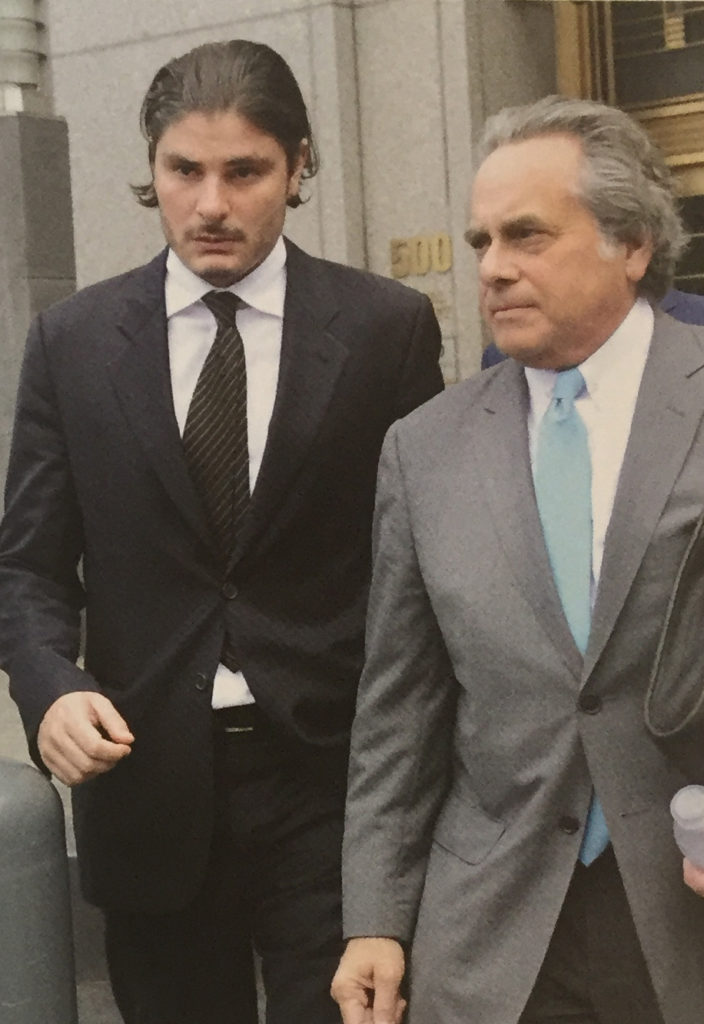

Hillel Nahmad, left, exiting Manhattan federal court on April 17 with his attorney Benjamin Brafman. Photo: Louis Lanzano/AP/CORBIS

After a Gambling Indictment, Is It Business As Usual?

In April, 34 people were charged with illegal gambling activity in a wide-ranging federal indictment. Among them was Hillel “Helly” Nahmad, the 34-year-old scion of the global art-dealing family and principal of an eponymous gallery in Manhattan’s Carlyle Hotel. In the wake of the front-page headlines that followed, concerns were raised in the art world that the Nahmads’ guarded empire might be compromised.

Though Nahmad’s father, David, wasn’t charged or explicitly named in the 84-page indictment—he was referred to only as “Nahmad’s father” and described as a “billionaire art dealer located in Europe”—he was alleged to be one of the backers of the illegal enterprise, dubbed by federal prosecutors the “Nahmad-Trincher Organization.” The indictment further alleged that the organization obtained “at least $50 million” from racketeering and money-laundering activities.

Benjamin Brafman, an attorney representing Hillel Nahmad, said there was “no truth whatsoever to the allegation that the Nahmad family art business or the Helly Nahmad Gallery had any role in financing the gambling operations referenced in the indictment. Any suggestion to the contrary is patently false.”

After prefacing his remarks by saying he couldn’t comment on the substantive charges against his client, Brafman added, “I have no doubt that both the Nahmad family art business and the Helly Nahmad Gallery [which remained open at press time] will continue as very successful and well-respected operations for many years to come.”

The Nahmad art business started humbly in Italy during the early 1960s, when David and his younger brother, Ezra, began working for their older brother, Giuseppe “Joe” Nahmad, trading modern masters from de Chirico to Picasso, shuttling between Paris and Milan before establishing their New York gallery in the 1970s.

The family currently operates three galleries. Two are in New York: Helly Nahmad Gallery and Nahmad Contemporary; the latter, run by David’s younger son, Joseph, opened in May at 980 Madison Avenue with a group of recent paintings by Sterling Ruby. The third is Helly Nahmad Gallery, London, where Ezra Nahmad’s son, also named Helly, runs an elegant Cork Street space.

Last November, in a different kind of blow to the close-knit family, Giuseppe Nahmad died in Monte Carlo at the age of 80. “Joe in essence,” said a source close to the family, “developed the model of wholesale in the high-end art business by buying cheap—and holding—works of art and reselling them at auction. It was unprecedented and obviously very successful.”

That buy-and-hold philosophy, assiduously followed by the brothers and their progeny, has produced an inventory of more than 4,500 artworks—including some 300 Picassos—valued in excess of $3 billion overall. It is cloistered in a duty-free facility at Geneva International Airport. Despite the spate of unwanted publicity and a death in the family, the Nahmad ship is still afloat and, in fact, appears to have plenty of wind in its sails. That much was evident at Art Basel in June, when the Helly Nahmad Gallery in New York sold Alexander Calder’s large red mobile Sumac, 1961, for a price in the region of $12 million, It also sold a trio of white paintings by Lucio Fontana, priced between $2 million and $6 million each, according to the gallery.

Soon afterward, during the London auction season, two guaranteed paintings from the Nahmads were cover lots at Impressionist and modern evening sales at Christie’s and Sotheby’s. Both were widely recognized as Nahmad property, having been shown at the Kunsthaus Zurich as part of the Nahmad Collection exhibition in 2011-12, and both sold quickly: Wassily Kandinsky’s early Studie zu Improvisation 3, 1909, brought £13.5 million ($21.1 million) at Christie’s, and Claude Monet’s Le palais Contarini, 1908, commanded £19.6 million ($30.8 million) at Sotheby’s. Another Nahmad picture from the Kunsthausexhibition, Amedeo Modigliani’s Portrait of Paul Guillaume, 1916, also sold at the Christie’s evening sale, for £6.7 million ($10.6 million).

When asked about these sales amid the scandal, a source at Sotheby’s commented, “We are aware of the situation and without saying more, we are very scrupulous in these matters. We felt there was no exposure selling [the Monet and other Nahmad-held works] under the ordinary terms of passing good title.” A spokesperson at Christie’s offered a similar boilerplate assurance, stating, “We do not comment on individual clients or their business transactions. Christie’s is fully conscious of its legal obligations and has thorough policies that are strictly applied to all those participating in our sales.” Christie’s also provided the relevant paragraph from its Anti-Money Laundering & Regulatory Authorities notice, which applies to all clients.

Salvador Dali’s La musique (also known as L’orchestre rouge or Les sept arts), 1957, consigned by the Nahmads, sold this past June at Sotheby’s London for $7.8 million.

Less-visible Nahmad entries that week included Salvador Dali’s La musique or L’orchestre rouge or Les sept arts, 1957, which sold for £5 million ($7.8 million) at Sotheby’s, and Henry Moore’s unique 8-foot, 8-inch-high granite Stone Form, 1984, which found a buyer at £1,405,875 ($2.2 million) at Christie’s. The Nahmads had acquired the Moore sculpture at a Christie’s London auction in June 1993 for £47,700 ($72,000), illustrating the family’s acumen in timing sales to reap big profits.

“People bid enthusiastically on their stuff,” said David Norman, worldwide co-chair for Impressionist and modern art at Sotheby’s, referring to the Nahmad properties in the London round of auctions in June. “Nobody shunned them, and there was plenty of reporting that it was theirs.”

“Everyone always thinks they have masses of B-grade stock, which they do,” added Norman in describing the Nahmad holdings. “But, as is evident in their exhibition catalogues they’ve held on to a lot of terrific things.”

“Museum loans to one gallery were withdrawn, reportedly in response to the publicity.”

Norman was referring in part to the Kunsthaus exhibition and also to the more recent exhibition of some 45 Picasso paintings from the Nahmad Collection at the Grimaldi Forum in Monte Carlo, where the venue is observing the 40th anniversary of the artist’s death.

“If you’re going for a great Picasso exhibition, it’s not,” said Norman, “but a lot of things I know were bought by them on the reserve or bought post sale, look a lot better now, and look like smart buys. They were better-quality pictures than they looked hanging at Christie’s or our place.”

Still, a source close to the Nahmad family told Art+Auction that in the midst of Art Basel week, David Nahmad made a quick trip to Monaco after press reports that the principality, in which legal gambling is a major revenue generator, was considering canceling “Picasso dans la Collection Nahmad” at the Grimaldi Forum because of the gambling scandal association. The dealer apparently succeeded in extinguishing resistance to the exhibition, and it opened as scheduled on July 12.

Another exhibition, “Collection David et Ezra Nahmad: lmpressionnisme et audaces du XIXe siècle,” at the Musee Paul Valery in Sete, France, with 70 works by artists from Pierre Bonnard to Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, opened as scheduled on June 29.

The family had already canceled a Monet-Richter exhibition that was supposed to have opened in May at the Helly Nahmad Gallery in New York after several museum loans were withdrawn, reportedly as a result of the publicity surrounding the arrest and indictment of the gallery’s proprietor.

Apart from that canceled exhibition, evidence of a dip or ding in the Nahmad art business appears to be negligible. “As far as their own business is concerned,” says David Nash, a principal of Mitchell-Innes & Nash gallery and former longtime head of the Impressionist and modern department at Sotheby’s, “I don’t think there’s been any change. I would say it’s pretty much business as usual.”

Veteran New York dealer Richard Feigen concurs with Nash and others. “I don’t think it will have any effect on their art business at all. Essentially, Helly’s father, David, acquires paintings. He doesn’t really fancy selling them. He buys everything at auction, holds onto it for decades, and finally sells something at auction for many times what he paid. I’ve seen a lot of their inventory on computer, and literally it’s billions of dollars,” he says. “Once in a while, they consign us something for Basel or some other art fair, but it’s very hard. Basically David does me a favor. Clearly, they don’t have to sell a damn thing.”