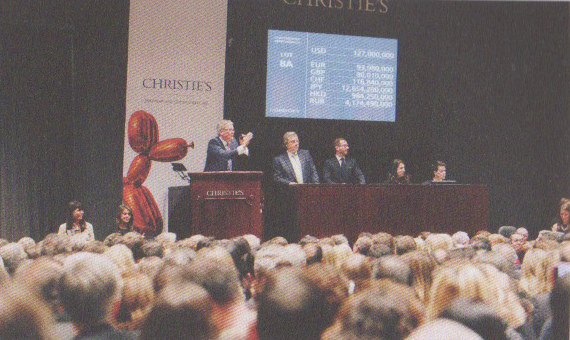

The record hammer price of $127 million ($142.4 million with buyer’s premium) is achieved for a painting on 12 November 2013

When auctioneer Jussi Pylkkänen navigated the record-smashing $495.021,500 Post-War and Contemporary art evening sale at Christie’s New York in May 2013, it seemed improbable at best that an even higher sum would be achieved just six months later, and then again in May 2014.

That November evening, Francis Bacon’s iconic triptych Three Studies of Lucian Freud from 5969 sold to the Acquavella Galleries for an astounding $542,405,000, the highest price achieved for any work of art at auction.

Freud, outfitted in a white shirt with rolled-up sleeves and tight pants that show patches of bare skin from his shin, appears uneasy under Bacon’s penetrating gaze. The fact that they were fast friends at that time, only later to become permanently estranged, added to the emotional intensity of the grand, three-panel composition, set behind glass.

Bidding opened at a stratospheric $8o million and quickly broke the hundred-million-dollar mark, escalating in five-million-dollar increments with bids from the floor and the long banks of telephones. It finally hammered at $127 million (before the buyer’s premium).

The auction of Francis Bacon’s Three Studies of Lucian Freud, 1969, oil on canvas, November 12, 2013, Christie’s, New York

The price of the Bacon eclipsed nineteenth- and earlier twentieth-century masterworks, including Edvard Munch’s The Scream from 1895, which had sold at Sotheby’s New York in May 2012 for a record $119,922,500; Pablo Picasso’s Nude, Green leaves, and Bust from 1932, which had sold fora record $106,482,500 at Christie’s New York in May 2010; and Vincent van Gogh’s Portrait of Dr Gachet from 1890, which had fetched a record $82.5 million at Christie’s New York in May 1990.

That high-water mark for Dr Gachet held its own until May 2004, when Picasso’s Garcon a la Pipe from 5905, sold from the collection of Mr and Mrs John Hay Whitney, became the first one-hundred-million-dollar painting to sell at auction, realizing $104.2 million at Sotheby’s New York.

During the bid- and record-busting sale at Christie’s in November 2013, other records were set as well, including Jeff Koons’s Balloon Dog (Orange) sculpture from 5994-2000, which brought $58,405,000, and Christopher Wool’s boldly graphic text painting, Apocalypse Now from 1988, which went to the Van de Weghe Gallery for $26,485,000. It crushed the previous E4.9/$7.7 million Wool high set at Christie’s London in

February 2012.

The Bacon triptych that evening in November 2013 was one of three lots exceeding $50 million, while eleven made over $20 million and sixteen hurdled over $1 million.

Remarkably, or so it seems in retrospect, a decade earlier, the November 2003 evening sale at Christie’s in that same category made a then respectable $62 million. It was led by Mark Rothko’s darkly luminous abstraction, Untitled from 1963, which sold for $7,175,500. Alexander Calder’s sixteen-foot-high painted metal stabile, Untitled from 5968, made a then record $5,831,500.

Six months later, in May 2004, Sotheby’s Post-War and Contemporary evening sale broke the one-hundred-million-dollar barrier for the first time.

Fast forward again to the same Rockefeller Center salesroom in May 2014 and witness Pylkkänen’s third consecutive record-breaking sale in New York for any category, this time achieving a massive $744,944,000 for the sixty-eight lots that sold. Sitting across from Pylkkänen over lunch the next afternoon, I could tell that the strenuous evening had taken a temporary toll on Christie’s president of Europe, most apparent in his English accented voice, which had an unusually raspy edge to it. After ordering a bowl of carrot soup to soothe his scratchy throat, Pylkkänen began to analyze the previous evening’s results, taking pains to emphasize the rational movement behind the sky-high figures.

‘There’s been a real consolidation and acceptance of the price levels set in May 2013 and that became a kind of jump-off point to where we are now. You can tell by the depth of bidding for masterworks in subsequent sales that collectors have grown to become very comfortable at those levels’ For those unfamiliar with Pylkkänen’s fast-paced yet meticulous auctioneering style, the newcomer’s seemingly easy-going delivery masked a tensile like strength in both strategy behind-the-scenes knowledge of both the artworks and potential bidders, even the ones screened behind the telephones. That style had been exclusively in evidence at the major London auctions until November 2012, when he took over the gavel in New York from Christopher Burge, Christie’s star auctioneer who commanded the Manhattan sale rooms with extraordinary élan for some twenty-three years.

That recent May evening with Pylkkänen on the rostrum was also a statistician’s dream, with eleven works selling for over $2o million, and of those, five made over $4o million each. Ten artist records were established, and among that cavalcade, Joseph Cornell’s extraordinary and patently surreal Medici Slot Machine from 5943 — a wood box construct ion comprised of glass, printed paper, including the reproduction of Pinturicchio’s Portrait of a Young Boy of circa 1495-1500, collage, metal, mirror and Marbles— sold for $7,781,000 (estimate $2.5-3.5 million). It was from the estate of the late and great Chicago collecting couple Edwin and Lindy Bergman, who made major gifts to the Art Institute of Chicago during their lifetimes.

Another standout from the Bergman trove was Alexander Calder’s fantastic hanging mobile, Poisson Volant (Flying fish) from 1957, which Made a record $25,925,000 (estimate $9-12 million). The evening was builtin part on such estate collections and other rare-to-market works, such as Jean-Michel Basquiat’s Untitled from 5985, featuring a crowned, nude warrior figure armed with a sword and arrows and set against a blazing orange and yellow background branded with Basquiat’s unique street language and scrawl-like mark making.

It fetched $34,885,000 (estimate $20-3o million). The late Washington-area collector Anita Reiner acquired the painting in 1982 from the Annina Nosei Gallery in New York, the dealer who first launched Basquiat in SoHo.

Another Reiner estate offering, Robert Gober’s ghostly, twenty-inch high sculpture, The Silent Sink from 1984, handmade in plaster, wire lath, wood and semi-gloss enamel paint, sold to George Economou Collection curator Skarlet Smatana for a record $4,197,000 (estimate $2-3 million). Like many other works in the sale, the Gober sink carried world-class museum credentials and had been included in the 2007 Gober retrospective at the Schaulager in Basel. Going through the alphabet of blue chip masters, Joan Mitchell’s large-scale, lyrical and colour-charged Untitled canvas from 196o, the year she permanently settled in France, sold for a record $11,925,000 (estimate $6-9 million). It also became the most expensive work sold at auction by a woman artist.

Barnett Newman’s iconic abstraction, Black Fire I from 1961, a majestic, one-hundred-and-fourteen-by-eighty-four-inch painting that had been on extended loan at the Philadelphia Museum of Art from 1985 to 2054, sold for a record-shattering $84,165,000 (estimate on request), literally doubling the Newman record.

The anonymous seller acquired the painting from London’s Mayor Gallery in 1975 for around$15o,000— no doubt a whopping sum at the time and barely a year after it had sold at Sotheby’s Parke Bernet in New York for $95,000, according to gallery owner James Mayor, who sold the painting to the consignor.

The fact that the owner harboured the painting in a great American museum for so many years and allowed it to be loaned in major exhibitions around the globe certainly burnished its allure in this market’s deep-pocketed quest for unassailable quality.

The epoch-making evening for acquiring masterpieces at massive prices was not restricted to just pretty pictures. This was evidenced by ‘s four-panel Race Riot from1964, based on an appropriated black-and-white photograph taken in Birmingham,Alabama in1963 by Charles Moore during the height of the civil rights movement, and featuring a defenseless black man being attacked by two police dogs.

Jussi Pylkkänen

It is widely considered the most politically charged subject among Warhol’s Death and Disaster paintings and was included in the Warhol retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in 1989, two years after the artist’s death. It sold to the Gagosian Gallery for $62,885,000 (estimate on request). The sixty-by-sixty-six-inch acrylic and silkscreen ink on linen last sold at Christie’s New York in November 1992 for $570,000 (estimate $600-800,000); it was obviously a very different point in time for the art market.

The May 2054 auction was a signature, double-feature evening for Warhol. The twenty-by-sixteen-inch White Marilyn from 1962 was also on sale, signed by the artist and dedicated to his then dealer Eleanor Ward of the Stable Gallery to mark his first solo New York show there in November r962, where identically sized works of the screen goddess in different background colours were on offer at $250 apiece.

The petite painting ignited a bidding war that went on for almost ten minutes. At $34 million, and after agreeably splitting a bid from one of the tenacious telephone bidders, auctioneer Pylkkänen broke the tension with a deadpan question, ‘Would anyone else like to come in?’, causing laughter and a much needed jolt of energy to keep the room humming. It helped drive the final price skyward to $41,045,000 (estimate $12,8 million).

‘The reality of the art market today’, said the auctioneer, ‘is that the new buyers are buying art based on the quality of the artist and the importance of the work. It’s all about masterpieces because the masterpieces can engage people from across the globe. What we’ve seen in the last few years, particularly in the American artists of the 195os and 1960s, they’ve become global painters in a way that Picasso and Monet were: Remarking on how fast this post-war market has moved, Pylkkänen observed, ‘I remember a year ago, there were six works or so that sold for over twenty million dollars during the week of Post-War and Contemporary sales. As the auctioneer, I wondered when a work at twenty million came up, how many bidders I would have. That no longer goes through my mind.’