Kerry James Marshall, Past Times, 1997, acrylic and collage on canvas, sold for $21.1 M. – COURTESY SOTHEBY’S

A few lots into Sotheby’s evening sale of contemporary art earlier on Wednesday night, the African-American artist Kerry James Marshall’s masterful and brilliantly narrative painting Past Times from 1997, a work included in his recent and celebrated retrospective, fetched a staggering and record-breaking $21.1 million (est. $8 million–$12 million). The new record swamps Marshall’s previous mark of $5.04 million set at Christie’s New York last November for Still Life with Wedding Portrait from 2015.

It may not have been the top lot, but the Marshall was a high point of a sale that was a big win for Sotheby’s after its less-than-stellar result at Monday’s Impressionist and modern evening sale. The huge sum achieved—$284.5 million, including fees—also further burnished the contemporary category as the global art market’s favorite hunting ground. Only two of the 49 lots offered failed to sell for a razor-thin buy-in rate by lot of four percent, and the total result was on the high end of the presale estimate of $207.7 million to $285.6 million. (Estimates do not include the buyer’s premium; the hammer total was a buoyant $246.3 million.)

Although the result for the various owners-portion of the evening trailed last May’s $319.2 million total for 48 lots, led by Jean-Michel Basquiat’s record shattering Untitled from 1982 that sold to Yusaku Maezawa for $110.48 million, 40 of the 46 lots that sold this time around made over a million dollars and of those, seven exceeded $10 million—and, remarkably, 11 artists’ world auction records were set, 15 if you include those for specific mediums (a Mark Rothko work on paper, a Picasso ceramic, a David Hockney work on paper, an Agnes Martin work on paper). Ten lots were backed by financial guarantees, with four backed by Sotheby’s and six backed by third-party backers who placed so-called irrevocable bids.

All prices reported include the hammer price for each lot sold plus the buyer’s premium, calculated at 25 percent of the hammer price up to and including $300,000, 20 percent in any amount in excess of that and up to and including $3 million, and 12.9 percent for anything above that figure.

The auction began with a separate and super-charged single-owner sale of 26 lots from the Palm Beach–based modern and contemporary art collection of Morton and Barbara Mandel that was 100 percent sold, giving it white glove status and realizing $107.8 million including fees. That boosted the overall evening result to $391 million.

The Mandel lots got off to a bang—throughout the evening it felt as if the room wanted to spend money and plenty of it—with a bidding battle between one anonymous telephone and London dealer Alan Hobart of Pyms Gallery who fought over Pablo Picasso’s unique, 11-inch-high painted ceramic sculpture of an owl, La Chouette en Colere from 1953. It eventually sold to the telephone bidder for $2.5 million (est. $800,000–$1.2 million).

Mark Rothko’s vibrantly colored late abstraction, Untitled from 1969, led the Mandel cache. It sold to a telephone bidder for a whopping $18.8 million (est. $7 million–$10 million). New York art adviser Mary Hoeveler was the underbidder. Donald Judd’s tall, ten-unit Untitled stack relief in brass and acrylic sheets from 1993 sold to another anonymous telephone for $8.1 million (est. $7 million–$10 million), and Roy Lichtenstein’s Surrealist-influenced Still Life with Head in Landscape hit $10.5 million (est. $7 million–$10 million).

Other Mandel highlights included the cover lot, Joan Miró’s large-scale and expressionist-styled late abstraction, Femme, oiseau from 1969–74, that sold to another telephone bidder for $9.3 million (est. $10 million–$15 million) and Willem de Kooning’s mid-scale and lushly painted abstraction, Untitled VI from 1980, executed in a torrent of ribbon-like colors. It sold to Hoeveler for $11.2 million (est. $8 million–$12 million).

Sculpture also played a strong hand as evidenced by David Smith’s widely exhibited, 10-foot-high Land Coaster in painted steel from 1960. Set on a pair of industrial-strength wheels, it looked as if it was ready to roll. It sold to another telephone bidder for $6.7 million (est. $3 million–$4 million).

The Mandels acquired nearly all of the works through the Pace Gallery in New York in the 1980s and 1990s in a kind of extended solo gallery shopping spree; for the most part the pieces had never before appeared at auction. The proceeds from the sale will benefit the Mandel Foundation.

That wasn’t the only charity portion of the evening. Directly after the Mandel White Glove performance came a select group of five works donated by five standout artists of color being sold to benefit the new Studio Museum in Harlem building designed by Sir David Adjaye. (The five pieces were part of a much larger contingent of 37 works contributed by artists that will be offered in Sotheby’s day sale on Thursday.)

Mark Bradford’s all-over, richly layered, multi-media abstraction, Speak, Birdman from 2018 went for $6.8 million (est. $2 million–$3 million); Njideka Akunyili Crosby’s figuratively styled, mixed-media, and collage on paper, Bush Babies from 2017, brought a record $3.4 million (est. $600-800,000); and Glenn Ligon’s appropriated, text-based composition, Stranger #86, executed in oil stick, coal dust, and gesso on canvas from 2016, sold to film producer/art adviser Stavros Merjos for $2.3 million (est. $1 million–$1.5 million).

New York art adviser Todd Levin was the underbidder on the Ligon, and it was also hard to miss hip-hop recording artist Swizz Beatz (Kasseem Dean) bidding and Instagramming from the front row of the salesroom and winning Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s figurative painting, An Assistance of Amber (2017) for $555,000 (est. $100,000–$150,000).

All in, the Studio Museum of Harlem raised a hearty $16.4 million.

In the various-owner main event, which felt like the third act of a very long but occasionally entertaining play, Barkley L. Hendricks’s stunning, six-foot-tall 1974 portrait painting Brenda P. sold for a record $2.2 million (est. $700,000–$1 million) and Rudolf Stingel’s 2006 photo-realist-styled self-portrait, Untitled (Bolego), 2006, went to a telephone bidder for $4.5 million (est. $1.8 million–$2.5 million).

But things really heated up when the Kerry James Marshall painting, Past Times, sold for a record $21.1 million. Unrestrained applause greeted the sound of Oliver Barker bringing down the hammer. New York/London/Hong Kong dealer David Zwirner, who shows Marshall’s work, was the underbidder

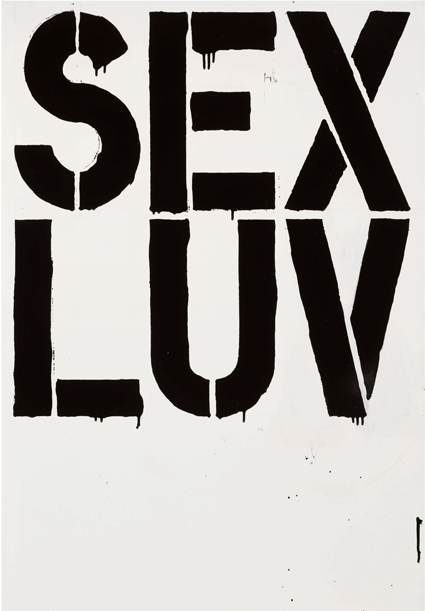

Christopher Wool, Untitled, 1992, enamel on aluminum, sold for $7.9 M. – COURTESY SOTHEBY’S

Five lots later, Christopher Wool’s medium scaled text painting, Untitled (S69) from 1992 in enamel on aluminum—the boldly lettered and slightly dripping words “SEX LUV” consumed most of the picture plane—squeaked by, thanks to its irrevocable bid, for $7.9 million (est. $7 million–$10 million). It last sold at auction at Phillips de Pury New York in May 2012 for $4 million. Another irrevocable bid-backed entry, Gerhard Richter’s magisterial, squeegee-applied Abstraktes Bild from 1991, sold to another telephone bidder for $16.6 million (est. $15 million–$20 million).

In terms of Abstract Expressionism, the cover lot Jackson Pollock, Number 32, 1949, which delivers a blazing pastiche of incendiary markings executed in oil, enamel, and aluminum paint on paper mounted on Masonite, sold to a telephone bidder for the long evening’s top lot at $34 million (est. $30 million–$40 million). Both rare to market and remarkably fresh-looking, the all-over, poured painting was harbored in the same private collection since 1983 and never before offered at auction. It was included in Pollock’s important one-man show at Betty Parsons Gallery in 1949, and it is in the artist’s catalogue raisonné, providing an iron-clad provenance sure to calm any counterfeit-fearing bidder (as all bidders should be these days). Other Ab-Ex entries included Barnett Newman’s darkly radiant Galaxy, also from 1949, which, thanks to its irrevocable bid, made $9.9 million (est. $9 million–$12 million).

David Hockney, Pacific Coast Highway and Santa Monica, 1990, oil on canvas, sold for $28.4 M.- COURTESY SOTHEBY’S

David Hockney’s large, cinematically-scaled, day-glo, eye-squinting vista Pacific Coast Highway and Santa Monica, from 1990, which hit the market fresh from a world-hopping Hockney retrospective that landed at Tate Britain in London, the Centre Pompidou in Paris, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, is the kind of undulating panorama the Hockney market pines for. It came backed with an irrevocable bid, and sold to a telephone bidder for a record $28.4 million (est. $20-30 million).

In a brief feel-good moment, Alexander S.C. Rower, Alexander Calder’s grandson and president of the Calder Foundation, nailed the winning bid for Calder’s circa 1932 Double Arc and Sphere, which was being sold by the Berkshire Museum in a controversial deaccession, for a bargain $1.2 million (est. $2 million–$3 million).

“The Calder Foundation is going to restore it and then begin to show it, so Calder’s genius will be seen by more people,” Rower said.

One of the highest prices in the sale came from an artwork that caused a pre-auction kerfuffle. There’s nothing quite like a New York Post tabloid headline (“Basquiat Bawl”) to wet or kill the appetite, as evidenced by the swirling controversy over Jean-Michel Basquiat’s stunning, four-panel word gram, Flesh and Spirit from 1982–83, executed in oil stick, gesso, acrylic, and paper on canvas. It sold to a telephone bidder for $30.7 million (estimate on request in the region of $30 million).

After the painting was consigned to Sotheby’s from the estate of Dolores Ormandy Neumann, who acquired the work from the Tony Shafrazi Gallery in SoHo in 1983 for approximately $15,000, widower Hubert Neumann went to New York State Supreme Court to challenge the sale, claiming he had been illegally disinherited from his wife’s estate and that his art gallerist daughter Belinda went behind the family’s back to convince her then terminally ill mother to will 80 percent of the painting to her. The court rejected his claim for an injunction.

“The price was O.K.,” said retired dealer Tony Shafrazi as he exited the salesroom, “but it should have been more. There doesn’t seem to be any bearing on history or value.” Shafrazi originally exhibited the work in the “Champions” exhibition in 1983. He added, “The market has its own mind.”

Though a rousing success, the sale fueled some frustration. “Real collectors can’t get in,” said seasoned Miami collector Martin Margulies, as he headed to the bank of elevators, “you just can’t compete with the global billionaires.”

The evening action resumes on Thursday with a double-header of postwar and contemporary art at Phillips and Christie’s.