show, then it will be disastrous.” But with a checklist of about 85 paintings, the Basquiat show will be even bigger than Schnabel’s. The majority of the work is from the early and most productive phase of Basquiat’s career, from 1981 to 1983; only two are from 1988. AT&T is spon-soring the show, with a major grant of $100,000, and Madonna, an old friend from club days and a Basquiat collector, contributed $25,000.

A strongly received U.S. show would establish a crucial beachhead for Basquiat’s post-’80s credibility and offer previously negative critics a window of opportunity for reevaluating Basquiat’s work. It does not, however, help the cam-paign that major venues such as Chica-go’s Museum of Contemporary Art and the Art Institute, the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) in Los Angeles and the Centre Pompidou in Paris all turned down the Whitney’s invitation to travel the retrospective. Additional venues in Germany and Japan are still hoped for. At press time, the lineup of institutions that had accepted included the Menil Collection in Houston, the Des Moines Art Center in Iowa and the Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts in Alabama.

“I, for one, am shocked that more museums in this country like MOCA have not taken the retrospective,” says John Cheim, director of the Robert Miller Gallery. Cheim organized the gallery’s major Basquiat drawings show in Novem-ber 1990. “I thought it would be like the Warhol retrospective, with people jumping for it.”

“It was a joint curatorial decision,” says Dawn Setzer of MOCA’s press office. “The big factor was the closing last April of the Temporary Contemporary [the museum’s interim exhibition space designed by Frank Gehry]. MOCA likes Basquiat’s work. We have three pieces in the collection. We’ve had to turn down a lot of things because of the TC closure.”

In the view of his partisans, the art world’s ill will toward Basquiat goes back a long way. “A lot of critics and artists were waiting for Basquiat to fail,” says Glenn O’Brien. “Jean-Michel’s paranoia, was not entirely unfounded. He felt misunderstood, that he wasn’t given his due because of his age, his lack of formal art training and his race. He hated being characterized as a graffiti artist.”

“He gets singled out for a particular kind of market scrutiny beyond what other artists get,” says Gagosian. “It comes down to a racist thing.”

Other defenders of Basquiat’s artistic legacy hip-hop across the landscape of curators, critics, collectors and popular-culture shakers. “Basquiat took on the old-boy network of master painting in a, very strong way,” says Lowery Sims, associate curator of 20th-century art at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. “In that sense, he really put himself into the fire, because it is always assumed to be the province of white male artists to have the sense of grandeur, the sense of scale.” Sims has arranged for the Metropolitan to hang two giant Basquiat “master” paintings, from his 1985 Palladium nightclub commission, in the museum’s huge sculpture hall during the Whitney run.

“Basquiat had a very sophisticated, synthetic talent—when he was going full tilt, he produced amazing drawings,” says Storr. “When he was doped up, or when other people worked with his stuff, he produced a lot of facsimiles of his own work. That wasn’t so good.” In his intro-duction to Basquiat Drawings (published in 1991 by Bulfinch/Little, Brown), Storr observed: “Desperation is never pretty. It can be stylish, however, and Basquiat understood this completely.”

Some rather fearsome criticism came from Robert Hughes, who dis-missed the artist in a brutal essay for The New Republic in 1988, memorably enti-tled “Requiem for a Featherweight.” Wrote Hughes: “It was a tale of a small untrained talent caught in the buzz saw of art-world promotion, absurdly overrat-ed by dealers, collectors, critics, and, not least, himself….Far from being the Char-lie Parker of SoHo (as his promoters claimed), he became its Jessica Savitch.”

“Hughes represents an aspect of the New York critical community that refus-es to recognize hip-hop culture and its visual manifestation in what Jean-Michel developed as legitimate,” says David Ross, the director of the Whitney. Ross postponed the retrospective for a year when he joined the museum in early 1991 “to make sure the catalogue would reflect serious critical writing from a variety of voices.”

Basquiat, of course, has already been spin-meistered as the “black Jack-son Pollock”—as well as the black Twombly, Dubuffet and de Kooning. “I think one of the terrible phenomena for any black artist is how he or she is co-opted by the community as the black something or other,” says Hilton Als, a writer for the New Yorker and the Village Voice. “Jean-Michel was one of the only true artists of his generation. I don’t think it’s possible for the art community to understand his work because a lot of it is in code, and a lot of it is expressly for colored people, and a lot of it comes out of being colored.” Als compares Basquiat’s work to the incendiary early novels of James Baldwin.

It remains to be seen if the over-whelmingly white art world is ready to admit a black painter such as Basquiat to its pantheon, given his drug-dominat-ed lifestyle and “bad boy” behavior. In 1985 Bruno Bischofberger arranged a Basquiat show through the Swiss ambassador in Abidjan, capital of the Ivory Coast in West Africa. “He wanted to do a show in ‘Black Africa,” recalls Bischofberger, “to see where his sources came from.” Basquiat arrived a day late for the gala opening, but managed to explore the surrounding countryside with the Swiss dealer.

Two years later, at his opening at Galerie Yvon Lambert in Paris, Basquiat met and befriended the Ivory Coast artist Ouattara and planned to make a second African trip. His premature death, which came just as he was moving in a new stylistic direction, leaves in question Andy Warhol’s prediction: “I think he’s going to be the big black painter.”