Roy Lichtenstein on the pier in East Hampton, where he moved in the seventies from his sixties marble-walled loft apartment in the Bowery. photo credit: Sarah Wells

In 1962 Roy Lichtenstein painted a canvas called Masterpiece, in which a ravishing blonde sprung from a True Romance comic coos pre-sciently in a balloon caption: “WHY BRAD DARLING. THIS PAINTING IS A MASTERPIECE! SOON YOU’LL HAVE ALL OF NEW YORK CLAMORING FOR YOUR WORK!” Yet even Lichtenstein’s humorous miniskirted oracle could not have predicted the enormous success—and controversy—that the artist’s so-called pop paintings would spawn over the next two decades. By 1965 he had given up the comic-strip captioned style in favor of a more eclectic vision culled from the history of art. But before the radioactive dust of pop had settled, critics were seriously debating whether Lichtenstein was among the best or the worst artists of the century.

“Roy Lichtenstein 1970-1980” is an exhibition that magnifies the artist’s recent casual comment, “I don’t mean to go through the history of art. It just seems to work out that way.” The ten-year survey just coming down from the walls of the Seattle Art Museum will be unveiled in New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art on September 22. The show will no doubt spark a new round of debate.

The new pictures radiate both pomp (not pop) and power. With nary a cartoon in sight, the show of sculptures and lush canvases unfolds in a suite of still lifes. Silver pitchers, red lobsters, slivers of yellow lemon peel, and plump goldfish pose on table tops or squeeze into crystal bowls. Diagonal stripes of blue and white clash against horizontal lines, pushing the picture plane in a riot of directions, His signature Ben Day dots, recruited in the early 1960s from the commercial printing process, parody their halftone function, teasing in relentless variation the play between light and shadow.

Lichtenstein table-hops from American Indian motifs, suffused with tribal symbolism, to turn-of-the-century Parisian boulevards and the likes of Gris, Leger, Braque, and Picasso. Sandwiched between are slices of Italian futur-ism and architectonic entablatures. A dressing of wry trompe l’oeil collages further accents the visual feast. In close collaboration with Lichtenstein, Jack Cowart, the show’s director and organizer (as well as curator of nineteenth-and twentieth-century art at the Saint Louis Art Museum), sifted through ten years of kaleidoscopic output. Having initially agreed on showing fifty paintings for the international retrospective, artist and curator exchanged lists of favorites, and eventually laid out the chosen canvases on Lichtenstein’s studio floor to fine edit. Elbow to elbow, the two collaborators cast their principals in the spirit of a big-budget Broadway musical, making sure their stars would shine under the klieg lights.

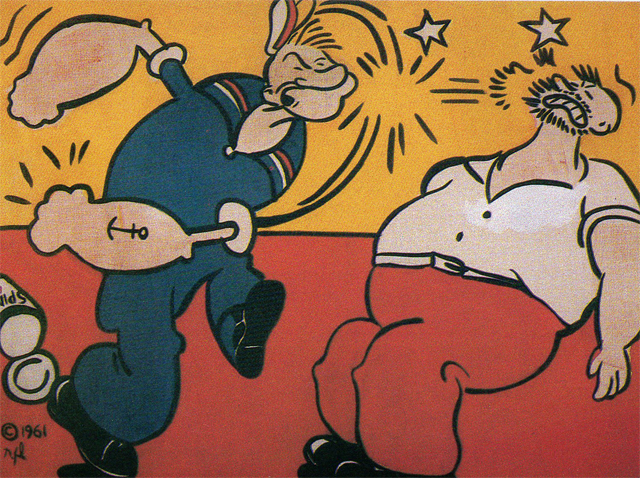

Straight from the comics, Lichtenstein’s Popeye, 1961 oil and magna on canvas, 42 x 46 inches, delivers a pop-art knockout blow to Brutus. photo credit: Leo Castelli Gallery

Crowned the prince of pop during the 1960s, Lichtenstein catapulted onto the wings of a McLuhanized media with his cartoon heroes and blonde beauties from teen-romance maga-zines. While President John Kennedy exuber-antly ordered military advisors to Vietnam, Lichtenstein bombarded the moody and intro-spective art world of abstract expressionism with squeaky-clean, hard-edged pictures. The artist was far more successful with his signature Ben Day dots and bubbled captions than were the M-16s that disappeared in the quagmire of Southeast Asia. But the tempo of those times—”Twisting the Night Away” with Chubby Checker—embraced Lichtenstein and positioned him in the full-color pages of Life magazine with the taunting headline, “Is He the Worst Artist in America?”

Wordsmiths with buttoned-down adjectives had a field day with the painter’s canvases depicting aerosol cans, light switches, rollerskates, step-on garbage cans, and comic-strip blowups of abstract brushstrokes. The big im-ages, flat as pancakes, without a trace of depth, infuriated and bewildered most con-noisseurs of modern art. The red and yellow flames belching out of the belly of Lichten-stein’s cartooned warplanes escalated comic-book vocabulary into pop onomatopoeia. “Whaam,” “Varoom,” “Brattatta,” and “Takka Takka.” The aerial dog fights over unpolluted skies—”OKAY HOT-SHOT, OKAY! I’M POURING!”—poleaxed the ab-stract bandwagon of the Second Generation and brought representational art—of a kind—back into the living room.

Artists, liberated from the brooding couches of analysts’ offices, sprung from the tortured angst that would translate onto huge canvases in spatters and chips, looked outside and saw the sun was shining. It was time to have fun, to exorcise the postwar blue period. So the “New Vulgarians” (a term used for Lichtenstein and company before “pop’ was canonized) arrived on the scene. What Waring blender co-coon could produce in short order the likes of Lichtenstein, Andy Warhol, and James Rosen-quist? Only New York. This trio was painting in the same city with remarkably similar sub-ject matter, yet without having met or even seen a reproduction of each other’s work.

Pow Wow, 1979, oil on canvas, 97 x 120 inches

Though born and bred on Manhattan’s Up-per West Side, Lichtenstein first gravitated to the Midwest, specifically Ohio State University in Columbus. He picked up a bachelor of arts, a master’s in fine arts, a wife, two children, a long string of freelance jobs, and his first one-man show in 1949, at the 1030 Gallery in Cleveland. No stranger to New York galleries, Lichtenstein had four consecutive one-man shows at the John Heller Gallery from 1952 to 1957 The reviews were not earth-shattering, but the noted figurative painter and active art critic, Fairfield Porter, wrote in a 1953 issue of Artnews, “He gets it down in one spontaneous layer and he gets it down right.” The shock waves did not hit until February 1962, with Lichtenstein’s first one-man show of pop pain-tings at Leo CasteIli’s fledgling art emporium. Overnight, Lichtenstein metamorphosed from professor at Douglass College (Rutgers Univer-sity’s sister school) in New Brunswick, New Jersey, to world-class artist.

While Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg—earlier shock troops from the CasteIli stable—were turning the art world topsy-turvy with bronzed Ballantine Ale cans and a mangy-looking billy goat, Lichtenstein delivered super-market colors and comic-book compositions to the museum arena. In 1963 Lichtenstein’s pain-tings and works on paper shuttled from the Ferus Gallery in Los Angeles to Galerie Ileana Sonnabend in Paris before returning to Castelli’s in New York. From 1966 to 1968 his work shattered attendance records at the Cleveland Museum of Art, the Pasadena Art Museum (now the Norton Simon Museum), the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam and—the crowning jewel—the Tate Gallery in London. Never before had a living American artist been shown at the Tate. Never again would one, living or dead, create such a stir.

While the artist’s caravan of images hop-scotched Europe, the home fires were kept burning with two Time magazine covers. The May 24, 1968, issue featured a Ben Day polka-dotted Bobby Kennedy, one of the artist’s rare representations of a “real” person. The June 21 issue had Lichtenstein’s smoking revolver spitting yellow and red curls of destruction for a story on “The Gun in America.” Though the artist brushes aside the sociological and political portent of his work, the near-history-book unfolding of contemporary times that weaves in and out of his sixties canvases merits consideration. As Nigel Gosling declared in the London Observer, Lichtenstein is a “kind of Ingres from Manhattan.”

The artist flirts with depth in Fishbowl II, 1978, painted bronze, 39 x 24 inches, one of a group recent efforts in sculpture

In September 1969, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York mounted a ma-jor survey show of the artist’s work; a fat, coffee-table volume organized and written by the museum’s curator Diane Waldman, sweet-ening the tail end of Lichtenstein’s roaring six-ties. Within a year, Lichtenstein would pack up his easels and leave the marble-walled loft apartment building on the Bowery for the ocean-sprayed main street of Southampton.

Long Island has traditionally been a strong-hold and blue-chip haven for the abstract expressionists (De Kooning still lives and works in the Hamptons and Jackson Pollock is buried in East Hampton’s quaint cemetery). The thought of the pop patrician invading this turf, I thought, heading there for an early-morning interview, seems a delightful heresy Outfitted in faded blue jeans, gray V-neck sweater, scotch-plaid flannel shirt and burnt-sienna chukka boots, the fifty-seven-year-old, silver-haired artist moved gazelle like across the dewy lawn, ushering his visitors into the pristine calm of his studio.

Inside the studio, a first impression was akin to visiting a new-car showroom, circa 1957, with chrome fenders and the high polish of metallic paint blinding the senses. Nine paintings in various stages of progress stood on caster-wheeled easels. German expressionist heads with bold diagonals of color stared at calmer yet harder-to-read brushstroke paintings of simple still lifes. With fifty paintings and nine sculptures already installed at the Saint Louis Art Museum, the platoon of easels immediately demonstrated that the artist was hell-bent on exploring a new wave of work.

Staring hard at the shimmering images of two sailboats, their red and white spinnakers puffed out to maneuver on choppy blue water, the artist asked hesitantly, “Can you tell what they are?” When I replied, “They’re making me seasick,” Lichtenstein laughed and moved over to another canvas in a less finished state. By far the largest of the new group, temporary cut-out strips of collaged brush strokes on the canvas created an unfamiliar depth to the sur-face. Taped to the bottom of the easel was a small drawing on acetate, a miniature of the towering canvas under which it rested. The lush strokes on acetate (the brush-stroked studies translate better on the transparent sur-face than on paper) are popped into an opaque projector that beams the enlarged image directly onto the desired canvas.

Stepping back from the canvas, I could make out a sunset sinking into the ocean as viewed through a grove of trees. A few feet away a large (also on wheels) mirror mimed the image. The artist’s wife Dorothy had looked at the painting and said she couldn’t make out the house. In an exaggerated moment of truth, before the impending punch line, the artist admitted the house wasn’t there—yet.

Under the Lichtenstein apparently fas-cinated with subject matter is a painter concerned with abstraction. Back in the early 1960s Lichtenstein had executed a long series of heroic brush strokes, abstract expressionist in style, but his new canvases read as exotic creatures from another hemisphere. One of the new works in the studio, Jar and Apple, just made it into the exhibition and onto the hand-some pages of the accompanying publication, Roy Lichtenstein 1970-1980, written by Jack Cowart (Hudson Hills Press, New York, 175 pages). To illustrate the difficulty of painting the new still lifes, Lichtenstein strode up to an easel, grasped one end like a roulette-wheel croupier, gave a whirl and the vertical canvas rotated to a horizontal position. “When I first did brushstrokes, they looked like strips of bacon. I don’t know if I talked myself into them or if they now really do look like brush-strokes.” The temporary realignment upset the still life and transformed the composition into a brash, abstract one. Two easels away, parked next to a flame-red track bike, stood the original rotating easel that Lichtenstein designed back in Ohio in 1951.

The assembly line of paintings that dominated the white-planked center of the studio camouflaged the scores of drawings, prints, and sculpture fluttering on the walls and wedged between packing crates and work tables. A bronze-cast expressionist head stared fiercely into space, waiting for element-beating coats of Bostic airplane paint. Standing fifty-five inches high, the flat-chested beauty slaps most notions of the third dimension in the face. Lichtenstein has managed to remain faithful to his first love, Surface, while flirting with depth and at the same time successfully creating a full-blown object. Like its peers in the museum show—the Matisselike Gold Fish Bowl, the steaming vapors of Cup and Saucer III, and the gold and amber rays from Lamp on Table—the sculptures are succulent editions in his ever-exploding repertory.

Despite the incontrovertible proof—”You can spot a Lichtenstein 500 yards away,” as art dealer Ivan Karp is fond of saying—it is still difficult to fathom how the artist could pro-duce so much work of such high quality in a ten-year span. Lichtenstein modestly attests, “I work from 10 A.M. to 6 P.M. with all sorts of interruptions”—casting a revengeful eye toward the studio Touchtone phone. “I’m waiting for the day that’s really ten in the mor-ning to six at night without any interruptions. Working on all the paintings is time-consuming. But what else am I going to do?” He bursts out laughing. “If I didn’t paint for three days I think I’d go crazy I love to paint. I’m very uneasy when I’m not doing it. The last thing in my mind is to stop working.”