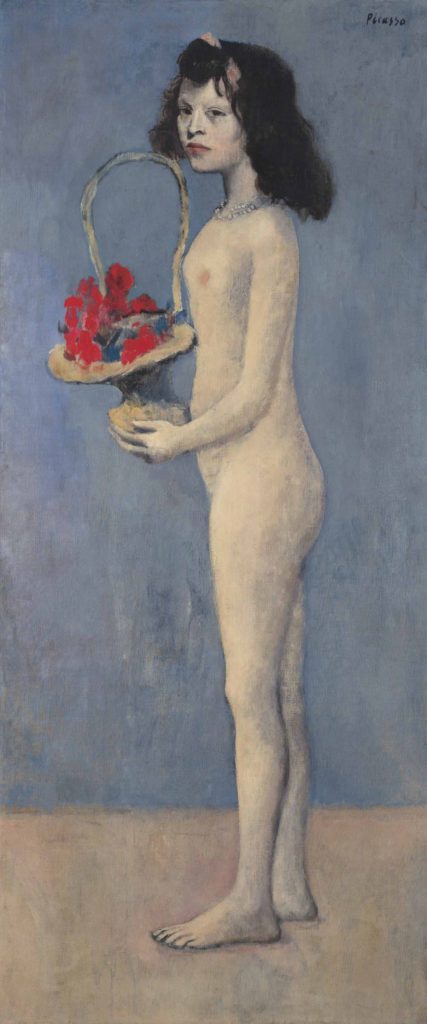

Pablo Picasso’s Fillette à la corbeille fleurie (1905) sold for $115.1 million. ©CHRISTIE’S

In 1968, David Rockefeller was part of an unusual syndicate formed by a small band of deep-pocketed collectors with close connections to the Museum of Modern Art that engineered a $6.8 million all-in arrangement with the heirs of Gertrude Stein to buy a group of artworks she had owned.

The banker, philanthropist, and statesman was the perfect candidate for the syndicate, especially since his mother, Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, was one of the founders of the museum. In addition to David, his brother Nelson R. Rockefeller was also in the elite group, along with CBS head William S. Paley, publisher John Hay Whitney, and Andre Meyer. David picked up a second chit since William A. Burden, one of the original syndicate members, dropped out.

The members met on a Sunday in December 1968 in an old Whitney wing of the museum and drew straws from a crumpled felt hat for their choices, according to a published account by David Rockefeller. David was lucky, drawing the longest straw, and chose Picasso’s stunning Rose Period flower seller from 1905 for what was then something less than $1 million dollars.

Earlier this evening, as part of the first leg of sales from the estate of Peggy and David Rockefeller at Christie’s, that painting, dating to 1905 and standing a full five feet tall, sold to an anonymous telephone bidder for $115.1 million, against a presale estimate in the region of $100 million, making it the second most expensive Picasso to sell at auction, behind Les femmes d’Alger (version ‘O’) from 1955, which sold for $179.3 million at Christie’s in May 2015.

There was a palpable feeling of anticipation in Christie’s salesroom in the lead-up to the sale. The Museum of Modern Art’s director, Glenn Lowry, was in the room, an unusual sight at an auction, and could be seen chatting with megadealer Larry Gagosian. Attendees hoping for fireworks may have been disappointed with the steady pace of the proceedings, but what the sale lacked in drama it made up for in a staggering sum: the 44 lots of 19th- and 20th-century art all sold—a rare “white glove” sale, in industry parlance—and together fetched a staggering $646.1 million.

Henri Matisse’s Odalisque couchée aux magnolias (1923) sold for $80.75 million.©CHRISTIE’S

That result easily hurdled presale expectations set in excess of $490 million (a number of the top entries were “estimate on request” lots without the usual low-to-high estimate figures) and shattered the long-standing record for a single-session, single-owner sale, set in Paris in February 2009, when Impressionist and modern art from the Yves Saint Laurent and Pierre Bergé Collection fetched €206.1, or $266.7 million. (The highest tally for any single auction session, however, still stands at $852.8 million, set at Christie’s New York in its November 2014 postwar and contemporary art sale.)

In the Saint Laurent sale, elaborately staged at the Grand Palais, a Henri Matisse painting, Les coucous, tapis bleu et rose from 1911, made top lot and a record €35.9 million (beating an estimate of €12 million–€18 million), then the equivalent of $46.4 million. Tonight, a different Matisse, Odalisque couchée aux magnolias from 1923, bested that record, bringing in $80.75 million (estimate on request in the region of $70 million).

All prices reported include the hammer price plus the buyer’s premium for each lot sold, calculated at 25 percent of the hammer price up to and including $250,000; 20 percent of that part of the hammer price that exceeds $250,000, up to and including $4 million; and 12.5 percent for anything above that.

All of the Rockefeller property was backed by a financial guarantee provided by Christie’s and a pell-mell assortment of 13 third-party backers announced by lot number only just before the start of the evening action. Remarkably, all of the proceeds from the sale, as well as from subsequent ones this week and lots sold online, will go to Rockefeller-supported philanthropies including the American Farmland Trust and Harvard University.

Ten of the 44 lots offered sold for over $15 million and, of those, seven exceeded $30 million. And seven artist records were set, led by a Claude Monet “Nymphéas” painting that fetched $84.6 million (estimate on request in the region of $70 million).

The evening got off to a fruitful start when Pablo Picasso’s exquisite and Cézanne-esque gouache and watercolor on paper Pomme (1914), originally owned by Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas and given to the couple by Picasso as a Christmas present, made $3.8 million, soaring past its estimate of $1 million–$1.5 million. Like many of the sale’s top entries, it was acquired as part of the syndicate.

Next up was Juan Gris’s Cubist-styled still life La table de musicien from 1914, executed in gouache, colored wax crayons, charcoal, and paper collage on canvas. It brought in $31.8 million (unpublished estimate in the region of $20 million). The Rockefellers acquired the painting at Parke-Bernet Galleries, a forerunner of what would become Sotheby’s in the United States, in March 1966 for $45,000.

Following the Gris was a 19th-century wild life entry, Eugène Delacroix’s magnificent and playful Tigre jouant avec un tortue from 1862, which realized a record $9.9 million (estimated at $5 million to $7 million).

Paul Gauguin’s La Vague (1888) sold for $35.2 million. © CHRISTIE’S

The price points aimed higher with Paul Gauguin’s rather radical, bird’s-eye view of La Vague from 1888, featuring a Hokusai-influenced wave, giant rocks, and two tiny figures in the Brittany surf that brought $35.2 million (estimate on request in the region of $18 million), selling to New York private dealer Nancy Whyte. It last appeared in public in 2002 at the Metropolitan Museum’s aptly titled “The Lure of the Exotic—Gauguin in New York Collections.”

A second Gauguin, more traditional ravishingly color saturated, Fleurs dans un vase, from 1886–87 and worked again from 1893–95, went to an anonymous telephone bidder for $19.4 million (estimate: $5 million to $7 million). It last sold at auction at Christie’s New York in May 2006 for $4.5 million.

Interiors and still lifes dominate the Rockefeller cache, and in stand-out fashion, as evidenced by Pierre Bonnard’s generously scaled and light-filled Intérieur (Appartement de Bonnard à Paris) from 1914 that realized $6.61 million (estimate on request in the region of $6 million).

Among the Rockefeller painterly crown jewels, Claude Monet’s cover lot, square format, and gloriously purple-hued Nymphéas en fleur (ca. 1914–1917), acquired by the art-loving couple in 1956 through Knoedler & Co. in New York, made a record $84.7 million (estimate on request in the region of $50 million). Five bidders, four of them on telephones, chased the painting in a marathon battle won by Xin Li Cohen, deputy chairman of Christie’s Asia, who was bidding for a client on the phone.

The couple benefitted in many acquisitions, including that of the Monet, from the sage advice of Alfred H. Barr Jr., the Museum of Modern Art’s brilliant founding director.

Claude Monet’s Nymphéas en fleur (ca. 1914–17) sold for $84.7 million. © CHRISTIE’S

In that same vein, the record Matisse odalisque also went to Xin’s bidder, though no paddle number was announced by ace auctioneer and Christie’s global president Jussi Pylkkänen, so one couldn’t tell if it was the same buyer of the record Monet.

Paul Signac’s sun-swept Pointillist seascape Portrieux La Comtesse (Opus no. 191), from 1888, brought a rather anemic $13.8 million (estimate on request in the region of $20 million). The couple acquired the painting at Parke-Bernet Galleries in 1957 for $31,000.

Signac’s mentor, Georges Seurat, made a bigger splash with La rade de Grandcamp (Le port de Grandcamp) from 1885 that sold to Gary Tinterow, director of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, seated in the front row of the salesroom, for a seeming bargain at $34.1 million (estimate in the region of $40 million).

Buttonholed on the stairway outside the salesroom, Tinterow would only say, “We did not buy the painting for the museum.”

When the Rose Period Picasso came up, Pylkkänen opened bidding at a breathtaking $90 million and jogged along at $2 million increments until the hammer fell at a rather disappointing $102 million, presumably just $2 million or so above the confidential third-party backer. The pale and boyishly figured flower seller, with startling dark eyes and holding up a small basket of red poppies, wears nothing but a pearl necklace. Gertrude Stein and her brother Leo acquired the work from the ne’er-do-well art dealer and former clown Clovis Sagot in 1905, for the equivalent of $30. Picasso reportedly bickered about the price but was hard up enough to accept his measly share. The picture was last seen in New York at the Museum of Modern Art’s exhibition “Masterpieces from the David and Peggy Rockefeller Collection: From Manet to Picasso” in 1994.

(Speaking of Manet, as in Édouard, his small jewel-like still life Lilas et roses from 1882, no bigger than a sheet of typing paper, went to yet another telephone bidder for $13 million, topping an estimate of $7 million to $10 million.)

Less known but thoroughly rare and unquestionably top-rated, Armand Seguin’s Les delices de la vie (ca. 1892–93), a stunning four-panel screen in oil on canvas and laid down on board, depicting a rather hedonistic dance hall scene, sold for a record $7.7 million (estimated at $1 million to $1.5 million) to Geneva-based art adviser Thomas Seydoux.

Exiting the ticket-entry-only salesroom, Seydoux described the painting as “a wonderful piece, really rare and of a high quality that’s hard to find.”

He was less impressed with the overall tenor of the auction, noting, “It seemed lacking in fire power. There are great results on paper but it was a bit slow”—a sentiment shared by several other expert observers.

After the sale, Christie’s specialist Marc Porter read a statement from David Rockefeller, Jr., on behalf of his extended family. “We are now very well on our way to achieving the goal our parents set for their philanthropic legacy,” Porter channeled Rockefeller, “and we are eagerly looking forward to what the rest of this historic week will bring.” The Rockefeller cavalcade continues throughout the week, including Wednesday evening’s Art of the Americas auction.