Collectors’ Reversals of Fortune Can Mean a Payday for Auction Houses—or Spell Disaster

Forced sales of fine art resulting from debt have juiced auction rooms going back to Georgian England times, and with the Covid-19 pandemic still raging and auction sales halved from the same period last year, we may soon be seeing more cases—not of the virus but of financial maneuvering.

So far, the only major cache of works from a single high-profile seller to come to market during the pandemic has been from billionaire Ronald Perelman. He sold two major paintings in a Sotheby’s online auction in July: a Miró that fetched $28.6 million and a Matisse that went for $8.3 million. Over the summer, before ARTnews went to press, Bloomberg revealed that Perelman would sell another high-level tranche of 20th- and 21st-century works culled from his 1,000-piece-strong collection through Sotheby’s in the coming months in both public and private sales. All that’s known about the Perelman offerings comes from what John Vlasto, a spokesman for the MacAndrews & Forbes holding company, where Perelman is CEO, told Bloomberg: “Due to changes in the world both socially and economically, we have decided to reset MacAndrews & Forbes in a manner that will give us maximum flexibility both financially and personally.”

The financial moves chronicled below are far from workaday portfolio adjustments. There have been sales held at the behest of the Internal Revenue Service and sordid circumstances that run to embezzlement and even attempted murder. And then there are the rogues who stiff the auction houses, whether through unpaid loans or falling through on winning bids when the bill comes due.

Behold, the most precipitous falls of the past 50 years.

Claude Monet, Iris jaunes au nuage rose, 1924–25, once owned by Josef Rosensaft.

Show Me the Monet

Josef Rosensaft.

A particularly rich period for these so-called forced sales jump-started in the mid-1970s and took off to greater heights in the ’80s and ’90s, when fallen private collectors and corporate entities sought financial relief in the salesrooms. The beginning of that cavalcade of highly publicized sales can be traced back to the single-owner sale of the collection of the late Josef Rosensaft, Holocaust survivor and storied philanthropist, at Sotheby Parke Bernet in 1976.

The top lot in the Rosensaft sale was Paul Gauguin’s 1889 painting Still Life with Japanese Woodcut, which sold to the Shah of Iran—who bid on the telephone through his court chamberlain—for a record $1.4 million. (The painting currently resides in the Tehran Museum of Art.) A Claude Monet, Iris jaunes au nuage rose from 1924–25, sold for $130,000 and a Kees van Dongen, Trinidad Fernandez from 1907, hit a record $160,000.

Rosensaft left behind a mountain of debt, with liens on his holdings by eight financial companies. His heirs received none of the $5.6 million auction haul.

“Nobody knows quite what happened to Rosensaft,” said dealer David Nash of Mitchell-Innes & Nash, who was director of fine arts for Sotheby’s Impressionist and Modern department when the sale took place. “He was a gambler and a very successful businessman. He made a lot of money and bought a lot of paintings and then suddenly, everything had to sell. I think it was because of gambling debts.”

Vincent van Gogh, Irises, 1989, once owned by Alan Bond.

COURTESY J. PAUL GETTY MUSEUM, LOS ANGELES.

The Name’s Bond. Alan Bond.

Alan Bond.

AP PHOTO/RICK RYCROFT.

The debt calculator needle jumped again after the “record” $53.9 million sale of Vincent van Gogh’s Irises at Sotheby’s in November 1987 to Australian brewing, media, and property magnate and America’s Cup winner Alan Bond, when it turned out Bond couldn’t pay for the picture.

In a secret post-sale deal, Sotheby’s advanced Bond half the purchase price through the firm’s financial services arm, but that didn’t help either: Bond didn’t pay his share, so Sotheby’s sent scouts to Perth to retrieve the painting.

Ultimately, Bond went to prison down under for using company funds to buy art for his personal collection, and Sotheby’s brokered a private deal in 1990 with the J. Paul Getty Museum to purchase the in-hock painting for an undisclosed sum. “They certainly didn’t pay the headline price,” said Jennings. In fact, the Getty put up some lesser-valued works to sell discreetly at Sotheby’s as a way to fund part of its storied purchase.

In the early ’90s the art market entered a deep recession. Nash says that, according to his recollection, “the Getty gave us part cash and part some pictures to sell when it was really a tough time to sell pictures.”

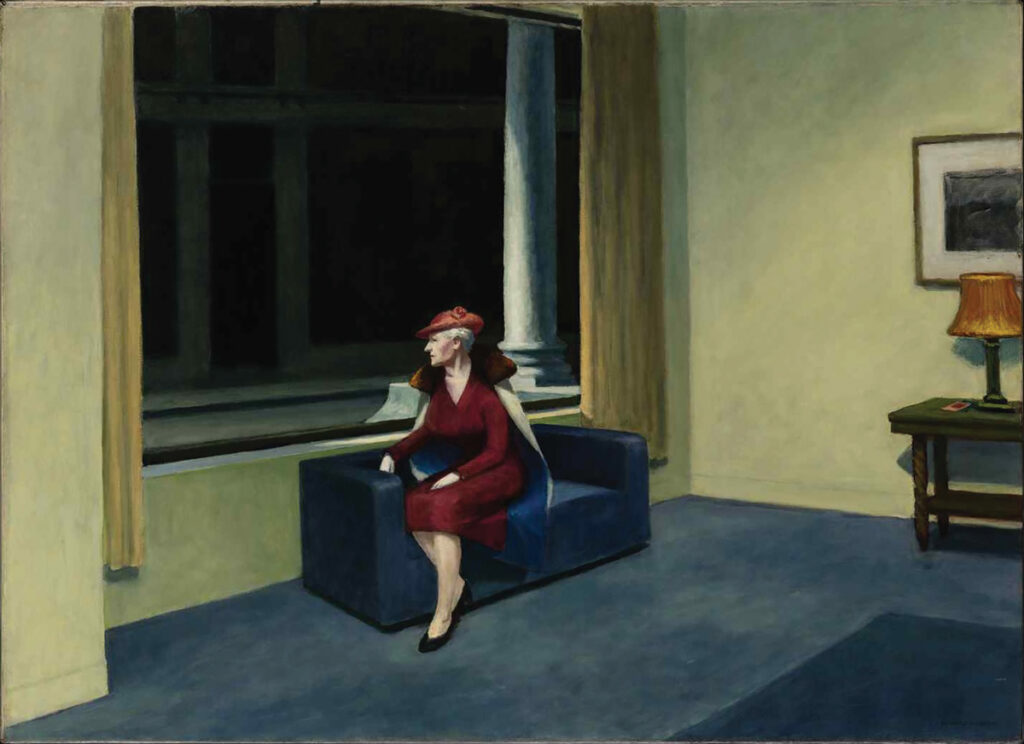

Edward Hopper, Hotel Window, 1955, once owned by Andrew Crispo.

COURTESY SOTHEBY’S. © 2020 HEIRS OF JOSEPHINE N. HOPPER/ARTISTS RIGHTS SOCIETY (ARS), NEW YORK

Death and Taxes

Andrew Crispo.

AP PHOTO/DAVID BOOKSTAVER.

In December 1987, on the heels of Bond’s flawed purchase of Irises, Sotheby’s held a blockbuster sale of 69 lots of American art. The title in the catalogue read: “Property from the Andrew Crispo Gallery, Inc. collection, sold in cooperation with the Internal Revenue Service and Rosenthal & Rosenthal” (a New York–based factoring company).

Crispo was serving a seven-year prison sentence for income tax evasion, owing the IRS millions of dollars. In 1985, his deluxe gallery in the art-filled Fuller Building on East 57th Street had become linked to the tabloid-coined “Death Mask Murder” of a young male model when the rifle used to kill him was found there. The scandal eventually led to the conviction of Crispo’s gallery assistant Bernard LeGeros.

In the end, the Crispo provenance, sullied by tabloid headlines, didn’t hurt the sale’s outcome. The auction set records, including the cover lot, Edward Hopper’s 1927 Captain Upton’s House, that sold to actor Steve Martin for $2.3 million. Another work by Hopper, Hotel Window, from 1956, went to Malcolm Forbes for $1.3 million.

Recalling Crispo, David Norman, at the time a young Impressionist and Modern specialist at Sotheby’s and currently chairman, Americas at Phillips, said, “He had such beautiful taste. And so soft-spoken and kind of elegant in the way he presented himself. We used to get calls from him in prison about the next consignment.”

A gilt-bronze rhinoceros musical table clock, ca. 1750, similar to the one sold by Roberto Polo.

COURTESY SOTHEBY’S

The Cuban Gatsby

Roberto Polo.

SABINE GLAUBITZ/PICTURE-ALLIANCE/DPA/AP IMAGES

The following year, Sotheby’s held the first of a series of sales at the behest of the Internal Revenue Service to satisfy the outcome of a significant swindle exceeding $110 million by the Private Asset Management Group, owned by one Roberto Polo—who would shortly become an international fugitive.

Polo, a collector-dealer and financier who was known as the “Cuban Gatsby,” had deep holdings of French and Continental furniture and decorations. Of the decorative treasures in the first Polo sale at Sotheby’s New York, a Louis XV ormolu and patinated-bronze musical clock from the mid-18th century sold for $660,000, and a console in two-tone giltwood from the Palais de Fontainebleau, dating from the late 18th century, made the top lot at $1.3 million. The sale totaled $9.8 million, a record at the time for a single-owner sale in its category.

Polo eventually served out a prison sentence, and recently opened two eponymous museums in Cuenca and Toledo, Spain, that feature thousands of works from his now unencumbered collection. “It’s hard to think of anyone tainting their provenance unless it was a Nazi or something,” said a former Sotheby’s specialist. “People will still buy a painting or a decorative work of art even though a shitty person owned it and is reselling it.”

An early George III kingwood and rosewood commode, ca. 1765, similar to the one sold by Claus von Bülow.

Reversal of Fortune

Claus von Bülow

Despite the tawdry circumstances surrounding their sell-offs, Sotheby’s and the sellers didn’t shy away from revealing Crispo and Polo’s identities. Not so the two-session, single-owner sale at Sotheby’s in October 1988, the catalogue for which said merely “Property from a Private Collection.” The artwork reproduced on the cover, however, was a dead giveaway: a painting by artist Felix Kelly of Clarendon Court, the 12,000-square-foot Newport, Rhode Island, mansion owned by Claus von Bülow and his wife, heiress Martha Sharp “Sunny” von Bülow.

Martha had languished in a coma resulting from an insulin overdose; her husband was tried twice and ultimately acquitted for attempted murder. (The 1990 Hollywood film Reversal of Fortune, starring Jeremy Irons and Glenn Close, tracked the couple’s lavish lifestyle and von Bülow’s courtroom dramas.) The seller was Claus’s family, and the contents of the $11.5 million sale included English furniture, paintings, and silver accumulated over 20 years.

Some of the highlights included a George III ormolu-mounted rosewood commode by Pierre Langlois that made $880,000 and a pair of George IV silver soup tureens, covers, liners, and stands by master silversmith Paul Storr from 1822 that sold for $924,000.

“What tends to happen, even when there’s no public announcement of ‘property of so-and-so,’ the professionals know what’s going on by the time the auction takes place,” said Jennings. “It’s a matter of detective work and you can usually work it out if it’s a distress sale or a forced sale.”

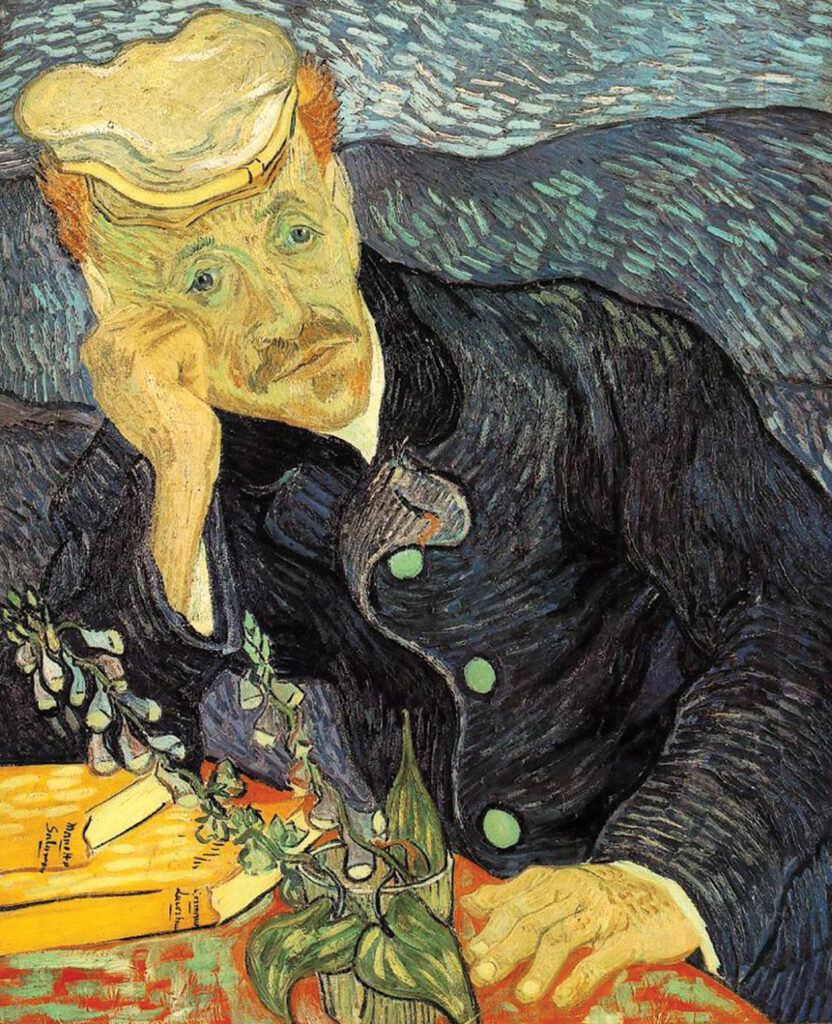

Vincent van Gogh, Portrait of Dr. Gachet, 1890, once owned by Ryoei Saito

Paper Trail to a Broken Dream

Ryoei Saito.

AP PHOTO/KYODO NEWS

So-called bad-debt art, a term coined in the early ’90s when the Japanese went deep into debt to purchase a huge volume of Western art, doesn’t always head back to the auction rooms. Evidence for this is the dramatic fall of Japanese paper magnate Ryoei Saito, who bought two masterpieces in a 24-hour period at Sotheby’s and Christie’s in May 1990: Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s Bal du Moulin de la Galette for a record $78.1 million, and Vincent van Gogh’s Portrait of Dr. Gachet for a record $82.5 million. By 1991, Saito’s Daishowa paper empire in Fuji City had collapsed in a tsunami of debt and the paintings were seized by Fuji Bank, one of his creditors.

Both of Saito’s pictures eventually sold privately, with the Renoir going to an otherwise anonymous European collection and the van Gogh to the Austrian banker and hedge fund manager Wolfgang Flöttl, an astute collector and investor who quickly became a major art-buying player with seemingly unlimited funds and exquisite taste. Flöttl was a society bigwig in New York, married to interior designer Anne Eisenhower, the granddaughter of President Dwight D. Eisenhower.

“I think it was Dede Brooks [Diana D. Brooks, then CEO of Sotheby’s, who was later fired and indicted on price-fixing charges for colluding with Christie’s] who arranged the sale from Saito to Flöttl,” said Nash. “Then Flöttl had to sell it because he borrowed all this money from Sotheby’s and I think that’s when Sotheby’s resold it.”

Flöttl’s buying and selling thread is a long one. At the top of his game in the fall of 1997, riding high with a $240 million loan from Sotheby’s, he bought Pablo Picasso’s 1932 Le Rêve at Christie’s from the Victor and Sally Ganz single-owner collection for a then record $48.4 million. That was before allegations of engineering a $1.4 billion scam with his hedge fund went public.

Less than two years later, Nash said, Flöttl “had to start divesting his paintings and [my wife, dealer] Lucy [Mitchell-Innes] and I sold a lot of paintings for him privately. We sold the Picasso to Steve Wynn for about $60 million, so Flöttl made quite a handsome profit on that painting.”

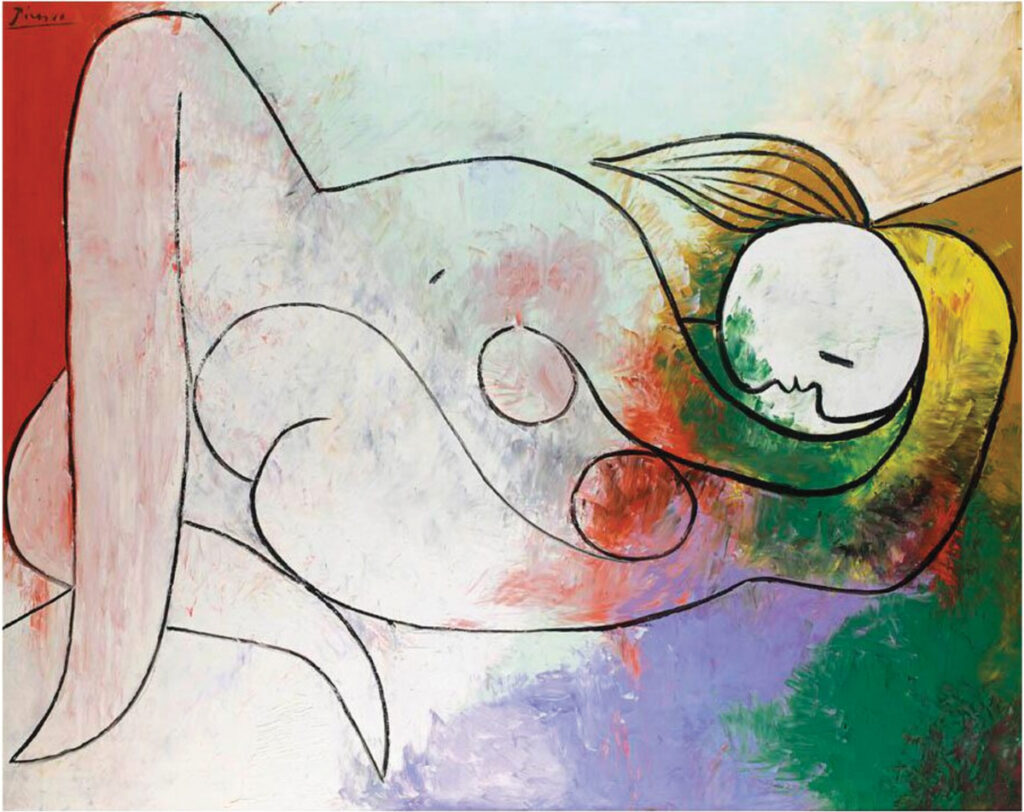

Pablo Picasso, Femme couchée à la mèche blonde, 1932, once owned by Meshulam Riklis.

©2020 ESTATE OF PABLO PICASSO/ARTISTS RIGHTS SOCIETY (ARS), NEW YORK.

Nightmare on Wall Street

Meshulam Riklis

Compared to the high drama of IRS seizures and criminal court proceedings, some reversals of fortune seem run of the mill; nevertheless, they serve to feed the art market, as evidenced by the single-owner sale, held at Christie’s New York in May 1994, from the personal collection of Turkish-born, Israeli-raised corporate raider Meshulam Riklis (1923–2019), property from the collection of the McCrory Corporation, a distressed company that he ran.

Riklis, a storied leveraged-buyout magnate whose master’s thesis was on the “effective non-use of cash” and whom financial columnist Allan Sloan dubbed “Freddy Krueger, the Bond Holder’s Nightmare on Wall Street,” was also a tabloid favorite due to his marriage to actress Pia Zadora when he was 53 and she was 24.

Riklis’s collection was first-rate and distinctively Modern, from Egon Schiele and Fernand Léger to Piet Mondrian and Amedeo Modigliani. Unluckily for Riklis and Christie’s, it was a bad night for the market. A whopping 50 percent of the offerings from the various owners’ portion of the auction went unsold, as did eight of the 15 Riklis lots.

One of the few successes was Picasso’s ravishing 1932 Marie-Thérèse Walter–period painting Femme couchée à la mèche blonde, which sold for $4.6 million to an anonymous telephone bidder. (As it happens, the painting came back to market at Sotheby’s London in June 2004, when it sold for $9.3 million.)

In any case, it seemed like quite a fall for the retail tycoon who in 1984 gave 249 works of abstract art from his corporate collection at McCrory to the Museum of Modern Art, along with $1.75 million for the museum’s capital campaign fund.

You can still buy the Christie’s Riklis catalogue for $4.99 on Amazon or $6.99 on eBay and wonder at the bargains.

Cindy Sherman, Untitled #261, 1992, once owned by Bernardo Nadal-Ginard.

COURTESY METRO PICTURES, NEW YORK

Doctoring the Books

Bernardo Nadal-Ginard

Another catalogue still available from used-book websites is that for a trove of cutting-edge contemporary pieces put up by Sotheby’s New York in May 1997: works from the collection of Boston Children’s Heart Foundation, Children’s Hospital, a property title that may evoke warm and fuzzy sentiments.

But the owner of those works was cardiologist Bernardo Nadal-Ginard, who was imprisoned for embezzling millions from the charity he ran to buy art for his personal collection and was ordered to pay $6 million in civil fines.

Nadal-Ginard’s prescient holdings—more than 100 works from over 90 artists, ranging from Matthew Barney and Robert Gober to Jeff Koons and Cindy Sherman—sold for a then whopping $4.3 million, well before their rising markets matured.

Barney’s Transexualis (Decline) from 1991 fetched a record $343,500 (est. $100,000–$150,000); Jeff Koons’s Stacked, a pile of polychromed wood animals from 1988, made a record $250,000 (est. $125,000–$175,000); and Robert Gober’s stunning untitled wax sculpture of a human trunk upside-down sold to dealer Iwan Wirth for $189,500 (est. $125,000–$175,000).

Ed Ruscha, Angry Because It’s a Plaster, Not Milk, 1965, once owned by Halsey Minor.

©ED RUSCHA/COURTESY GAGOSIAN

Low Tech

Halsey Minor.

SHANNON MINOR

The pace of distressed or forced sales has slowed a bit in the 2000s, although the headline dramas around it have hardly abated. “The Collection of Halsey Minor” at Phillips de Pury & Company in May 2010 brought $21 million for the 19 lots sold, including Richard Prince’s Nurse in Hollywood #4 from 2004 that made $6,466,500 and Ed Ruscha’s Angry Because It’s a Plaster, Not Milk from 1965, now in the Broad Collection, that brought $3.2 million.

Minor, a storied digital tech entrepreneur and founder of CNET, which CBS later bought for $1.8 billion, had a collecting mantra according to Phillips, “it is my mission to collect only the best.”

But he fell into trouble along that pricey way by being heavily overextended as the financial panic of fall 2008 struck. He was ultimately ordered by the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York to pay off a $21.6 million delinquent loan to an affiliate of Merrill Lynch.

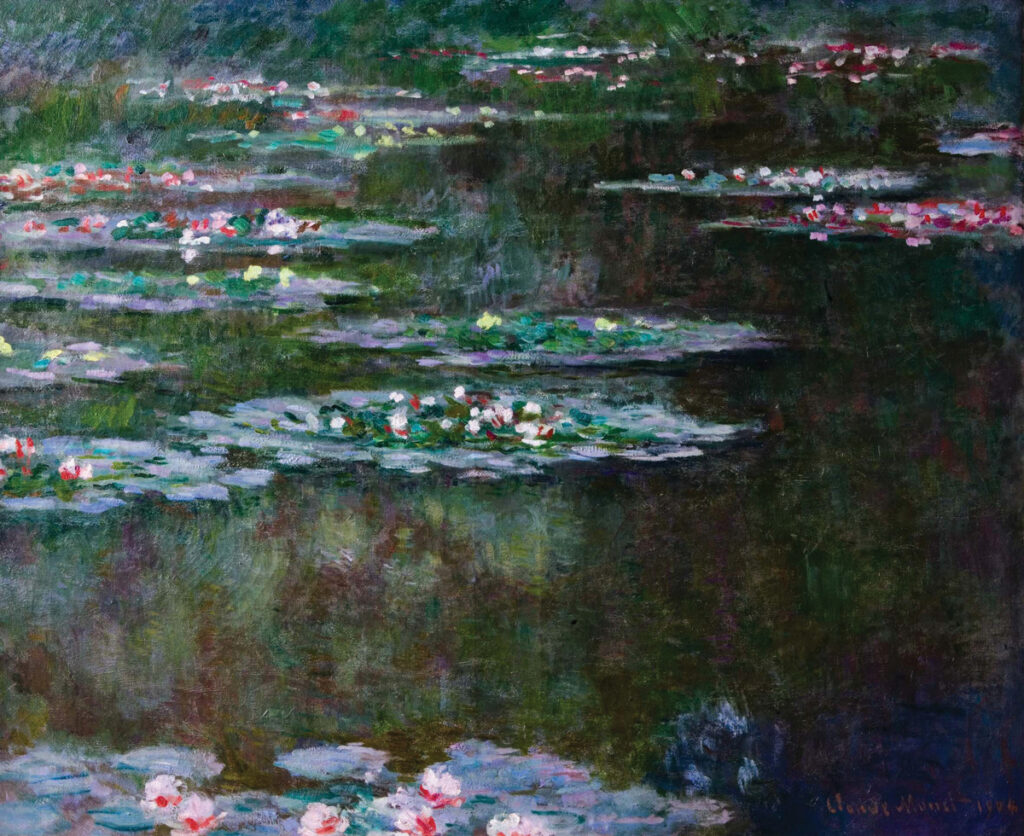

Claude Monet, Nymphéas, 1906, once owned by Jho Low.

COURTESY SOTHEBY’S

Smooth Criminal

Jho Low.

STUART RAMSON/INVISION FOR THE UNITED NATIONS FOUNDATION/AP IMAGES

But this was small change compared to the runaway exploits of Malaysian financier and current fugitive Jho Low, who bought prodigiously at auction in almost breathless fashion, acquiring Jean-Michel Basquiat’s Dustheads (1982) at Christie’s New York in May 2013 for a record $43.5 million, Pablo Picasso’s Tête de Femme from Sotheby’s New York in November 2013 for $39.9 million, and Claude Monet’s Nymphéas (1906) at Sotheby’s London in June 2014 for the equivalent of $53.9 million.

“It was so bizarre,” said a former Sotheby’s business getter who took the winning bid from Low over the telephone for the Monet Nymphéas, “he’d come in (Sotheby’s) with Leonardo de Caprio, and his posse, but he was this pudgy, unremarkable fellow, but remarkable in a criminal way. He was trying to be cool.”

Low was forced to sell some of his overpriced bounty due in part to an unpaid $100 million loan from Sotheby’s, and the results weren’t pretty. The Basquiat reportedly sold in 2016 in a private sale brokered by Sotheby’s, just as the FBI was investigating Low’s finances in the U.S. and abroad, for $35 million to hedge fund manager Daniel Sundheim, a 28 percent haircut; and the Picasso went for the price of $27.4 million when it reappeared at Sotheby’s London in February 2016, representing a whopping 31 percent shave. The fate and exact whereabouts of the Monet remain a mystery, at least for now.

“The nature of the problems associated with the client can impact how people feel about values,” said Phillips CEO Edward Dolman. “You take the case of Jho Low—he did a huge amount of business in the market for awhile and bought great quality material but it was definitely understood he was using funny money.”