Judd Tully – 1985, photo credit: Sarah Wells

I started writing seriously about the art market as a stringer for the Washington Post Style section in late 1985.

My first article for them was that December, covering Sotheby’s American Paintings sale where a rare to market painting by Rembrandt Peale, “Raphael Peale with Geranium” sold for a record $4.07 million to the National Gallery of Art in Washington.

The portrait of the artist’s 17 year old bespectacled brother was the highest price ever paid at auction for an American painting and easily hurdled Peale’s former auction record of $82,500 set in 1972 for “Portrait of George Washington.”

Carter Brown, the late and great director of the National Gallery of Art was in the salesroom, seated up front next to Lawrence Fleischman of Kennedy Galleries who bid on the museum’s behalf.

I was instructed by my Style section editor to find Brown and interview him if he bought the painting.

Obviously, the Post, or so I surmised at the time, had been tipped off that this might happen.

I did as I was told, wrote up the article on my manual typewriter and dictated it over the phone to a Washington Post dictation clerk, requiring me to spell all the proper names under immense deadline pressure.

Rembrandt Peale, “Rubens Peale with a Geranium”, 1801, oil on canvas, 71.4 x 61 cm

The article appeared the next day on the front page of the newspaper (not in the Style Section) with my byline.

Looking back at what seems now like a pre-historic exercise also produced a couple of interesting points, such as:

In preparing these remarks, I looked up Peale on Artnet in order to check my recollection and to my surprise found the top price listed as “Equestrian Portrait of George Washington” that sold for $1,071,000 at Christie’s New York in December 2004.

There wasn’t a Peale geranium in sight.

The Artnet price database, founded in 1990 by Hans Nuendorf and six other partners and that now has over 11 million color illustrated art auction records dating back to 1985, at least according to Wikipedia, missed that remarkable moment.

The art trade, after all, lives on access to accurate information and this Peale anecdote simply illustrates the need for due diligence, not only about reporting on the art market but also in valuing, buying and selling art.

I had already written some articles about art fairs and auctions for publications like the New Art Examiner in Chicago & I recall one headline about an auction I covered, “Julian Schnabel Lays a Golden Egg.”

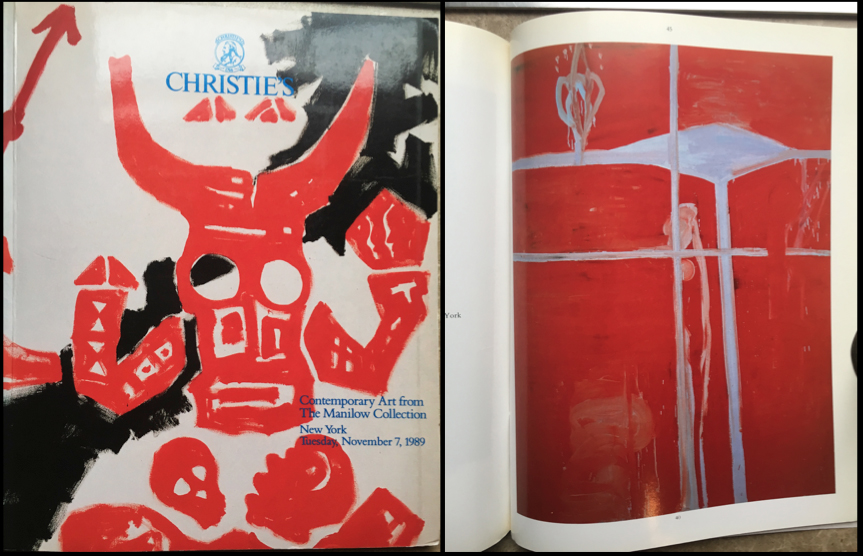

Christie’s Manilow Collection catalog, November 1989

In thumbing through my relatively vast & slightly organized archive, I came across a faded, Xeroxed price sheet from Sotheby’s Archives (that was a service provided by the auction house in the pre- digital age) that Schnabel’s “The Act” from 1982 sold for $200,000 hammer at Christie’s New York single owner sale of the Chicago based Manilow Collection in November 1989 (est. $80-120,000), certainly a jaw-dropping record at the time.

I’m not 100 percent sure that was the particular Golden Egg that sparked the headline, but it was certainly part of that frothy time.

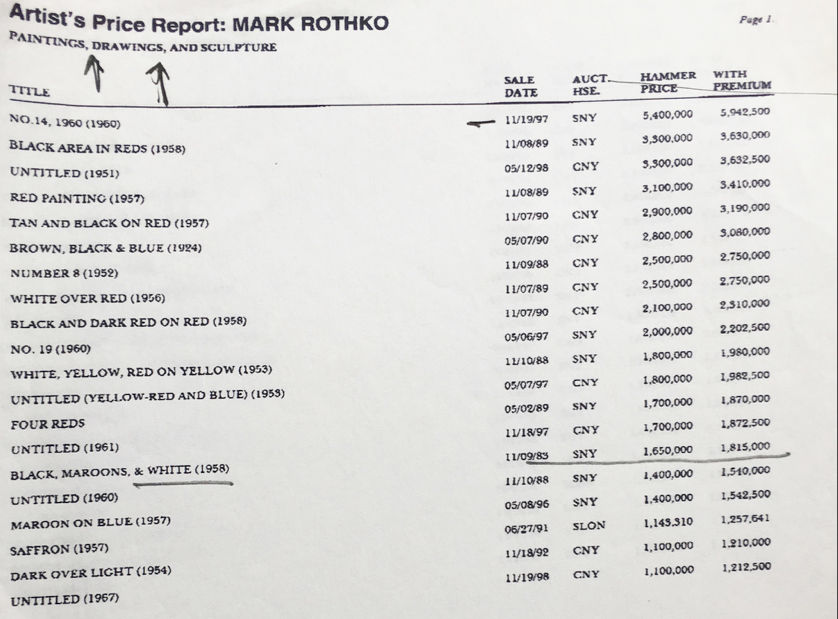

In those early days, I relied heavily on Sotheby’s crucial archive of “Artist’s Price Reports” that typically listed the top 20 prices of artists sold at auction for paintings, drawings and sculpture but in duopoly style, only covered those sales at Sotheby’s and Christie’s in London and New York.

There was also the encyclopedia like and ponderous Mayer International Auction Records that tracked some 900 auction houses from 1965 to 2005.

I would go to a cavernous room at the New York Public Library on 5th Avenue and pick through the volumes for past prices of works sold at auction.

It was always of interest to me to see how auction prices fluctuated and what seemed sky high at one moment looked dirt cheap at another.

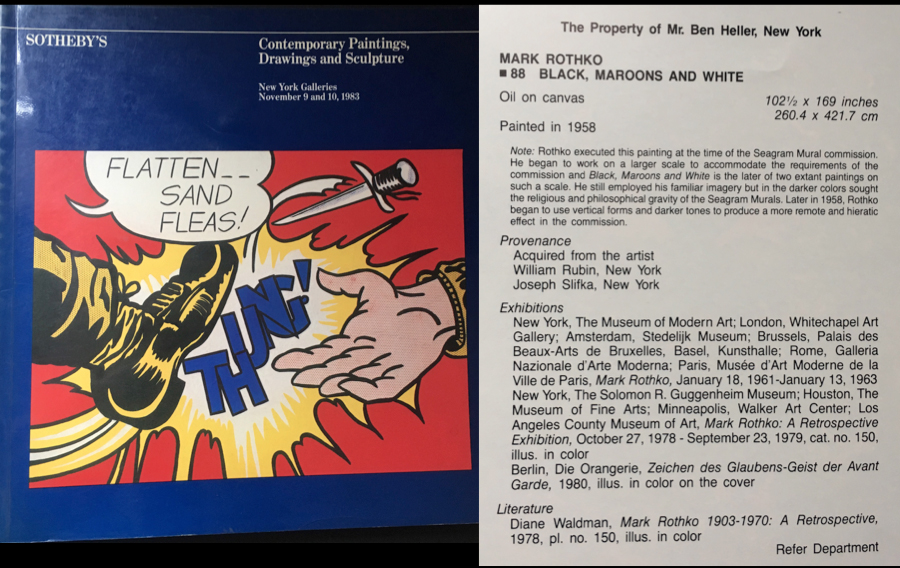

Sotheby’s Contemporary Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture sale catalog in November 1983

A case in point and one that I didn’t witness first hand was the Sotheby’s Contemporary Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture sale in November 1983 when the evening’s last lot, Mark Rothko’s magisterial and widely exhibited “Black, Maroons & White” (at 102 1/2 by 169 inches) from 1958, completed at the time of the Seagram Mural commission and consigned by storied New York collector Ben Heller, sold for a record $1.65 million. The estimate was “Refer Department” only, meaning they didn’t really know how to gauge it.

It was the first seven figure Rothko sale at auction.

Sotheby’s “Artist’s Price Reports” that typically listed the top 20 prices of artists sold at auction for paintings, drawings and sculpture

Since that time, 120 Rothkos have made over a million dollars at auction, 25 over $20 million and seven over $50 million, topped by “Orange, Red, Yellow” from 1961 that sold for $86.8 million at Christie’s New York in May 2012 against an estimate of $35-45 million.

What would Heller’s painting be worth today? $100 million? $200 million? More?

I’ll take educated guesses from you later.

Rothko, of course, is a stellar figure in the AB-EX pantheon and it is still remarkable to note how his prices have changed over decades of trading.

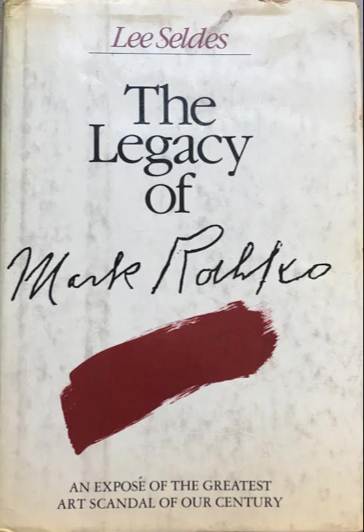

Lee Seldes’ “The Legacy of Mark Rothko-an Expose of the Greatest Art Scandal of our Century” (published by Holt Rinehart & Winston in 1978)

Leafing through my dog-eared copy of Lee Seldes’ “The Legacy of Mark Rothko-an Expose of the Greatest Art Scandal of our Century” (published by Holt Rinehart & Winston in 1978), a few startling facts about Rothko’s posthumous market jump off the page.

In the Surrogate Court lawsuit against the artist’s dealer Frank Lloyd, the major domo of Marlborough Gallery and the three executors of Rothko’s estate, “Matter of Rothko” that the artist’s daughter, Kate Rothko, under the auspices of the New York Attorney General, sued for self-dealing, tampering with evidence and other machinations, it came out that Marlborough cut a deal with the estate to pay $1.8 million over a period of twelve years for 100 paintings.

Dealer Richard Feigen had offered to pay cash at four to six times over that figure and the aforementioned Ben Heller estimated in the summer of 1972 that the value of the 100 Rothko paintings had increased to between $70,000-125,000 per painting, adding up to a $7-12.5 million price tag for the group.

During the course of the three month long trial, Rothko’s “Yellow and White,” an undated canvas at 68 by 58 inches, sold at Sotheby’s New York in May 1974 for $110,000 hammer, in line with Heller’s earlier estimation.

In any event, Lloyd and the executors were found guilty as charged.

Lloyd escaped the prison sentence recommended by the prosecutor and wound up paying $100,000 in providing art education to New York City public school students.

Marlborough was expelled from the Art Dealers Association of America. All things considered, barely a slap on the wrist.

The Seldes’ page-turner proved to be another primary source in my early art market education.

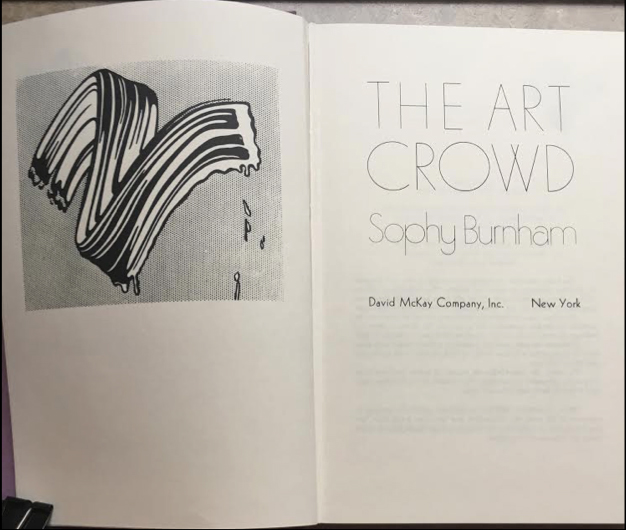

‘The Art Crowd,” published by the David McKay, Company, New York in 1973

An even earlier primer that helped me navigate through the smoke and mirrored art world was Sophy Burnham’s ‘The Art Crowd,” published by the David McKay Company, New York in 1973. I paid $12.50 for it at the Strand and it proved to be definitely worth it.

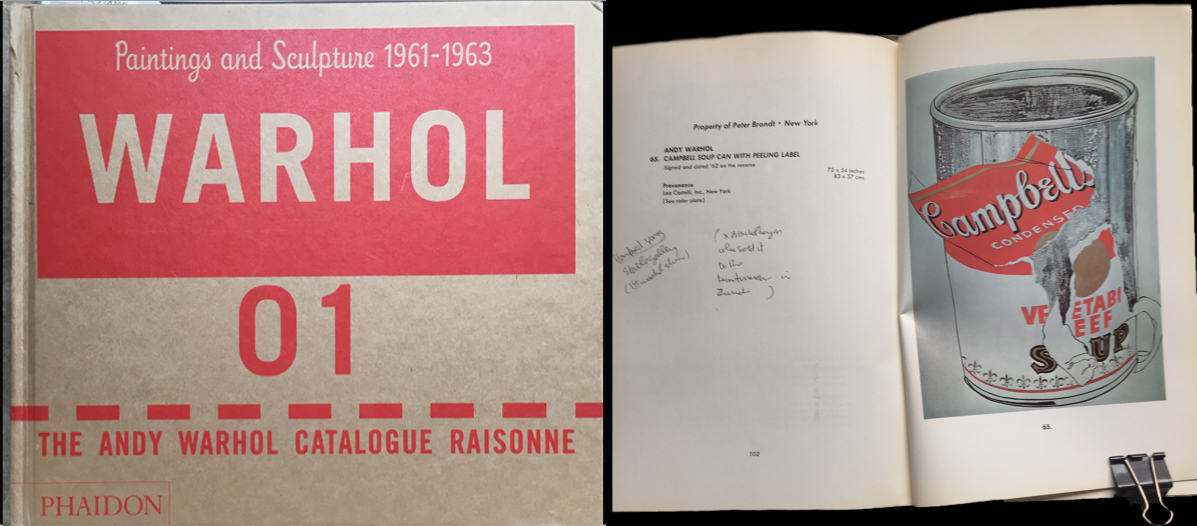

One of the chapters from Sophy Burnham’s ‘The Art Crowd,”, dwelled in part on an Andy Warhol painting, “Campbell Soup Can with Peeling Label,”

One of the chapters dwelled in part on an Andy Warhol painting, “Campbell Soup Can with Peeling Label,” from 1962, executed in casein, gold paint and pencil on linen and grandly scaled at 72 by 54 inches, that was sold, according to the property title in the Parke-Bernet Galleries’s May 18, 1970 evening sale catalogue by Peter Brandt (spelled with a ‘d’).

Auction catalogues at that time didn’t include printed estimates or were available to some insiders on a separately printed sheet.

In Burnham’s account, the Warhol sold for a record $60,000 to an unknown bidder and marked the first time a major Warhol had appeared at auction. No dealer price had exceeded $50,000, according to the author and the painting was expected to fetch around $40,000.

Burnham surmised that Brandt teamed up with Swiss dealer Bruno Bischofberger to push the bidding up and actually bought the painting.

It later became available at Bischofberger’s Zurich gallery for $75,000.

“Both Brandt and Bischofberger denied the allegations,” wrote Burnham, “that the picture was bid up to establish a higher market. But a record price for Warhol had been established.”

The provenance trail in volume one of the Andy Warhol catalogue raisonne of paintings and sculpture 1961-63 ends with Bischofberger.

The account, for many reasons, put me on permanent journalistic guard for observing and reporting on auctions.

After another fortuate find at the Strand Book Shop on Broadway, I often checked “The Great Art Boom: 1970-1997” by Christopher Wood and published by the Art Sales Index Ltd of Surrey England to check that ebb and flow.

The Art Sales Index, founded in 1968 by Richard and Bridget Hislop, set out to record art prices on computer “for the first time in history,” according to Wood.

The Art Sales Index, founded in 1968 by Richard and Bridget Hislop, set out to record art prices on computer “for the first time in history,” according to Wood.

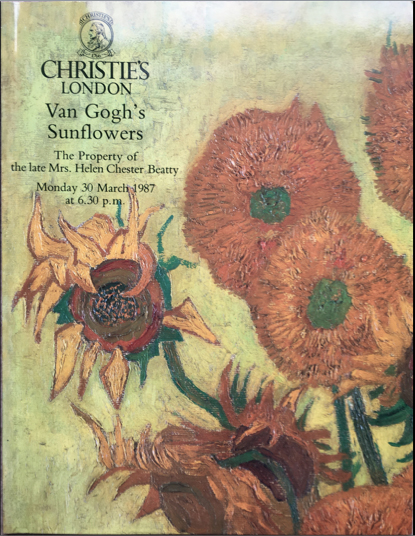

The book jacket cover color photograph shows the outstretched tuxedoed arm of Christie’s London chairman Charles Allsopp auctioning Vincent van Gogh’s “Sunflowers” from 1889 on March 30, 1987 when it fetched a then astonishing and record £22.5/$36.2 million hammer, selling to the Yasuda Fire & Marine Insurance Company. At the time, the most expensive painting ever sold at auction. It was also the harbinger of the late 1980’s art boom that lasted for approximately 44 months.

“Sunflowers” held onto that mark for barely eight months until van Gogh’s “Irises” made $53.9 million at Sotheby’s New York in November 1987 when it sold to the Australian entrepreneur Alan Bond.

(As it turned out, Bond received a $27 million loan from Sotheby’s prior to the auction in order to acquire the work but eventually defaulted on the loan and the painting ultimately sold privately to the Getty for an undisclosed price and where it still resides).

The fact that news accounts at the time of the sale trumpeted the fact of such a huge and record price coming less than a month after the fearsome Wall Street financial market crash on October 19th, made the art market appear reassuringly bullet proof.

Pontormo, Portrait of a Halberdier (Francesco Guardi?), 1528 to 1530, Oil (or oil and tempera) on panel transferred to canvas, 95.3 × 73 cm

Taking a momentary breather from van Gogh’s rocketing market from that time, a handful of other artists were also making headlines, including the 16th century Florentine Old Master, Pontormo, aka Jacopo Carrucci, whose stunning “Portrait of a Halberdier (Francesco Guardi?)” fetched $35.2 million at Christie’s New York in May 1989.

The portrait of the 19 year old duke sold to the Getty Museum and according to George Goldner, the Getty’s acting curator of paintings at the time, “you could say it was a bargain.”

The price realized tripled the previous mark for an Old Master at auction, outgunning Andrea Mantegna’s “Adoration of the Magi” that brought the equivalent of $10.45 million at Christie’s London in April 1985 when it also sold to the Getty.

The Pontormo, in turn, retained the record price for any Old Master sold at auction until July 2002 when Sir Peter Paul Rubens’ “Massacre of the Innocents” sold at Sotheby’s London for £49.5/$76.7 million. The Rubens still holds the auction record for an Old Master.

I probably need to clarify, given the rapid way art auction marketing is changing, that the Pontormo as well as the Rubens sold in Old Master evening sales, unlike the “last” Leonardo Da Vinci painting, “Salvator Mundi” that will be offered this coming week at Christie’s Post-War and Contemporary Art evening sale sporting a $100 million, third party backed estimate and paired for publicity sake with a massive, Andy Warhol “Last Supper” painting from 1986 that is expected to bring about $50 million.

Peter Paul Rubens, Massacre of the Innocents, 1610, oil on panel, 142 × 182 cm

Post-War and contemporary art also rocketed to new heights in that late ‘80’s window as evidenced in part by Willem de Kooning’s bravura masterwork, “Interchange” from 1955 that sold for a record $20.68 million (estimate $4-6 million) to Tokyo dealer Shigeki Kameyama of Mountain Tortoise Gallery at Sotheby’s New York in November 1989.

It was sold from the estate of Edgar J. Kaufmann, Jr. who acquired it from the Sidney Janis Gallery in the year it was painted for $4,000, according to dealer David Janis, the grandson of the gallery patriarch.

It set a record for any work of contemporary art sold at auction, hurtling past the mark set by Jasper Johns’ “False Start” that made $17.1 million in November 1988 and helped to propel Sotheby’s evening tally to a then whopping and almost unheard of $98.3 million.

But like the “Irises” sale, Kameyama couldn’t complete the purchase since he apparently went far beyond his client’s direction and wound up making a post-sale deal with Sotheby’s to swap and consign a number of works for the house to sell in order to pay for “Interchange.”

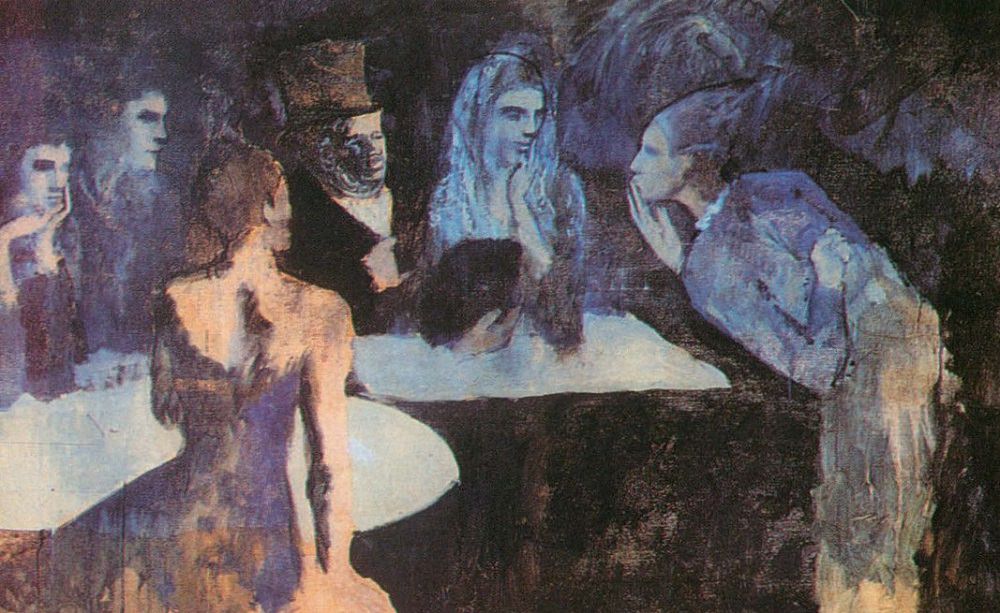

In 1989, Picasso’s Les Noces de Pierrette was sold for FF 315 million/$51.65 million.

At some point in time, Los Angeles collector David Geffen acquired the work privately and Geffen’s foundation subsequently sold it to Chicago hedge fund magnate Ken Griffin for a reported $300 million in 2015.

“Interchange” now hangs in the Art Institute of Chicago, a stone’s throw from Jackson Pollock’s “Number 17 A” from 1948, another work Griffin bought from Geffen, thanks to long term loans from the new owner.

But not to stray too far from the boiling cauldron of art transactions of the late 1980’s, the story returns to Picasso and the artist’s piercing self-portrait, “Yo Picasso” from 1901, a key work that appeared in the Museum of Modern Art’s blockbuster, building wide retrospective in 1980, snared a record $47.85 million at Sotheby’s New York in May 1989. It was estimated at $15-20 million.

But a bigger sale almost went unnoticed that November—at least in the New York press—when Picasso’s haunting, Blue Period masterwork, and one long thought to have been destroyed, “Les Noces de Pierrette/The Marriage of Pierrette” from 1905 sold for the pre-Euro price of FF 315 million/$51.65 million at Drouot Binoche & Godot in Paris, certainly a record for Picasso at the time.

It sold to the Japanese real estate and race track mogul Tomonori Tsuramaki.

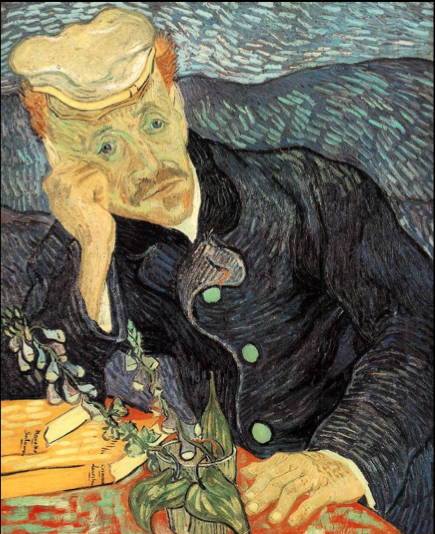

Vincent van Gogh, Portrait of Doctor Gachet, 1890, Oil on canvas, 67.0 x 56.0 cm.

You won’t find Pierrette on Artnet—and I’m note sure why– though it did appear on a Christie’s press office prepared list from 2004 of Top Prices Achieved at Auction since 1985

I was honored to see a reference to my Washington Post article about that Paris sale, “The Mystery of the Masterwork” cited in John Richardson’s Volume I “A Life of Picasso.”

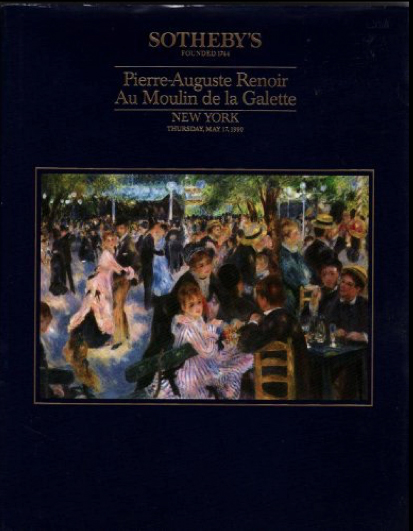

That high water mark fell again in May 1990 when van Gogh’s stunning “Portrait of Dr. Gachet” sold to the Japanese paper magnate Ryoei Saito for $82.5 million at Christie’s New York. Two days later, Saito’s designated bidder, Tokyo dealer Hideto Kobayashi, outgunned the competition again & bought Renoir’s “Au Moulin de la Galette” for $78 million at arch-rival Sotheby’s.

Saito was quoted at the time as boasting, “it’s my principle to get what I want, no matter how much it costs.”

In Wood’s brief commentary on that price, he observes, “For now, van Gogh’s record still holds but the big questions are, for how long, and who will supersede him?”

Sotheby’s 1990 Renoir catalog

Alas, Mr. Saito also suffered a severe reversal of fortune, wound up in prison for bribery and his heirs, after the paper magnate’s death in 1996, also lost control of both paintings.

The current whereabouts of Dr. Gachet and the record Renoir remain a mystery and if Dr. Gachet ever reappears at auction, a highly unlikely probability, the Dutch/German granddaughter of an earlier owner will certainly file an ownership claim against the seller.

The seasonal waves of headlines about the soaring art market crashed to a halt in November 1990 when the highly anticipated Impressionist & Modern single owner evening sale of prime French works from the estate of mega-collector Henry Ford II came on the block at Sotheby’s New York.

Thirteen of the 36 works offered failed to sell and most of the 23 that did went for prices below their low estimates.

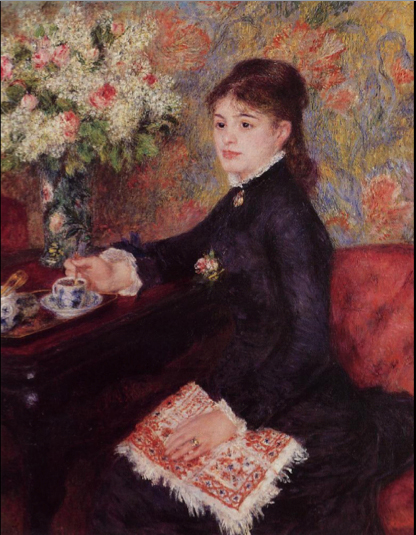

The one bright light was Renoir’s “La Tasse de Chocolate” from circa 1878 that made $18.15 million against a $15-18 million estimate.

The bad news was that Sotheby’s guaranteed a large chunk of the sale (and note the Renoir), so in turn, lost big money.

Renoir’s “La Tasse de Chocolate” from circa 1878

I’ll end my mini-recap of a bygone but still exciting period of the art market with words from a storied expert and hopefully spark further introspection and even speculation about the coming auction season.

“It was not what we anticipated,” said John L. Marion, ceo of Sotheby’s North America and the evening’s auctioneer, “the market is assessing itself, to see where we go from here—it’s quite a confusing picture.”

The above presentation was the keynote address delivered at the recent Appraisers Association of America “Of Value: 2017 National Conference” held in New York.