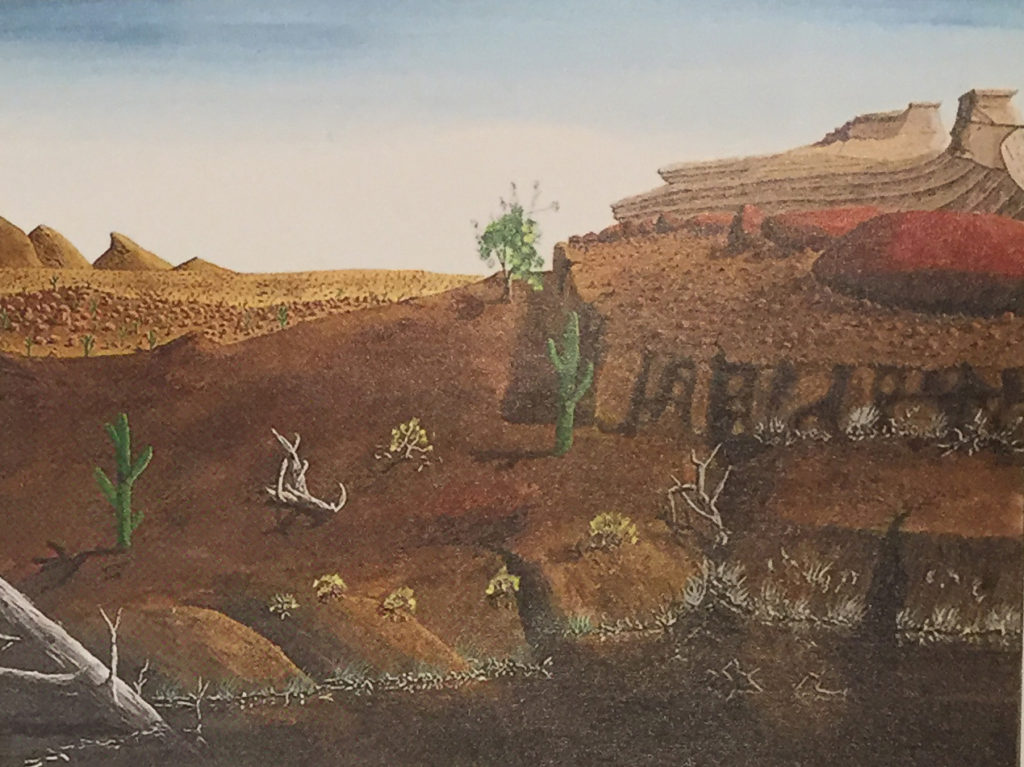

Peter Doige, “Peyote” (1976), 34 x 41 1/2 in, acrylic on muslin (courtesy Peter Bartlow Gallery)

Despite a favorable verdict, the odd scandal heightens art world concern that courts are not equipped to pass judgement on cases of authorship.

Grabbing headlines headlines, the trial of Robert Fletcher and Bartlow Gallery Ltd. v. Peter Marryat Doig in U.S. District Court in Chicago stumbled to a close in August after three years of litigation. Presiding Judge Gary Feinerman ruled, unencumbered by jury deliberation, that the plaintiffs’ claim of owning a genuine Peter Doig painting was invalid. As he stated, “Peter Doig could not have been the author of this work.”

The plaintiffs in the case, a former Canadian corrections officer and a Chicago-based art dealer with a 25 percent interest in the trial’s outcome, claimed the teenage Doig painted a Surrealist-style desert landscape some 40 years ago while serving time in a youth correctional facility in Canada, where Fletcher acquired the work from the artist for $100. The pair sought S7.9 million in damages from the artist.

Fletcher and Bartlow additionally claimed “unjustified interference” a a result of the artist’s threat to bring his own suit if the work in question was offered at auction under the name of Peter Doig. That claim was also rejected by Feinerman.

The case, which charitab minded, art-savvy onlookers view as a case of grossly mistaken identity, stemmed from the signature “Pete Doige 76” on the front of the landscape long owned by Fletcher. Over Doig’s adamant objection, the plaintiffs presented an authentication narrative, insisting the painting was really the juvenile work of the world-class artist, a single piece of whose authentic work has sold for more than $25 million at auction. Ten other works have each brought more than $10 million on the block.

“It was never a case of mistaken identity,” contends Gordon VeneKiasen, co-owner of Michael Werner Gallery and the artist’s dealer. “It was a scam and always was. It was a stickup job that shouldn’t have gone anywhere.”

The painting, given the title Peyote by plaintiff Bartlow, is an acrylic-on-canvas work measuring 34 by 41.5 inches and depicts a cactus-dotted desert landscape. It was painted in 1976. More recently, Bartlow offered the painting to Chicago auctioneer Leslie Hindman in 2012. The house declined to place the piece on the block after Doig’s gallery representative, Michael Werner Gallery, rejected its authentic status as a work by Peter Doig.

“This case was brought in bad faith,” says Matthew Dontzin, Doig’s attorney. “The plaintiffs lied to the court. They claimed they looked high and low for the person who signed the painting ‘Pete Doige’ with an “e”, and there was no one in Canada who fit the description. It was completely untrue, and it didn’t take me long to find the real painter, who died in 2012.” Additionally, “they went so far as to try to extort Peter Doig’s 80-year-old father, the artist, and the gallery for a settlement,” says Dontzin.

“That is absolutely a lie,” Bartlow responded when told of the attorney’s remark. “And if those comments are published, we will file a defamation suit against him. What I said to his father, we were asking for some kind of information and to this date has not produced any.”

“The factual evidence was so clear [the piece] was not by the Doig we know, the famous one,” says attorney and art adviser Ralph Lerner. “I’m amazed it went to trial.” In a lighter vein, he added, “Judges tend to love these art cases because everything else they do is so boring.”

Less humorously, the cost to Doig of defending his name and reputation was, no doubt, a small fortune. The artist retained blue-chip New York litigator Dontzin, who famously represented super-dealer Larry Gagosian and hedge-funder Dan Loch in various matters. Add to that the public cost of underwriting a seven-day court trial in a major city.

“It’s a shame Doig had to be put through this,” says attorney and Art+Auction contributing editor Thomas Danziger. “The plaintiff was barking up the wrong tree.” He continued,”I’ve never seen a case in which a court has compelled either an authentication committee, an expert, or an artist to authenticate a work of art.”

“These are rare cases, but they happen from time to time,” says attorney Ronald Spencer, who served the shuttered Andy Warhol Art Authentication Board and the disbanded Jackson Pollock Catalogue Raisonne Committee.

Both Lerner and Spencer mentioned a somewhat related case, the only one they could recall involving a living artist, which concerned the authenticity of a Balthus drawing, Colette in Profile,1954. The artist rejected the work as his own, writing “faux manifeste” (“obvious fake”) on the back of it. But in a 1995 decision, a New York appellate court deemed it to be an authentic Balthus.Unlike Doig, Balthus did not testify at or attend the New York trial over the drawing, which Gallery Gertrude Stein, the defendant, sold to collector and dealer (and plaintiff) Arnold Herstand, who subsequently sold it to Paris dealer Claude Bernard for $51,000.

The drawing had been a gift to the artist’s former lover, and Balthus’s denial ofauthorship appeared to be one of animus or revenge against her. The court stated, “An artist’s repudiation of his own creation is not sufficient in and of itself, to establish that work of art is fake.”

If Doig had been sued with the same allegations over a later work, say, from 1990 onward, the artist or his lawyer could have invoked the 1990 Visual Artist Rights Act (VARA), which gives artists the rights of attribution andintegrity, including “… to prevent the use of his or her name as the author of any work of visual art which he or she did not create.” It also provides the right “to prevent the use of his or her name as the author of the work of visual art in the event of a distortion, mutilation, or other modifications of the work, which would be prejudicial to his or her honor or reputation.”

Artist Cady Noland used this provision to protest and reject the sale of a $1.4 million work, Log Cabin Blank with Screw Eyes and Cafe Door, 1990, which sparked a 2015 lawsuit. Noland had previously blocked the 2012 sale by Sotheby’s of her Cowboys Milking, 1990, a silkscreen she deemed to be too damaged to continue to be trafficked through the market. The artist was subsequently sued by the latter work’s consignor, New York-based dealer Marc Jancou.

The central issue in such cases is the artist’s word regarding the authorship of a work that he knows he did not create or seeks to disown as a result of irrevocable change to the original object by another hand. “What the court said and what the art market says are two entirely different things,” contends Danziger. “You could have a judge rule that it’s a Peter Doig all day long, but because the artist has disavowed this as his own work, I would say it has no market value. Auction houses and would-be buyers couldn’t care less about what a judge in a case like this has to say and are interested only in what the artist has to say.”

In a statement released by Michael Werner Gallery, the artist said, in part, the “verdict is the long overdue vindication of what I have said from the beginning four years ago: a young talented artist named Pete Edward Doige painted this work, I did not…. Thankfully, justice pre-vailed but it was way too long coming…. That a living artist has to defend the authorship of his own work should never have come to pass.”

“To question whether a [living] artist actually made a painting is extraordinary,”

says Francis Outred, European head of postwar and contemporary art at Christie’s, who oversaw the house’s sale of Doig’s Gasthof, 2002-04, for 69.9 million ($17 million) in London in 2014.”It is an outrage that one of our most important living artists has been put through this. At a time when he’s in a great creative moment, he has to put time, energy. and money into this ridiculous case.”

An art appraiser testified for the plaintiffs that the painting would be worth $6 million to $8 million if blessed by Doig, but Outred disagreed. “Even if it were a Doig from 1976, when he was about 16 years old,” he said, “it wouldn’t have been worth more than 610,000 to 615,000 ($13-20,000) anyway.”

What will become of the spurned painting, now relegated to the status of a work by the late artist and former inmate Pete Doige, is an open question. It remains on Bartlow’s website attributed to”Peter Doig (or Doige?), “the parenthetical being added after Dontzin sent a cease-and-desist letter to the plaintiff’s attorney.

Asked what comes next in the Doig saga, Bartlow says,”Every avenue is being explored and are being considered, including

story rights and purchase offers. At this point, we don’t think we know truth yet, and the court case just raised more questions.”

William Zieske, the plaintiffs’ attorney, added, “It’s a court verdict and judgment, but it’s not the end of the story. There will always be a question of whether this decision will be correct or not.” At press time, it remained unclear whether Bartlow and Fletcher will appeal the verdict. “You know what?” queried Outred of Christie’s about the 1976 work.”It’s quite a good painting.