Captain John Murphy, gate keeper, photo: Gayle Gleason

Sailors’ Snug Harbor, the multifaceted white elephant created by a privateers’ fortune in the 18th century, is leaving, a landmark Greek Revival home on Staten Island’s Kill Van Kull for more salubrious shores in Sealevel, North Carolina. After 10 years .of cantankerous mutterings petitions, complaints to the New York Attorney General’s office and angry letters to the editor charging that they were being exiled to a hurricane and mosquito-infested nomansland called Sealevel. the 120 ancient mariners will quietly move out in late June by bus and plane to their new $6.000.000 shelter in North Carolina.

175 years ago the Harbor’s founder, Captain Robert Richard Randall, a-bachelor heir to his father’s acumen for plundering English merchant ships and penchant for philanthropy with his attorneys, Alexander Hamilton and Daniel D. Tompkins, drew up an ironclad will that established an asylum or mariner hospital for “maintaining and supporting aged, decrepit and worn-Out sailors.” Randall’s country estate. known in 1801 as the Minto Farm, was to provide the “rents. issues and profits” for building and maintaining the asylum.

A 30-year court battle ensued, allowing time for Randall’s holdings to ripen while taking disgruntled nephews and cousins of Randall to the U.S. Supreme Court. Hamilton’s blueprint for a snug harbor prevailed. Randall’s trustees were free to pursue their testator’s wishes. The Trustees of Sailors’ Snug Harbor incorporated in the state of New York and received the legislature’s permission to purchase Isaac B Houseman’s 130-acre farm on the north shore of Staten Island to build a mariner’s home and to lease the increasingly valuable Manhattan property to insure adequate income to support the asylum.

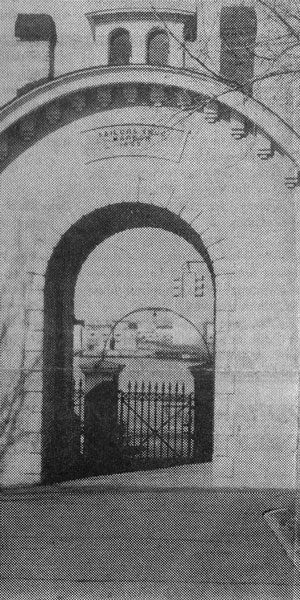

Entrance, Kill van Kull, Staten Island, photo: Gayle Gleason

Randall’s will designed Snug Harbor to be run in perpetuity and assigned that responsibility to an automatically self-perpetuating board of trustees who mirrored New York City’s establishment in 1800. They included the senior ministers from Trinity Church and The First Presbyterian Church. the Mayor of New York City. the president of the Chamber of Commerce and the top two officers of the Marine Society (a charity for indigent sea captains. their widows and orphans). Randall’s father, Thomas, founded the Marine Society and was one of the original 12 members of the N.Y. Chamber of Commerce. Two other municipal and state offices have since been abolished.

On August 1, 1833. the Harbor opened its eight-columned portico to 37 wizened sailors and the “haven for sailors home from the sea” began to flourish.

As the development of Manhattan island sped north. Minto’s 21 acres (assessed in 1801 at $12,500) were transformed into Washington Square North. 10 square blocks bordered by Fifth Avenue to the west, 10th Street to the north and Fourth Avenue to the east.

By 1848 rental income front the Manhattan property generated $40,000 a year. Elegant row houses were built along Washington Square North under the conservative guidance of the trustees. Captain Randall’s remains were transferred for a second time (the first in 1825 when his grave would have blocked the opening of 8th St.) from nearby St. Marks on the Bowery Church by steamboat to dockside at the Staten Island site. A $10,000 commission to sculpt an heroic statue in bronze of the founder was awarded to Augustus St. Gaudens.

Building on the grounds of Sailors’ Snug Harbor Was helter skelter. By 1880 a remarkable hodge -podge of graceful temple-like Greek Revival dormitories fronting the Kill in New Brighton were coupled with ramshackle Victorian cottages for Harbor employees, a stunning Anglo-Italianate Chapel and mixed Gothic utility laundry and morgue facilities. A massive wrought iron fence completed in 1876 stood sentinel to this magnificent montage of architectural styles.

The first sign of skullduggery at the harbor occurred in 1872 when the institution’s governor. Thomas Melville (Herman’s younger brother), was accused by an employee of. embezzling funds. Melville kept his job, but a bursar’s office was set up in Manhattan to handle all purchases. Relations between Tom and his brother soured and Herman retreated to his mundane clerical duties (later described in “Bartleby the

Scrivener”) as an assistant customs inspector in Manhattan.

By 1898 income from ground leases and mercantile building ren-tals in Manhattan had soared to $400,000 a year. Up to The -Depression the Harbor was re-garded as the nation’s richest charitable trust. In 1910 the median age of the “Snugs” was 45 and the Staten Island institution had a self-sufficient dairy and poultry farm and large vegetable gardens. Electric power was produced independently. The rank of “Snugs” who picked up the honorary title of “Captain” after entering the Harbor swelled to more than 900 men.

For a worn-out mariner the alternatives to Harbor life were bleak. Without union pensions and social security many old salts wound up as derelicts on the Bowery shaking away to the toe of “old Joe” (Syphillis).

Compared to the Captains of the 1930’s, today’s “snugs” are buoyed by substantial Maritime union pensions and Medicaid. The age of mariners entering the Harbor has steadily climbed in the median age at the hornet ow 77 Medical care costs for the aged Snugs, has correspondingly soared. The ranks of deceased Snug, 7,000 strong are buried pell-mell and without the grace of tombstones a half mile behind the Harbor on Monkey Hill.

The Great Depression bushwhacked the Trust and tore the bottom out of their golden real estate egg in Greenwich Village. Buildings were abandoned in droves and property values sank. The trustees entered into long-term, low-return ground rental leases and effectively froze their major source of revenue. Their halcyon days crashed to a halt and by the early 1950’s the Board decided to snug up. Sailors’ Snug Harbor entered Hard Times.

Determined to cut escalating operating expenses, the trustees winnowed the influx of Harbor applicants and tore down half the 40-odd buildings on the Staten Island site. The most exotic casualty was a 1116 scale replica of London’s St. Paul’s Cathedral designed by R.W. Gibson. Attempts were made by the trustees to charge the Snugs a percentage of their pension payments to cover mounting medical costs. Complaints multiplied and the National Maritime Union (NMU) and the In- ternational Seafarers Union filed charges with the Charitable Foundation’s Bureau of the New York State Attorney General’s office (AG). A paroxysm of litigation loomed.

In December 1965. The Board of Estimate approved the Landmark Preservation Commission’s designation of landmark status to Snug Harbor. Seven years later. in March of 1972, Snug Harbor was listed on The National Register of Historic Places. The trustees took the new Landmarks Preservation Law to court. The Harbor charged an unconstitutional denial of the owners’ right to deal with his property as he saw fit. It alleged the landmark designation placed an improper burden on the charity. The trustees wanted permission to tear down their “landmark” buildings and erect a more efficient plant.

The Harbor won the initial round in the Nov York Supreme Court but was overturned by the Appellate Division in an unanimous, decision. The institution on Staten Island was cited for hospital code violations (no elevator and lack of fireproofing) by the State Department of Health. Inflation continued to spiral costs of maintaining the men ($8,000 per Snug a year in 1973 compared to toughly 5600 per man in 1940) and yearly accounting reports submitted by the trustees indicated an ever-increasing operating deficit ($255,000 in 1970). This occurred despite the skyrocketing increase of the trust’s rental income from $4,000 in 1800 to about $1,270,900 in. 1974. The Charitable Foundations Bureau of the AG entered the picture with a suit charging the trustees with waste and mismanagement.

Economics obscured the courtroom tug of war under the guise of a high stakes monopoly game. The president of the Board of Trustees, Wilbur E. Dow. Jr.. an admiralty lawyer and president of the Marine society. came up with an alternative site for relocation of the Snugs in the Cape Hatteras area of North Carolina. Daniel E. Taylor of the West Indies Fruit Company. an old client of Dow’s. offered the trustees 100 acres of coastal land in an undeveloped area called Sealevel for 5200 an acre.

The site was adjacent to a half-empty general hospital run by Duke University. The -climate seemed ideal for the aging mariners and the trustees felt it advantageous to move he Snugs. from New York. A petition was filed in early 1971 with Surrogate S. Samuel Difalco to sell the Staten Island property and, resettle the Snugs in Sealevel. Permission was granted despite the AG’s effort to force the issue into the State legislature where Randall’s trust was first incorporated. The trust is currently run by,only half of its designated officers. dominated by the Marine Society and Trinity and First Presbyterian Church. The Mayor’s and Chamber of Commerce president’s participation has long since atrophied from the trustee’s monthly meetings.

Sigmund Sommer president of Sigmund Sommer Construction Co. Inc.. ESSCO. Garmaret Realty, Sorel Realty. Moffat Realty and landlord of 43 primp prewar Manhattan apartment buildings. purchased 66 coed of the Staten Island property for $6,235,000 in January 1972. On September 22. 1972. the City of New York under the administration of Mayor John V. Lindsay purchased the remaining 14:5 acres, which included .the row of five landmark buildings. for $1,870,000. The city nudged by Staten Island’s political and cultural establishment. Was eager to move the cramped Staten Island Institute of Arts & Sciences into the Greek Revival buildings and provide more park land for the city’s only growing borough.

Sommer planned to build a medium-rise 2,800 luxury apartment complex on the land but was stymied by community opposition. About 23 months after Sommer’s purchase of the 66 acres from the Harbor the City (blushing at the expensive two-year delay) bought the parcel from Sommer’s Sorel Realty for $7,845,000. Sommer netted a $1.610,000 profit.

Reverend Dr. John 0. Mellin of the Firm Presbyterian Church on West 12th Street, current president of the Board of Trustees and ‘longest reigning board member (27 years) in recent Harbor history. said. “We’d go out of business if we stayed here. Even by the time we snugged up and modernized. inflation had eaten up the third we had saved. Real estate is like a poker game and you have to he willing to take chances. We’re not bankrupt, continued Mellin. “the city is. We got out, we’re free from them at last and now they’re in trouble.”

Captain Randall’s Manhattan estate produced $892,566 in ground rentals and $378,315 in building rentals in 1974. The trustees. have permission from the Surrogate Court to sell the Manhattan property off as leases expire, a provision expressly forbidden in the original will. Both Captain Randall and General Hamilton (who helped the captain return his father’s profits to the sea where they originated) would do pirouettes in their respective graves if they were privy to the Surrogate’s actions.