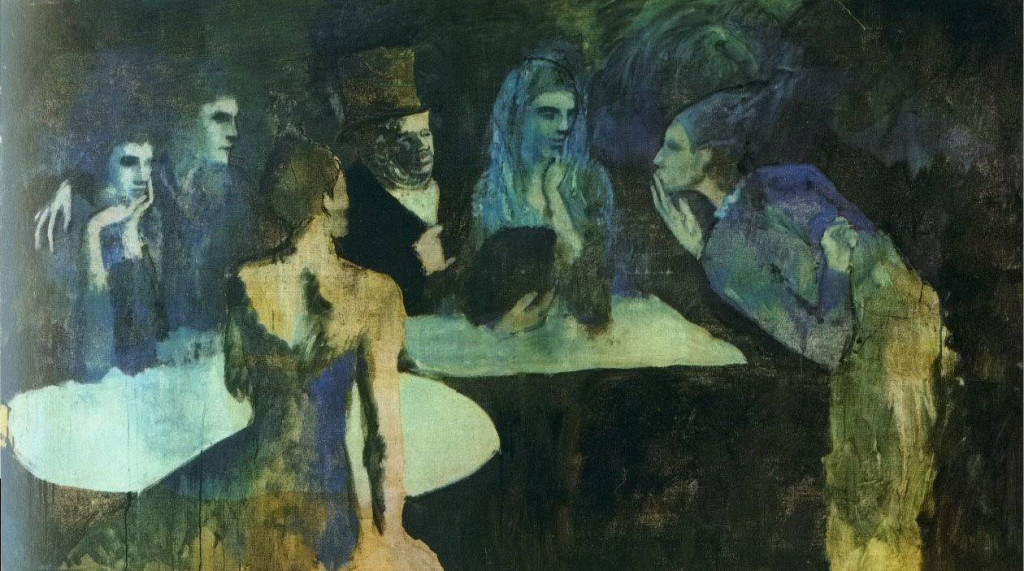

“The Marriage of Pierrette,” by Picasso (1905)

For 60 years, its whereabouts were unknown, its very existence in doubt. But last November, “The Marriage of Pierrette,” Pablo Picasso’s Blue Period masterwork, made a dramatic reappearance on the auction block and was sold by a tiny Paris auction house to a very rich Japanese buyer for a staggering $51.7 million. With that, it became the second most expensive work of art sold at auction, but the mystery of the picture was far from solved.

Unlike most major works that come to auction wearing their polished armor of provenance, “Pierrette” has no traceable exhibition history. From its shrouded beginnings in 1905 to the circumstances surrounding its miraculous reappearance on the market, the painting remains enigmatic. Before the four-minute-long sale, an eclectic cast of players fought for the picture. The French minister of culture, Interpol, a stable of lawyers, a savvy Swedish collector and a sleuthing art historian pursued the nocturnal cafe scene.

Its tangled history, full of intrigue, provides a revealing glimpse inside a secret world of buyers and sellers who are typically identified by such vague phrases as “Asian trade” or “Property of a Gentleman.” It is the story of an elite art world accustomed to doing business in its own clubby way, far from public scrutiny.

The only list of previous owners is a short one found in an early monograph on Picasso. Even the 56-page, oversize Binoche and Godeau auction catalogue prepared for the November sale doesn’t breathe a word about provenance. “Pierrette’s” only historical documentation remains a poor-quality black-and-white photograph coupled to a brief entry in that original monograph speculating that the painting was lost “and presumed destroyed” due to a dispute between unnamed heirs.

Though Picasso’s life and work have been sifted through like no other 20th-century artist, no scholar-living or dead-seems to know much of anything about the huge canvas that more resembles an abandoned sketch than a fully completed painting. But no one disputes “Pierrette’s” narrative power or originality.

One theory racing around the small elite of international dealers, auction houses and in-between players is that the painting was put up at auction “as a way of cleaning the picture,” says a Madison Avenue dealer who is familiar with the painting and the auction world. “You put it in a sale and then you can say, well, it was auctioned on such and such a date. If there was something wrong with the picture you can ask why didn’t someone do something about it when it was in the auction. Sometimes it works. Sometimes it doesn’t.”

The price achieved for Picasso’s stunning picture-just a bid away from unseating van Gogh’s “Irises” as the world’s most expensive artwork-propelled France back into the auction limelight, which had been a top priority of the minister of culture. “Pierrette” would actually have beat out “Irises” if Sotheby’s or Christie’s standard 10 percent buyer’s premium had been applied-it’s double the current French rate of 5 percent.

Until the Binoche and Godot sale, a 1917 Modigliani painting of a nude seated on a couch, “La Belle Romaine,” selling in 1987 at a now skimpy-sounding $7.5 million, was the most expensive artwork sold through a French auction house. It was part of a landmark sale of remaining masterpieces from the collection of Georges Renand, a one-time owner of the deep-blue-tinted “Pierrette.”

Another former owner of “Pierrette” was the German art dealer Hugo Perls. According to his son, Klaus Perls, a Madison Avenue art dealer, Hugo Perls purchased the painting in Paris sometime in the 1920s. “Picasso’s dealer, Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, tried to convince my father to buy cubist works but he was only interested in the Blue and Rose periods. He bought lots of pictures,” says Klaus Perls. The painting hung in the family’s apartment in Berlin until 1931 when the Perls’ marriage broke up and “the whole thing dissolved.” Hugo Perls is credited with naming the picture.

Finessing a Rediscovery

The 6 1/2-foot-wide painting was completed in Paris in 1905 when Picasso was barely 24. The cast of six ghostly figures is huddled around two cafe tables, eerily lit in a blue haze. Picasso’s harlequin-the protagonist in his famous series starring impoverished circus performers-stands in tattered tights, bowing and blowing a kiss to the beautiful veiled woman seated closest to him. Reading between the lines of the painting’s title, the puffy groom in his dented top hat is powerless to do anything about his compromised position. His right fist is clenched except for the extended thumb and pinkie, a derisive and unmistakably Mediterranean gesture for a cuckold.

In a scene that might have reminded some of “The Maltese Falcon,” Fredrik Roos, the seller last year of “Pierrette,” first saw the painting when it was “rolled up like a carpet.” Roos, 38, is a Swedish industrialist with extensive trading contacts in the Soviet Union. He is also a world-class art collector with a museum of his own in Malmo, Sweden-the Rooseum, which houses a huge and ever-growing international cache of cutting-edge contemporary works, from Jean-Michel Basquiat to Julian Schnabel.

Roos discovered “Pierrette” in a roundabout way when he was contacted by his friend, the auctioneer Jean-Claude Binoche, in 1987 about an apartment for sale overlooking the Seine. Roos went to see the flat on Quai Malasquai, which had been the home of Bernard de Sariac, a wealthy lawyer who died a bachelor in November 1986. There Roos met young Bernard de Sariac, the nephew, heir and namesake of the elder de Sariac who also practiced law, a tradition in the distinguished family. When Roos learned from the nephew that the elder de Sariac had been Paolo Picasso’s lawyer (Paolo was Pablo’s first son and died in 1975 at age 54), “I asked him if he didn’t have some Picassos. The answer was no and I had no reason to doubt that. Maybe his uncle didn’t like Picasso’s work,” speculated Roos in a faxed interview.

Roos made an offer on the apartment with its dramatic river views, but the nephew wanted more and the negotiations ended. In May 1988 Binoche called Roos again in Stockholm and said the younger de Sariac did own a Picasso and wanted to sell it quickly. Unfamiliar with the title, “The Marriage of Pierrette,” (“Les Noces de Pierrette”) Roos looked the picture up in a Picasso catalogue and found it “ugly.”

“So I called them back and said that I wouldn’t even make the trip to Paris if de Sariac didn’t cut 2 million French francs off the price. He did that, and off I went.” Roos’s opinion of “Pierrette” drastically changed when he saw the painting, and he bought it immediately. Roos says he paid “not over 20 million French francs” (approximately $3.3 million) for the painting. “I thought, even at that price, even though I’m not a connoisseur, I couldn’t go wrong. By October {of 1988} I took possession of the painting.”

Shortly after his acquisition, Roos casually notified the Moderna Museet in Stockholm (the MOMA of Sweden) of his purchase, and the dumbfounded curators hurriedly arranged for a temporary export permit to borrow the painting for their major Picasso exhibition opening that month. It was the first time the painting had been exhibited since it was completed in 1905, just two years before Picasso’s revolutionary leap to cubism. Roos had his “bargain-basement” Picasso, but without a permanent export permit the picture could not leave France, drastically reducing its salability on the world market, of late dominated by the Japanese.

Unlike the United States, France has strict export laws governing works of art or “cultural treasures.” The rarity of the artwork in question is determined by a select committee from the Louvre museum. Roos initially tried to donate 20 contemporary works, valued at $5 million, to the French, in exchange for the export license, but Minister of Culture Jack Lang wasn’t interested in the swap.

Then Roos had another idea. Another Blue Period Picasso, “La Celestine” (1904), had been exhibited with much fanfare in Paris, and it was for sale. It shared “Pierrette’s” predicament of not having an export license. Roos proposed to Lang that he would buy “Celestine” and donate it to the government in exchange for “Pierrette’s” export license. He agreed to pay “Celestine’s” owner, French dealer Didier Imbert, 100 million francs (approximately $16.4 million) and in turn gave it to the five-year-old Musee Picasso in Paris. Imbert had paid $4.5 million for the painting when he acquired it in 1987.

As Roos explained in a faxed interview from his RoosGruppen office in Stockholm, ” … I walked over to Imbert with Binoche… . After a few hours of, I must say, unusually pleasant negotiations, we had agreed. I bought `La Celestine’ and gave it away to France the next afternoon in return for the export license. Of course I reassured myself that I would get the license if I did give them `La Celestine.'” Roos said he had a further assurance that he would not have to pay for “La Celestine” until he received his payment for “Pierrette.” Picasso painted “Celestine,” his wall-eyed procuress in Barcelona, before he made his big move to Paris. Art historians claim that the nasty-looking madam with the milky eye symbolized young Picasso’s all-consuming fear of going blind from venereal disease.

“There is no precedent to this exchange-it was an exceptional measure,” explained French Minister of Culture Lang in a faxed interview. “The authorization {on Nov. 9} for the exit of `Les Noces’ against the entrance of `La Celestine’ into the National collection was the sole condition of the transaction. We were able to preserve our patrimony as well as the dynamism of the French market.”

Lang described “Les Noces de Pierrette” as a “seductive tableau but one not fully achieved… . It was less interesting on both historic and artistic levels than `La Celestine.’ ‘La Celestine’ is considered one of Picasso’s ultimate works of the Blue Period.”

For his high-stakes gamble, Roos received the export permit, opening up the marketing of the painting to a worldwide audience, namely the Japanese. At the stratospheric heights he was aiming for, few players could handle all the millions-and certainly no one in France. The relatively tiny French auction house, Binoche and Godeau, initially estimated the painting’s value at 300 million francs (at the time, approximately $46 million).

Last year, before his delicate deal with France was consummated, Roos courted Sotheby’s. “His first choice would have been to sell it outside of France in a big international auction with us in London or New York,” recalls Michel Strauss, head of Sotheby’s fine art department in London. “But without the permit, he didn’t have that option.”

When asked about the condition of the painting, Strauss chuckled and replied, “Oh no, there were no problems with it.” But “Pierrette” had been widely maligned in London and New York before the sale because of a crude attempt to remove an old film of varnish from the thinly painted canvas. A spokesperson for Binoche and Godeau complained after the sale that rumors of the painting’s poor condition had squelched any American bidding and that Sotheby’s was bad-mouthing the painting despite a condition report and certificate issued by John Bull, an internationally regarded art conservator based in London.

“I found it in excellent, practically original condition, and I gave it a clean bill of health,” said Bull in a phone interview from London. He did find fault with the recent “amateurish and clumsy” attempt to clean the picture and patch two or three tiny holes in the canvas “but that could be easily corrected.”

The Mystery of an Earlier Buyer

But what happened to the Picasso immediately before Roos bought it? Was the botched job of removing the original coat of varnish a result of a hurried transaction predating Roos?

In response to a request for an interview, a spokeswoman for Bernard de Sariac in Paris said curtly by phone, “Mr. de Sariac does not talk to journalists” and hung up. Additional attempts to reach his office were futile. But according to the dizzying report in Le Monde appearing on the day of the auction, an eleventh-hour suit was filed by de Sariac’s sister to stop the sale to Roos and freeze the proceeds. The court action failed to budge the judge, and the negative article might have scared off French bidders but certainly no one in Japan.

The article also revealed that the younger de Sariac had successfully petitioned a French court prior to this action to invalidate the sale of Picasso’s “Pierrette” by his uncle, completed just months before he died at age 85. The elder de Sariac-obviously out of touch with market conditions-had sold the picture to an “Italian-American” art dealer identified in court papers only as “Claudio S.”

Contacted by phone at his New York residence, Claudio Bruni-Sakraischir, de Chirico expert and owner of the Medusa Gallery in Rome, denied ever owning the painting: “No, no, no, I never had it.” Bruni did say he was a friend of the elder de Sariac. Subsequent attempts to interview Bruni were unsuccessful.

De Sariac argued in court that his uncle didn’t have “all his mental faculties” and that the $200,000 sale of the painting to Claudio S. should be reversed and the ownership be restored to himself as heir. De Sariac’s sister, Valerie de Sariac Goulet, used a similar argument in her suit. She said that, because of her uncle’s enfeebled mental state, he was in no condition to make her brother his sole heir.

The timing of the events leading to de Sariac’s recovery of the painting and Roos’s subsequent involvement coincided with an Interpol bulletin listing the painting as stolen, published in the International Foundation for Art Research’s monthly report of November 1987, and its subsequent “recovery” in IFAR’s July-August 1988 report.

Attempts to learn more details of the recovery through IFAR and Interpol’s office in Washington led to a phone interview with Mireille Ballestrazzi in Paris, head of the French Department of Interior’s Central Office for the Repression of Theft of Works and Objects of Art. “The painting was eventually recovered by the family but to continue to maintain there was a theft would be calumny,” she said. “It became nothing. We even solicited the help of the Americans at one point but I can’t talk about the story. It’s a story that existed but doesn’t exist anymore.”

The Latest Owner

Last October, seemingly impervious to a variety of pre-sale assaults, “Pierrette,” now outfitted in a 17th-century gilt frame, basked in the spotlight. The dead end at Interpol and the incredibly timed court decision prompted a press query to Lang as to whether the Culture Ministry had any influence over the key court decision favoring Roos. “The role of the minister of culture is to defend the patrimony without getting involved with the stories of private matters which have no solution,” responded Lang. “We only heard about the `contestation’ through the bias of the press.”

“I was amazed when I saw that tiny photograph of the painting in the IFAR bulletin,” recalled Picasso scholar John Richardson in a phone interview. “I had been desperately trying to track it down for years {Richardson is completing the first volume of the forthcoming Random House tome, “The Life of Picasso”}. It was all very vague and mysterious.”

Richardson discounts one theory that Picasso gave “Pierrette” to his son, Paolo, during World War II-perhaps to engage in a black-market sale. He says it would have been unlikely because of Paolo’s decidedly unbusinesslike demeanor. Richardson mentioned a “one-armed courtier en tableau” {art courier} named Gerard who obtained the painting from the second of two recorded owners, Georges Renand, and subsequently sold it to his friend Paolo Picasso in 1942 or 1943. De Sariac was also Paolo’s lawyer and Gerard is the last traceable link to the painting before it presumably fell into de Sariac’s hands.

Because of France’s considerable “wealth tax,” it is considered common practice for individuals to closet assets. If this is true in this case, the elder de Sariac-who also helped engineer Picasso’s breakup in 1960 with his longtime mistress, Francoise Gilot-kept the picture in storage for more than 40 years, only to unload it for a song to Claudio Bruni and his company.

Commenting on the court case, Fredrik Roos said, “A, for me, totally unknown lady was ill-advised by some French Perry Mason to take court action against me in order to frighten me to pay some ransom, if only to escape eventually damaging publicity. Neither she nor her lawyers scared me the least. One has to fight such attempts of `robbery’ otherwise one will end a pauper. Even the seller, de Sariac tried me, in vain I’m glad to say. Look, he knew more about what he was doing when he sold `Pierrette’ to me than I did.”

The controversy over “Pierrette’s” bruised provenance doesn’t end with the court suit but still reverberates as the new owner, real estate developer Tomonori Tsurumaki, president of Nippon Autopolis Ltd., prepares to unveil the painting in Tokyo, three months after the sale. Tsurumaki intends to hang the long-missing Picasso along with at least 100 primarily French impressionist works in a yet-to-be-built museum on the volcanic grounds of his Formula One international auto race course and resort on Kyushu Island in southern Japan. It is expected to open late next fall. On March 21, “Pierrette” and 40 other French paintings in the Nippon Autopolis Collection will debut at the Ohita Prefectural Museum of Art. On April 20, “Pierrette” will journey alone to the Yokohama Museum of Art for an extended visit. Any public venue is better than a bank vault.

Incredibly, or so it seems, Tsurumaki-in a public relations dream-purchased “Pierrette” on the day he announced construction of his $500 million Autopolis to a roomful of dignitaries in Tokyo. He ducked out of his gathering for the few minutes needed to bid on the painting. Slick, fold-out brochures of the futuristic-looking resort were passed out in auction salons in Paris and Tokyo moments after his winning bid was cast.

A number of high-placed auction observers speculated that Tsurumaki had no competition other than bidding against the reserve (the secret bottom-line price determined by the seller of the artwork. Anything below that price would be returned or “bought in” to the seller). The dubious practice of taking bids “off the chandelier” is by no means unique to this artwork but fueled rumors about the artificiality of the unusual morning sale, described as “a three-card monte game” by one disgruntled observer. “A lot of people suspect it was rigged-you know, pre-sold-and that the auction was just theater,” commented a jet-setting art consultant who prefers anonymity.

Not so, says Paris dealer Herve Odermatt. “I had carte blanche from my client to buy the painting but I looked at it the day before and it was a magnificent picture but the condition was not 100 percent. I stopped bidding at 290 million French francs. Already at 200 million, I was alone with the Japanese. In a normal situation, there should have been at least two or three other bidders. It was very strange … awful to just ignore New York {the sale took place at 4 a.m. New York time} and aim for the Japanese market… . I was not so sorry I stopped at 290 when the man who bought it in Japan made a declaration that he would have paid a much higher price.”

One expert from a competing auction house claimed Tsurumaki was on hand weeks before the actual sale to witness the uncrating of the picture in Tokyo, fresh off a heavily insured flight from Paris. According to the source, that first dramatic look-engineered by the ever-accommodating Binoche-sealed the picture’s foreign fate.

Asked what he had learned from his Parisian adventure, Roos responded, “I think I could set up a consultancy helping people defend their rights against all parties interested in hindering them from selling a valuable painting.”

Even with his multimillion-dollar gift to France, Roos will realize a breathtaking profit of more than $25 million.