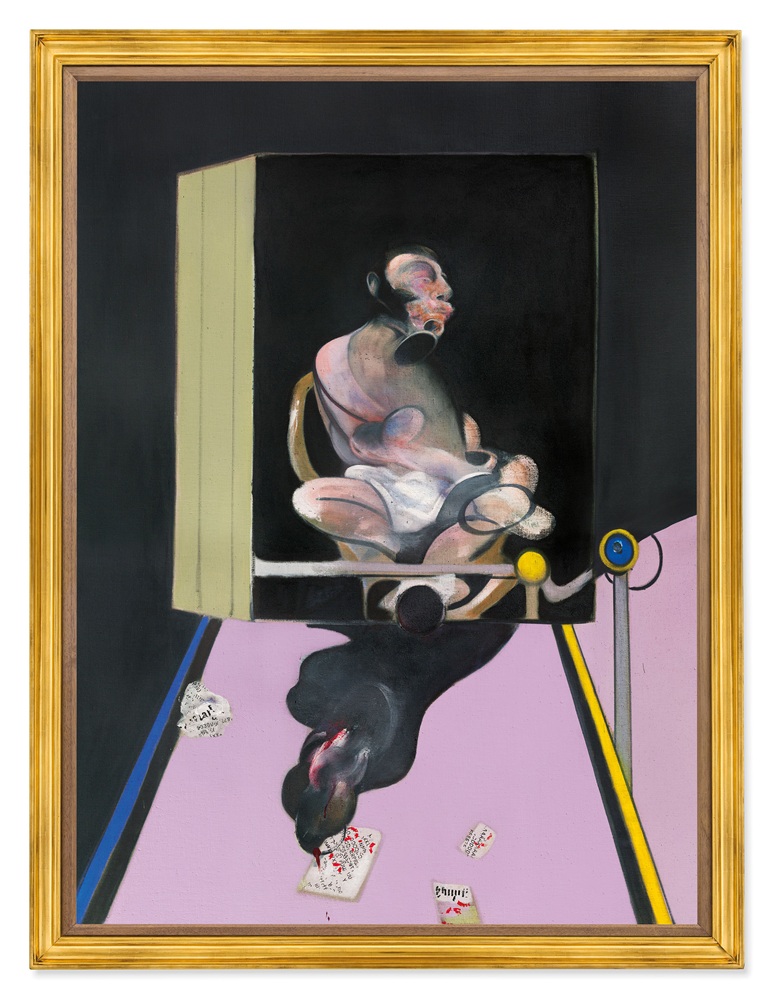

Francis Bacon, Study for Portrait, 1977, oil and dry-transfer lettering on canvas, sold for $49.8 million. COURTESY SOTHEBY’S

Anchored by a powerful Francis Bacon cover-lot portrait, Christie’s closed the season’s evening auctions in New York on Thursday night with a postwar and contemporary art sale in a subdued room that nevertheless brought in a strong $397.1 million, reaffirming its standing as the market leader over its arch-rival Sotheby’s.

The tally, including fees, surged past the auction’s $320 million presale low estimate, but Christie’s didn’t provide a high estimate for comparison, due to five lots being “estimate on request” as well as a general lack of transparency. Six of the 64 lots offered failed to sell, for a trim buy-in rate by lot of 9 percent, and the total hammer was $343.5 million.

Tonight’s result, including fees, trailed last May’s more robust $448 million sale over 68 lots, led by Cy Twombly’s Leda and the Swan (1962), which fetched $52.8 million.

Forty-eight of the 58 offerings that sold this evening made over a million dollars and of those, seven sold for over $15 million. Better yet, seven artist records were set.

A huge number of lots were backed by guarantees—37 lots from third parties and five from the house. In all, then, 42 of the 64 offerings had financial backing, assuring success.

(All prices reported include the hammer price plus the buyer’s premium, which is 25 percent of the hammer up to and including $250,000, 20 percent on that part of the hammer above $250,000 and up to and including $4 million, and 12.5 percent for anything beyond that number.)

The evening began with a bang, as David Wojnarowicz’s apocalyptic, four-panel spray paint and stencil composition, Science Lesson (1982–83), featuring a flotilla of floating figures and houses in space and armed soldiers racing across volcanic ground with a view of Earth burning in the distance, sold to a telephone bidder for a record $708,500 (est. $400,000-$600,000).

It was followed by the calming presence of David Hockney’s floral still life, Antheriums (1995), which sold to another telephone bidder for $5.6 million (est. $2.5 million–$3.5 million). The Hockney last sold Christie’s New York in May 2004 for $875,500.

In that same decorator vein, Francois-Xavier Lalanne’s uber luxe The Mayersdorff Bar (1966), commissioned by a Belgian client and crafted in maillechort, steel, brass, copper, and blown glass, sold to a telephone bidder for $4.57 million (est. $2.2 million–$2.8 million). It came backed with a third-party guarantee and last sold at Sotheby’s Paris in November 2010 for €384,750.

Auctioneer Jussi Pylkkanen, who is Christie’s global president, admonished Alex Rotter, co-chairman of Christie’s postwar and contemporary art, for texting during the bidding battle, of which he was a part, something like a parent might do to a distracted teen.

Back to painting: Christopher Wool’s large-scale, monochrome abstraction, Untitled (P563), 2008, composed in enamel on linen and bearing successive and deliberate revisions, sold to a telephone bidder for $8.26 million (est. $7.5 million–$9.5 million). It also came to market with a third-party guarantee.

Abstraction was in keen demand as evident in the results for Joan Mitchell’s stunning, roughly 80-by-60-inch oil on canvas, Blueberry (1969), which made a record-shattering $16.6 million (est. $5 million–$7 million), and for Morris Louis’s Devolving composition (1959–60), mural-scaled at 68 by 100 ¼ inches, which sold to yet another telephone bidder for a record $5.71 million (est. $5 million–$7 million). New York dealer Jonathan Boos was the underbidder on the record Mitchell.

Those figures paled next to the sum paid for Mark Rothko’s monumental, wall-power abstraction, No. 7 (Dark Over Light), 1954, which appeared in his traveling 1971–72 retrospective, shortly after his suicide at age 66. It sold to a telephone bidder for $30.7 million (estimate on request in the region of $30 million).

The Rothko sold at Christie’s New York in November 2007 for $21 million and this round marks the fifth time the approximately 90-by-60-inch work has appeared at auction. This time it was backed by a third-party guarantee and seemingly needed the backing.

Of the half-dozen casualties, a fresh-to-market Clyfford Still, harbored in the same collection since 1978, PH-916 (1946-No. 1), 1946–47, darkly luminous and color saturated with palette knife strokes, failed to find a buyer at a chandelier bid of $14 million (est. $15 million–$20 million).

Willem de Kooning’s late and spare Untitled VII (1986), brawnily scaled at 77 1/2 by 88 inches, sold to New York and London dealer Per Skarstedt for $5.94 million (est. $4 million–$6 million). It last sold at Sotheby’s New York in May 2011 for $4.28 million.

“We had a show in London of late de Koonings six months ago,” Skarstedt said right after the auction, standing outside Christie’s Rockefeller Center headquarters, “and I’ve been buying late de Koonings for the last few years. It made about the same price tonight as it did seven years ago. I hope they’ll go up eventually.”

There was also high-end action on the figurative painting front, with Francis Bacon’s searing and iconic cover lot, Study for Portrait (1977), bearing a ghostly likeness to the artist’s lover George Dyer who committed suicide in October 1971, two days before the opening of Bacon’s career defining-retrospective at the Grand Palais in Paris. It sparked a bidding battle between a trio of telephone bidders, finally going down at a hammer price of $44 million ($49.8 million with fees) against an estimate on request in the region of $30 million.

The seller acquired the painting from Marlborough Gallery in Vaduz, Lichtenstein, in May 1977, at a time when his paintings were selling for under $50,000 at auction. Market intel suggests the painting arrived at auction after making the rounds on the private market for a long stretch.

“It’s a really strong price and a very good subject,” said London dealer and Bacon expert Pilar Ordovas as she exited the salesroom, “but the subject [George Dyer] simply isn’t enough, as we know.”

Ordovas was referring to the fact that other Bacon portraits of Dyer have fetched as much as $70 million at auction, which is what Portrait of George Dyer Talking (1966) made at Christie’s London in February 2014. Still, tonight’s Bacon ranks as the highest-priced postwar and contemporary works of the season.

The work is based on a studio photo by John Deakin in which Dyer is seated bare-chested in his white undershorts, his head swiveled to one side as if avoiding the gaze of the viewer. Bacon never painted from life, always from photographs.

Other figurative entries included Kerry James Marshall’s portrait of a goddess-like nude, with a cryptic reference to Roy Lichtenstein’s famed Girl with Ball (1961). You Must Suffer If You Want to be Beautiful (1991), executed in acrylic, graphite, crayon, paper collage, and printed paper collage on canvas sold to New York art adviser Jamie Frankfurt for $2.29 million (est. $2 million–$3 million).

Nicolas de Stael’s nu Debout (1953) made a record $12.1 million (est. $7.5 million–$9.5 million) and came to market with a third-party guarantee. It last sold at Artcuriel in Paris in June 2013 for €4,690,690 and tonight’s figure literally doubled that result.

Painted in a prime year but otherwise unexceptional, Jean-Michel Basquiat’s Red Rabbit (1982), authenticated by the now-disbanded Basquiat authentication committee, sold to the telephone for $6.61 million (est. $5 million–$7 million). It was in sharp contrast to the brilliant Basquiat, Flexible (1984), which sold at Phillips an hour or so earlier for $45.3 million.

Pop Art was also in the long queue, headed by Andy Warhol’s disaster series silkscreen, Most Wanted Man No. 11, John Joseph H., Jr., a 1964 diptych sourced from a post office wanted poster that sold to a telephone bidder for $28.4 million (est. on request in the region of $30 million). Once owned by saloon keeper Mickey Ruskin of Max’s Kansas City fame, it was last at auction at Sotheby’s New York in May 1992, selling for $577,500.

Another prime ‘60’s Warhol, Double Elvis (Ferus Type), 1963, standing tall at about 80 by 50 inches, with the faint after-image of the gun-slinger crooner in the immediate background, sold to Brett Gorvy of the New York/London dealership Lévy Gorvy for $37 million (est. on request in the region of $30 million). It last sold at Sotheby’s New York in May 2012 for the exact same price of $37 million, after which it was acquired by the now-embattled casino magnate Steve Wynn, who offloaded the picture tonight.

How could such a major painting by a revered artist stay dead flat over six years?

“It’s on holiday for the moment,” quipped dealer and Warhol maven Alberto Mugrabi as he left the salesroom. (A market footnote: Mugrabi underbid Basquiat’s Flesh and Spirit, 1982–83, which sold for $30.7 million at Sotheby’s on Wednesday evening.)

In a lighter-hued and sun-splashed offering, Richard Diebenkorn’s magisterial and very California Ocean Park #126 (1984) sold to Gorvy for a rousing and record-shattering $23.9 million (est. $16 million–$20 million). It was one of a dozen Diebenkorn works in the evening sale, all of them backed with third-party guarantees and sold by the Donald and Barbara Zucker Family Foundation to benefit its program. All in, the Diebenkorn group made $43 million.

On the sculpture front, Jeff Koons’s mountainous mound, Play-Doh (1994–2014) in polychromed aluminum and bearing an impressive resemblance to the kind found in kids’ playrooms, sold to dealer Larry Gagosian for $22.8 million (est. on request in the region of $20 million). The elaborately fabricated sculpture, measuring 124 by 152 ¼ by 137 inches is one of five unique versions, of which another was included in the artist’s 2014 retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art.

Of a very different sort and concept, a Robert Gober masterwork, Untitled, from 1993–94, comprised of an amalgam of bronze, wood, brick, aluminum, beeswax, human hair, and chrome-plated bronze, as well as a recycling water pump, sold to Andrew Fabricant of Richard Gray Gallery for a record $7.29 million (est. $6 million–$8 million). Looking down at the grated floor piece, you see evidence of a human figure and wonder just how it got there.

“It’s a fabulous piece and I was glad to get it at that price,” said Fabricant as he headed toward the exit. Stopping in mid-stride, the dealer added, “I don’t understand the momentum of these sales, the energy in the room changes from day to day and it’s completely bi-polar.”

Fabricant was referring to the relatively low and almost vacant energy in the Christie’s salesroom, despite the strong numbers being rung up—an atmosphere that was the complete opposite of the stadium-like excitement at Sotheby’s on Wednesday.

That conundrum can be considered until the next round of auctions in London this summer, which will offer the next opportunity to try to gain a realistic grip on the state of the art market.