photo: Kristine Larsen

One of Jean Pignozzi’s many web sites summarizes him as an “Italian, Harvard-educated venture capitalist.” But that barely scratches the surface. The tall and imposing 60-year-old, heir to an automotive fortune, is a dynamo in the worlds of art, design, and fashion and a widely published photographer with four books to his credit, most recently the .loo-page Catalogue Deraisonne, published by Steidldangin in 2010. Like their predecessors, the hefty black-and-white tome has a diaristic slant, with pictures of his glamorous and mostly ultrarich friends (Carla Bruni, Keith Richards, Jack Nicholson, Diane von Furstenberg) cavorting at chic places around the world, including Pigozzi’s own Villa Dorane on Cap d’Antibes. The publication occasioned a 2010 exhibition—bearing

the mock-exasperated title “Jean Pigozzi: Johnny STOP!” —at the Madison Avenue venue of his friend and dealer Larry Gagosian. One of the most compelling images captures art world royalty at leisure in 1991: Gagosian, Charles Saatchi, and Leo Castelli, all in beachwear,casually conferring in a handsome interior (on St. Barthelemy, the title informs us). Queried about their friendship, Saatchi playfully told Art+Auction,” I love Johnny Pigozzi very deeply and wish he could become my next bride.”

The high-energy collector and jet-set photographer talks about what makes him run… and run.

There are a lot of Johnny Pigozzis,” says Daniel Wolf, the New York–based collector and private photography dealer who has known Pigozzi for 30 years. “There’s the collector, there’s the businessman, there’s the socially important person, all of those things, but way down deep, he’s really an artist.” Pigozzi the photographer, Wolf adds, is “consciously documenting an extremely important aspect of the one percent, and it’s great that he’s doing it because in a voyeuristic way you can see what it’s like.”

Those pictures seem to crop up everywhere. In 2008 the Helmut Newton Foundation in Berlin staged “Pigozzi and the Paparazzi,” an exhibition conceived by June Newton, Helmut’s widow, and curated by Matthias Harder, which drew a distinction between the celebrity stalking immortalized in Fellini’s La Dolce Vita and Pigozzi’s insider approach of snapping famous friends. Works by Erich Salomon, Weegee, Tazio Secchiaroli, and Ron Gaiella established the professional context. Last November another exhibition drawn from Catalogue Deraisonne— this one called “Pigozzi, Stop! You’re Too Close”—opened at the Multimedia Art Museum in Moscow, prompting Pigozzi to enthuse, “I’m very honored, because this is not a private gallery or something, this is a serious state museum.”

Perhaps the interest in Pigozzi’s photography can hest be measured by the prices his work commands. Last year he donated a photograph capturing Mick Jagger in performance to the American Foundation for AIDS Research (AMFAR) charity auction conducted by Simon de Pury during the Cannes Film Festival. “When I asked Johnny before the auction what price he’d be happy with,” recalls de Pury,” he said, Maybe €15,000.” The picture sold for €300,000 ($428,000).

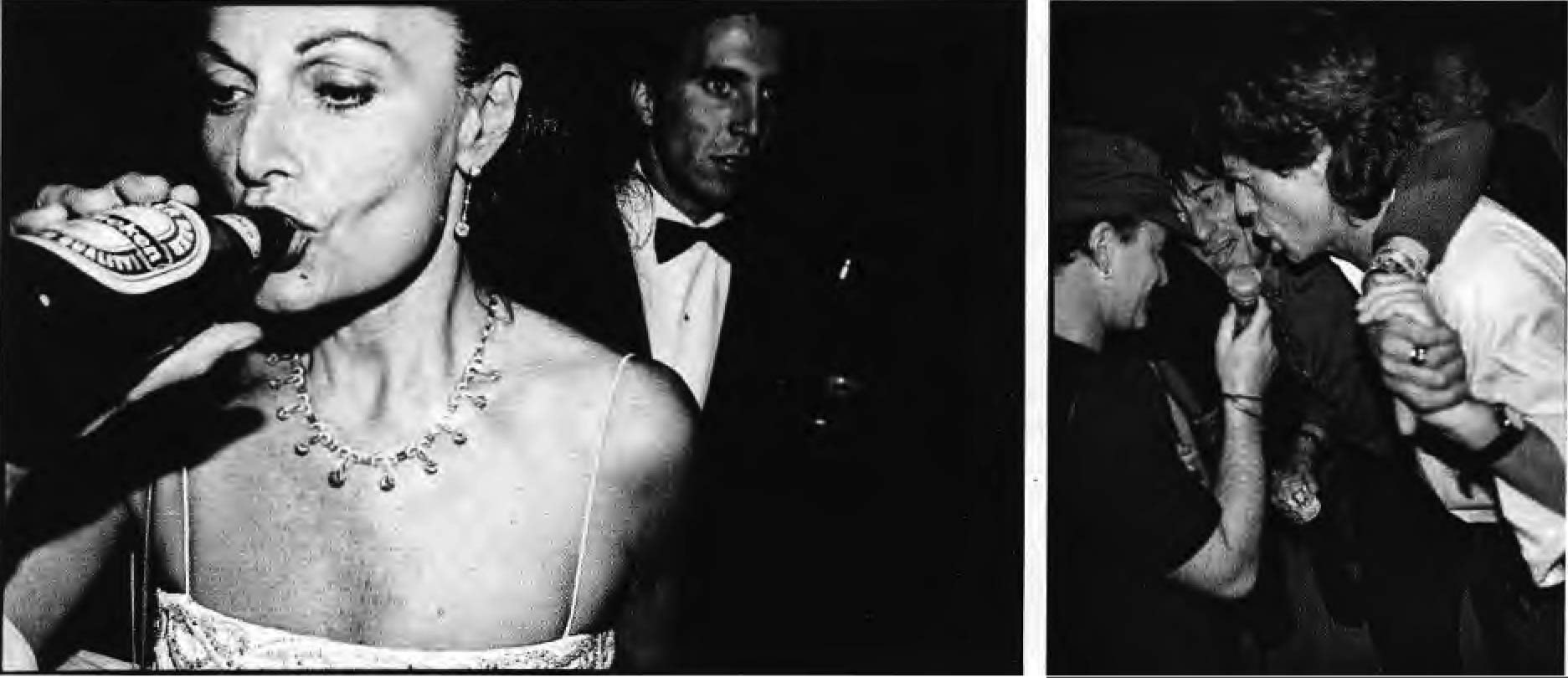

Photographs by Jean Pigozzi: Diane Von Furstenberg, Venice, Italy, 1991, left, and Bono, Ron Wood and Mick Jagger, Mick’s Birthday Party, Villa Dorane, Antibes, France,1999, from Catalogue Déraisonné, 2010.

Filling a large easy chair in his sprawling, Ettore Sottsass–designed triplex in the Hotel des Artistes, just off New York’s Central Park (Sottsass also designed or supervised the interiors of his Paris, London, Geneva, Panama, and Riviera residences as well as his boat, the Amazon Express), Pigozzi reflects on his near compulsion for collecting all sorts of things, including a great deal of contemporary African and Japanese art. “I had a collection like a good dentist from Cincinnati,” recalls Pigozzi of his early efforts as a collector of contemporary art. “A little Clemente, a little Basquiat, a little Warhol, a little Sol LeWitt—but it wasn’t interesting.Then I became friends with Charles Saatchi, and he said,`This is stupid. What are you doing?'”

Asked if anything in his family background had contributed to his insatiable collecting, Pigozzi was dismissive:”Zero. My parents had a typical collection of nouveau riche, bourgeois art—a couple of Renoirs, a couple of Sisleys—and they had their apartment in Paris, but it was a bad version of Versailles. I have no idea where this comes from, but it’s a disease, and I know I caught it when I was very young. As a kid I collected stamps, pebbles on the beach, anything. I liked to have at least zo of something.”

“I had a collection like a good dentist from Cincinnati”

In 1989 Pigozzi viewed “Magiciens de la terre” at the Centre Pompidou and the Grande Halle at the Parc de la Villette in Paris. Organized by Jean-Hubert Martin, the controversial exhibition showcased loo artists from around the globe and was conceived as an alternative to the prevailing “colonialist” view of non-Western art. Pigozzi saw “a few African things that completely blew my mind.”There were startling Expressionist paintings by Cheri Samba, delicate drawings by Frederic Bruly Bouabre, fantastic architectural models by Bodys Isek Kingelez—all so contemporary in feeling, says Pigozzi, that they”could have been done in Brooklyn or Berlin.”Wanting to buy them, he tracked down Andre Magnin, the French curator who had overseen the African art portion of the Paris exhibition. An intense collaboration between the collector and the expeditionary talent scout began and has continued for 23 years.

Art world interest has grown with the collection. In 2005 the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, staged “African ArtNow: Masterpieces from the Jean Pigozzi Collection,” comprising 94 objects by some 33 artists from 15 sub-Saharan African nations. The exhibition traveled to the National Museum of African Art in Washington,D.C. Today Pigozzi’s holdings of more than 6,000 objects, officially known as the Contemporary African Art Collection, is largely harbored in a storage facility in Geneva.

Ironically, he has never set foot in Africa. ” I’m a spoiled and impatient traveler,” he admits. “Down there you can spend hours in customs, hotels are not so great, and you can get sick from the food.” But this hasn’t impeded his feel for talent from that continent. In 1999 he encountered two uncredited photographs from Bamako, Mali, in “Africa Explores,” an exhibition curated by Susan Vogel at the New York Center for African Art. Excited by the Irving Penn–like grace of the black-and-white studio portraits,Pigozzi faxed the images from the catalogue to Magnin in Paris and asked him to find the photographer. After three or four days searching, Magnin located an old man seated on a huge metal trunk in a tiny storefront in Bamako. It was Seydou Keita, and the trunk contained approximately 6,000 of his negatives, dating back to the late 194os. For decades, KeIta’s portrait business was based on clients renting costumes and props, both Western and African, for formal shots. According to Pigozzi, Magnin persuaded Keita to release a hundred or so negatives (the New York Times reported a significantly higher figure in an article by Michael Rips published in January 2006). He took them back to Paris, “where we cleaned them up and made some beautiful prints,” Pigozzi says.

It was the beginning of Kelta’s ascent. In 1997 he was included in “Amours,”an exhibition at the Fondation Cartier pour Part contemporain, in Paris, and had his New York debut at the Gagosian Gallery in SoHo, where the larger-format prints sold for up to $16,000. Six years later, works by Keita and fellow Bamako photographer Malick Sidibe, a talent Pigozzi had pursued at Keita’s urging, were featured in the two-person exhibition “You Look Beautiful Like That” at the National Portrait Gallery in London. But after Keita’s death in Paris, in 2006, a nasty and lengthy legal dispute erupted between his heirs and Pigozzi and Magnin over possession of the photographer’s negatives and charges of fake signatures on the prints. Defending his actions, Pigozzi told Rips in 2006 that without his efforts, Keita “would be totally forgotten.”Today he remains steadfast in that claim:”I am incredibly proud that I made this immense talent the most important photographer in Africa. I think he’s on the same level as Irving Penn or Avedon.”

Pigozzi’s acquisitive eye shifted to Japanese contemporary art in 2006, when he visited his friend Takashi Murakami’s one-day Geisai artfair in Tokyo. Some of the fruit of that initial field trip was on view last year in Japan Congo,”an exhibition selected from Pigozzi’s African and Japanese holdings by the Belgian artist Carsten Holler, which opened at Le Magasin, in Grenoble, and traveled to the Garage Center for Contemporary Culture, in Moscow, and Milan’s Palazzo Reale.

Pigozzi surveys his New York domain, flanked by, on his right, Tom Sanford’s The Defosition, 2003, and, on his left, two untitled paintings with collage from 2008 by Pathy Tshindele. Photographs by Malick Sidibé line the shelf below. Maurizio Cattelan’s customized shopping cart piece, Less than Ten items,1997, is parked nearby. photo: Kristine Larsen

“I keep on collecting African art,” explains Pigozzi,” but I’ve built a huge collection of very young artists from Japan, born mainly after 1980.” Asked about his seemingly contrarian decision to pursue Japanese art while ignoring the skyrocketing values of Chinese works, Pigozzi concedes that “financially, I should have focused on China because the market is two times bigger than Japan’s, and for some reason few galleries outside of Japan have been interested in showing contemporary Japanese art, apart from Murakami and Nara. So I don’t think the Japanese art is an investment.” Attraction is what drives him.”I like what’ see now in China, but I think the Japanese are a step ahead into craziness and weirdness. I go to galleries there that are the size of a New York elevator, and every time I’m surprised by the amazing things I find. 1 realty hope I’ll be able to promote some of these artists, to show their work in the West.”

As for other facets of his wide-ranging holdings, Pigozzi regrets he didn’t collect more work by Basquiat when he knew him in the early 1980’s. He has one painting from those years, for which he paid $2000, and he says ruefully,”I was an idiot because I didn’t appreciate what a huge talent he was.” Then again, this collector isn’t into blue-chip. “I feel when you walk into somebody’s apartment on Fifth Avenue or house in Malibu and you see a Basquiat,a Warhol, a Richard Prince, you say to yourself,’Seven hundred thousand dollars, $2.2. million, $350,000…’To me that is completely uninteresting. I’d rather go to a house where there’s great art and I have no idea who the work is by.” Pigozzi jokes that he could go to Larry Gagosian and a few other galleries with $20 million and decorate his apartment, “but that doesn’t excite me.” Instead, he says, “the paintings I buy for $1,000 or $2,000 could be famous in a hundred years.I don’t think I’m going to change my focus.”

Queried about his plans for the thousands of artworks he owns, the collector says, “I’d love to open a private museum in Paris, London, or New York, but I don’t have the money.If I were Bill Gates or Paul Allen, the first thing I would do is build a museum.” Pigozzi pauses fora moment, then acknowledges,”It’s really another obsession: WhatcanIdo with all of this stuff?”