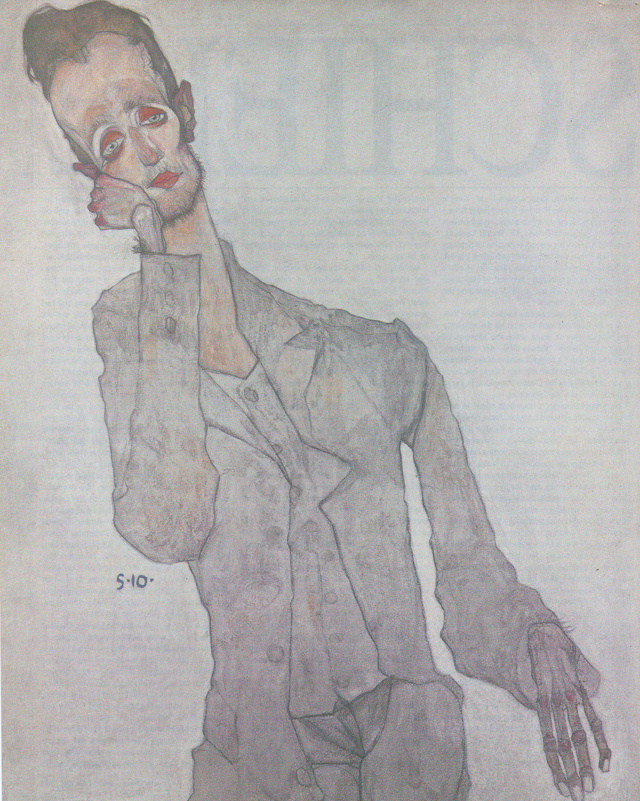

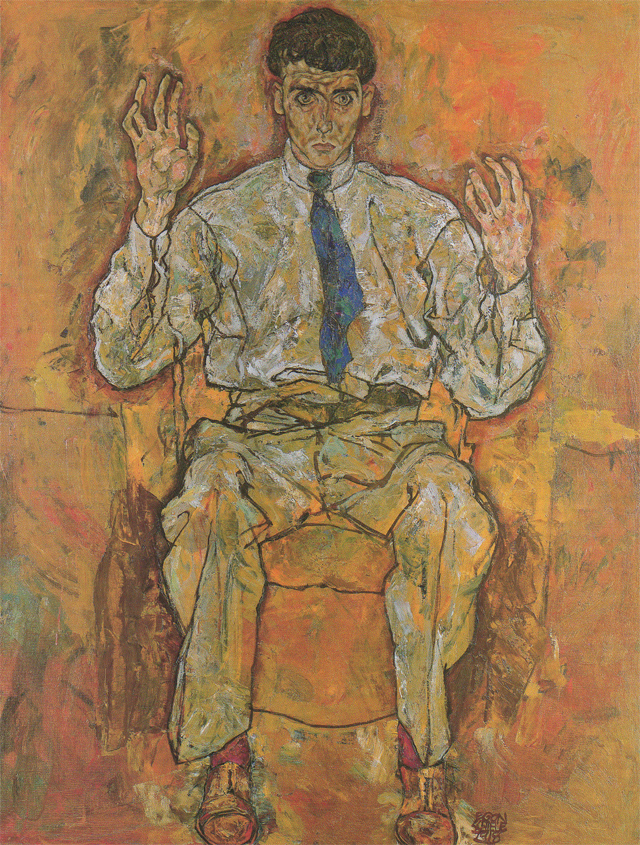

Portrait of the painter Karl Zakovsek (1910), which was sold two years ago at Sotheby’s for $2.4 million.

Collectors of art are beginning to discover Egon Schiele, and intense expressionist painter who died nearly seventy years ago.

Egon Schiele’s 1910 Portrait of the Painter Karl Zakovsek is wrought with tension. Paper-thin, eyes rimmed with fatigue, the sitter props his whiskered chin with a scrawny wrist. Although obviously seated, Zakovsek appears supported by thin air. The chair is invisible. There is no background to the painting, only the gessoed canvas. Zakovsek’s head and hands stick out. Every gesture is exaggerated.

Egon Schiele was twenty years old when he painted Zakovsek—a fellow artist and member of the Neukunstler group, a short-lived association that sent shock waves through the conservative cultural elite that ruled Vienna. Conversationalists in stuffed sitting rooms must have been at a loss to explain the minimalist setting or even the pose that mimick-ed Vincent van Gogh’s 1890 Portrait of Dr. Gachet (now in the Louvre).

Two years ago in New York, Schiele’s portrait of Zakovsek was auctioned at Sotheby’s for $2.4 million, a spectacular-enough bid for the New York Times to compose a large headline. The painting was previously owned by a New York doctor, who had purchased the oil in 1959 from a private gallery for $5,000. The extraordinary auction price was not a fluke. Less than a year later, in December 1984, Schiele’s Man and Woman was auctioned in Lon-don for $3.8 million. And just last May, at a most-ly disastrous sale of modern and impressionist works in New York, Sotheby’s sold Schiele’s 1917 oil Summer Landscape for $2.5 million.

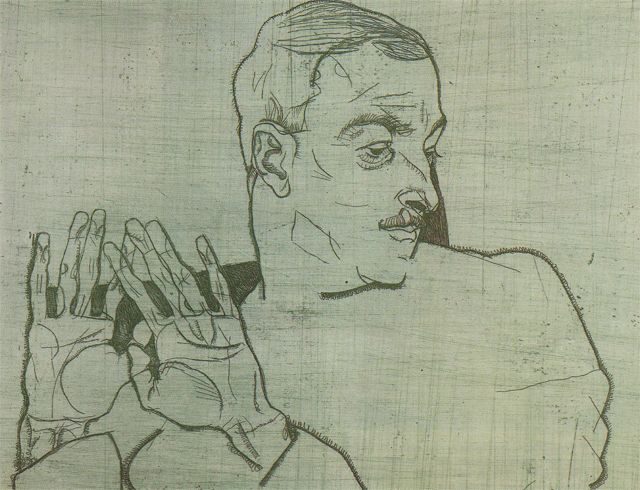

Portrait of Arthur Roessler (1914). Roessler was an early biographer of the artists and the first to recognize Schiele’s talent

Despite the existing list of English titles on the life and work of Schiele, two major publishing proj-ects are currently under way. Jane Kallir, codirec-tor of Galerie St. Etienne in New York, is assem-bling “the first comprehensive catalogue raisonne of the oils, watercolors, and drawings” alongside a complete Schiele biography (including, for the first time, entries from the diary of Schiele’s wife Edith, kept during their brief marriage). Ms. Kallir is the granddaughter of the late art dealer and historian Dr. Otto Kallir, who first exhibited Schiele in America at his Galerie St. Etienne, which he founded in 1939.

Just across town, on Madison Avenue, the international art dealer (and organizer of Schiele museum shows from Rome to Tokyo) Serge Sabarsky is collaborating on a five-volume book project with his colleague in Vienna, Dr. Rudolf Leopold. Leopold harbors the largest collection of Schieles in private hands and has already published a lavish coffee-table book on Schiele. But Dr. Kallir’s ground-breaking catalogue raisonne of paintings, first published in Vienna in 1933, is winning the horse race to hardcover.

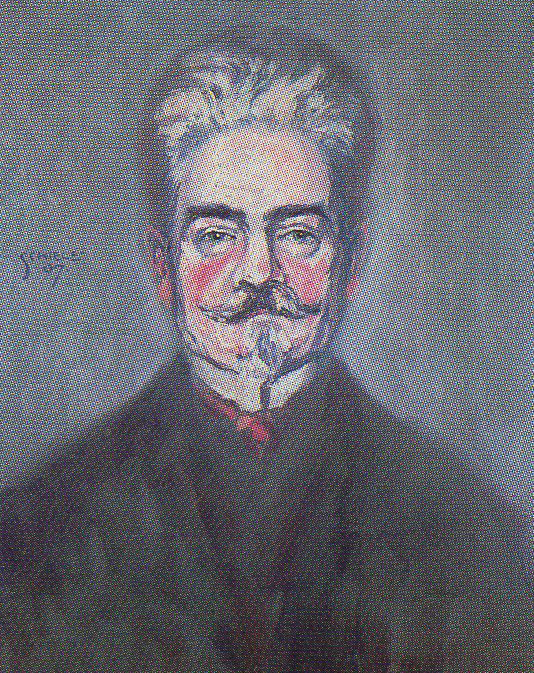

The conservative Czihaczek, Schiele’s uncle and guardian, disapproved of and often criticized his nephew’s lifestyle.

In July of 1986, summertime visitors to New York will get a firsthand look at what all the scholarly and auction fuss is about when the Museum of Modern Art unveils “Vienna 1900—Art, Architecture, and Design,” a cropped version of the “Dream and Reality” show that originated there last sum-mer and traveled to the Centre Pompidou in Paris. Schiele will be a star attraction.

Yet Schiele is hardly a household name. In fact, even reasonably educated art appreciators often don’t know the name. Others are only familiar with his self-portraits or erotic drawings—unaware that Schiele’s landscapes forged an important link to his vision, as unique and powerful as his studio portraits.

Schiele lived in Vienna, a city renowned in the early twentieth century more for its composers, architects, and psychiatrists than its painters. His saga has been an agonizingly slow but steady rise from obscurity, further complicated by his tragic early death and the cataclysm of two world wars.

Like all riveting dramas, it contains a play within a play Schiele’s story and that of the men and women—during his lifetime and after—who both championed and sullied his name. When Schiele died in Vienna on October 31, 1918, during the last days of World War I at the age of twenty-eight—a victim of the great Spanish flu epidemic—he was convinced of his own artistic immortality. “After my death, sooner or later people will certainly praise me and admire my art. Will they do this as completely as they abused, mocked, slandered, prohibited, and misunderstood my art? Possibly. But now praise or misunderstanding do not matter any more!”

Squatting Woman (Portrait of Wally Neuzil), painted in 1913, Neuzil was Scheile’s lover and favorite model, aside from his sister Gertrude.

Even Schiele’s final words swirl in controversy. His early biographer and untiring booster, the art critic and writer Arthur Roessler (who wrote five books on the artist between 1912 and 1923) transcribed Schiele’s last words. A number of contemporary art historians scoff at the pedigree of these decidedly romantic phrases. But even if they are part fiction or Arthur Roessler’s precocious brand of “new journalism,” Schiele always believ-ed he was great.

In the fall of 1906, at the age of sixteen, Schiele was accepted at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna. Taking the same examination a year later, Adolf Hitler would be denied admission to the prestigious academy. In the early 1930s, when Schiele was posthumously branded a “cultural degenerate” by the Nazis (along with such living artists as Beckmann, Dix, Feininger, Grosz, Heckel, Kirchner, Klee, Kokoschka, Kollwitz, Nolde, Perchstein, Schlemmer, and Schmidt-Rottluff), Jews fleeing Vienna took with them works by the banished Schiele. Those refugees who reached America with Schieles under their arms formed the nucleus of his exposure on these shores.

The best thing that happened to Schiele during his three-year stint at the academy was meeting Gustav Klimt—the undisputed leader of Vienna’s avant-garde; a cofounder of the Vienna Secession; and a major influence of its offshoot, the Wiener Werkstatte (a kind of Viennese Bauhaus). Klimt took Schiele under his gold-leafed wing, introduced him to a number of important collectors, and stiff-armed opposition to his participation in the prestigious 1909 International Kunstschau. Better contemporary company could not have been found, with such “foreign” artists as Munch, Matisse, Bonnard, and Vuillard participating. Schiele was still under Klimt’s stylistic spell, and it would take another year for the eighteen-year-old artist to develop his own recognizable style.

Death and the Maiden, a 1915 work using Wally Neuzil as a model.

The difficulty of this artistic transition was, in part, connected to his dependence on his uncle and guardian, Leopold Czihaczek. Schiele’s father, a stationmaster in the village of Tulln on the Danube, had died in 1904 (apparently of complications resulting from syphilis)—leaving a wife, two daughters, and one son. The many portraits of Uncle Leopold—the white goatee, cigar, high collar, and top hat—reveal his quintessentially conservative outlook. He did not approve of Egon’s life-style and even criticized his nephew’s all-but-indecipherable handwriting—as angular and tense as his drawings. Egon wished for a relative like van Gogh’s brother Theo and constantly wrote letters to his uncle and mother for money to support his efforts. He bitterly complained of his cast-off clothes and paper collars. An entirely different im-pression is gained after reading an “eye witness” account from Schiele’s Neukunstgruppe colleague, the painter and writer Paris von Giitersloh (Schiele’s 1918 unfinished portrait of his friend Paris hangs in the Minneapolis Institute of Arts, the first American museum to purchase a Schiele oil): “Egon Schiele was unusually handsome and had nothing at all artistic about him: his hair was not long, he never had even a day’s growth of beard, his fingernails were never dirty, and he never wore poor-looking clothes. He was an elegant young man whose good manners contrasted with what at that time was his poor painting technique.”

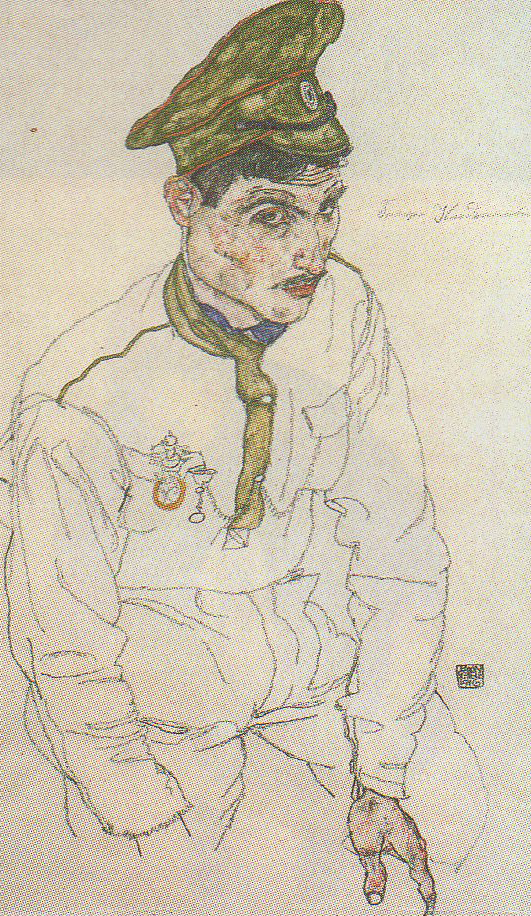

Russian Prisoner of War (1916). Scheile’s special privileges in the war included guarding prisoner’s, which freed him to draw the war and it’s people.

In what became a restless pattern of leaving Vienna for fresh-air bouts in the countryside, Schiele, in the spring of 1910, headed for the town of Krumau, his mother’s birthplace. He became close friends with an odd-looking couple, Moa and Erwin Osen—a dance-performance duo which, according to the English art historian Frank Whit-ford, contributed many ideas to Schiele’s dramatically posed portraiture that at times required a contortionist’s flexibility. Osen, for example, visited asylums to study the gestures and expressions of the inmates. Schiele’s continual need for nude models—including children—further alienated him from the towns rimming the Bohemian forests.

Through the matchmaking of Klimt, Schiele met, and quickly became enamored with, the model Wally Neuzil. Aside from his sister Gerti, no other model occupied so much of his time. In the rich assortment of volumes filled with Schiele reproductions, the red-haired radiance of Wally dominates. Her stare is both sultry and innocent.

The uncomfortable fact that Schiele was obsessed with the most intimate female anatomy (explicitly focused on sexuality—including masturbation) got him in trouble in 1912 in the town of Neulengbach, in 1960 in the metropolis of Boston (site of his first American museum exhibition), and even in Rome in 1966, when police seized a number of drawings right off the walls of the Marlborough Gallery and branded them “offensive to public morality.”

Thomas M. Messer, director of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York and veteran organizer of three major Schiele exhibitions (two in the United States and one in Germany), recalls his delicate position as director of Boston’s Institute of Contemporary Art in 1960 (when the ICA was still tied to the staid Metropolitan Boston Art Center). “Schiele was high on my agenda. There was quite a disagreeable visit from a Met official, and a lot of fancy skirmishing as to the permissibility of works took place. I did not at all exaggerate the erotic dimension, but even with a fairly tactful selection, it still did not go unchallenged.”

The Neulengbach episode in April of 1912 wrenched Schiele from his idyllic surroundings and brought him to the brink of insanity. His house was raided by police; over one hundred drawings were confiscated. He was charged with seducing a minor. Tossed into prison, deprived of his drugs—paper and pencil—he made drawings with his own spit, which evaporated before his eyes on the clammy cell walls. His original diary, as well as the official court records, is lost, but a judge did burn in open court one of Schiele’s erotic drawings and plunged the artist into a two-year period marked by self-portraits in monkish robes and shorn hair, his body pitifully thin.

The famous portrait of the painter Paris von Gütersloh (1918). Schiele’s indelible black signature anchors the image at the foot of Paris’s tie shoes.

After the trauma of Neulengbach, Schiele’s for-tunes changed rapidly. Under the critical and often tempestuous guidance of Roessler, Schiele’s reputa-tion bloomed. He was picked for important inter-national exhibitions in Cologne (where he showed alongside the Blaue Reiter group), Brussels, Munich, and Vienna. Schiele was so intent on show-ing and selling his work that he impetuously mailed off a rolled stack of drawings (shielded only by flim-sy wrapping paper) to the premier Munich art deal-er Hans Goltz. Goltz gave Schiele a one-man show in 1913.

Back in Vienna, Schiele rented a large studio residence and rapidly courted his neighbors, the Harms sisters—finally choosing Edith to be his wife. He dropped the loyal Wally in favor of bourgeois respectability. She never recovered, volunteering as a field-hospital nurse on the front in the early part of the war and soon succumbing to scarlet fever. Schiele married Edith in 1915, on the eve of his induction into the Austrian army.

Although he only lived to be twenty-eight, Schiele created over three thousand works on paper and close to three hundred oil paintings. Even in the emperor’s army, Schiele had special privileges, shielded from the front and mostly assigned to guarding Russian prisoners of war. His pencil raced over paper like a cavalry charge—never retreating to erase—capturing the expressions, postures, and dress of vanquished Russians and his fellow soldiers and documentary depictions of the well-stocked army commissary. The Great War hampered his oil painting output, but to him the war was a mere inconvenience.

“After my death, sooner or later people will certainly praise me and admire my art.”

Schiele’s finest hour—in the twilight of World War I—was his showing at the Vienna Secession in March of 1918. Honored with designing the ex-hibition poster, Schiele had a room to himself in the cabbage-headed Secession building. Nineteen of his most important and recent paintings, plus a selection of watercolors and drawings, brought both critical and financial success. It also revealed a marked change in style—softer and more voluptuous in its treatment of color and form. Death stop-ped this new style in its tracks, half formed and overwhelmingly seductive.

Egon Schiele, shortly before his death in 1918. At the time of his death, the artist was convinced of his own artistic immortality.

Unlike the beige shroud that suffocates the emaciated 1910 portrait of Zakovsek, the 1918 Portrait of the Painter Paris von Giitersloh is fully fleshed and firmly planted on a cushioned chair. The intentionally significant placement of the painter’s hands—posed as a boxer and ready to jab, but with a brush—takes precedence over every other element. There are no props to distract. His eyes are open wide, and it is close to the epiphanic moment of artistic inspiration when the artist will leap off that chair. The artist’s raised hands surrender to the impulse of creation.

Reading through the thick volumes of press clip-pings at the Galerie St. Etienne, I came across an astute observation of the Guggenheim’s Messer. “Schiele’s capacity to shock has not been lost or substantially diminished by the passage of time.” When Dr. Kallir mounted Schiele’s first American solo in 1941 (he introduced a galaxy of European expressionists to America), a newspaper critic observed, “Death lurks behind every shape.” Dur-ing a second solo in 1948 (like the first, a financial flop), New York Times critic Sam Hunter wrote that Schiele was “particularly masterful in nervous structural line and macabre vision.”

By the time of Schiele’s first museum exhibition at Boston’s ICA in 1960, Time devoted two pages “to the half-forgotten Austrian expressonist,” kin-dling the myth of his “hand-me-down suits” and “handmade paper collars.” When the Guggenheim staged its major Schiele show in 1965, one critic observed, “His understanding of the male and female bodies must have been as a cannibal’s.”

Schiele’s power to entrance collectors, critics, and curators is a mixture of myths based on a desire to anoint an artist cut down in his youth too soon to see where he would take his genius. Schiele—as seen through the mirror of his self-portraits—was tortured by his own sexuality and obsessed with the notion of martyrdom: a Saint Sebastian riddled with arrows. The beautiful, full-length portrait of his pregnant wife Edith, finished in 1918 only months before she succumbed to influenza, quivers with the expectation of a calmer world, never to be witnessed by Edith or Egon.

The contorted anguish that had stalked his earlier pictures was extinguished by new brushstrokes. From his church-tower landscapes to his deathbed sketches of Klimt, Schiele carried his world of lovers, patrons, and fellow artists to paper and can-vas. Whether garbed in the red vestments of a car-dinal or the brown sackcloth of a hermit, Schiele painted himself on the edge of a changing world.

Dr. Kallir’s prophetic exhibition title, “Saved from Europe: Masterpieces of European Art,” in the summer of 1941 began Schiele’s odyssey in America. This past summer, standing in the center of the Serge Sabarsky Gallery, surrounded by a roomful of Schieles, the accumulated myths of the artist merged with the palpable reality of seventeen canvases. Face to face with Uncle Leopold, the hag-gard Zakovsek, Wally as the Madonna, and Egon staring out from a mountain of rumpled bedclothes, I could only wonder why the odyssey of recogni-tion has taken so long.