[The black and white photos of Warhol at work: Top left Andy with art dealer/publisher Ronald Feldman, upper right, shooting Uncle Sam with his Polaroid, Andy with a Zebra print from Endangered Species & studio assistants screen printing.]

(by comparison Pablo Picasso registers 49 prints realized in that seven figure category).

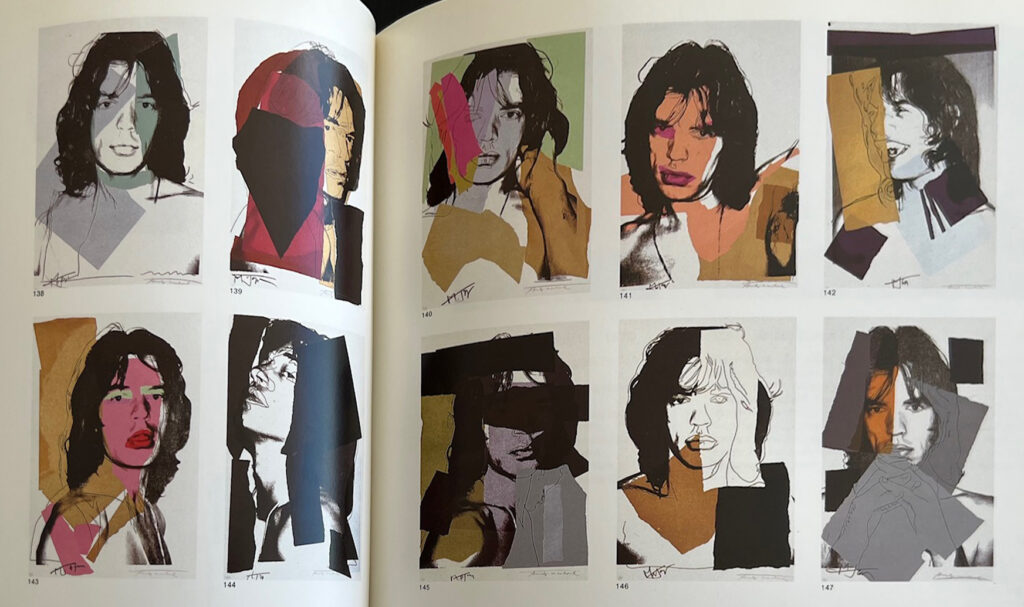

Looking back, an early example of Warhol prints at auction was a single 44 x 29 inch print of Mick Jagger from 1975, from the portfolio of 10 screenprints, #30 over 225, sold for $935 against an estimate of $700-900 at Christie’s East in November 1986.

Another single print from that same edition went for $157,500 at Phillips’ Editions sale in New York last Thursday that took in a house record $6.3 million for the 358 lots that sold.

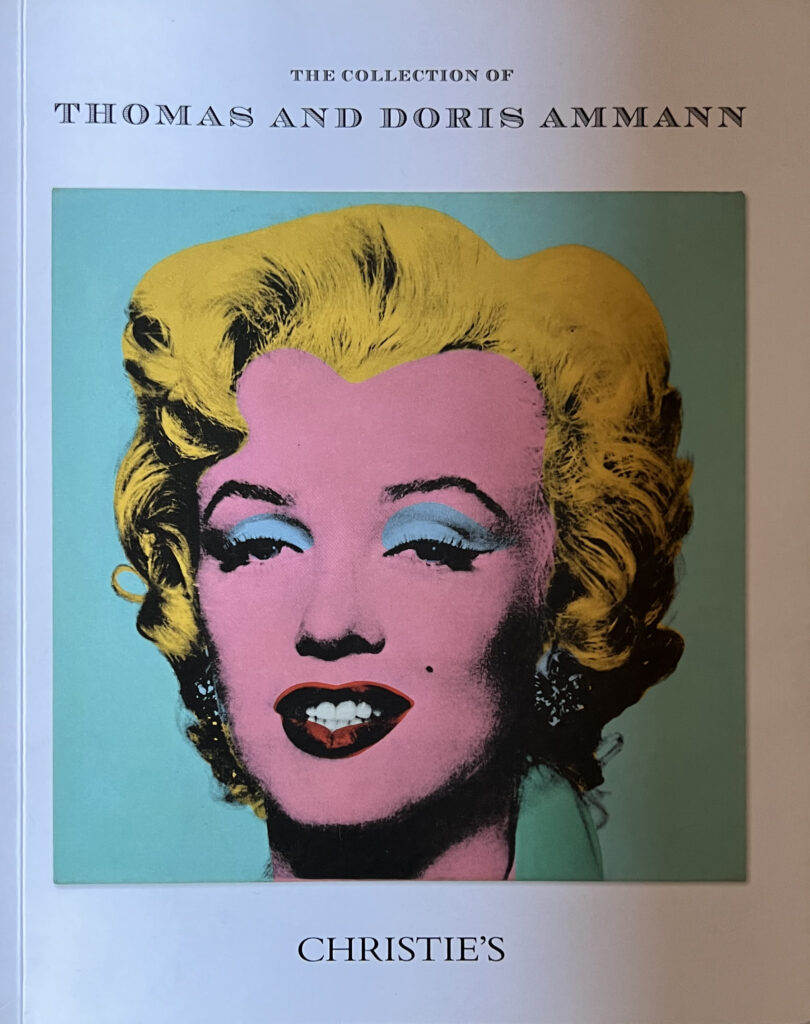

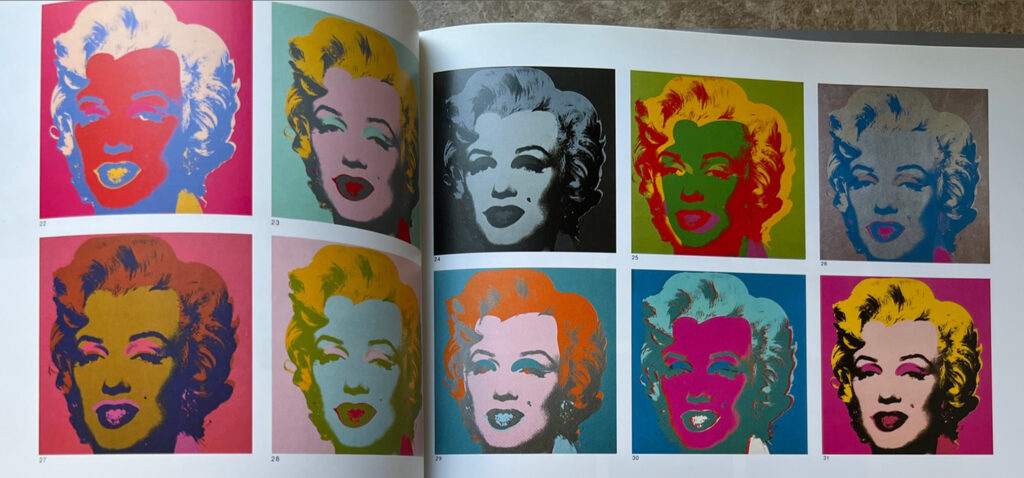

In Warhol’s stunningly prolific mix of prints, the top gun is not so surprisingly “Marilyn Monroe (Marilyn)” from 1967 that fetched $4,980,000 at Christie’s New York last May against a pre-sale estimate of $1.5-2.5 million.

It hails from an edition size of 250 & each of the ten prints in various colors measure 36 by 36 inches each.

You can do the simple math & figure that each print in that set went for close to $500,000 a piece, including fees.

This one, signed & stamped in pencil and numbered with rubber stamp on the verso, is #108 over 250. There are also 26 artist proofs signed and lettered A-Z on the verso.

There was nothing special or at least noted in the catalogue description in terms of provenance or other interesting tidbits that might have juiced the price higher.

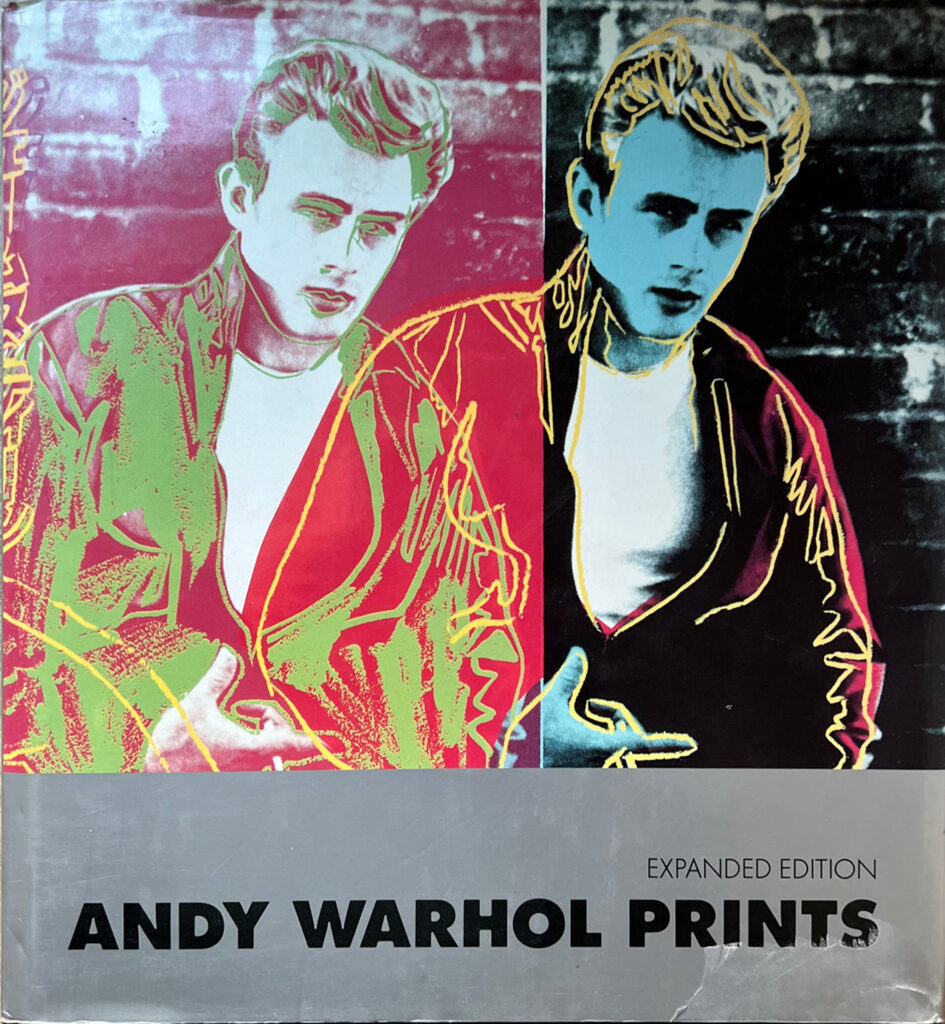

This information regarding print size and the like, and for the rest of the examples that will be cited today hail from the authoritative & bible like first edition from 1985 of the Andy Warhol Prints catalogue raisonne edited by Frayda Feldman and Jörg Schellmann & with essays by the late curator & bon vivant Henry Geldzahler as well as critic/biographer Roberta Bernstein as well as an interview with Rupert Jasen Smith (1953-1989), the longtime Warhol printer from 1977 marking his first work with the “Hammer and Sickle” portfolio up to “Moonwalk” in 1987, the year of Warhol’s death.

The publication is critical to the understanding of this part of Warhol’s oeuvre. (& is still available on sites like Amazon).

As noted curator Donna de Salvo described Warhol’s innovative medium in the 2003 edition, “Through his conceptualization of the printing process, Warhol transformed that process into his metaphor for America—its capitalism, its abundance, its industry, and, most important, its simultaneous and contradictory desire for innovation and uniformity—Marcel Duchamp meets Norman Rockwell meets cable television.”

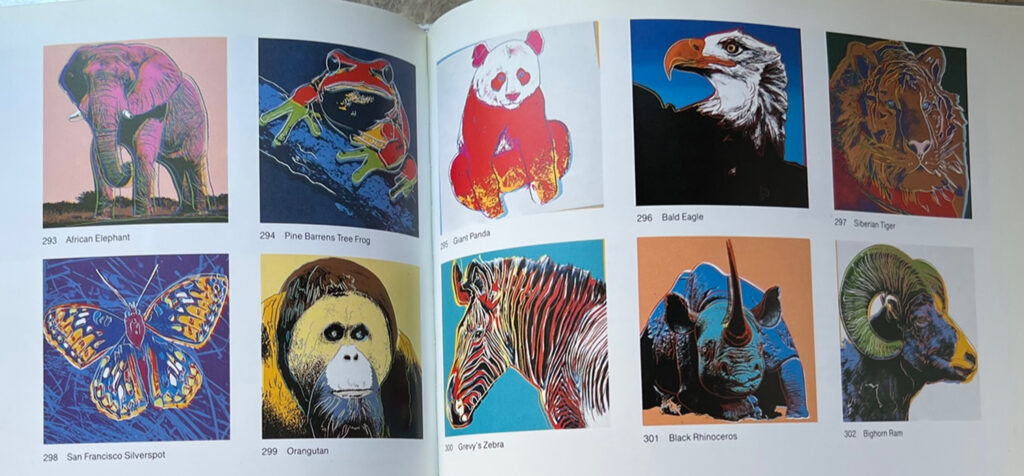

Surprisingly, at least to me, the second highest Warhol print price at auction lands with the much later “Endangered Species” portfolio from 1983 and hailing from an otherwise unidentified Japanese collection that made £2,919,000/$4,054,729 against an estimate of £350-550,000 at Sotheby’s London in March 2021.

It was #125 over an edition size of 150 with each of the ten prints ranging from an African elephant to a Siberian tiger, measuring 38 by 38 inches. You can add in another 30 Artist Proofs, 5 Printer’s Proofs, 5 Exhibition Proofs & 3 Hors Commerce (reserved for collaborators in the process).

During a recent phone interview I had with Cary Leibowitz, the deputy chairman and world-wide co-head of Editions at Phillips as well as a visual artist, observed “you can also find a lot of the late ‘70’s going into the ‘80’s work, that had not been in as high regard of earlier stuff, has a whole new market and that whole new international group of buyers—right now, an Endangered Species set can make the same price as a Marilyn set. Somebody might feel,” Leibowitz notes, “the Marilyn is too campy or old fashioned for them and they like the animals and they like the colors of the later stuff.”

Beyond that, though conceived and executed in 1983, the series today is on the cutting edge of mounting concern with Global Warming and the disappearance or danger list of so many species.

Leibowitz characterizes that ‘whole new generation of collectors’ in the 30-60 age bracket and who don’t know “the whole back story of Warhol.”

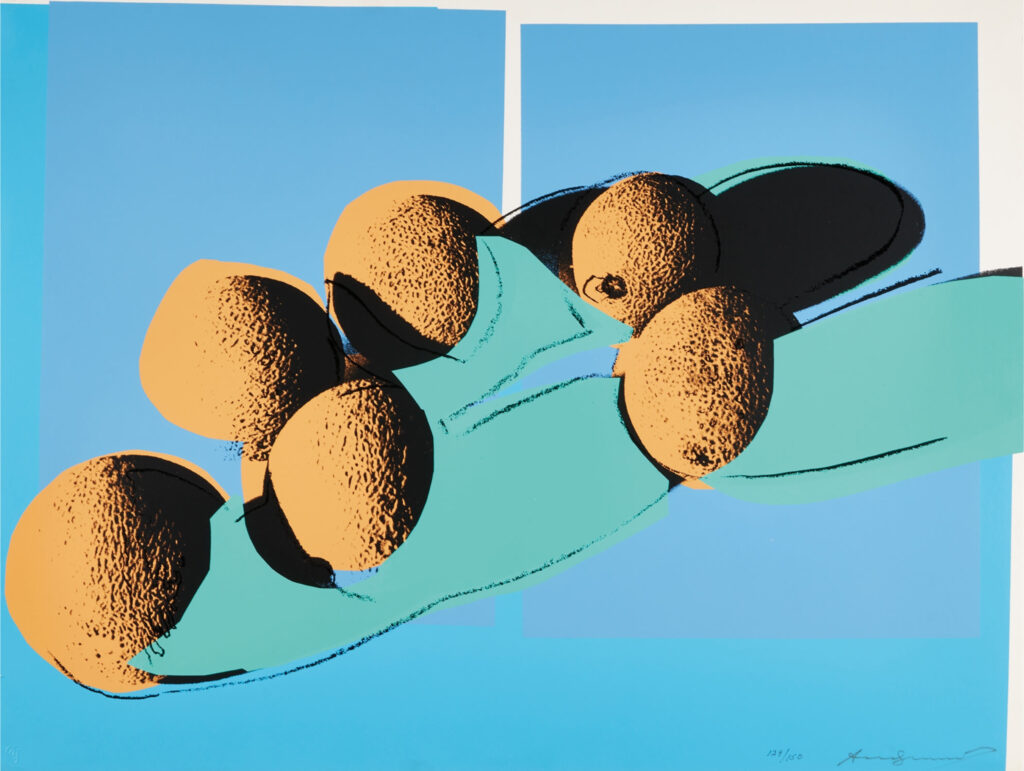

“Space Fruit: Still-Lifes” from 1979

For that reason, or so it seems, formerly underappreciated series like “Space Fruit: Still-Lifes” from 1979 have shot up in price and are in higher demand at auction.

The next three top prices in the database are also for the 10-part Marilyn portfolios followed by “Flowers” from 1970, #57 of 250 that made €2,141,000/$2,594,208 against an estimate of €800,000 -1 million at van Ham Kunstauktionen in Cologne Germany in June 2021.

It hailed from the legendary Helga & Walther Lauffs Collection in Krefeld & no doubt its celebrated provenance boosted its market desirability.

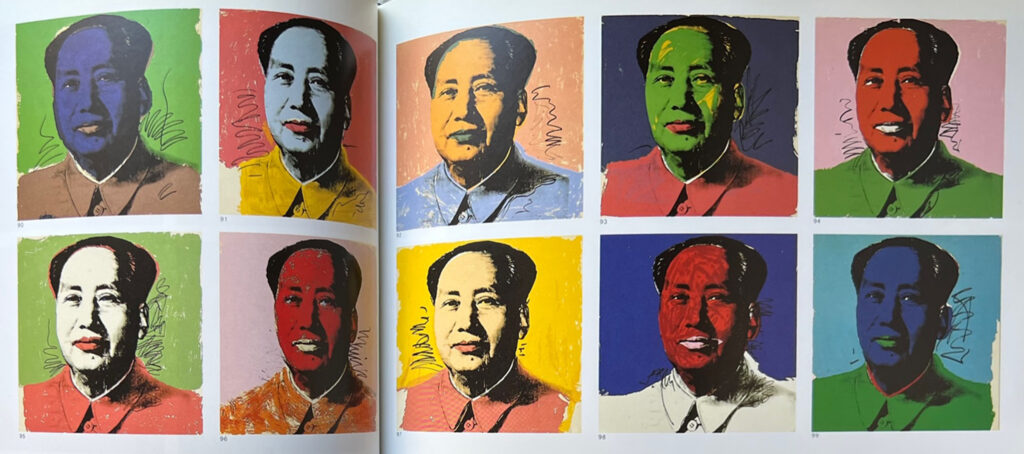

Next in line price wise carries another notable provenance tag line with “Mao” from 1972, #1 from an edition of 50 plus 50 artist proofs that made £1,609,250/$2,538,649 at Sotheby’s London in May 2012. It was sold by the estate of global playboy, photographer, industrialist and collector Gunter Sachs.

The Mao portfolio from Castelli Graphics and Multiples marks an important variant in Warhol’s oeuvre, as Leibowitz explained, in that for the first time the artist used freehand on the screens so you’ve got the brush work, some black lines in dialogue with the screen image of Mao as well as using a layer of varnish. It’s unusual since as Leibowitz states of Warhol, “he’s a machine, he doesn’t touch things.”

Flicking back for a moment to the artist’s prime Pop Art years, “Campbell’s Soup I” from 1968, with each print measuring 35 x 23 inches and number 129 from an edition of 250 sold for £1,026,800/$1,445,179 against an estimate of £300-500,000 at Phillips London in June 2021.

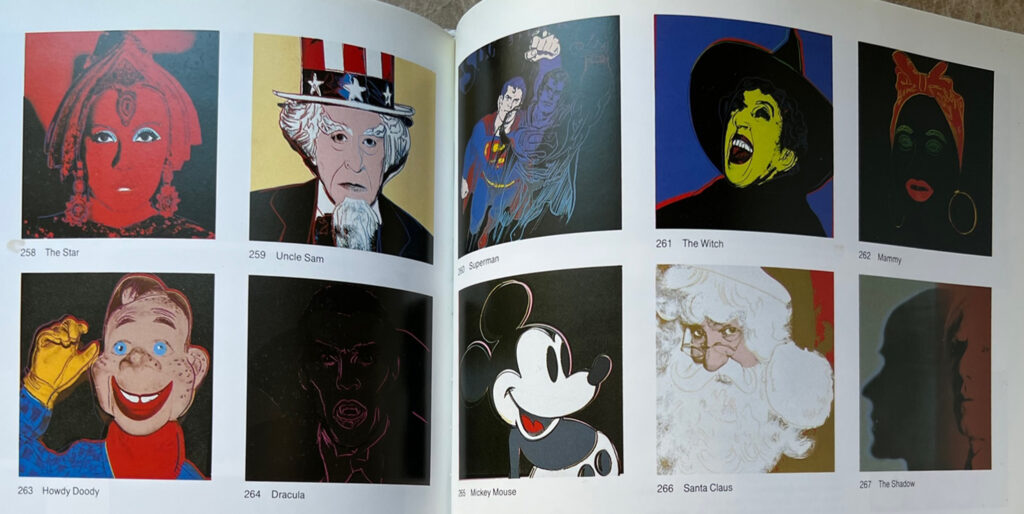

Whether early or late, Warhol’s print oeuvre remains the gold standard, like another ‘80’s standout, the “Myths” portfolio with #17 over 30 of Trial Proofs realized $1,085,000 against an estimate of $500-800,000 at Christie’s New York back in November 2014.

All of the ten American as apple pie images, ranging from Howdy Doody to Superman, but not Dracula, are sprinkled so to speak with diamond dust.

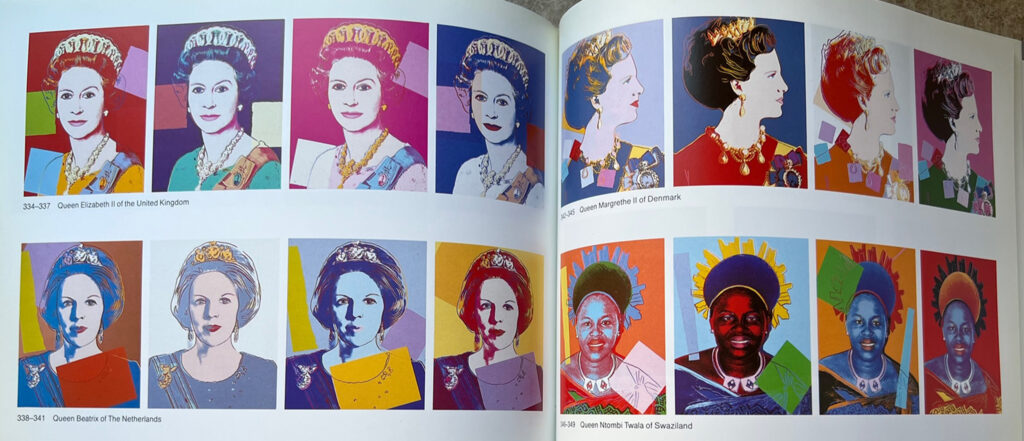

Completed in that same decade and just two years before Warhol’s death at age 57, a single print of Queen Elizabeth II from the “Reigning Queens” portfolio from 1985 and measuring 39.4 x 31.5 inches soared to £554,400/$641,073 against an estimate of £150-250,000 at Sotheby’s London on September 14, 2022.

Lucky for Sotheby’s (& the seller who acquired the print in the ‘80’s) Queen Elizabeth passed away on the 8th of that month at Balmoral Castle, making that sale a kind of heavenly homage.

(Another Queen Elizabeth II print from that series made $352,500 against an estimate of $200-300,000 at Philips on Thursday, underscoring the point that timing is pretty much everything).

The portfolio of 16 screenprints in an edition of 40, includes the lesser- known visages of Queen Margrethe II of Denmark, Queen Beatrice of the Netherlands and Queen Ntombi Twala of Swaziland.

As Leibowitz observed of Queen Elizabeth, “She’s a little bit like Marilyn Monroe, so iconic.

By contrast, a single print of the Queen of Swaziland may garner $12,000 and that of Queen of the Netherlands in the region of $50,000.

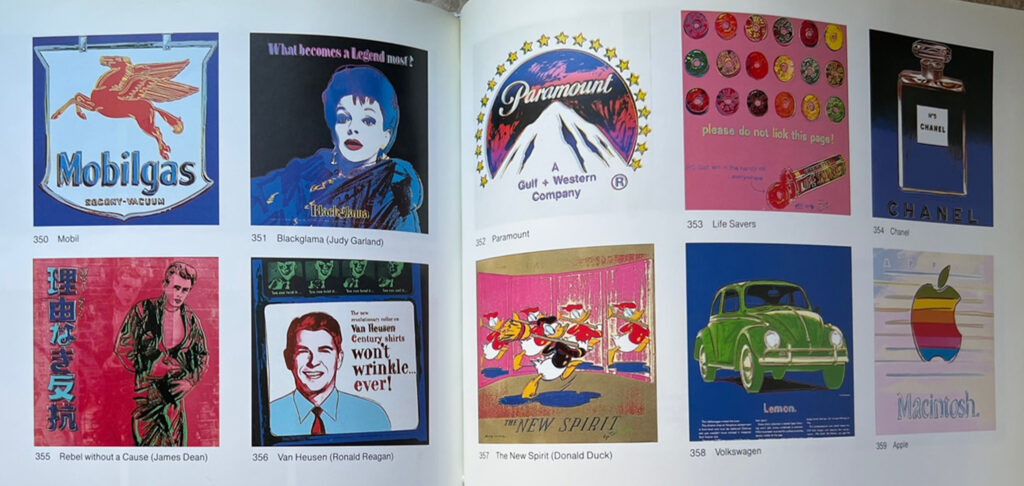

Another late in career edition, “Ads” also from 1985, including the screen gem likes of James Dean and Ronald Regan and storied brands such as Chanel #5 and the ‘old’ Apple logo exude Warhol’s ode to Capitalism.

A set of ten, with each sheet measuring 38 by 38 inches from the trial proofs #13/30 sold for $1,025,000 against an estimate of $500-800,000, at Christie’s New York back in November 2014.

Going back once more to the Marilyn prints of 1967, some folks might wonder how in the heck did “Shot Sage Blue Marilyn” from 1964 and scaled at 40 by 40 inches in acrylic and silkscreen ink on linen fetch a record shattering $195,040,000 at Christie’s New York last May, the highest price ever achieved for an American artist.

How do you make sense of that enormous gap between linen and paper since the highest price recorded for a single Marilyn print was $378,000 (estimate $200-300,000) in October 2021 at Phillips New York?

Leaving that question in part to Cary Leibowitz, the specialist said, “right now the difference is really just what collectors have made of it. The painting is a painting, a print is a print. You could say a painting has its own unique history & its own unique provenance and the prints come out in an edition of 250, so they’re definitely a multiple—but if you’re breaking it down by a screen making process, there isn’t much of a difference, so it’s really more about the metaphysical aspect of the object itself.”

Leibowitz also brought up an interesting but long forgotten fact of how some museums in the 1960’s used to categorize and place Warhol works in their print departments because they were all screen printed. Obviously, that has changed!

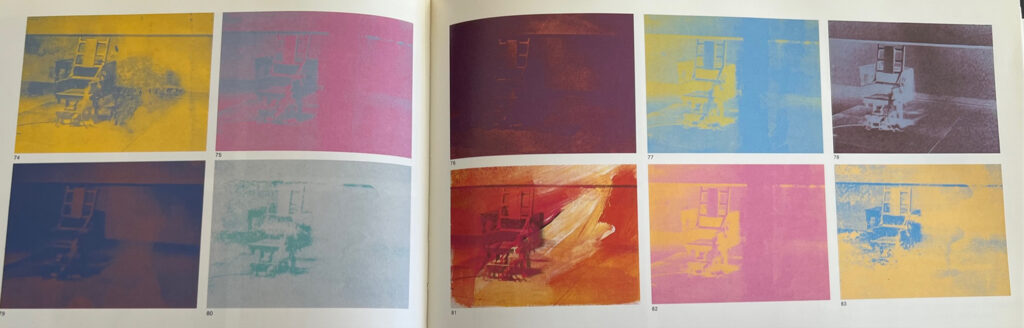

In closing, if you’re looking for art historical importance in any of Warhol’s series, the trophy would go to Warhol’s multi-colored “Electric Chair” from 1971 published by Bruno Bischofberger in Zurich in an edition of 250.

At Christie’ New York last May, a complete set of ten sold for $466,200 against an estimate of $200-300,000, a tenth of the price of a top Marilyn portfolio, & considerably larger, image wise at 35 ½ by 48 inches.

Then again, not many people would want those disturbing and rather terrifying images hanging on their dining room wall.