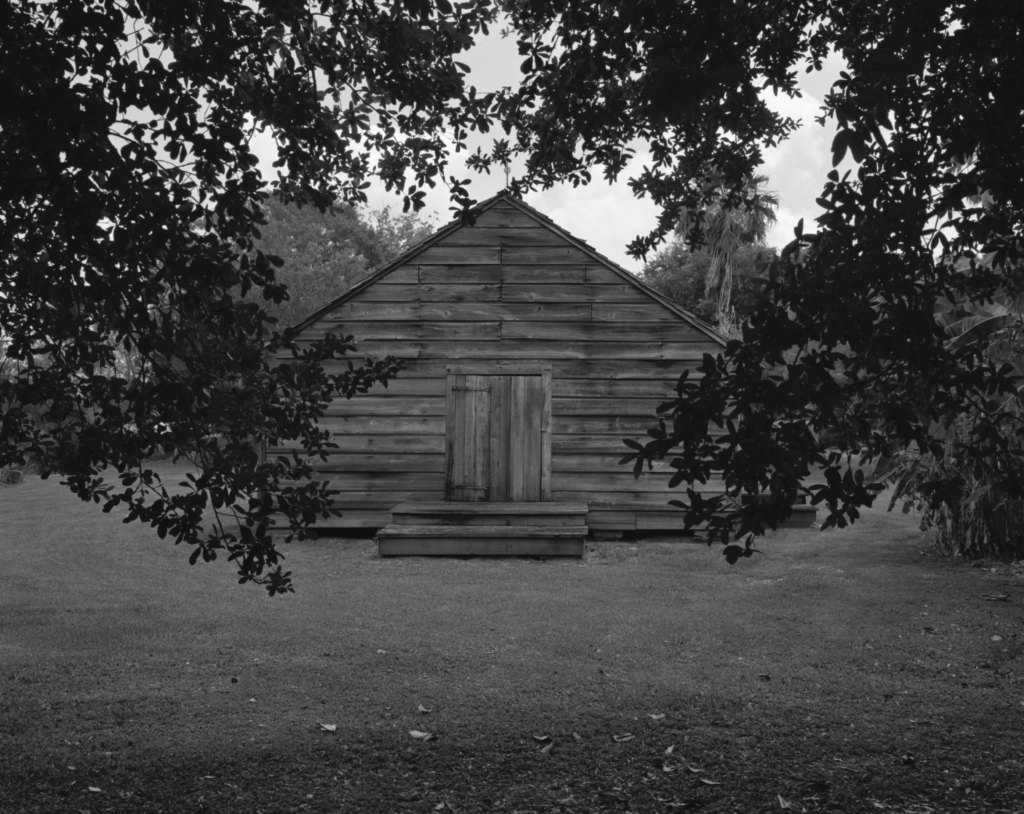

Trees and Barn, 2019, gelatin silver print, framed: 49 x 60 x 2 inches (124.5 x 152.4 x 5.1 cm) edition of, 6 with 2 APs, (DB-ITHP.19.04.2)

There are still a few more days to catch Dawoud Bey’s superb photography exhibition, “An American Project” at the Whitney Museum of American Art that covers distinct bodies of work dating from the late 1970’s black and white street portraits in Harlem to the subtly searing and completely imaginary and large-scale landscapes from 2017,“Night Coming Tenderly, Black,” tracking the perilous flight of enslaved Black Americans following the last leg of the Underground Railroad to freedom.

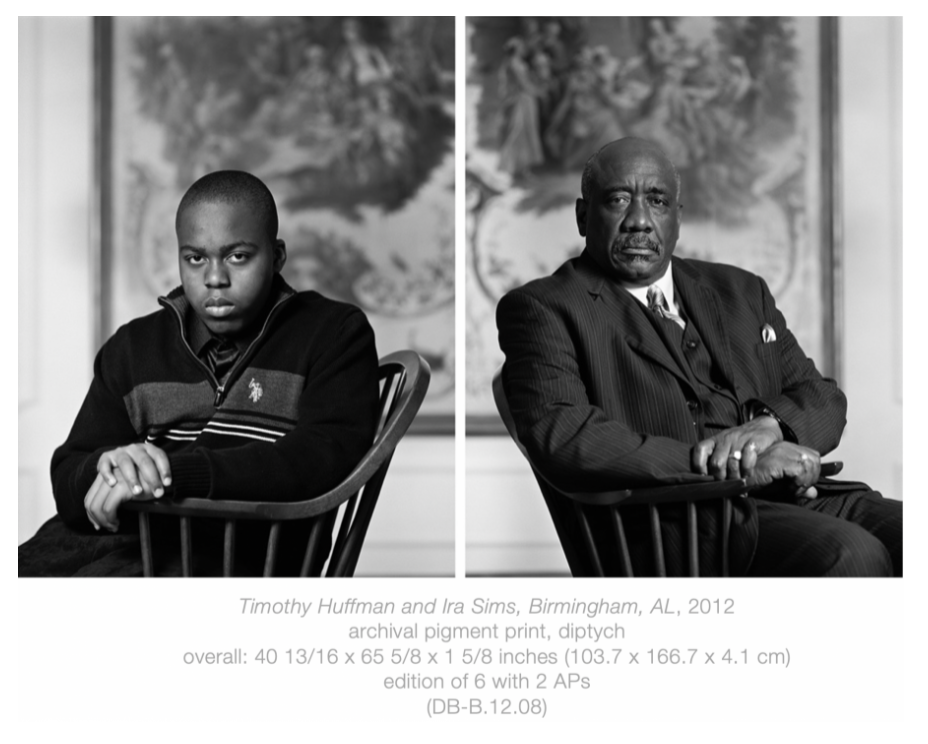

In between those stellar bodies of work reflecting the roving eye of the young street photographer capturing the essence of life in Harlem to a fully developed artist recasting the story of slavery in America, are photographs of teenage youths in Syracuse, New York, Washington, D.C., Harlem and Brooklyn, as well as paired diptychs of local residents in his “Birmingham Project” from 2012 reflecting on the September 15,1963 racist bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama that killed six African-American adolescents.

Bey’s photographic journey at the Whitney records both his artistic growth and mastery of various picture taking and printing techniques such as the 20 X 24 Polaroids from the early 1990’s of friends and family, shot through the lens of the giant, 240 pound Polaroid camera that the company made available to a number of artists and photographers, ranging from Ansel Adams to Robert Rauschenberg.

The exhibition also includes examples of Bey’s “Harlem Redux” series from 2014-16 of pigmented inkjet prints documenting the wildfire gentrification of the neighborhood, including images of a boarded up and impossible to otherwise identify Lenox Lounge, the longstanding Harlem bar and performance venue for famed Jazz artists.

Bey not only tells stories about the past, of what was needed to be remembered or brought back to life in some kind of filtered light, but works through complex issues as a kind of cultural historian (think of say Lewis Hine), one with his finger on the shutter push-button.

A stunning example of that approach is Bey’s “9.15.63“ split-screen, single channel video installed in the museum’s lobby gallery that takes the viewer through a sunny, seemingly innocent Sunday car ride through the quiet streets of Birmingham, leading to the church and the horror that occurred there.

The slow tracking video also records, without a human in sight, the interior of a local barbershop and a café, reminders perhaps of putting on your Sunday best.

The exhibition was co-organized by the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and scheduled to open there in February 2020 though Covid interfered and essentially erased that important West Coast venue for Bey.

If you miss the Whitney show or crave a topper to it, the Sean Kelly Gallery is staging Bey’s “In This Here Place,” comprising a new series of large-scale, 49 by 60 inch gelatin silver prints capturing the mostly abandoned or derelict plantations of Louisiana, a place where “the relationship between the enslaved and America was formed” (as accurately stated in the gallery press release).

Akin to “Night Coming Tenderly, Black” that reprised a stanza of Langston Hughes’ poem “Dream Variations,” the new series appropriates an opening line of Toni Morrison’s “Beloved.”

Again, the beautifully printed landscapes (from an edition of six plus two artist proofs) of the spartan cabins and lush Spanish Moss trees are absent of any human figures, other than perhaps lingering ghosts or imagined memories of what life must have been like for the people that lived and hard labored on the sugar cane fields there.

The work, as visually stunning as it is, simultaneously conveys a haunting and even menacing presence.

The titles are simple and descriptive, such as “Open Window” and “Trees and Barn,” without a hint of editorial opinion and leaving the viewer to form one’s own reaction to a barely recorded time and place, one that Bey, in a sense, has resurrected.

The exhibition which also debuts Bey’s three-channel video, “Evergreen,” runs through October 23rd.