The art of David Hammons is covering the island of Manhattan from the freshly installed public art piece “Days End,” a Conceptual homage to Gordon Matta-Clark sited by the Hudson River at Pier 52, just across from the Whitney Museum to The Drawing Center in SoHo featuring some 38 works from his storied Body Print series.

On Saturday, May 1, a third blast of the artist’s multi-faceted oeuvre, “David Hammons: Basketball and Kool-Aid” opens at Nahmad Contemporary on Madison Avenue.

The stunning combination of the two distinct series, ranging in time from 1995-2012, offers a deep voyage across the artist’s elusive practice. There are six examples of his glass framed and found object bound basketball drawings along with a recreation of a 1998 untitled installation, including a steel basketball hoop, tree trunk and an African ceramic jug holding a basketball, as if it were some archeological treasure.

“David Hammons: Basketball and Kool-Aid” at Nahmad Contemporary on Madison Avenue, May 1 to June 25, 2021

They join ten of the artist’s ABEX epoch inspired Kool-Aid paintings on paper, some bearing terry-cloth artist made frames and silk veils to protect the delicate brew of the powdered pigments.

The two bodies of work unleash a full-court press on Hammons’ brilliance, both as an image-maker and unrivaled seer of contemporary culture.

Time Out (Basketball Drawing), 2004/2010 Graphite on paper with alarm clock Framed: 51 x 34.75 inches (129.54 x 88.27 cm)

“Traveling” from 2002, comprised of Harlem earth on paper with a black cloth suitcase wedged behind it and towering at 116 1/8 by 49 inches reverberates with the ghostly sounds of the game and the obsessive barrage of mark making executed with a dirt or graphite covered basketball dribbled and bounced across the paper surface like an Action painting.Much has been written about Hammons’ relationship to the game and with it, the hoop dreams of so many disadvantaged youths who pursue a demanding sport that enriches and makes famous so relatively few. And given that as art historian Kellie Jones has noted, Hammons is always thinking about language, Traveling, among its myriad of meanings, can also be seen as being in her words “about migration and moving and having to move.”

The drawings are enshrined and cocooned in elaborate, glass-covered gilt frames, as a Francis Bacon painting would, bringing along the viewer’s looking glass reflection.

Found objects, from a travel alarm clock, large stone to a broken pile of asphalt are attached to or sited as supporting pedestals to the works.

The cacophony of elements in these works bring to mind a carousel of references, from a pair of Michael Jordan worn Air Jordan sneakers from 1985 that fetched $560,000 at auction to images of playground pick-up games.

Better yet, Hammons titled one of his storied outdoor works, the bottle-cap festooned telephone poles with attached hoops “Higher Goals.”

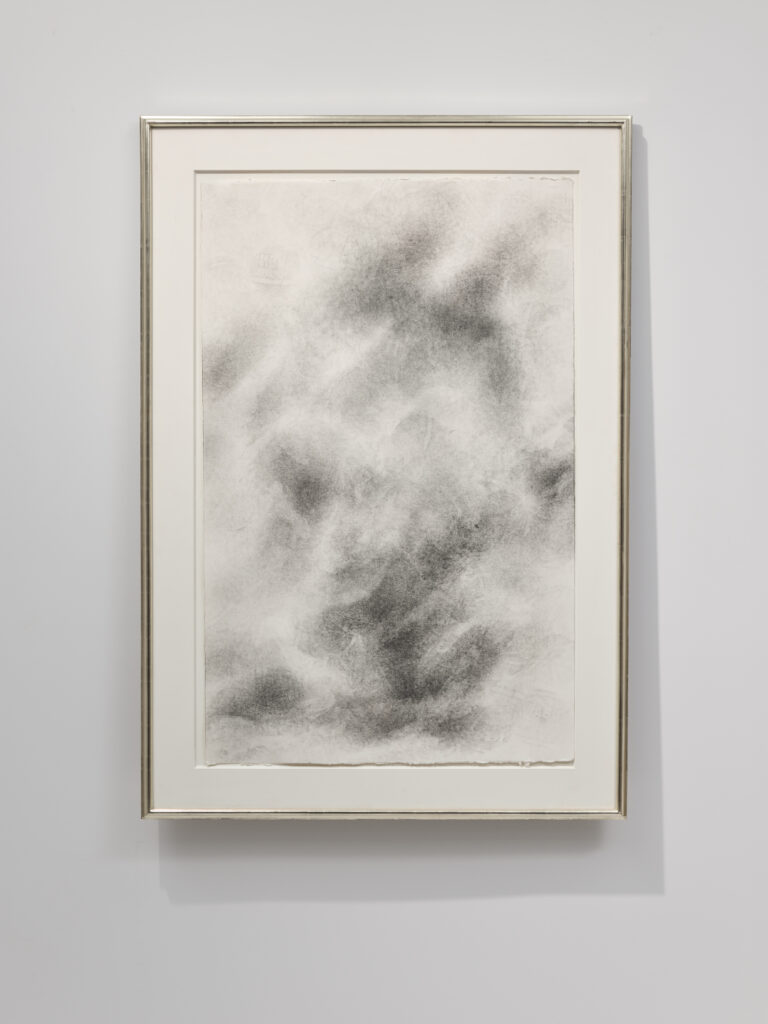

Untitled (Kool-Aid), 2006

Kool-Aid on paper with silk curtain and artist’s terry cloth frame

Framed: 43.5 x 29.5 inches (110.5 x 74.9 cm)

One might think anything apart from these iconic works on paper would be a tough act to follow but the Kool-Aid paintings (all titled “Untitled (Kool-Aid)” and dated between 2003 and 2008) astonish the eye in a somewhat different manner.

A number of the works reside behind silk veils, akin to protective coverings of light-sensitive photographs from the 19th century or for that matter, devotional objects kept behind velvet curtains in Renaissance times.

The witches’ brew of the Kool-Aid powders and electric colors that come with it, such as strawberry kiwi, peach mango and cherry limeade (yes, these are some of the official flavors and equivalent colors of the famously crafted and patented drink) form Hammons’ mind-altering palette. They become fantastical pastiches allied in part with the look of a Sam Francis or Helen Frankenthaler abstraction.

But it goes beyond those art historical references, as some of the Kool-Aid paintings are delicately inscribed in expertly rendered Japanese script with the actual recipe for making the concoction.

You might say that de Kooning and Pollock got high marks for using hardware store based house paints for their revolutionary works but I can’t imagine anyone apart from Hammons dreaming up Kool-Aid as an economical medium.

“David Hammons: Basketball and Kool-Aid” at Nahmad Contemporary on Madison Avenue, May 1 to June 25, 2021

The mere mention of that drink brings on another montage of references, from Tom Wolfe’s “Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test” (about the ‘60’s bred Merry Pranksters who spiked a vat of Kool-Aid with LSD and offered the beverage) to the darker chapter of the Jonestown massacre in Guyana in 1978 where the cult leader Jim Jones forced his commune flock to “drink the Kool-Aid,” a fatal mixture with potassium cyanide and that killed over 900 people.

Kool-Aid, at one time a General Foods brand, was also heavily marketed in low-income neighborhoods as a sweet and cheap drink with a significant portion of users from Latino and African-American households.

You can still buy vintage packets of the stuff on eBay and Etsy, all bearing the advertised image of the smiling “Pitcher Man,” with his disembodied face ‘drawn’ on the condensation sweat of the glass pitcher.

Even stripped of the Popular Culture references, these delicate works are visually luscious to behold, a trademark effect of his practice.