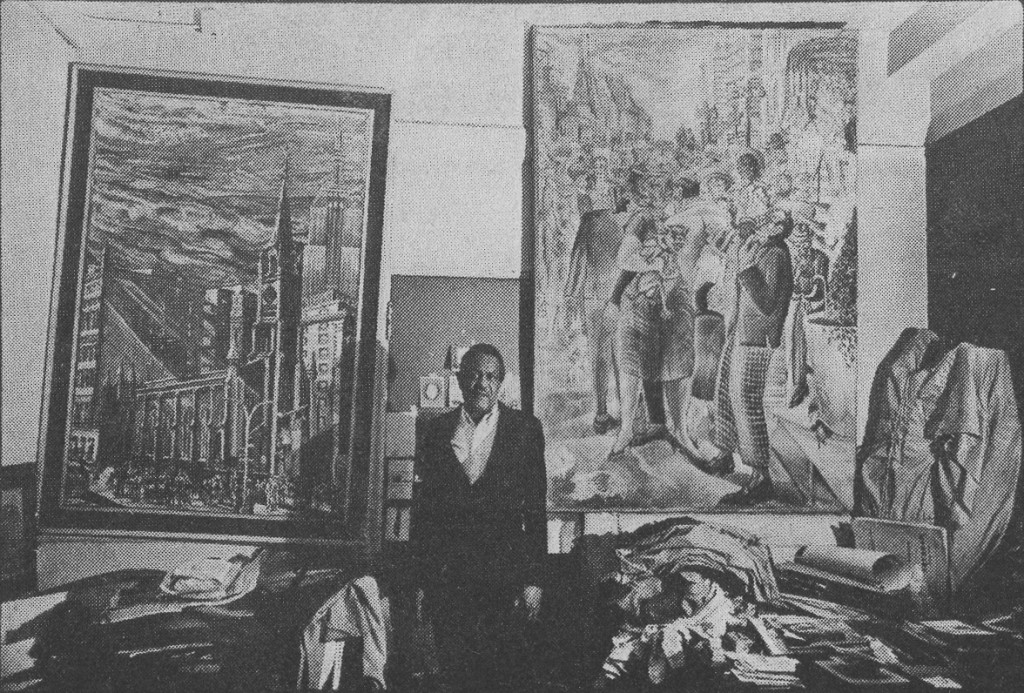

Joseph Delaney, photo by George Malave

Though their paths have frequently crossed, two New Deal-WPA vets, Joseph Delaney, 74, and Herman Cherry, 69, had never met until this year when they were both chosen as CETA artists in New York City’s Cultural Council Foundation’s painters pool.

Delaney is a figurative painter. Cherry is a non-objective painter. Both men studied under Thomas Hart Benton at the Arts Students League in the early 1930’s before getting jobs with the WPA Federal Art Project. Cherry worked in Los Angeles, Delaney in New York City. The two artists shared similar berths as easel painters and as assistants on large mural painting projects.

In California, Cherry did drawings forGordon Grant’s mural for a post office inVentura. Delaney assisted Edward Laning at the WPA mural studio at Pier 72 at 33rd Street and the Hudson River. The famous four—panel mural, Story of the Recorded Word, resides on the third floor of the New York Public Library on Fifth Avenue and 42nd Street.

Interviews with the artists in theirstudios, surrounded by their art and memorabilia (such as the rare colored drawing by David Smith inscribed to his friend Cherry, “Labor Day at Herman’s House,” 1960) created a galloping journey into the past. In 1937, according to Delaney, George’s Bar on 7th AVenue and Barrow St., was the “Studio 54 of that day.” Tales of poetry readings in MacDougal Alley behind the Whitney Studio Club on East 8th Street and 24 hour cafes like the Waldorf on Sixth Avenue produced a dizzying mix of social art history. Remarks on the WPA and CETA tumbled into the microphone of the tape cassette recorder like a staccato montage of images from the 1930’s to the 1970’s.

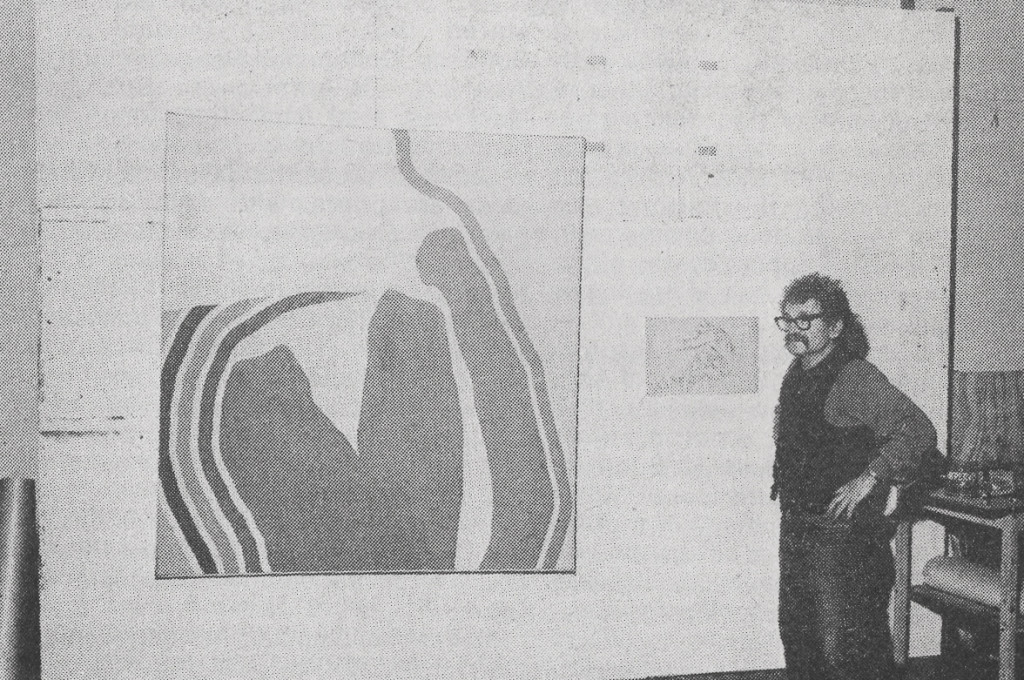

Herman Cherry, photo by Sarah Wells

PINK SLIPS & PEWTER

From an easy chair in his studio-living space in a loft building on Union Square West, Delaney recalled the early days of the New Deal and credited Roosevelt’s Brain Trust for sparking the government’s first cultural experiment with creative artists. “We worked 15 hours a week for $23.60. It was later raised to $27.50. My first assignment was at the Children’s Playground on 134th and 5th Avenue under the Children’s Aid Society. Later, I was transferred to the Synder Avenue Boy’s Club in Brooklyn. There were always unpredictable shakeups in the art project because of political involvements. Some politicians wanted to destroy the program and both sides compromised. I got my share of pink slips—five of them—but each time I came back to different departments.”

The pink slip Delaney referred to was a bureaucratic device to cut down the bulging work relief rolls after a WPA-er had 18 months of work. A fellow black artist, Jacob Lawrence got one of the infamous slips and never returned to theproject. Delaney did not want to talk about Lawrence because it reminded him of “swimming in troubled waters.”

Delaney said his most fascinatingassignment was at the Metropolitan Museum, working on the Index of American Design. “I worked with Paul Revere silver and pewter, Early American Dutch textiles, Steuben glass. We had to copy it by hand from the cases in the American Wing. It required exact precision and our copy was a little better than a photograph. It proved to be great training. I’m very happy for that.”

The 74-year-old painter who still goes to the Art Studenta Leauge every day to draw, spends four days a week at the Henry Street Settlement Arts for Living Center on Grand Street in the Lower East Side. During a recent visit to the landmark settlement house, I found Delaney in a sun splashed studio, putting some finishing brushstrokes on a small acrylic and charcoal study of a dramatics class. His CETA assignment is to document the artistic activities at the center—from art classes to dance to live performances. “As soon as the snow leaves I’ll get my portable easel and do up a canvas job.”

“The people at the settlement are most cooperative in every way. They make me feel more like an artist than I’ve ever felt before. They are ahead of most places. They know what atmosphere an artist needs. This is an ideal place for creative arts. It’s like a dream to be here. There’s so much freedom, I’m afraid of it.”

SYNCHRONISM & THE 5 SPOT

Herman Cherry tears the cellophane wrapper off his Dunhill panetela, inspects the product and says, “I’ve been sort of the problem child of CETA because of my background in various areas of art teaching for 35 years or so, writing for arts magazines, writing poetry. I’ve been painting all my life. So, they have wanted to put me in a particular position. My concern was possibly to work at home which is what we did in the WPA. I know CETA isn’t set up for that. They’ve been trying to get a mural for me and there’s a possibility for that at the NYU Graduate Center on 42nd Street.

Cherry, whose slides have been enthusiastically received at the Graduate Center describes his painting style as “non-objective—far out abstractionist or whichever way you want to put it.” When asked the obvious question about comparing WPA and CETA, he said it was too early to tell. “I don’t know enough about CETA yet. I don’t think anyone does. It has to be judged by the type of work that is produced.

During the eight years of WPA/FAP from 1935-43 (according to statistics dug up by art historian Francis V. O’Connor) over 2,500 murals, 17,000 sculptures, over 100,000 easel paintings, 11,000 fine prints, 22,000 Index of American Design plates and 35,000 posters were executed to the fiscal tune of approximately $35 million.

At this point in the interview, Cherry disappeared from the kitchen table at his Mercer Stret loft in a cloud of cigar smoke to retrieve 1974 issue of the American Art Review, specifically, an article on the WPA by art historian, David M. Sokol. Sokol’s piece, in part, focused on the unanimous opinion of WPA artists that the programs were administered on the local level by bureaucrats who had little or no idea of how artists worked or how to evaluate the art produced. Cherry sees this as a potentialproblem for CETA. “Bureaucrats simply don’t understand that there has to be a pliability—all artists work differently. Some start at 9 AM and work to 5 PM. I know some artists who don’t do anything for a couple of weeks—they just simmer—arid then they will work 24 hours a day. It comes to a fruition, finally. In the end, no matter how much you struggled with it you want it to look easy-relaxed, like a Matisse painting.”

Cherry worked from 1934 to 1939 on the WPA/FAP. He described some of the community art centers and galleries (from Wyoming to Mississippi) that were started in this period and hopes that CETA, with its national network of artists, will start similar centers and become a continual exhibition place for new art. Five little museums, one in every borough, could start up (watch out New Museum, here comes the Little Museum), each reflecting the particular mix of ethnic groups and neighborhood cultural flavors. For his community work, Cherry would like to do five metaphorical paintings representing each borough.

The painter, who in the early 1950’s was credited along with his good friend, sculptor, David Smith, with turning an obscure music joint on the Bowery into the internationally acclaimed Five Spot, who’s been written about in John Gruen’s avant-garde art chronicle of the 1950’s and early 1960’s—”The Party’s Over Now”—thinks it’s ridiculous that unknown CETA artists should be worried about copyright and ownership at this point. “There were no grumblings in the WPA about who owned the paintings. We were absolutely delighted that the government got our work.”

Cherry, who first studied in California under Stanton MacDonald Wright (a major retrospective on Synchronism and American Color Abstraction which S.M.W. co-founded with Morgan Russell is currently at the Whitney Museum) has a humidor full of art anecdotes that flutters from Al Leslie packing his pick-up truck with artists from the Cedar Bar and delivering them to the doorstop of the Five Spot to Benton at the Art Students League, showering his 21-yearold student with vibrations of worldliness (Benton had lived in Paris

with S. M. Wright) and Renaissance inspired teachings.

“BIG HIPPED WOMEN”

Joseph Delaney remembers riding down Fifth Avenue on a double-decker bus with Reginald Marsh after a class at the Art Students League. A small framed pencil portrait of his classmate, Jackson Pollock (before he lost all his hair) sits in a crowded corner of his studio—which in itself is a documentary on canvas of artist life in New York City. “At that time you could raise Hell anywhere you chose. New York City was open 24 hours a day. Fourteenth Street never closed down, river to river. Now those big iron gates that come down after dark weren’t there at the time. Life was different then.”

“Marsh visited me at my studio once. I remember one thing he said—why do you make em so damned hard to look at? He didn’t make em too easy to look at either, but we both shared the same interest—big hipped women.” A smile (river to river) broke out over the painter’s face and his eyes which have soaked in 49 years of Bohemia life in the Village lit up like the Brooklyn Bridge at night.

“I’m the oldest guy on the job,” Delaney mischievously admitted, “and it’s my responsibility to be as candid as I can. In time CETA will turn into something the community can count on and the artist can rely on. The need today is greater than it was during the Depression. You’ve got to give creative people support—there are more artists per capita now. You’ve got to keep our

culture alive.”