Facing the 16th-century facade of the Catedral Metropolitana de Xalapa in the Zocalo. Mexico City’s grand central square, you feel the steady heartbeat of Mesoamerican history. The reddish-hued foundation stones of the cathedral were recycled in the first quarter of the 16th century out of the rubble of a great Aztec temple that stood near the same site in Tenochtitlan. When Cortes marveled at that great Aztec city in 1519,

Facing the 16th-century facade of the Catedral Metropolitana de Xalapa in the Zocalo. Mexico City’s grand central square, you feel the steady heartbeat of Mesoamerican history. The reddish-hued foundation stones of the cathedral were recycled in the first quarter of the 16th century out of the rubble of a great Aztec temple that stood near the same site in Tenochtitlan. When Cortes marveled at that great Aztec city in 1519,

it had already stood for more than a thousand years.

Behind the Catedral Metropolitana’s massive door are the altars and paintings of post-conquest Mexico’s rich viceregal era, the first fusion of European and Mexican art. Mexican culture spans 3,000 years—from the massive heads sculpted by the Olmecs on the southern point of Yucatan Peninsula to the saturated abstractions of Rufino Tamayo, the country’s greatest living artist. Three cities — Mexico City, Oaxaca, and Merida— provide the chance to overview the entire timeline of Mexico’s art and architecture.

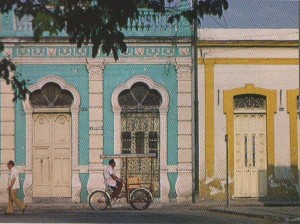

Merida, once known as the “Paris of the West;’ is still today known for its colonial architecture.

In the capital city, just across from the cathedral and excavated from beneath the cobblestones of the Zocalo, is a museum containing funerary and ritualistic deities carved and crafted in the early 1500s at the Aztecs’ Templo Mayor. The museum, opened in 1987, stands on the spot where, nine years earlier, an unsuspecting city worker jackhammered into an extraordinary discovery: the sacred precinct of the Aztecs. Serving as the dramatic centerpiece of the museum is the immense eight-ton bay relief of Coyolxauhqui (the moon goddess and sister of the Aztec war god Hu itzil Ipochtli).

Across town to the west in Chapultepec Park is a world class repository, as vast as the Louvre, the National Museum of Anthropology. There you can cover the three great periods of what is called Mesoamerican culture. The museum’s major pieces include an Olmec stone head: the 24-ton Sun Stone, an Aztec calendar; and carved limestone stelae showing Mayan rulers and historic events.

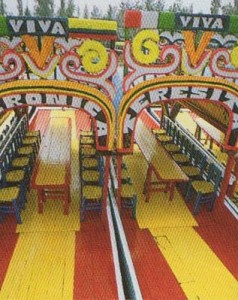

Festive gondola-like boats in Mexico City’s floating gardens of Xochimilco, not far from a museum that holds a world-class collection of paintings by

Rivera and Kahlo.

The Aztecs, much as the Romans did with the Greeks. incorporated into their capital city the pre-Columbian cultures that preceded them. Their sophisticated city planning of and architecture in Tenochtitlan owes much to the Toltec city Teotihuacan, once the greatest metropolis of ancient North America, and already deserted by the 15th century.

Thirty miles northeast of Mexico City, Teotihuacan flourished from approximately 100 A.D. to its mysterious decline and abandonment in the middle of the 8th century. Today, the Avenue of the Dead has been excavated nearly- intact, with the steep Pyramids of the Sun and the Moon at either end.

Back in Mexico City, just a short walk from Tempi Mayor, you can fast orward to another century. It is here in the arched courtyard hallways of the Colegio de San Ildefonso that the Mexican mural movement. a unique style that catapulted a trio of Mexican artists to the front page of modern art, was born in 1922. The fiery political and mythic imagery created on these walls in the 1920s and 30s by Jose Clemente Orozco. Diego Rivera, and David Alfaro Siqueiros mirrored the country’s post-revolutionary ardor. These 20th-century murals are among Mexico’s finest artistic achievements. rivaling the art of preColumbian times.

Teotihuacan’s Pyramid of the Sun, the second largest pyramid in the Americas, is a glorious achievement of the Toltecs

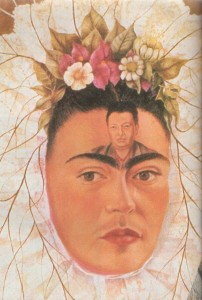

In these halls Rivera then 42 and not yet world famous. met his future wife. the teenaged and striking Frida Kahlo. Kahlo. considered Mexico’s greatest woman artist, is approaching cult status in the States, with collectors like Madonna bidding up the value of the artist’s paintings. (One of Kahlo’s surrealist styled self-portraits recently- fetched $1.4 million at a New York auction.)

Kahlo’s house in Coyoacan, a neighborhood in the south of the city, has been preserved and there you can see her last painting, Viva la Vida, as well as the Mayan urn that contains her ashes.

A menagerie of pinatas in Merida.

In a brand new museum, founded by Dolores Olmeda — once Riveras great patroness and reputed lover -a world-class collection of Rivera paintings and ephemera (including am enormous pair of the artist’s denim overalls) as well as the greatest concentration of Kahlo paintings anywhere. The museum — a gift to the country— is part of a recently restored 16th-century monastery, called La Noria, and is also the home of the collector-patroness. The Xochimilco section, where the museum is located, is the only neighborhood in Mexico City where you can take a gondola ride along flower-scented canals.

Daring young men: Indians performing an ancient ritual in honor of the Sun God.

In the rugged mountains that surround Oaxaca, a beautiful colonial city 315 miles southeast of Mexico City, are pure tonic. Many of oaxaca’s inhabitants bear the features and speak the unwritten languages of their Zapotec and Miztec Indian forbears. The architecture is uniformly low rise, colonial in style, and white stucco in color. No new building is allowed in the historic district. Best of all, car traffic is banned around the spacious tree-shaded zdcalo and charming bandstand of Plaza de Armas. The city is surrounded by craft villages that have their own individual folk art style —everything from weavings in Teotitlan del Valle to the green glaze pottery of Atzompa. In the city markets, everywhere you walk, black Coyotepec pots framed by ironworked windows, sit majestically on circular straw bases.

The polychromed and gilded interior of Oaxaca’s baroque church of Santo Domingo, five blocks north of the zdcalo, is a dazzling pastiche of 17th-century fantasy. The enormous illustrated relief of a genealogical tree over the entrance apse, said to represent the family of St. Dominick, branches wildly across the ceiling. Some six miles southwest of Oaxaca is Monte Alban, the ancient Zapotec hillside capital that flourished from 200 to 750 A.D. The Zapotecs were superb sculptors and their unique ceramic urns, as detailed in imagery as Greek vases, were their distinguished artistic contribution. They were also accomplished architects as evidenced by the plazas and temples of Monte Alban.

Zapotec ceramic funerary urn representing the “Goddess Thirteen Serpent” from the third or

fourth century.

It was the great Mexican archaeologist, Monte Alban. Caso discovered Tomb 7, a treasury of gold and silver ornaments, during a dig there in 1931. They reside safely at the museum. There is a statue of Caso at Monte Alban but the best sculptures are the ancient ones, 300 incised stone portraits of naked male danzantes Alfonso Caso, who extensively researched and excavated parts of (dancers) and nadadores (swimmers) set against the long wall of the Temple of the Danzantes at the southwest corner of the main plaza. Some of these mysterious figures sport bead necklaces, ear spools, and elaborate hairstyles. Only 5 percent of Monte Alban has been excavated. Each season, more of this stately site, carved out of a mountain tap, revealed.

Merida is the urban gate to the great Mayan city of the Yucatan Pennisula that prospered from the 9th to 1311k centuries. It is surprisingly cosmopolitain in a laid-back way, ideal for the entertaining of the international set aficionados aiming for the ancient stone stage sets at Uxmal, Kabah and Chichen Itza.

Merida’s most elegant boulevard, Paseo Montejo, is named after the 16th-century conqueror of the Maya. Horse-drawn calesas still cruise the boulevard past the impressive mansions built by the henequen (sisal) moguls at the turn of the century when Merida was called the “Paris of the West.” The Canton Palace houses the city’s highly regarded anthropology museum which contains some of the finest pieces excavated from Chichen Itza by the controversial 19th-century archaeologist, Auguste Le Plongeon. who reburied some of his ‘discoveries after losing favor from his sponsor.

It was General Francisco de Montejo the Younger who sacked the Mayan town of Tiho in 1542 and renamed it Merida because it reminded him—after his handiwork—of the Roman ruins outside of Merida in southern Spain. The Montejo Palace, built in 1549, and now a bank, is one of the few outstanding landmarks in the city. Its superb facade depicts, with a kind of brutal Renaissance machismo, two knights in armor standing on the naked

shoulders of vanquished Indians.

But another kind of victor, equally bloody, is evident throughout the grand ruins ofjungle-skirted Chichen Itzet where the Maya ruled 10 centuries ago. The reclining stone figure of the chac-mool, with the carved depression in his chest for holding the sacrificed hearts of captive warriors, presents a chilling view of that culture, one surrounded by sacred ceremony and sophisticated astronomy. Fabulously enriched by boat traffic plying the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean, Chichen Itza traded jade, orange pottery, obsidian, turquoise,

and gold.

The great pyramid, El Castillo, sits at the center of the site. The architectural majesty of this regal place survives at every turn. Even without its polychromed coat of blue, black, yellow, and ochre, the art at Chichen Itza dazzles. An epic series of stone relief narratives depicting battle and ritual scenes at the Temple of the Warriors convincingly links the visual art history of these now-anonymous artists to the Mexican masters of the 20th century.

In the green waters of the sacred Cenote at the north end of Chichen Itza (a large circular sinkhole and sacrificial pit from which important artifacts were dredged in the early part of this century), past and present meet head on. Just beyond this sacred site is a tiny airstrip, depositing wellheeled pilgrims from the resorts of Cozumel and Cancun.

Judd Tully is a New York—based writer specializing in cultural art. His articles

have appeared in the Washington Post, Architectural Digest and Art & Auction.